9.2 Socialization of Gender Inside Healthcare

Gender discrimination in society negatively affects all genders’ ability to obtain medically necessary care. The issue of discrimination in the healthcare system has been widely studied. Researchers find that “While it is true that women live longer than men on average, they experience higher rates of ill health during their lifetimes. It is likely that gender discrimination and inequity contribute to this.”(Villines, 2021). What happens when you don’t feel well? Do you take time off from work or do you have to work? For many people, not working means not being able to pay for food or rent, so they must work while sick. Taking time off work to be sick is a right covered by the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) we learned about in Chapter 8. Sociologists also have a term for the expected patterns of behavior attached to individuals who are sick and those that take care of them, which is the sick role. Societal expectations based on gender norms may affect your sick role day to day. Your sick role may also affect how healthcare providers receive you.

9.2.1 The Ideal Body

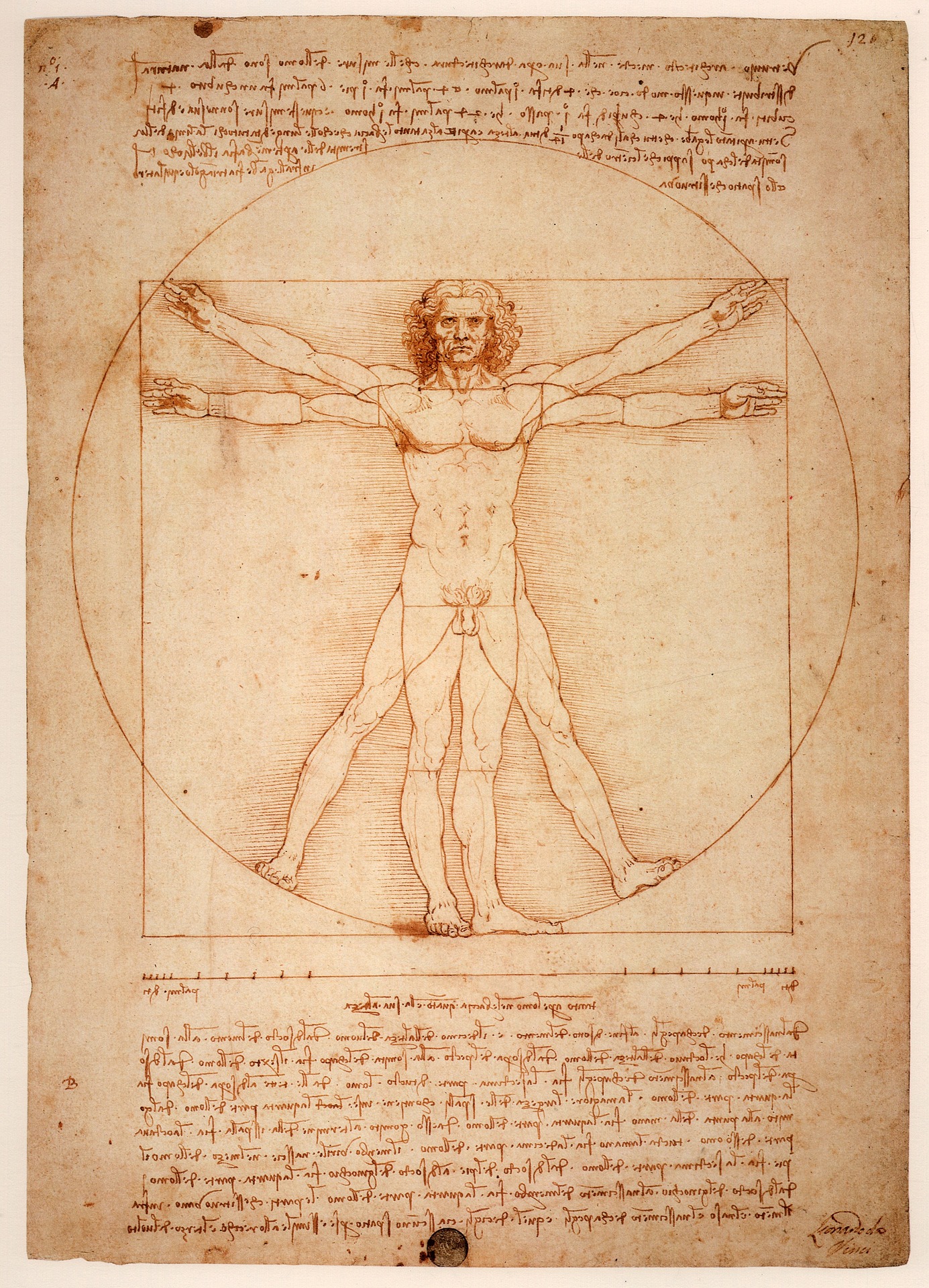

What do you think of the ideal body? Images of the ideal body type go way back in human history including cave drawings. More recently, the Vitruvian Man by the famous artist Leonardo Da Vinci was created in the late 1400s. See the famous drawing in figure 9.2.

Figure 9.2. The Vitruvian Man has been considered the societal and scientific normative body and feature type for centuries.

Da Vinci and other artists of the time initially created images of an ideal person to explore the proportions of the human body. In the years since, this image has become a societally recognized representation of a healthy, standard body throughout art, media, and science. Our culture today uses this image to show that males are the basis of normal images of humans. People who do not look like the Vitruvian man are not considered the norm. When medicines and medical procedures are tested, gender and people of color are often not sufficiently represented in clinical trials.

Not recognizing the variety of human bodies and cultures in society presents a dangerous standard in healthcare. A 2022 study showed “those that often face the greatest health challenges, are less able to benefit from these discoveries because they are not adequately represented in clinical research studies. While some representation progress has been made by including White women in clinical trials and research, there has been little progress in the last three decades to increase the participation of racial and ethnic minority populations. This underrepresentation is compounding health disparities, with serious consequences for underrepresented groups and for the nation” (Bibbins-Domingo and Helman 2022).

The United States Military revealed one such devastating consequence. Military protective equipment has always been built for a male’s physique. Women in the military have been at a higher risk of injury and death due to poorly fitted protective equipment. “Ill-fitting armor gave snipers a clean shot” (Price 2021). Only in the last few years have researchers produced armor specifically built for women’s bodies which are lighter in weight and better able to cover essential organs. Figure 9.3 shows female soldiers fitting their protective gear.

Figure 9.3 Spc. Arielle Mailloux gets some help adjusting her prototype Generation III Improved Outer Tactical Vest from Capt. Lindsey Pawlowski, Aug. 21, 2012, at Fort Campbell, Ky. Both Soldiers are with the 1st Brigade Combat Team Female Engagement Team, 101s.

Another example of the battle to include non-traditionally male body types in research includes motor vehicle companies. Vehicle crash test dummies often represent men’s body standards from the 1970s, leaving women open to a higher risk of injury and fatality. Car safety advocates have demanded body forms besides standard males for safety tests for years, yet they are still not part of required vehicle safety testing. Data on vehicle accidents show “that for a female occupant, the odds of being injured in a frontal crash are 73 percent greater than the odds for a male occupant.“ One study also found that “female drivers and right front passengers are 17% more likely to be killed in a car crash than a male occupant of the same age” (Barry 2019). Not including all genders in health and medicine-related research can have dire, even fatal, consequences.

9.2.2 Gendered Pursuit of Healthcare

Women are more likely to have mental health issues such as eating disorders, anxiety, and depression. “Women are also 1.5 times more likely to attempt suicide than men, although men are more likely to die by suicide” (Villines 2021). This inequity in mental health recognition and services is more pronounced in cultures with higher gender inequity. This means when women have poor working conditions (such as access to healthcare and exposure to toxic substances), poor living conditions (such as exposure to poor quality water and physical violence), and they are more likely to experience mental health problems. Medical professionals may tell women they are having an emotional reaction to a situation rather than taking their physical medical emergency seriously.

9.2.3 Transgender and Intersex Healthcare

Intersex, as we learned in Chapter 2, is the term used to identify people whose biology encompasses both male and female attributes including ambiguous genitalia. When a baby is born, it is not always obvious when looking at their physical genitalia if they are biologically male or female. Societal pressures to assign a person a binary gender identity, male or female only, at birth are significant. Starting in the 1950s, as medical technology became more accessible, surgeries to assign intersex children a binary gender occurred more frequently. Families and medical professionals wanted to “correct” the child’s lack of defined gender normative biological presentation.

Medical professionals and parents labeled intersex children with one of the binary genders, then performed surgery to construct male or female normative genitalia. Early infant surgeries were not without risk, as patients could undergo continued surgeries, hormone treatments, and internal confusion over their own gender identity throughout adulthood. In 2006, medical professionals, families, and intersex people met to support, share information and create awareness for intersex people.

Now, the medical diagnosis for an intersex individual, disorder of sexual development (DSD), is used “to describe any condition in which sex-related chromosomes, molecules, and/or internal organs do not develop in a way that could be classified as male or female. It also recommended against the use of terms such as male/female, hermaphrodite, and pseudohermaphrodite because these terms can be confusing and may carry negative connotations” (Viau-Colindres et al. 2017: 1).

There has been pushback by both families and medical professionals in recent years on the practice of “corrective” surgery which assigns a particular gender at birth. Gender dysphoria, or conflict between assigned and biological gender, can happen, “with rates up to 50% for certain conditions regardless of the sex assigned” (Viau-Colindres et al. 2017: 2). Families and the medical community are continually working on how to approach the highly complex issue of early binary gender assignment through surgical intervention and societal gender norms for intersex people

9.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Socialization of Gender Inside Healthcare

Sick role definition is from the Open Education Sociology Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.2. “Vitruvian Man” by Leonardo Da Vinci, Pixabay is licensed under the Pixabay License.

Figure 9.3. “Spc. Arielle Mailloux gets some help adjusting her prototype Generation III Improved Outer Tactical Vest” by U.S. Army is in the Public Domain.

“Socialization of Gender Inside Healthcare” by Jane Forbes is licensed under CC BY 4.0.