8.4 Work Inside the Home

What do you consider work? Do you consider work as loading and running the dishwasher before catching a train on the subway? What about washing a load of laundry after an eight-hour restaurant server shift? It is the mundane everyday activities such as shopping for groceries, making meals, cleaning the bathrooms, and various other tasks, that make households that are less often viewed as official work.

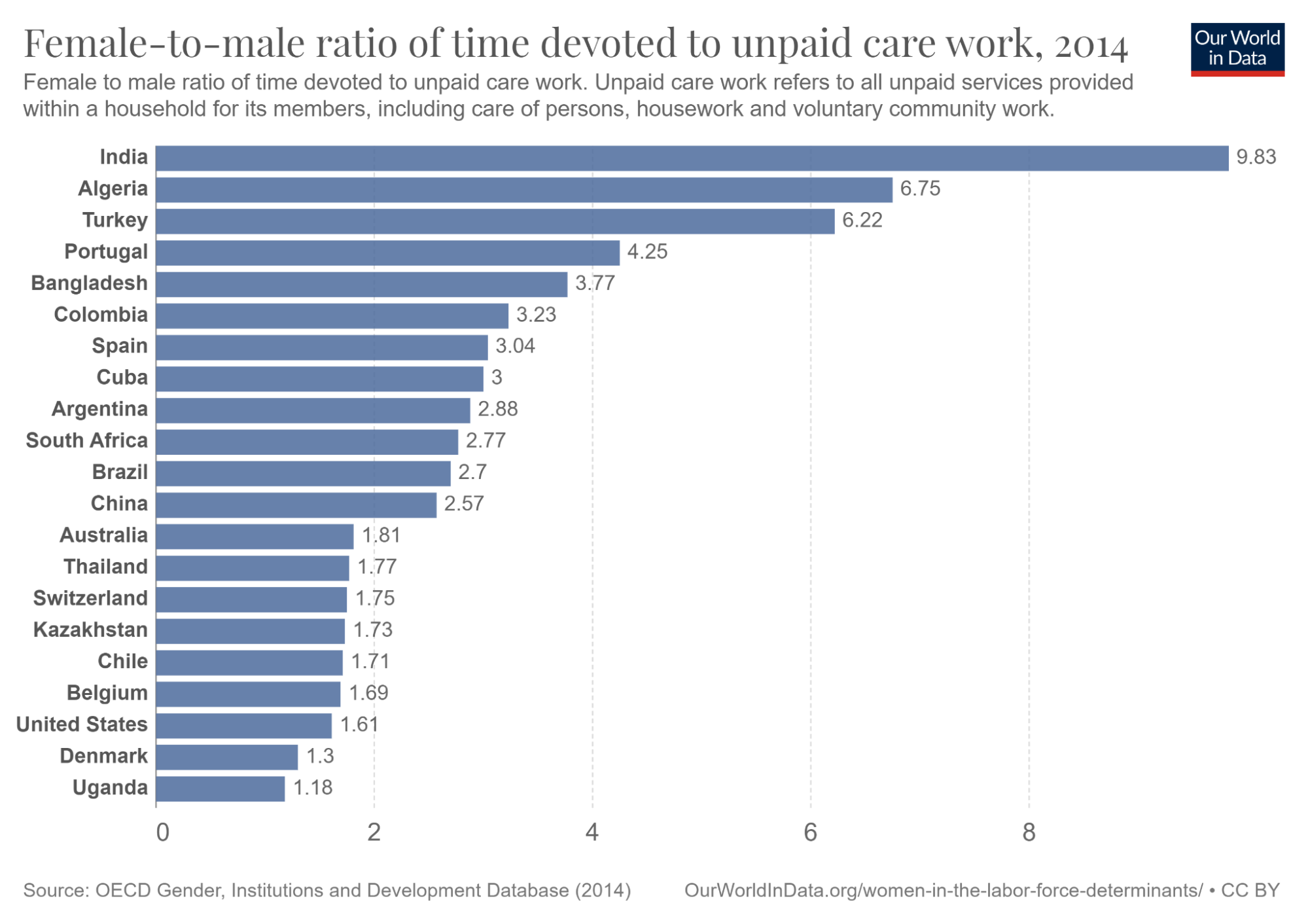

Researcher Arlie Hochschild has long studied this phenomenon known as the second shift (Hochschild, 1990). She found that women are more likely than men to perform work inside the home in addition to working outside the home. Figure 8.13 shows females are more likely to bear the weight unpaid care work across many countries. The balance of household responsibility has changed as companies recognize the need for employee-life balance, cultural acceptance of stay-at-home Dads, and the growing egalitarian ideologies between partners (Blair-Loy 2015).

Figure 8.13 Female-to-male ratio of time devoted to unpaid care work, 2014. Women spend substantially more time than men on unpaid care work in many countries.

Shifting family dynamics due to re-partnering, marriage, divorce, or death create unique challenges for all families experiencing these significant transitions. Expectations of chore responsibilities inside the home may vary for members who live across multiple residences. Differing household rules or strained relationships with new family members can cause household conflict. The concept of boundary ambiguity helps us understand that not all families, and thus their expectations for household work, are the same. Boundary ambiguity “is defined as the family not knowing who is in and who is out of the system” (Boss and Greenberg 1984:535). This idea encompasses physical and psychological presence or absence, as graphically presented in figure 8.14.

Figure 8.14 For many children and adults, changing family structures can bring about boundary ambiguity, meaning who is part of a family and expectations for one’s role in the family is not always clear.

Transgender and gay relationships create unique challenges for households. Research by Jenkins (2013) studied gay male families where one partner was the children’s biological father. Boundary ambiguity was highlighted due to institutional factors such as “heterosexism, legal decisions, and beliefs and practices encouraged in religious institutions” (Jenkins 2013) as well as interpersonal factors such as “the relationship of the gay parent with his ex-spouse and children” (Jenkins 2013).

8.4.1 Gendered Division of Labor

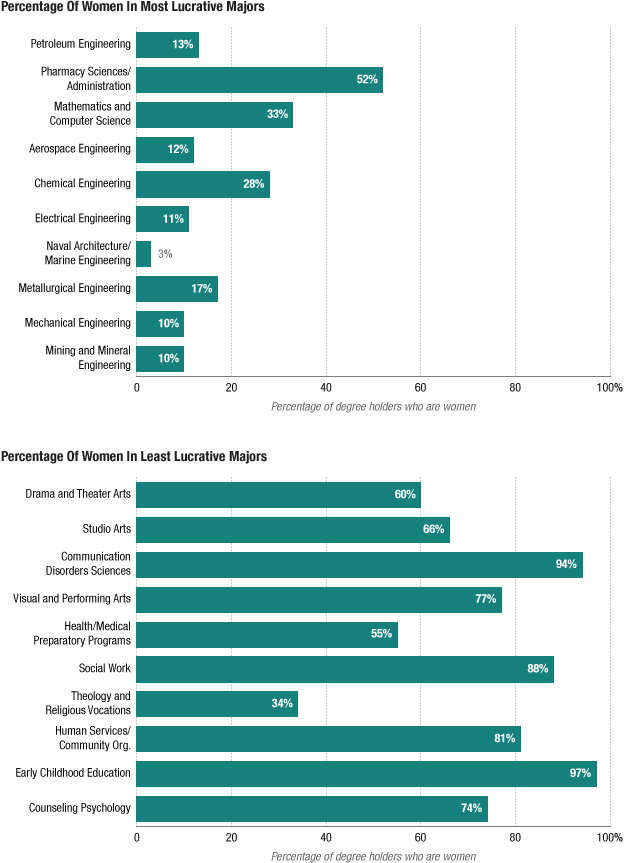

Labor force participation has changed over time for all genders. Until the mid-1990s more men than women were paid hourly wages. That shifted in the 1990s as the number of female hourly wage workers outpaced males. “From 1970 to 2019, the proportion of women ages 25 to 64 in the labor force who held a college degree quadrupled, whereas the proportion of men with a college degree a little more than doubled over that time“ (BLS 2021). Figure 8.15 shows gender participation for men and women based on the highest and lowest-paying jobs.

Although women are gaining advanced degrees and access to some male-dominated jobs, they are still more likely to be employed in society’s lowest-paying industries. Women’s participation in some industries includes “18.7 percent of software developers, 27.6 percent of chief executives, and 36.4 percent of lawyers were women, whereas 88.9 percent of registered nurses, 80.5 percent of elementary and middle school teachers, and 61.7 percent of accountants and auditors were women” (BLS 2021). More recently, the global pandemic caused women to leave and not return to the workforce at a higher rate than men.

Figure 8.15 Percentage of women graduating in the highest paying and lowest paying majors. High-paying jobs which have high societal prestige are filled mostly by men. Women more often fill jobs in the secondary sector labor market which has low societal prestige.

As we learned earlier in this chapter, societal-wide gender norms exist for certain jobs. Changing ideologies have driven employers to reclassify job titles from gender-specific terms like “waiter/waitress” to gender-neutral “server” and “stewardess/steward” to “flight attendant.” Stigma, stereotypes, and long-standing gender norms create a cycle of provoking children to look to professions and see only a narrow representation of future workplace possibilities. Adult professionals of all genders, races, sexualities, and life experiences can mentor youth and help them see themselves in a variety of professions.

8.4.2 Emotional Labor and Kin-Keeping

Interactions with the public or customers are common across most workplaces. Many companies have written expectations for how they expect workers to perform their roles and provide a detailed script to employees. Employees may find themselves performing emotional labor when interacting with customers. Workers who perform emotional labor hide their emotions in the workplace to ensure a pleasant and consistent customer experience. Females dominate jobs with emotional labor such as education and healthcare industries where there are frequent interactions with customers.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, women traditionally take on the highly emotional roles of childcare and eldercare providers more often than men. It follows that women are more likely than men to perform relationship-building functions within families, too. The effort to build and maintain relationships between family members is called kin-keeping.

Although kin-keeping increases the likelihood of stress due to role conflict between obligations, especially for women, kin-keeping can have positive benefits (Gerstel and Gallagher 1993). One study looked at African-American grandmothers caring for their grandchildren. Interactions with grandchildren positively impacted the grandmothers’ workplace readiness. An additional benefit was that grandmothers’ workplace experiences could be shared with grandchildren (Stephens 2019).

8.4.3 Licenses and Attributions for Work Inside the Home

“Work Inside the Home” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.13 Female-to-male ratio of time devoted to unpaid care work by Our World in Data is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.14. Photo by Gerd Altmann is licensed under the Pixabay License.

Figure 8.15 “Percentage of women graduating in the highest paying and lowest paying majors” is from “Why Women (Like Me) Choose Lower Paying Jobs” © NPR and is included under fair use. Source: Anthony Carnevale, Georgetown University. Credit: Quoctrung Bui.