3.2 Sexuality and the Sociological Imagination

Sex and sexuality have long been a subject of scientific inquiry. Beginning in the early 1800s, research about human sexuality was conducted by physicians, psychiatrists, and criminologists concerned with questions of public health and deviance from social norms (Kinsey Institute 2022). Binary, biologically determined gender was an unquestioned assumption in early sexual research. Feminine sexual autonomy, same-sex attraction, and transgender and non-binary gender expression, once considered moral problems, were pathologized as mental illness.

Beginning in the mid-1900s, and coinciding with a “sexual revolution” that challenged dominant gender norms, social research began to challenge the idea that deviation from socially constructed sexual norms is neither a moral failing nor a mental illness. Recall from Chapter One that C. Wright Mills (he/him) described the sociological imagination as a way of understanding that behavior, which seems like an individual choice or problem, can be understood as the result of social and cultural influences. As you work through this section, use your sociological imagination to think about how sexual norms are socially constructed and understood.

Early Research: What is Normal?

In the 1930s, the zoologist Alfred Kinsey (he/him) began teaching an interdisciplinary course for married students about human sexuality. His students frequently confided in him about details about their own sexual experiences and then asked a common question, “Am I normal?” Around the same time, he delivered a lecture to a faculty discussion group where he attacked the “widespread ignorance of sexual structure and physiology,” and he argued that waiting to engage in sexual activity until marriage was psychologically harmful. This lecture, along with his students’ earnest disclosures, inspired research that documented the actual lived sexual experiences of research participants. Kinsey’s findings were published in two books, Sexual Behavior in the Human Male (1948) and Sexual Behavior in the Human Female (1953), known collectively as the Kinsey Reports (Kinsey Institute 2022).

Kinsey shed new light on the sexual behavior and the physical sexual characteristics of the respondents. For example, Kinsey found that married women in their late teens reported having sex an average of 2.8 times per week; for women at age 30, frequency fell to 2.2; and by age 50, married women reported only having sex once a week. He also found between 10% and 16% of married women aged 26 to 50 were engaged in extramarital sex. Based on his research, Kinsey also estimated that about half of all married men had some extramarital sexual experience at some point in their married lives. Kinsey contributed to and documented changes in sexual norms from the 1930s to the 1980s, including the increased acceptance of sex outside of marriage and increased acceptance of homosexuality. Today, the Kinsey Institute at Indiana University continues to produce research on sex and sexuality.

Clelia Duel Mosher (she/her), a medical doctor and professor at Stanford, studied women’s sexual health and advocated for a better understanding of menstrual hygiene and against corsets. Decades before Kinsey’s well-funded work, Mosher compiled the Statistical Study Of The Marriage Of Forty-Seven Women. This first known survey of women’s beliefs about and experiences of sex included questions about pleasure, contraception, frequency of sex, and subjective importance of sex (Landale & Guest 1986). Mosher never published the survey, which was forgotten until 1973, and then finally published in 1980. Because her surveys were collected between 1892 and 1920, they offer insight into shifting social understanding of sex, marriage, and feminine pleasure in post-victorian culture (Seidmen 1989).

While neither Mosher nor Kinsey were social scientists, their research methods relied on structured interviews to collect qualitative data (Chapter One) describing individual experiences, understanding, and opinions about sexuality. They are important examples of researchers who engaged a sociological imagination to understand individual experiences within specific social contexts. But how do actual sociologists approach the study of sex and sexuality?

Real But Not True: Sex Outside of Marriage

Let’s consider how what you are learning about sex outside of marriage demonstrates that sexual norms are socially constructed (not true) and have real-life consequences (real).

The tools of sociology include:

- Sociological Imagination

- Research-based Evidence

- Social Theory

Gender conflict theory analyzes how economic gender inequality supports patriarchal power structures in the workplace and the marketplace.

A feminist theoretical perspective of the gender wage gap helps us see how systems of power like patriarchy create the social conditions that lead to gender-based income inequality.

We can recognize that socially social norms against sex outside of marriage are not universally true when we can demonstrate that they:

- Change over time

- Are not the same in all societies

- Are imposed, enforced, reproduced, negotiated, or challenged through social interactions.

Having identified that social norms against sex outside of marriage do not align with the lived experience of so many people, we can look at how these norms are socially constructed:

- Laws and customs

- Religious teachings

- Literature and Stories

- Popular music and entertainment

- Education

- Family

Sexual norms have changed over time.

- A majority of Americans currently believe that sex before marriage is socially acceptable. This was not true when Kinsey started his research.

The real social consequences of the social norms that stigmatize sex outside of marriage:

- People have believed that they were sexually deviant because their sexual experiences were outside of accepted norms.

- Early social scientists relied on these norms to create scientific theories of deviance that further stigmatized people whose lived experiences did not align with accepted norms.

- Most states have had laws against sex outside of marriage at some point in U.S. History. 16 states still do, although they are rarely enforced.

As you continue to work through this book, be on the lookout for other examples of socially constructed meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences and for the ways that tools of sociology can be used to reveal them as social constructions that are not universally true, but have real consequences.

Sexual Scripts

One line of sociological inquiry involves the study of how culture is socially created and reproduced in social interactions. You will learn more about social interactionist theories in Chapter Four. For now, let’s see how this works with sexual scripts. A script is what actors read or study to guide their behavior and dialog in certain roles. It teaches them what to do and say in order to perform their role. Similarly, sexual scripts are socially constructed blueprints for sexual expression, sexual orientation, sexual behaviors, and sexual desires that guide our performance of sexuality.

We are not born with sexual scripts in place. They are socially constructed through a process of sexual socialization, in which we learn how, when, where, with whom, why, and what motivates us as sexual beings. Sexual scripts, once learned, shape how we answer our biological drives. Many of us learn our sexual scripts passively as we synthesize concepts, images, ideals, and—sometimes—misconceptions.

Sexual scripts carry our shared understandings about sexual behavior and are highly gendered. In other words, men and women have specific parts to play in many commonly understood sexual scripts because sexuality is also a way of constructing gender. For example, the commonly-held belief that men are stronger, courser, more active, and more aggressive while women are weaker, softer, more passive, and more submissive in sexual relationships supports binary sexual scripts about gendered dominance and submission. These scripts rest on an assumption that men and women are opposites. They are encoded in some religious messages, health education, and popular culture.

There are three levels of sexual scripts: cultural, interpersonal, and psychological. Laura Carpenter (she/her), analyzed cultural-level sexual scripts in 244 articles published between 1974 and 1994 in the teen magazine, Seventeen. The articles discussed a broad range of controversial sexual topics of interest to young women. Carpenter found that “Sexual scripts in popular media may have profound real-life effects” and that articles favoring traditional sexual scripts “may discourage challenges to the sexual and gender status quo” (Carpenter 1998).

Many sexual scripts that dominate patriarchal cultures depend on commonly held, socially constructed assumptions like “men should be in charge of sex,” “women should not enjoy sex or express their desire for it,” “men are more sexual than women,” “all sex leads to orgasm.” These assumptions can undermine intimacy between sexual partners because people experience sexual desire differently. For example, women who desire sex and are sexually aggressive or men who do not experience sexual attraction or do not have a desire for sex are set up to be shamed. More positive sexual scripts encourage sexual partners to take ownership of their sexual experiences, communicate openly and honestly about their feelings, and learn to meet one another’s desires and needs while ensuring their desires and needs are also met.

LEARN MORE: Racialized Sexual Scripts

Learn more about how sexual scripts are also racialized in this awesome blog from Black Feminisms [Website].

Pleasure, Work, and Power

Have you ever noticed that social norms about sexuality are often dependent on the relationship in which a sex act is performed? A consensual sex act between two people in a committed relationship or two single people is generally considered socially acceptable. However, the same consensual act between more than two people or between a partnered person and a single person is considered less acceptable. When the same sex act is exchanged for money or other goods, it is even less acceptable. Similarly, a significant portion of people in the U.S. still believe that sex between people of the same gender is not acceptable (Brenan 2024). While we often refer to sex as a private issue, it has very public consequences for people who transgress sexual norms and rewards for people who uphold them.

In this section, we will apply our sociological imaginations to orgasms, sex work, and monogamy, three topics related to sexuality, gender, and power. Since sexuality is an aspect of relationships, this section will also touch on various forms of intimacy in the context of different relationships. As you work through this section, look for examples of how gender, sexuality, and power are socially constructed, contested, or enforced.

Orgasms

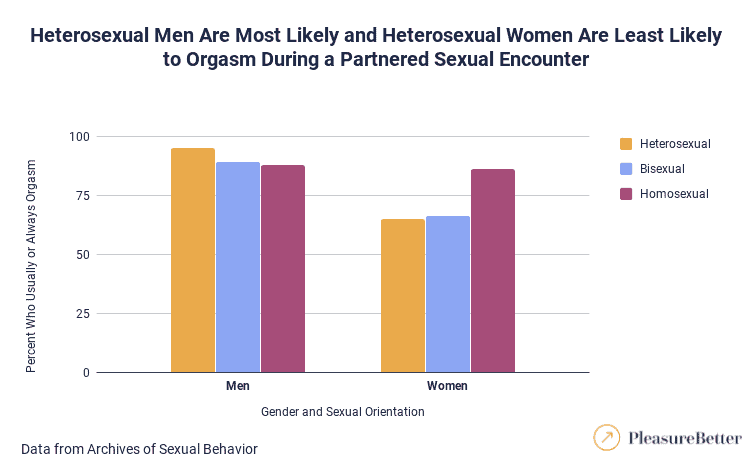

The orgasm gap is the difference between male-reported orgasms and female-reported orgasms. According to data from the National Survey of Sexual Health and Behavior from 2018, 91% of men reported they had an orgasm at their most recent sexual event. Yet, only 64% of women reported an orgasm at their most recent sexual event, as you see in figure 3.3 (Townes, et. al. 2022). Men of the three different sexual identities are more likely to orgasm and experience more orgasms in heterosexual relationships.

The double standard relates to women’s willing participation in and enjoyment of sexual acts. They should desire sex but not appear too willing. Women should also “fulfill” the desires of their male sexual partners with minimal focus on their own pleasures. Sex is for men to enjoy and women to participate in for their partner’s pleasure. The sexual scripts enacted in patriarchal society teach women to focus on pleasing men and men on pleasing themselves.

Women who orgasm more in intimate relations receive more oral sex, have longer sexual encounters, are more satisfied within the relationship, speak up about what they want, and routinely have sexual encounters that include more elements of intimacy, like kissing, build-up, and manual stimulation (Frederick et al. 2017).

Do people in LGBTQIA+ relationships experience an orgasm gap? Figure 3.3 shows that heterosexual men usually or always orgasm during sex (95%). Gay men (89%), bisexual men (88%), and lesbian women (86%) stated high rates of orgasm while being sexually intimate. Bisexual women and heterosexual women fall short with 66% and 65%, respectively.

Sex Work

Sex work, sex workers, and their patrons have also been a popular topic of sociological research. Sex workers are adults who receive money or goods in exchange for consensual sexual services or erotic performances, either regularly or occasionally (Open Society Foundations 2019). The term “sex worker” is preferred over the more stigmatized term “prostitute” because it acknowledges that sex work is a form of labor that encompasses a range of activities beyond having sex with strangers for cash. Sex work can also include exotic dancing, phone and internet sex, and performing in live or filmed pornography. Sociologists Kari Larum (she/her) and Barb Brents (she/her) have studied sex and sex work from a feminist perspective and identified several subtopics of scholarship about sex work, including “bodily and emotional labor, criminal justice, citizenship, culture, discourse analysis, gender, globalization, (im)migration, organizations, politics, religion, sexuality, and social movements” (Lerum & Brents 2016).

Sociologists also consider how the legal and cultural marginalization makes sex workers especially vulnerable to exploitation and forced labor. Larum and Brents identify how bias against sex work contributes to the rise of the “rescue industry,” which generates moral panic by reframing all sex work as “sex trafficking” and all sex workers as either sex traffickers or victims to generate funding for more policing of communities that are vulnerable to exploitation and social services to “rescue” and rehabilitate sex workers.

In contrast, the feminist sociologist Crystal A. Jackson has documented how sex workers organize to create networks of care and resistance. Jackson’s research at the 2010 Desiree Alliance conference, a conference by and for sex workers, identified peer-to-peer skill sharing as a means to build safety and resilience in a hostile and dangerous working environment (Jackson 2019). This peer-based strategy echoes many other social movements led by oppressed people.

Monogamy

In contrast to the lived reality documented by Kinsey and other researchers, social norms surrounding sexuality in the U.S. have traditionally favored heterosexual monogamous sex between married partners over premarital sex, extramarital sex, and sex between people of the same gender. Monogamy is the practice of having one intimate partner at a time. Some sociologists have stressed the importance of regulating sexual behavior to ensure marital cohesion and family stability, arguing that sexual activity in the confines of monogamous marriage serves to intensify the bond between spouses and to ensure that procreation occurs within a stable, legally recognized relationship. As monogamous same-sex intimate partnerships have become normalized, a growing body of evidence shows that positive psychosocial development is not dependent on whether parents are straight, lesbian, or gay, but the quality of parents’ relationship with each other is determinative (Wainright et al. 2004).

The sexual revolution of the 60s and 70s saw a shift in social norms around premarital sex that has been attributed to an increase in women’s sexual autonomy. A 1983 study of 49 sex manuals published between 1950 and 1980 to determine if recent changes in social gender norms for women have influenced sexual scripts in sex and marriage manuals for heterosexual couples. This research found a clear shift from a model of women’s sexuality that emphasizes gender difference and inequality to a model that prioritizes women’s sexual autonomy. The study identifies new sexual scripts that reframe a woman’s premarital sexual experience, including lesbian and bisexual experiences, as positive (Weinberg et al. 1983). Women empowered to take responsibility for their own sexual pleasure and satisfaction are no longer deviant. They are the norm.

Social norms against sexual infidelity in monogamous marriages have been more constant. A 2023 Gallup Poll (2023) found that only 22% of respondents believed that it is unacceptable for unmarried people to have sex, but 88% believe that it is unacceptable for married people who have sex with someone outside of marriage (Jones 2023). A 2020 study theorized the reason for this may be found in the meaning we attach to sex in a committed partnership, in which sexual fidelity is a marker of trust, and sexual infidelity signals more generalized untrustworthiness (Belleau et al. 2020).

Feminists and queer theorists also explore relationships between sexuality and power. For example, the book Questioning the Couple Form explores a historically feminist critique of the cultural dominance of families built on “the romantic love, couple-based form” and documents emerging alternative forms of intimate relationships and family building (Roseneil et al. 2020).

Check out LEARN MORE: Polyamory, Monogamy and Power in the box below for an example of how Mimi Schippers (she/her) researches non-monogamy from a sociological perspective in her book, Polyamory, Monogamy, and American Dreams: The Stories We Tell about Poly Lives and the Cultural Production of Inequality (2020).

Various forms of polyamory have always existed in human societies. Polyamory is the practice of having multiple intimate partners. One form of polyamory includes polygamy, the practice of one man having multiple intimate partners at the same time, which is a norm in many cultures around the world. Polyandry is the practice of one woman having multiple intimate partners at the same time, which is less common but has been a dominant practice in some societies. Sociologists explore various forms of sexual partnership and the social conditions that favor certain forms.

As polyamory has become more visible, some people have begun describing their sexuality, not only in terms of who they are sexually attracted to, as we will discuss in the next section, but also in terms of their preferred partnership forms, such as being polyamorous or monogamous.

LEARN MORE: Polyamory, Monogamy and Power

Watch Polyamory, Monogamy, and American Dreams: The Stories We Tell About Poly Lives and the Cultural Production of Inequality [Streaming Video] to learn more about how sociologists approach topics like polyamory, monogamy, and power.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Sex and the Sociological Imagination

Open Content, Original

“Sexuality and the Sociological Imagination” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Orgasms” by Heidi Ebensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Real But Not True Puzzle Images” by Nora Karena and Katie Losier are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Sexuality and the Sociological Imagination Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Sexual Scripts” is adapted from “5.1: Sexual Scripts” by Garrett Rieck & Justin Lundin, Introduction to Health, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Heidi Esbensen and Nora Karena.

Figure 3.2. “Clelia Duel Mosher, 1892” is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Sex worker” definition by Open Society Foundation (2019) is included under fair use.

Figure 3.3. “Heterosexual Men Are Most Likely and Heterosexual Women Are Least Likely to Orgasm During a Partnered Sexual Encounter” by Kate Williams, PleasureBetter, is included under fair use.

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

the way our gender identity is expressed outwardly through clothing, personal grooming, self-adornment, physical posture and gestures, and other elements of self-presentation.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior, experience, and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. (Mills 1959)

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

is a macro-level theory that proposes conflict is a basic fact of social life, which argues that the institutions of society benefit the powerful.

the unequal distribution of power and resources based on gender.

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

literally the rule of fathers. A patriarchal society is one where characteristics associated with masculinity signify more power and status than those associated with femininity.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

socially constructed blueprints for sexual expression, sexual orientation, sexual behaviors, and sexual desires that guide our performance of sexuality.

emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to other people; often used to signify the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the gender identities to which a person is most attracted (Learning for Justice 2018).

the process of learning culture through social interactions.

the practice of having one intimate partner at a time.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual, Plus a continuously expanding spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations.

adults who receive money or goods in exchange for consensual sexual services or erotic performances, either regularly or occasionally (Open Society Foundations 2019).

to describe work that requires managing personal emotions and the emotions of other people (Hochschild, 1983)

purposeful, organized groups that strive to work toward a common social goal.

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Chandler & Munday, 2011).

the practice of having multiple intimate partners.

the practice of one man having multiple intimate partners at the same time.

the practice of one woman having multiple intimate partners at the same time.