8.3 Barriers to Workplace Advancement

Many obstacles still exist when it comes to achieving gender equality in the workplace. Sometimes these barriers have been institutional, such as legally restricting women’s participation in military combat roles. Sometimes, people’s prejudices prevent equal gender participation in the workplace. There were times, such as in the early 1900s, when women were thought to be so delicate they could not understand complex scientific work such as chemistry and physics. People believed that thinking hard about complex situations or work-related stress would physically harm women.

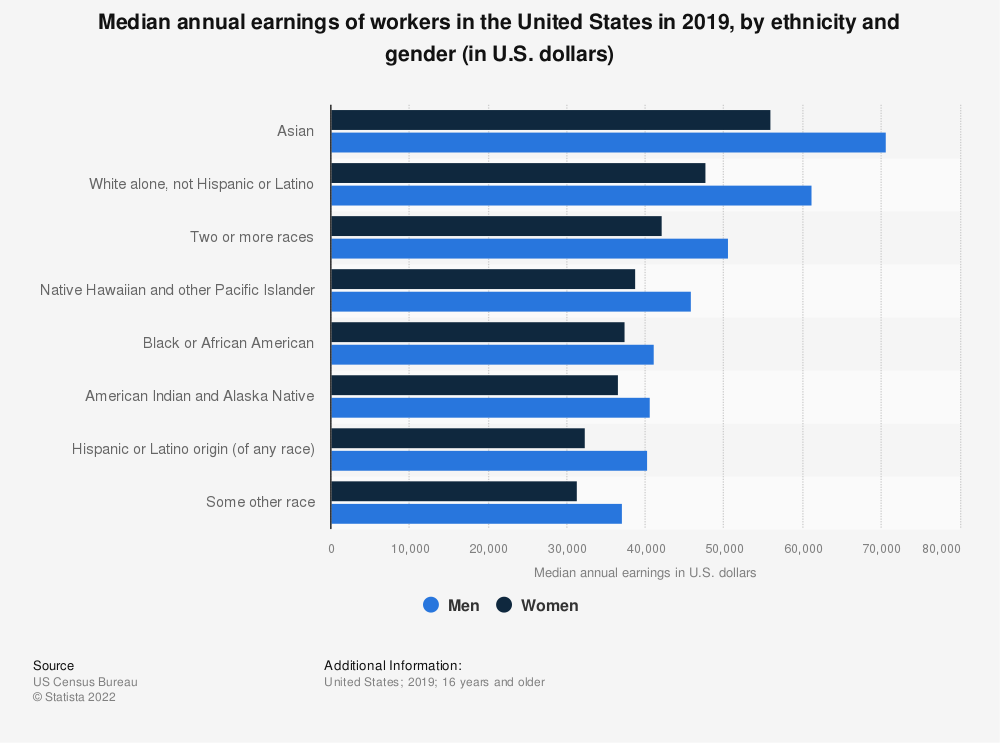

The outlook is particularly challenging for people who encompass intersectional diversity, such as Black women who are single heads of households. Barriers to employment due to sexism, racism, income, parental status, and urban residence further restrict employment and advancement opportunities. These barriers are highlighted by looking at the median annual earnings for workers in Figure 8.7. Worker income represented in the table for 2019 shows Latina women earn far less than other intersectional groups of race and gender.

Figure 8.7. Median annual earnings of workers in the United States by ethnicity and gender (in U.S. dollars), 2019. For all ethnicity categories, women earn less than men.

Transgender workers face high levels of discrimination, even though federal laws regarding workers’ rights protect them. Transgender workers have unemployment rates three times higher than non-transgender people, leading to economic instability (James et al. 2016).

Gender discrimination in the workplace has a long history, but progress is being made toward equal opportunity. Societal attitudes on gendered workplace stereotypes, such as what nurse Anderson encountered and pushed to change, can help move or dissolve workplace barriers for all genders. Labor force opportunities for all genders have changed due to diversity, equity and inclusion trainings, mentoring programs, and expanded access to childcare.

In early 2022, signaling another seismic shift in creating inclusive workplaces, the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) added the nonbinary self-identification option to discrimination report forms. Although times many institutional barriers have been removed from the workplace, disparities continue for access, placement, benefits, and promotions.

8.3.1 Invisible Barriers

Although women make up nearly half of the US workforce, only about 15% of Fortune 500 companies had female Chief Executive Officers (CEOs) by early 2022. This is a notable increase from 1.4% in 2002 (Buchholz 2022). The glass ceiling is the lack of advancement opportunities for non-males in high-level positions. This invisible barrier, due to a variety of factors, prevents non-males from achieving positions of power. Power in the workplace may include deciding how to spend the company’s money, who gets hired or fired, or what products to make.

In some industries, such as nursing, non-traditional gender workers are advanced at a higher rate. This quick movement from entry-level to power-holding, higher-paying leadership jobs is called the glass escalator. Males are non-traditional gendered workers in the nursing profession, making up 12% of nurses in 2021 (BLS 2021). Yet somehow, nearly half of nursing leadership roles are held by men. Researchers attribute this phenomenon to both the glass ceiling and the glass escalator. Research has shown that White males mostly benefit from the escalator while male nurses of color do not (Bradford and Bradford-Stevenson 2021).

Sociologists studying the workplace found another type of gender inequity, the pattern of behavior known as the glass cliff. This occurs when women are purposefully promoted into positions with a high risk for failure. This typically occurs when companies are already experiencing problems. Promotions with significant increases in pay and responsibility are difficult to pass up, even with the likely harmful outcome. Research shows that when women are placed on a glass cliff, this reinforces the stereotype that they are poor leaders (Kagan 2022).

Women on the glass cliff have higher-level roles in companies, but this is still not common overall. Many women find themselves stuck on the ground floor of the employment power ladder. The sticky floor refers to positions typically held by women, where advancement to the next level of power is difficult. Poorly paid and unstable jobs, such as entry-level, administrative, and human service workers, are particularly vulnerable to the sticky floor syndrome. If women in these roles lack formal education or financial stability, they are not often able to leave these dead-end jobs.

Companies can work on mitigating the glass ceiling, glass escalator, glass cliff, and stick floor in many ways. To start, fellow employees and corporate leaders need to recognize the existence of these workplace issues. Human resource departments or outside consultants can use diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives to openly discuss these problems in a safe space. Companies in difficult situations that promote women and people of color into professionally hazardous roles can ease the negative impact on employees by creating a culture of diversity and mentoring for success in higher executive levels.

8.3.2 Leadership Gendered as Male

Men are traditionally thought of as able to keep the attention of large groups of people due to the “authority in their voice,” meaning a lower tone typical of male voices. Higher pitched or softer-toned voices are considered feminine and soothing, thus not as attention-grabbing. This also translates to the workplace when women speak. Research has shown we all have internal biases about how others speak, leading to workplace discrimination (Ro 2022). Transgender workers have an especially tough time navigating professional gender biases. Their natural voice tone may not match societal expectations of their presented gender’s outer appearance. These biological variations have been the basis of gendered stereotype behaviors, thus expectations for what constitutes acceptable business leadership behaviors.

Gender self-presentation is also intertwined with the workplace. What we wear, our hair choices, body modifications (piercings and tattoos), and use of cosmetics influence how others see us. In many industries, “professional” clothing is a dark-colored suit with a dress shirt and tie, which is traditional masculine workplace attire. Wearing a suit then means you should be taken seriously and have excellent knowledge about a subject. Suppose you wear clothing with pastel shades or flowery patterns, which are considered stereotypically female. In that case, you might be viewed as not committed to your profession, not as intelligent or reliable. Societal pressure to adhere to masculine normative workplace clothing is evidenced by women and nonbinary altering their workplace attire to more closely match men’s traditional styles rather than men changing their clothing choices to match women’s.

Figure 8.8. Professional people face obstacles in the workplace through gender specific and Euro-centric normative expectations for presentation of self.

Black women, in particular, experience discrimination based on the presentation of natural hair textures and styles in the workplace. Figure 8.8 shows professional people with non-Euroccentric hairstyles. Wearing a non-Eurocentric hairstyle has negatively affected Black women’s employment and promotion opportunities into leadership roles (Koval and Rosette 2021). Women of color have been litigating for years for the acceptance of natural hair in the workplace, often with inconsistent outcomes.

To address this workplace barrier directly, the United States House of Representatives passed a bill in March 2022 that “prohibits discrimination based on a person’s hair texture or hairstyle if that style or texture is commonly associated with a particular race or national origin. Specifically, the bill prohibits this type of discrimination against those participating in federally assisted programs, housing programs, public accommodations, and employment. Persons shall not be deprived of equal rights under the law and shall not be subjected to prohibited practices based on their hair texture or style” (Congress.gov 2022).

The Public Broadcasting Service news report by Yamiche Alcindor in figure 8.9 explores barriers experienced by people due to their hair in society. Watch the report to learn more about how leadership in the workplace is viewed through an intersectional lens including gender and race.

Figure 8.9. This PBS Newshour video report discusses how hair discrimination impacts Black Americans in their personal lives and the workplace.

Employees who wear non-stereotypical or non-Eurocentric workplace clothing for religious reasons, such as the hijab, have also faced barriers to employment and advancement at work. Researchers found employees who experienced discrimination based on wearing women’s religious garments reported decreased satisfaction in their workplace (Ali, Yamada, and Mahmood 2015).

Transgender workers experience unique challenges in the workplace concerning appearance. As many as 53% of transgender workers responding to a 2015 survey said they had to “hide their identity to avoid anti-transgender discrimination at work in the past year” (James et al., 2016). Discrimination against transgender workers comes in many forms, including firing or not being hired due to being transgender, purposeful use of incorrect pronouns, bullying by colleagues and customers, and lack of gender-neutral bathroom access.

Many companies have begun to realize the importance of steering away from traditionally masculine workplace modes of dress and behavior expectations. Companies are responding to evidence that diverse workplaces create a more welcoming and, thus, productive environment. Hundreds of organizational leadership books are on the market, each espousing advice on becoming a better leader or changing traditional practices to promote a more innovative organization. Is a strong handshake truly a sign of a person’s business expertise? These books often fail to mention the problem of sexism and gender discrimination in the workplace and how embedded it is in organizational culture. It’s difficult to “lead by example” or “manage talent” when no one listens to you; you are discounted as unreputable or not intelligent based on the tone of your voice.

8.3.3 Lack of Childcare

Appearance and behavioral standards are not the only workplace barrier for employees. Workers may be responsible for taking care of children or other adults. Lack of childcare or caring for an elderly person creates physical and emotional strain for many workers. Women have long been considered to have natural, internal instincts for raising children. Such expectations can create barriers for women in the workplace when they are expected to be the primary caregiver, although, for many families, they are not. Research has shown concerns for children’s care while at work cause increased stress. Caregiving for children or the elderly is stressful and takes an emotional toll on the caregiver. Negative health outcomes for caregivers exist for all gender caregivers, yet women take on a disproportionate amount of caregiving globally (Sharma, Chakrabarti, and Grover 2016).

Finding and affording daycare became an increasing concern for low-wage workers through the late 20th century as more women gained full-time employment. Although the percentage of women in the workplace peaked in the late 1990s, the need for safe, affordable daycare and elder care persists today.

Data from late 2020, about six months after the COVID-19 pandemic, showed daycare as an increasing problem for all gender parents. With many schools closed then, women were more likely than men to express increased responsibilities and difficulties balancing work and childcare responsibilities. (Schaeffer 2022). By June 2021, another study found that “Globally, women took on 173 additional hours of unpaid child care last year, compared to 59 additional hours for men.” (Avi-Yonah 2021). This is nothing new, as women have traditionally assumed responsibility for the care of family members.

Eldercare is another barrier many women face in the workplace. As women’s careers progress, they are also unequally responsible for the care of aging parents. Known as the sandwich generation, people who support the needs of their children and parents simultaneously can find these responsibilities strain finances, time, and work commitments. As women’s roles in the workplace have become more socially normed over the last 30 years, men’s participation as caregivers for elderly relatives has increased. One study found that “women who cared for ill parents were twice as likely to suffer from depressive or anxious symptoms as non-caregivers” (National Center on Caregiving at Family Caregiver Alliance, 2003). As the primary caregivers for elderly parents and relatives, women’s health is negatively impacted, yet many report positive emotional benefits to this role as shown in figure 8.10.

Figure 8.10. Senior people have a lifetime of experiences to share with young people.

Low-income, typically people of color, and single heads of households, which are historically predominantly women, face intensified daycare and eldercare burdens due to ever-increasing costs. Recent data shows that “Oregon is ranked 14th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia for most expensive infant care” (Economic Policy Institute 2020). The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which studies these trends recognizes affordable care as “no more than 7% of a family’s income” yet “Infant care for one child would take up 22.2% of a median family’s income in Oregon” (Economic Policy Institute 2020). When faced with childcare challenges, men who are single heads of households are more likely to be able to adjust their work responsibilities to accommodate childcare needs.

Making childcare more affordable and accessible to all families is important, especially for single parents. This means women in particular can be more stable employees, excel in the workplace, and build wealth over time. It also reduces the cycle of poverty for single-parent families. Support networks do exist for all gender caregivers. Private and public agencies can help with emotional and physical support. They can also help with financial advice and resources as workers stuck in low-wage positions find it difficult to move out of poverty when faced with ever-increasing childcare costs.

8.3.4 Pay Discrepancies

All genders experience pay discrepancies. What are some of the reasons for this and why does this happen? From the time people first enter the workforce, whether that is directly after high school or after completing a degree, women are typically offered lower pay for the same type of work as men. Women also are more likely to accept their first pay offer rather than negotiate a higher start salary. Given those two early obstacles, pay over one’s professional lifetime varies greatly by gender. “A typical woman who works from age 16 to 70 will make $590,000 less than a man working an identical span” (Wilson 2019). Differences in pay early on build over a worker’s lifetime. Income affects opportunities to buy a car, own a home, invest in retirement, pay for a child’s education, and afford healthcare.

In 2022, across all professions, women make approximately 82 cents per every dollar men make (Payscale 2022). Native American women fare the worst when race and gender intersect, making approximately 71 cents compared to White men’s $1.00 (Miller 2022). Much of this has to do with society’s gendered norms steering women into low-wage positions. However, some progress has been made in pay equity for professions where men and women perform the same job. In a controlled comparison of data where areas such as “job title, education, experience, industry, job level, and hours worked” are the same, women make 99 cents per every dollar men make. This is incredible progress over time, yet as one report notes “the gender pay gap is closing over time but at glacial speed” (Payscale 2022).

Due to higher rates of unemployment as well as hiring and promotion discrimination, transgender workers are heavily affected by workplace and gender-based pay inequity. The ramifications are that transgender people are twice as likely to live in poverty than cis-gendered people (James et al. 2016).

Gaps in career progression due to pregnancy, childbirth, childcare, and eldercare issues restrict promotion potential which is an additional source of pay inequity over a lifetime. In general, for all workers, a female parent’s pay is about 74 cents of a male parent’s (Payscale 2022). Female heads of households are acutely susceptible to fluctuations in the economy. This can bring about role conflict, which is a situation in which contradictory, competing, or incompatible expectations are placed on an individual by two or more roles held at the same time. Role conflict for single parents finds them struggling to fulfill work obligations while also meeting their family’s needs. The instability of work can negatively impact employee finances and seriously impede wealth building for their future retirement.

As we discussed at the start of the chapter, education can significantly affect the gender pay gap. A fluctuating economy has a significant impact on pay inequity across genders. Women with less than a high school education saw their employment participation drop by nearly 13% from 2019 to late 2021 compared to an almost 5% drop by men with the same education. Alternatively, workers with at least a bachelor’s degree saw an increase in employment during the same time, regardless of gender.

Rising childcare costs and a lack of qualifications in higher paying positions due to the types of degrees being earned, means women have difficulty being stable participants in the workforce. Increasing access to education and supporting workers to succeed in formal education will strengthen women and transgender stability in the workforce during economic recessions. This workplace stability creates positive outcomes for children whose families are struggling.

8.3.5 Pay Discrimination

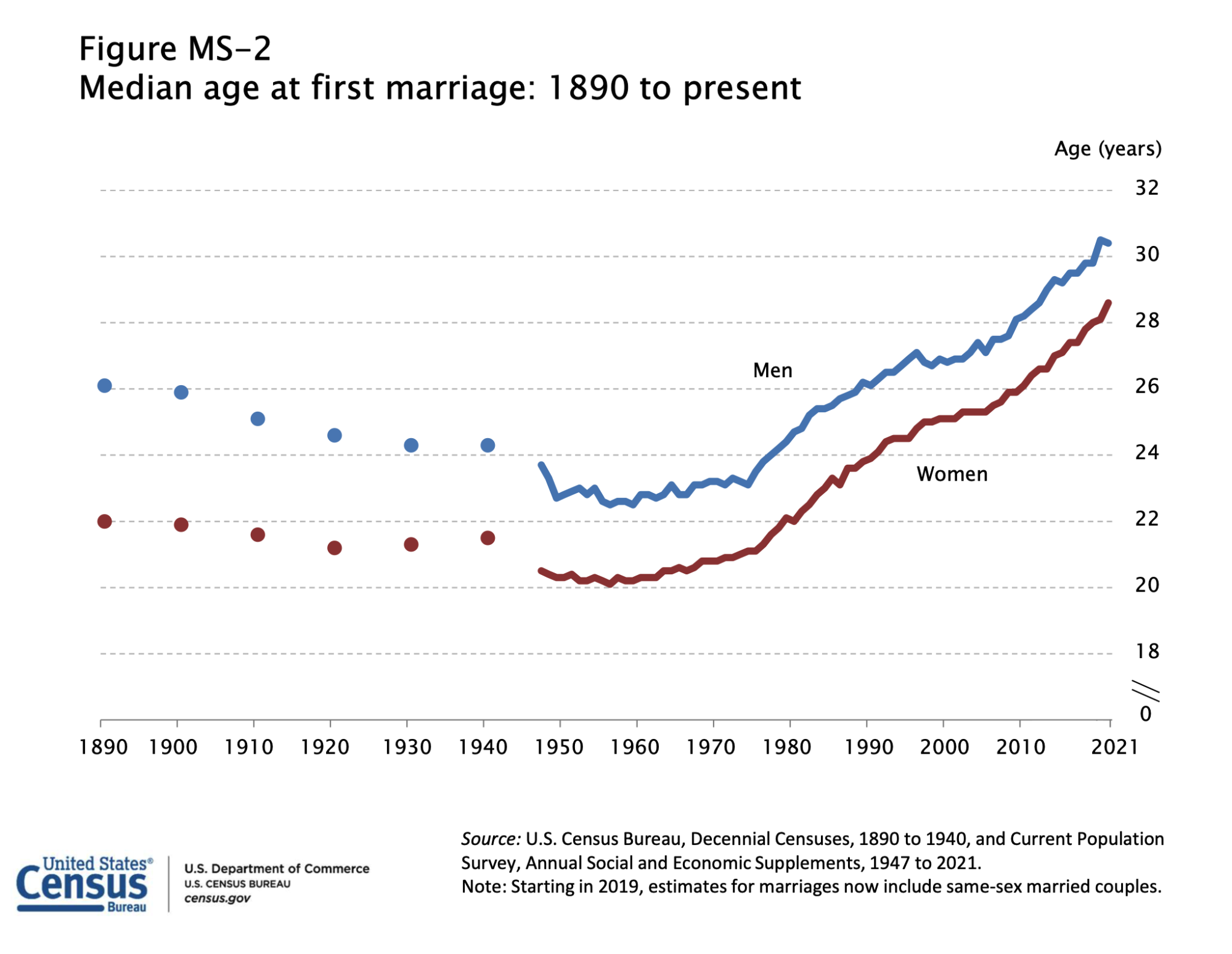

Single parents face discrimination based on societal assumptions that their parental role may interfere with them fulfilling their job responsibilities. Societal gender expectations we have today are rooted in historical, societal norms. In the early 1900s, laws existed legally forbidding married women from working. There were also societal pressures encouraging women to leave the workforce when they got married. Even though marital age has risen over the last 50 years, the public’s perception that women cannot physically work or should not participate in the workforce when married or pregnant persists. Figure 8.11 shows the changing dynamic of age at first marriage historically. There is a correlation between when women increasingly earned bachelor’s degrees in the 1980s and 1990s with the noticeable increase in the age at first marriage as seen on the chart.

Figure 8.11 Median age at first marriage, 1890-present. As women strengthened participation in the workforce, the age of first marriage increased for the genders measured.

As more women entered the primary sector labor market and assumed white-collar roles, greater protections were demanded for working parents. Changing societal norms acknowledged discrimination against working parents, including nursing or adoptive parents. The Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) was passed in 1993. The FMLA protects employees from firing or losing benefits while away from work for specific family or medical reasons. Although legal protections exist for pregnant people, such as the Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA) passed in 1978, employers still discriminate against pregnant workers. Newly married individuals may be perceived as looking to start or expand a family, thus unreliable as future workers. In 2020 just under 400 pregnancy discrimination lawsuits were filed in federal court (Sear and Goldstein 2021). Parents on parental or adoption leave may miss out on meetings or other work, which is then used to justify passing them over for promotions, thus reinforcing pay inequities.

Access to pregnancy and family leave policies can strengthen workforces across all industries and all levels of employment. Company cultures flexible with family leave will see positive returns from their employees and the company overall. One study found that paid-leave policies “led to improved infant health, with the largest effects on disadvantaged African American and unmarried mothers” (BLS 2019).

Black women are especially susceptible to barriers in the workplace due to “unacceptably high rates of chronic illness as well as tragically high rates of maternal and infant mortality. In fact, Black women, as well as their infants, are significantly more likely to die in the weeks after birth than are any other group of people” (Milli, Frye, and Buchanan 2022). Chronic illnesses due to a lack of access to affordable healthcare and concerns about taking time away from work for medical care negatively impact not just the workers, but companies who have to deal with prolonged gaps in their workforce. Black female workers’ medical instability can also harm their chances of being hired or promoted due to misperceptions of them being unreliable workers.

This catch-22 is a cycle of oppression for women and people of color in the workforce. In a 2019 report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Latinx workers were found to have the lowest access to paid leave for childcare or eldercare of all race categories. When faced with these life challenges, Latinx workers do not have financial or employer support for missing work (BLS 2019), which creates financial hardships. Taking time away from work for childcare or eldercare crises may also indicate to employers the worker is unreliable or not focused on their job.

The intersectional nature of some workers’ demographics and life experiences can negatively affect their pay and work opportunities. As discussed earlier in this chapter, companies have concerns about employees who do not look “trustworthy” or “presentable” due to natural hair, body modifications, or non-mainstream workplace clothing. Such concerns are the basis of unconscious and conscious biases in the hiring and promotion processes.

8.3.6 Attempted Remedies

There are many ways to address workplace inequities. Have you ever been part of a mentoring program or had a workplace role model? Some companies have created mentoring programs for new employees. Matching new employees with more experienced workers creates an attachment to the company, eases the transition to a new company, and can increase retention in the long term.

Figure 8.12 Many workplaces have been increasing access for disabled people in the workplace, although obstacles persist such as stigma and access to supportive resources.

Some larger companies have made their workplace more worker-friendly for all employees by offering single-occupant restrooms, accessible workspaces for all abilities as shown in figure 8.12, on-site dry cleaning, pet sitting, and gyms. To support all genders in the workplace, some companies have gender-neutral dress codes, offer daycare and eldercare centers, and pay for formal education such as professional certifications or advanced degrees. Such benefits, however small, can ease role conflict and role strain, especially for women, nonbinary, and transgender workers, thereby increasing long-term participation and advancement in the workplace.

8.3.7 Licenses and Attributions for Barriers to Advancement in the Workplace

Figure 8.7 Chart by Statista Research Department is in the Public domain.

Figure 8.8 Photo by WOCinTech is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 8.9 Screenshot of How hair discrimination impacts Black Americans in their personal lives and the workplace © PBS is included under fair use.

Figure 8.10 Photo by 963797 is licensed under the Pixabay License.

Figure 8.11 Chart by United States Census Bureau in the Public domain.

Figure 8.12 Photo by Disabled And Here is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Role conflict definition is from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Barriers to Advancement in the Workplace” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.