3.3 Who Do You Love?

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, early sociologists viewed same-gender sexual attraction and behavior as deviancy from “normal” or “natural” sexual attraction and behavior. But is sexual attraction between people of different genders the only normal or natural form of sexual attraction? Sexual attraction and intimacy between people of the same gender have always existed in human societies, with varying degrees of social acceptance. In non-human animals, more than 1500 species of animals, including many primates, have been documented engaging in same-gender sexual activity and forming even long-lasting same-gender pair bonds (Gómez et al. 2023). Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that same-gender sexual behavior is natural (it is common in the natural world) but that human societies tend to regulate sexual behavior by socially constructing categories of sexual behavior that are acceptable or “normal” and unacceptable, or “deviant.”

Recall from Chapter One that heteronormativity is the social enforcement of heterosexuality, in which there are only two genders, that these genders are opposites, and that any sexual activity between people of the same gender is deviant or unnatural. So then, heteronormativity helps regulate sexual behavior within patriarchal societies. Sexuality is more than sexual behavior, however. Sexuality also includes sexual orientation. Sexual orientation refers to emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to other people; it is often used to signify the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the gender identities to which a person is most attracted (Southern Poverty Law, 2018). In other words, sexual orientation describes who we are sexually attracted to.

This section will engage our sociological imagination to understand the social struggle of people who have resisted heteronormativity and demanded full inclusion in society, including the right to fully embody their sexual orientation. The chart in figure 3.4 identifies many possible sexual orientations and includes words that may have been introduced quite recently. As you read through this section, keep in mind that aspects of the struggle for full inclusion are expressed in the evolving language we use to communicate ideas of sexual orientation, sexual behavior, and identity.

| Sexual Orientation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Asexual | People who do not experience sexual attraction or do not have a desire for sex. Many experience romantic or emotional attractions across the entire spectrum of sexual orientations. Asexuality differs from celibacy, which refers to abstaining from sex. Also, Ace, or Ace Community. |

| Bisexual | A person emotionally, romantically, or sexually attracted to more than one sex, gender, or gender identity though not necessarily simultaneously, in the same way, or to the same degree. |

| Demisexual | Someone who feels sexual attraction only to people with whom they have an emotional bond—often considered to be on the asexual spectrum. |

| Gay | People (often, but not exclusively, men) whose enduring physical, romantic, or emotional attractions are to people of the same sex or gender identity. |

| Heterosexuality | A term that describes an enduring physical, romantic, or emotional attraction to people of the opposite sex. Also straight. |

| Lesbian | Used to describe a woman whose enduring physical, romantic, or emotional attraction is to other women. |

| Pansexual | Used to describe people who have the potential for emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to people of any gender identity, though not necessarily simultaneously, in the same way, or to the same degree. The term panromantic may refer to a person who feels these emotional and romantic attractions but identifies as asexual. |

| Queer | Once a pejorative term, now reclaimed and used by some within academic circles and the LGBTQIA+ community to describe sexual orientations and gender identities that are not exclusively heterosexual or cisgender. |

| Same-gender loving | A term coined in the early 1990s by activist Cleo Manago, this term was and is used by some members of the black community who feel that terms like Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual (and sometimes the communities therein) are Eurocentric and fail to affirm Black culture, history, and identity. |

Gay Liberation

In rigidly patriarchal societies, being identified as homosexual carries serious social and sometimes legal consequences. This was especially true in the post-World War II period (1946 – 1968), identified by historians as a particularly harsh time in the U.S. Even though Kinsey (1948, 1954) estimated that at least 37% of men and 13% of women reported “some form of homosexual experience,” and roughly 10% of the men and 4% of the women who participated in the survey reported “extensive homosexual experience,” laws against sodomy and “cross–dressing” created a hostile and dangerous social climate for people who we now recognize as LGBTQIA+. Sodomy is an archaic legal term to describe oral or anal sex, generally between men. Cross-dressing is an archaic term to describe men who dressed as women or women who dressed as men. Neither term is commonly used now.

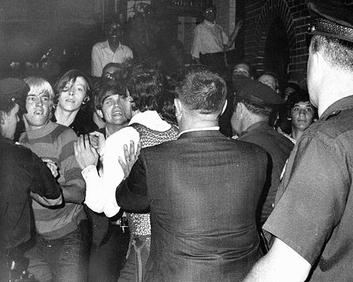

These laws were rigidly enforced in so-called vice raids of the bars and social clubs where gay men, lesbians, bisexuals, and trans people gathered to socialize (figure 3.5). This targeted persecution characterized homosexuality and communism as twin threats to the American family and freedom (Strub 2008).

Like feminists of the 1960s and 1970s, many African American gay men and lesbians were engaged in the civil rights movement. They adopted similar tactics to organize and support each other. The writer James Baldwin (he/him) and the civil rights leader Bayard Rustin (he/him), who both identified as gay men, were icons of the civil rights era and active in the early “gay liberation movement.” Baldwin called for Black and White Americans to “like lovers, insist on, or create, the consciousness of the others… that we might to end the racial nightmare, and achieve our country, and change the history of the world” (Baldwin, 1962, 105.). The shift in consciousness he called for included a shift towards full acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people.

Rustin helped organize the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his famous speech, I Have a Dream. After the famous Stonewall Riots in 1969, when patrons of the Stonewall Inn in New York City, including trans activists Marsha P. Johnson (she/her) and Sylvia Rivera (she/her), resisted police harassment and sparked a series of demonstrations by gay, lesbian and trans people in the surrounding neighborhoods (figure 3.5). Rustin described the action as a continuation of the civil rights movement and identified four actions that all oppressed people, including LGBTQIA+ people, must engage in: overcome fear, overcome self-blame, overcome self-denial, and engage in political, moral, and psychological action to create “an America where [people] cannot openly manifest hate” (1986).

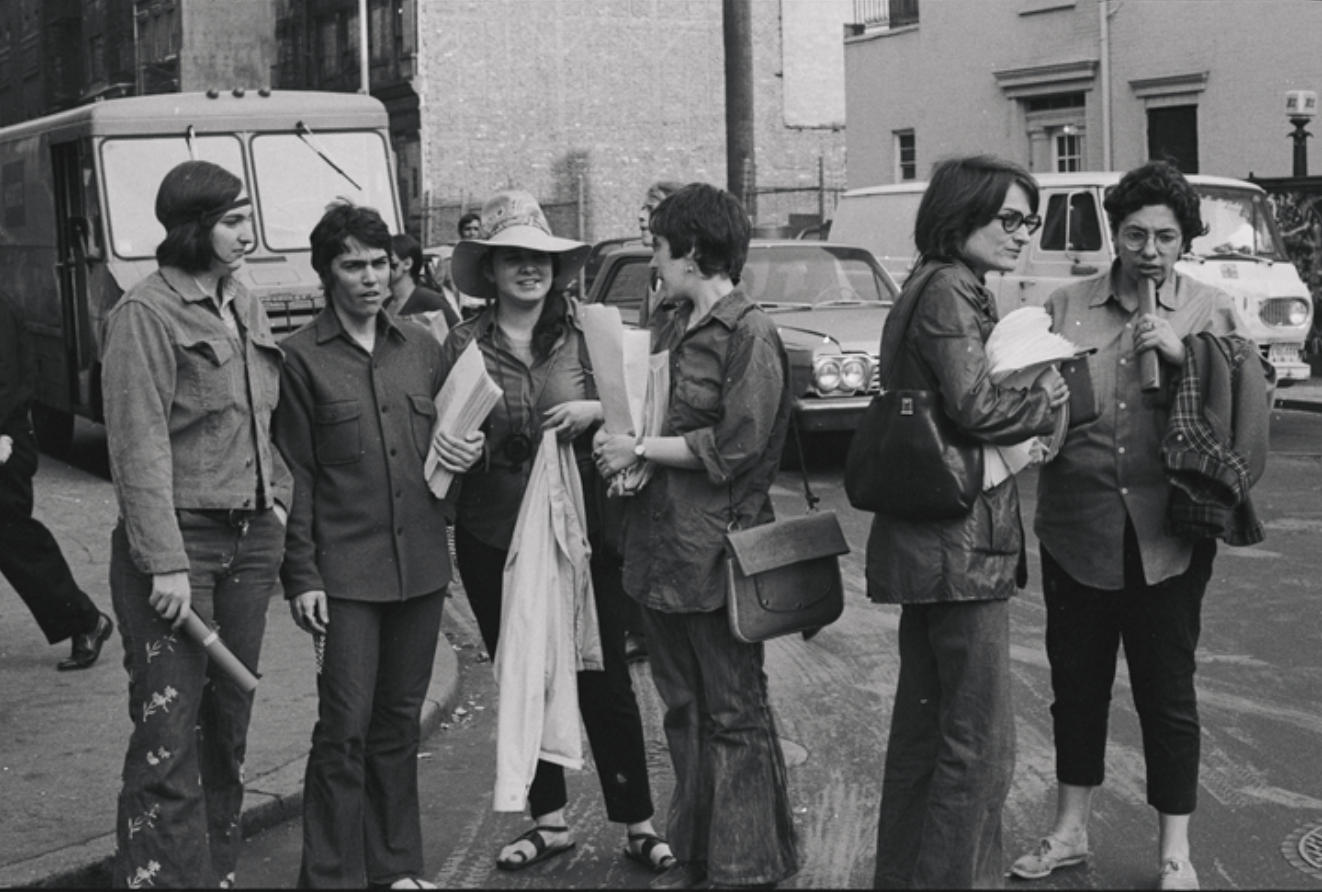

Many feminists in the civil rights era were weary of lesbians, and for a while, lesbians were excluded from feminist organizing. In 1969, the same year as the Stonewall Riots, Betty Friedan (she/her), author of the Feminine Mystique (1963), and the first president of the National Organization for Women (NOW) referred to lesbians as a “lavender menace.” In response, a group of self-described radical lesbian activists, including the writer Rita Mae Brown (she/her, shown in figure 3.6), adopted the name Lavender Menace and organized to confront NOW and secure full inclusion. Chapter Four will more fully describe the intersectional work of Black queer and trans women to define and create a coalition-based approach to mutual liberation

In 1979, lesbians, gay men, bisexual people, trans people, and their allies demonstrated political solidarity with the first March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights. Two years later, the HIV/AIDS crisis began to kill thousands of gay men, and public health efforts to identify and treat the virus were delayed by a lack of political will. An LGBTQIA+ coalition of advocates, including groups like ACT UP, the Lesbian Avengers, and Parents, Family, and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG), built a political base of power that helped to change public opinion about LGBTQIA+people and the political response to HIV/AIDS.

This coalition built a broad political base of LGBTQIA+ people and allies who organized in support of federal and state legislation that increased the penalties for hate crimes committed based on race, religion, national origin, ethnicity, or gender, allowed same-gender couples to adopt children in some states, struck down laws against sodomy, and finally, in 2015, federally recognized marriage between same-gender couples.

So then, in the half-century between Stonewall and the present day, a broad coalitional social movement has worked to fulfill Rustin’s call for political, moral, and psychological action to create an America where people cannot openly manifest hate. Of course, the struggle to maintain these gains continues, as we highlight throughout this book.

Now, let’s turn our sociological imaginations from public issues to the everyday personal revolutions required to fulfill Rustin’s call for LGBTQIA+ individuals to overcome fear, self-blame, and self-denial.

Coming Out

People who identify themselves as LGBTQIA+ face intense social pressures. There are indeed more legal protections for LGBTQIA+ people than ever before, and more people than ever before accept and embrace LGBTQIA+ people in public life. Yet, as we discuss throughout this book, the civil rights of LGBTQIA+ people are still up for debate in state legislatures, schools, religious institutions, and communities. A powerful and well-organized minority of anti-LGBTQIA+ political activists are working hard to maintain heteronormativity in American culture. How do you think these social pressures impact the process of individual identity formation (Chapter 2)?

A unique aspect of identity formation for people who identify as LGBTQIA+ is coming out. Coming out is a social process of recognizing and sharing sexual orientation and/or gender identity. Coming out is both private and also very public. Because heterosexuality is the norm to which children are routinely socialized, the process of becoming aware that you are not heterosexual and integrating that awareness with identity can be difficult. For people whose families and communities are deeply invested in heteronormativity, coming out can include a risk of relationship loss and social stigmatization. For people who come out to supportive family, friends, and community, coming out can be an affirming process.

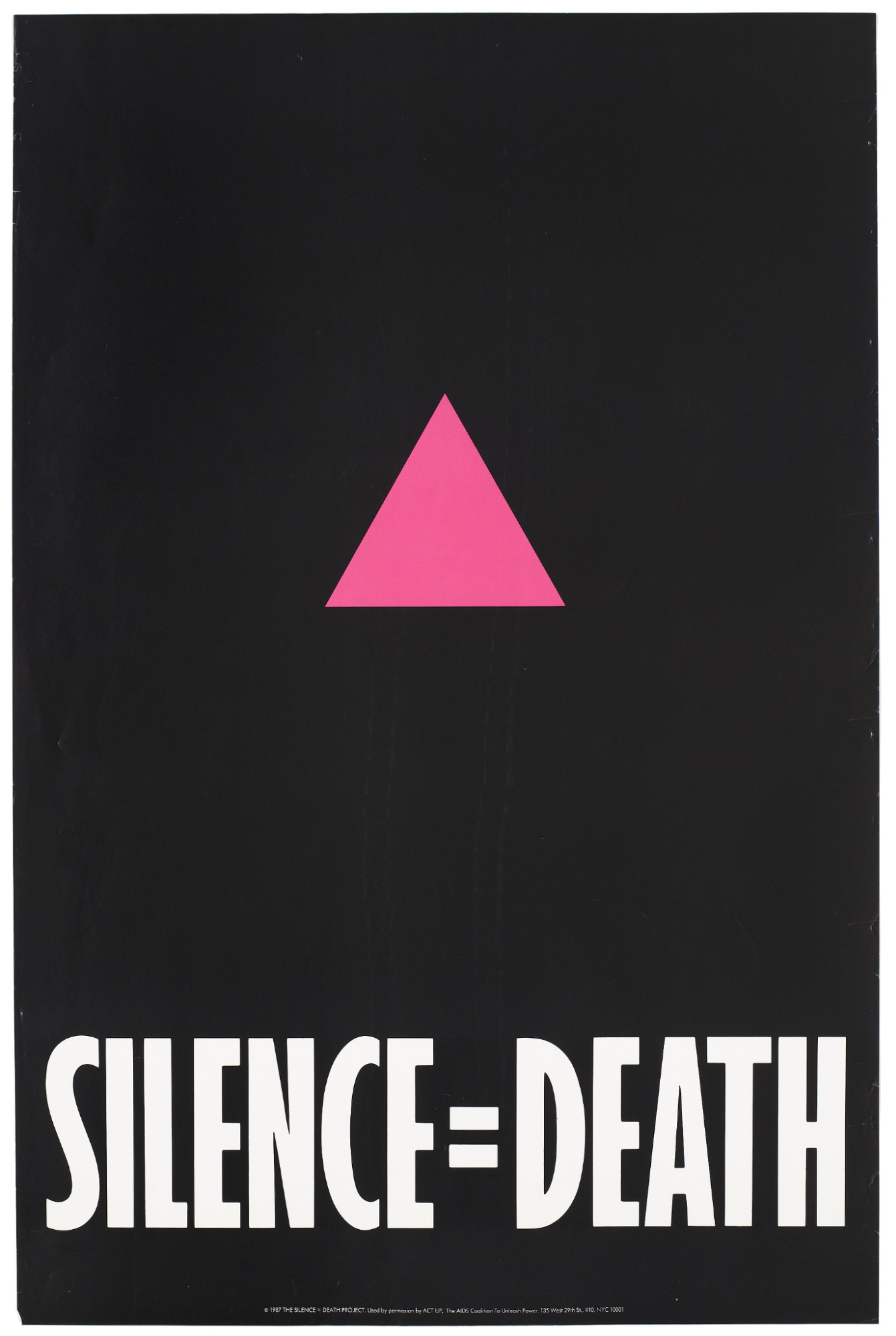

People who do not know they are LGBTQIA+ or know but do not come out publicly are said to be in the closet or closeted. Before the HIV/AIDS crisis, it was much more common for people to be out to a small circle of other LGBTQIA+ people but not out to family, straight friends, or their community. In those days, the closet represented safety. During the early days of the HIV/AIDS Crisis, activists trying to build political will to address the crisis challenged people to come out with the slogan, “silence = death” (figure 3.7). In other words, fear of being known as LGBTQIA+ was preventing people from exercising their political power.

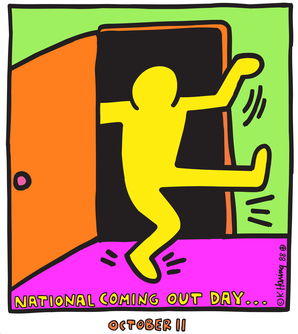

The first National Coming Out Day was organized on October 11, 1988, to create a safe and affirming social environment for as many people as possible to come out and raise the visibility of LGBTQIA+ people. It worked, too. As more people came out, including those who were respected and powerful in popular culture, public opinion about LGBTQIA+ issues began to change. On a more personal level, people who thought they didn’t know anyone who was queer began to realize that they knew and loved LGBTQIA+ people. This awareness made the issues like HIV, workplace discrimination, and hate crimes seem more personal. As Michelle Obama famously observed, “It is harder to hate people close up” (The Late Show 2018). Today, coming out is recognized and celebrated as a right of passage for LGBTQIA+ people, although it is still not a safe process for many people.

Has anyone you know ever come out to you about being LGBTQIA+? What was it like for you? What do you think it was like for them? According to a 2013 Pew Research survey of people who identify as “lesbians, gay men, and bisexuals,” 27% were younger than ten years old when they “first felt they might not be heterosexual.” 59% of respondents were between 10 and 19, and 11% were 20 or older (Pew Research Center 2013). The video in figure 3.9 features people who came out as teens. The video in figure 3.10 features a person coming out later in life. As you watch them, notice that Andy said that he knew he was gay for a long time before he came out. The same Pew Research study found that 43% of respondents did not come out to someone else until they were over 20. In other words, there can be a significant time lapse between coming out to self and publicly coming out.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lhkuYGZyp_o

The public aspect of coming out is not a one-and-done event. Many people describe coming out many times, first to friends, family, and possibly co-workers, and then as disclosing sexual orientation becomes a routine part of establishing a new social relationship. Each disclosure can represent a risk. The social risks associated with coming out can also vary depending on location. For example, people in the western U.S. report much higher rates of acceptance than people in the South and Midwest (Pew Research Center 2013).

Have you ever been to a Pride event? Pride festivals and parades are an extension of the public aspect of coming out that also emerged from the Gay Liberation Movement. These collective coming-out rituals are demonstrations of visibility for LGBTQIA+ people and celebrations of LGBTQIA+ joy, diversity, and solidarity. In this context, pride is not vanity but rather an antidote to the fear, self-blame, and self-denial that Rustin identified.

Gender Identity & Sexual Orientation

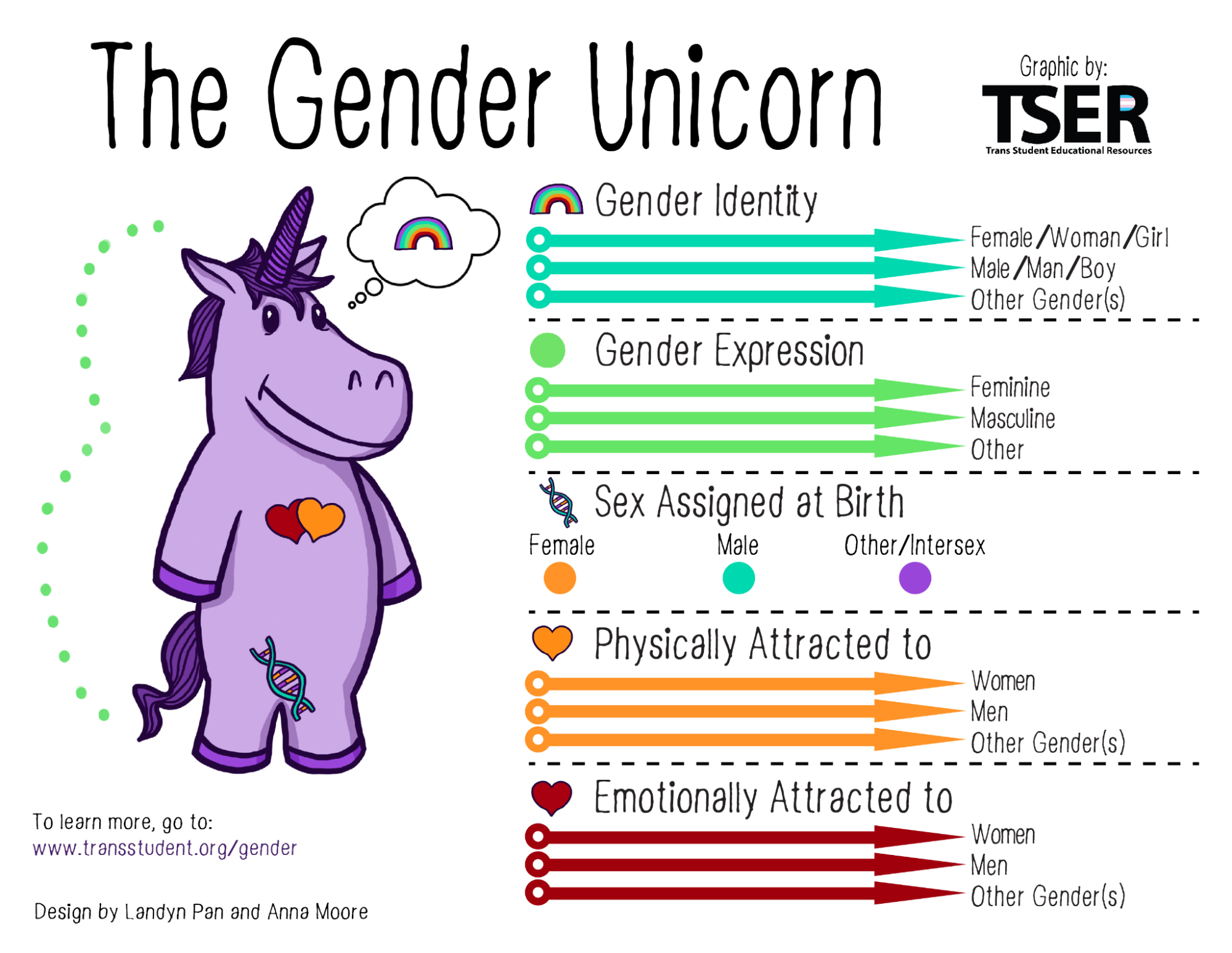

As you have worked through this section about sexual orientation, have you noticed themes that overlap with gender identity and gender expression? For instance, trans, intersex, and non-binary people have similar coming out experiences to those of lesbians, gay men, bisexuals, and queer people. This can be even more complex for people with trans and nonbinary gender identities and queer sexual orientation. This section will use the Gender Unicorn (figure 3.11) to bring together the discussion of gender identity from Chapter 2 with the discussion of sexuality in this chapter to see how identity, expression, sex, and attraction work together to produce a diverse rainbow of individual possibilities beyond the binary patriarchal norms of sexuality and gender.

Recall from Chapter Two that gender identity is the gender we experience ourselves to be. Everyone has a gender identity, including you. Binary construction of gender restricts gender identity to either female/woman/girl or male/man/boy. A more expansive construction of gender allows for the possibility that female, woman, and girl and male, man, and boy are also not necessarily linked to each other but are just six common gender identities. It also recognizes transgender and nonbinary genders, as well as ethnic and culturally specific third genders like Fa’afafine and Two-Spirit (Chapter One).

Recall also from Chapter Two that gender expression is how our gender identity is expressed outwardly through clothing, personal grooming, self-adornment, physical posture and gestures, and other elements of self-presentation. Here again, the binary construction of gender restricts possible gender expression to be either masculine or feminine. Patriarchal gender norms require gender expression to align with gender identity. More expansive nonbinary constructions of gender identity hold space for nonbinary gender expressions that may blend masculine and feminine, elements of self-presentation, or express no discernible gender at all. Nonpatriarchal gender norms hold space for gender expression that may not align with gender identity and also with queer gender identities, like Bears (figure 3.12). Bears are gender expressions specific to gay men that play with traditional masculinity in the form of abundant facial and body hair, large body sizes, and traditionally masculine clothes. Queer gender expressions can also be racially, ethnic, and culturally specific. Drag is an art form that plays with gender expression and gender identity.

LEARN MORE: Queer Gender Expression

To learn more about lesbian masculinity, watch Studs and Butches [Streaming Video].

The final concept from Chapter Two that we will review here is sex assigned at birth. Recall that sex assigned at birth is the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex based on a combination of anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes. While babies born with differences in sexual development, including genetic, hormonal, or anatomical variations, produce atypical sex characteristics, such as chromosomes, gonads, sex hormones, or genitals, who might otherwise be assigned intersex at birth, have historically been assigned either male or female at birth in patriarchal societies, and subject to medically unnecessary genital surgeries which have been shown to have significant physical and psychological risks as children mature. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) opposes medically unnecessary genital surgeries performed on intersex children (AAFP 2023).

Physical attraction is the basis for sexual orientation. Binary heteronormativity demands that people be physically attracted to people of the “opposite gender.” Nonbinary sexuality recognizes that there are no opposite genders, that masculinity and femininity exist within both genders, and that physical attraction exists as a broad spectrum of possibilities. Some people are only attracted to people of the same gender, some are only attracted to a specific gender that is different from their own, others are attracted to people of all genders, and still others do not experience physical attraction to anyone.

Emotional attraction as a category is often overlooked, but it is an important aspect of sexual orientation. Sexual and romantic/emotional attraction can be from a variety of factors, including but not limited to gender identity, gender expression/presentation, and sex assigned at birth or other types of attraction related to gender, such as aesthetical or platonic.

The Gender Unicorn can help describe the ways sexual orientation encompasses gender identity, gender expression, sex assigned at birth, physical attraction, and emotional attraction. Check out the Looking Through the Lens activity at the end of this chapter to use the Gender Unicorn to explore your own multi-dimensional sexual identity.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Who Do You Love?

Open Content, Original

“Who do You Love?” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Who Do You Love? Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 3.7. Image is in the Public Domain, courtesy of the Wellcome Collection.

Figure 3.11. “The Gender Unicorn” by Trans Student Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.12. “Oregon Bears” by Another Believer is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 3.4. “An incomplete list of possible sexual orientations” draws from “The Acronym and Beyond: A Glossary of Terms” in Learning for Justice, Southern Poverty Law Center (2018), and is included under fair use. Modifications by Heidi Esbensen and Nora Karena include selecting terms and definitions for table.

Figure 3.5. “Stonewall riots” by Joseph Ambrosini of the New York Daily News is included under fair use.

Figure 3.6. “She’s Beautiful When She’s Angry” by Bella Black is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.8. “Logo ncod lg” by The Human Rights Campaign, courtesy of Keith Haring, is included under fair use.

Figure 3.9. “Teen Coming Out Stories” by Seventeen is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 3.10. “Coming Out Stories – Andy” by Waverly Care is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

the social enforcement of heterosexuality, in which there are only two genders, that these genders are opposites, and that any sexual activity between people of the same gender is deviant or unnatural.

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to other people; often used to signify the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the gender identities to which a person is most attracted (Learning for Justice 2018).

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior, experience, and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. (Mills 1959)

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

an archaic legal term to describe oral or anal sex, generally between men.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual, Plus a continuously expanding spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations.

an archaic term to describe men who dressed as women or women who dressed as men.

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

a process of coming to understand ourselves and differentiate ourselves in relation to our social world.

a social process of recognizing and sharing sexual orientation and/or gender identity.

people who do not know they are LGBTQIA+ or know but do not come out publicly are said to be in the closet or closeted.

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

the way our gender identity is expressed outwardly through clothing, personal grooming, self-adornment, physical posture and gestures, and other elements of self-presentation.

people with differences in sexual development (DSD) sometimes identify as intersex.

refers to gender identities beyond binary identifications of man or woman/masculine or feminine.

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex based on a combination of anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes.