3.4 Sexual Violence and Patriarchy

Sex crimes are a category of sexual violence. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), “Sexual violence is any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion, by any person regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting” (WHO 2022).

Sex crimes in the U.S. are punished by imprisonment and social censure. People who are convicted of sex crimes are required to register on a publicly available database of convicted sex offenders and are barred from working with or living near vulnerable people. In 2022, congress re-authorised the 1994 Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) and allocated 700 million dollars to combat gender-based violence, including sexual assault. VAWA funding supports sexual violence response units in local law enforcement agencies, a national network of rape crisis programs that support survivors of sex crimes, as well as prevention programs that aim to reduce the risk of sex crimes. In spite of the strong social sanctions against perpetrators of sex crimes, and the allocation of significant public resources to punishing them, rates of sex crimes have not decreased (see the statistics in the box below).

Select Sexual Violence Statistics from The National Sexual Assault Resource Center (NSARC).

- One in five women and one in seventy-one men will be raped at some point in their lives.

- 47% of all transgender people have been sexually assaulted at some point in their lives, and these rates are even higher for trans People of the Global Majority and people who have done sex work, been homeless, or have (or had) a disability.

- 46.4% of lesbians, 74.9% of bisexual women, and 43.3% of heterosexual women reported sexual violence other than rape during their lifetimes, while 40.2% of gay men, 47.4% of bisexual men, and 20.8% of heterosexual men reported sexual violence other than rape during their lifetimes.

- Nearly one in ten women have been raped by an intimate partner in her lifetime, including completed forced penetration, attempted forced penetration, or alcohol/drug-facilitated completed penetration.

- Approximately one in forty-five men has been made to penetrate an intimate partner during his lifetime.

- In eight out of ten cases of rape, the victim knew the person who sexually assaulted them.

- 8% of rapes occur while the victim is at work.

It has been 30 years since Congress passed the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA), yet sexual violence is still widespread in our community. What do you think it will take to end sexual violence?

In this section, we will apply our sociological imagination to better understand the relationship between sexual violence and patriarchy. As you work through this section, please practice self-care. Your instructor and the school student services team are available to help if you need support around this challenging topic.

Sexual Violence as a Social Problem

Recall that the sociological imagination looks for connections between public issues and personal experiences (Chapter One). Many forms of sexual violence are perpetrated by individuals against other individuals in their families or communities. Individuals who commit sexual crimes are punished by state or federal legal systems because these crimes are also considered crimes against society. Sexual violence does individual harm, but it also harms families and communities. Surviving and recovering from sexual violence is a deeply personal process that also requires social support from family, community, mental health and medical professionals, and other survivors.

Because sexual violence impacts both individuals and society, we can say that it is a social problem. Sociology professor and author Anna Leon-Guerrero (she/her) (figure 3.13) defines a social problem as “a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world” (Leon-Guerrero, 2019, p. 4).

When you think about the current issues facing our society and our planet, you might name war, addiction, climate change, homelessness, or the global pandemic as social problems. You would be mostly right. However, sociologists need to be more specific than that. Because they are trying to explain what social problems are or how to fix them, they need a much more precise definition. To talk effectively about social problems, we must understand five important dimensions of a social problem:

- A social problem goes beyond the experience of an individual.

- A social problem must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action.

- A social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality.

- A social problem results from a conflict in values.

- A social problem is socially constructed but real in its consequences.

We have already established the first two of these points, that sexual violence goes beyond the experience of individuals and that sexual violence must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action. There is abundant evidence that groups of people experience sexual violence unequally.

While sexual violence happens to people of all genders, sexual orientations, and racial identities, women experience higher rates of sexual violence than men. Transgender people experience higher rates of sexual violence than cisgender people. Lesbian, gay, and bisexual people experience higher rates than heterosexual people.

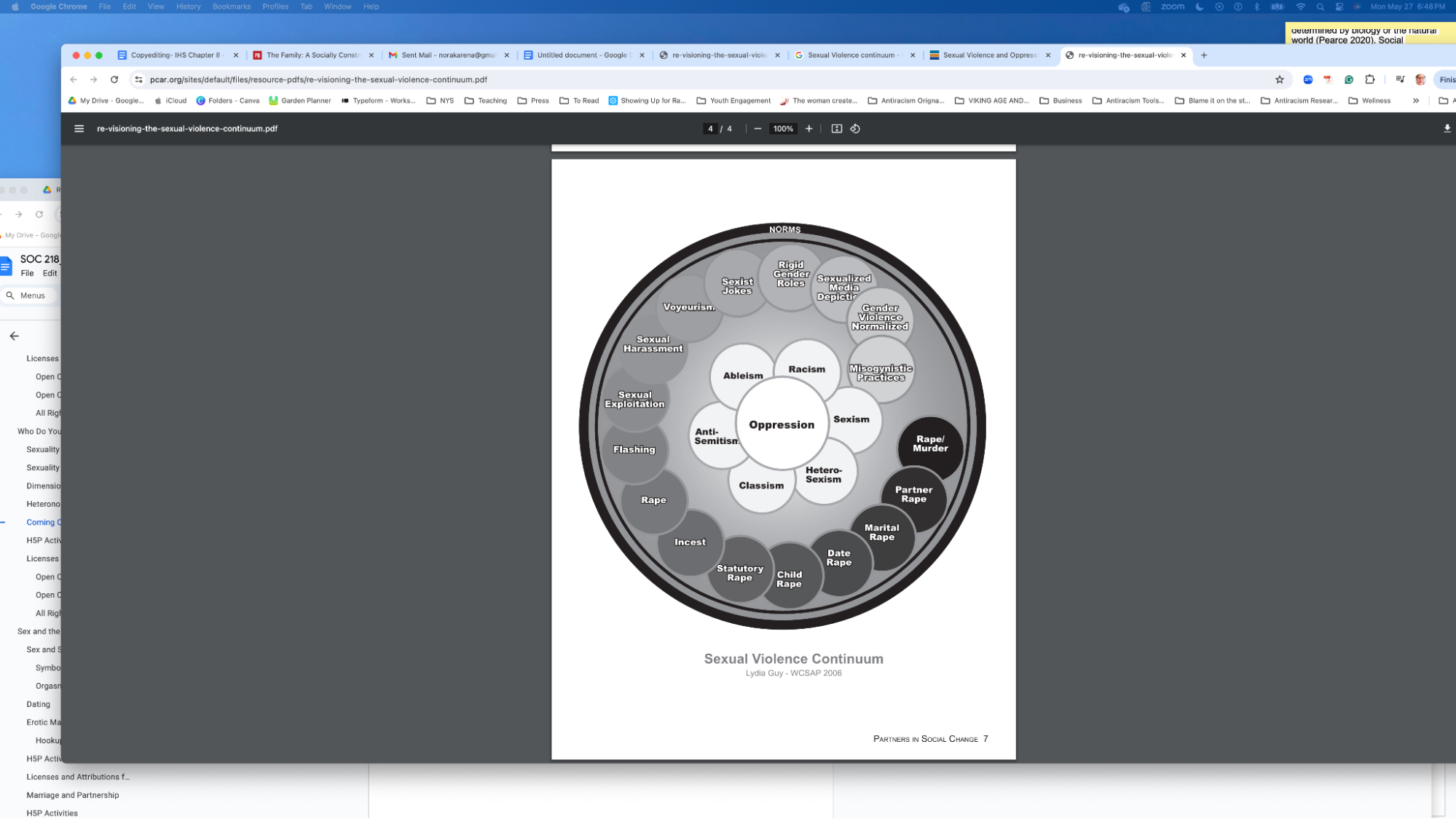

Returning to the statistics from The National Sexual Assault Resource Center, we see that the people most likely to experience sexual violence are trans People of the Global Majority and those who have done sex work, been homeless, or have (or had) a disability (National Sexual Resource Center 2019). But can we claim that sexual violence results from a conflict in values or that it is socially constructed? To answer these questions, let’s look at the continuum of sexual violence (figure 3.14).

The Sexual Violence Continuum

A continuum is a whole phenomenon divided by progressive units that increase in value. For example, a number line from one to ten is a continuum in which the line is the whole, and the numbers that progress in value from one to ten are the units that make up the whole. So whether the value is one, seven, or ten, each numbered value is a part of the whole continuum. Can you think of another example of a continuum?

In the sexual violence continuum (figure 3.14), the progressive units are overlapping circles that represent forms of sexual violence. In the outermost circles are acts of commonly recognized forms of sexual violence, which are legally referred to as sexual assault. Sexual assault is a broad category of non-consensual sexual contact that includes various forms of rape and other illegal sexual contact. Rape is defined as non-consensual oral, anal, or vaginal penetration. Other forms of unwanted sexual contact without penetration include flashing (indecent exposure), voyeurism (watching someone engage in private sexual or intimate behavior), sexual exploitation (sex trafficking), and sexual harassment. Most of these forms of sexual violence are punishable by criminal or civil penalties.

The lighter grey units are forms of sexual violence that are not usually punished by criminal or civil penalties and include sexist jokes, rigid gender roles, sexually violent media (film, books, and music), normalized gender-based violence (trans bashing, intimate partner violence), and misogynistic practices. Misogyny is hatred of, aversion to, or prejudice against women (Merriam-Webster n.d.). The white units that spiral into the continuum’s center represent unequal power and oppression systems. We will learn more about unequal systems of power in Chapter Five. The background of the continuum represents patriarchal society, and the outer ring, labeled “norms,” represents the socially constructed social norms that hold the continuum of sexual violence in place.

The sexual violence continuum helps us think about sexual violence as more than individual acts. Sexual violence is a socially constructed set of individual expressions of power and systems of power based on sexual norms within a patriarchal society. It also helps to understand that ending sexual violence requires more than punishing individual acts, but as our definition of social problems suggests, it must be addressed interdependently, with both individual agency and collective action.

Recent efforts to change social norms about consent are a powerful example of how collective effort, together with individual agency, can reduce sexual violence.

Have you ever heard of affirmative consent? Affirmative consent is consent given for each sex act each time. It’s a powerful idea that seems like it should not be as new as it is. Recall that sexual assault is defined as non-consensual sexual activity. Consensual sexual activity is activity that both (or all) partners fully agree to. Seems simple enough, right? Sometimes, people assume that they have consent because their partner has granted consent before, but that can be a problem because people’s boundaries can change within the moment and over time. Simply because someone agreed to a sexual act one time doesn’t mean they consent to future acts. Affirmative consent is the basis for a healthy and happy sexual relationship and a powerful practice to help survivors of sexual violence recover their sense of sexual agency. It is also a powerful way to help young people be less vulnerable to sexual violence.

When a person assumes they have consent, but they do not, they are committing sexual violence. Check out the short video in figure 3.15 that uses the example of tea to describe many of the circumstances where consent is often assumed.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pZwvrxVavnQ

A Social-Ecological Approach to Preventing Sexual Violence

In the early days of sexual violence response and prevention, beginning in the 1970s, prevention efforts focused on teaching women how to defend against sexual assault and teaching children about safe touch and unsafe touch. These are both important strategies, but they place all of the responsibility for ending sexual violence on people most vulnerable to being assaulted. In recent years, prevention efforts have shifted to prevention efforts that identify risk and protective factors for sexual violence and then develop programs that reduce risk factors and increase protective factors.

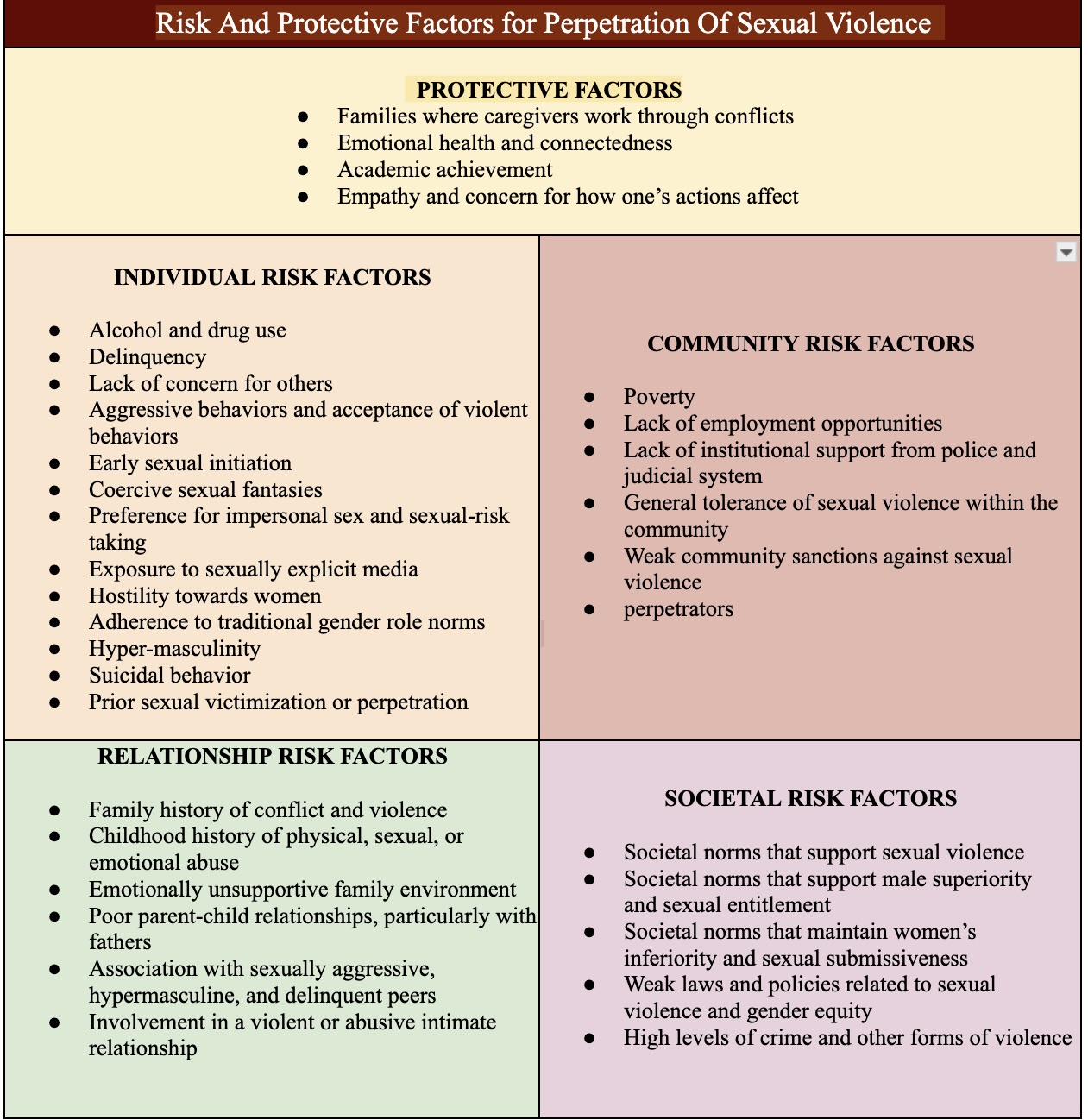

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has identified risk factors that are linked to a greater likelihood of someone committing sexual violence (SV) perpetration and protective factors that may prevent someone from committing sexual violence (figure 3.16). This is not to say that people who experience these factors are destined to commit sexual violence. However, there is an established link between these factors and people who commit sexual violence (CDC n.d.).

Try this thought experiment: After reviewing the risk and protective factors in figure 3.16, imagine a society with fewer risk factors and more protective factors. How would you describe such a community? What would the relationships between people be like? What would the schools and social institutions be like?

For an example of how one community is applying this prevention model, let’s look at The New York City Alliance Against Sexual Assault. After identifying specific risk factors at nightlife venues, like bars, clubs, and restaurants, they developed OutsmartNYC, which conducts community education workshops at nightlife venues in the city on topics of sexual violence prevention, bystander intervention, recognizing and addressing identity-based harm, conflict resolution, de-escalation techniques. The program also hosts monthly collective meetings for people in the nightlife industry to identify and address risk and protective factors. This kind of programming represents a more holistic response to the entire continuum of sexual violence.

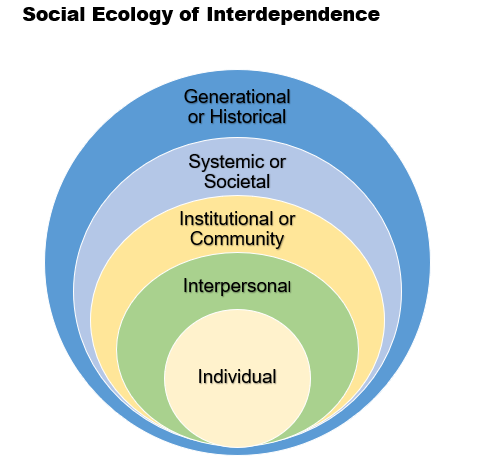

This community-level prevention is based on Ecological Systems Theory, which describes the social world as a layered system in which each layer is a set of social domains that impact the individual. The system moves from the smallest level of the individual to the layer of family through growing layers until it reaches institutions, society, and even historical context. If you compare the continuum of sexual violence to the social-ecosystem model in Figure 3.17, you can see that some forms of sexual violence occur at the interpersonal level, and others occur at community, societal, and historical levels.

For example, normalized gender-based violence has its roots in our shared history and exists at the societal level as shared gender norms, like the idea that boys are more naturally more aggressive than girls, at the community level that treats boys and girls differently when they are aggressive, and at the interpersonal level in the form of violence.

LEARN MORE: Ecological Systems Theory

You can learn more about the development of ecological systems theory by watching Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems: 5 Forces Impacting Our Lives [Streaming Video].

Let’s Review

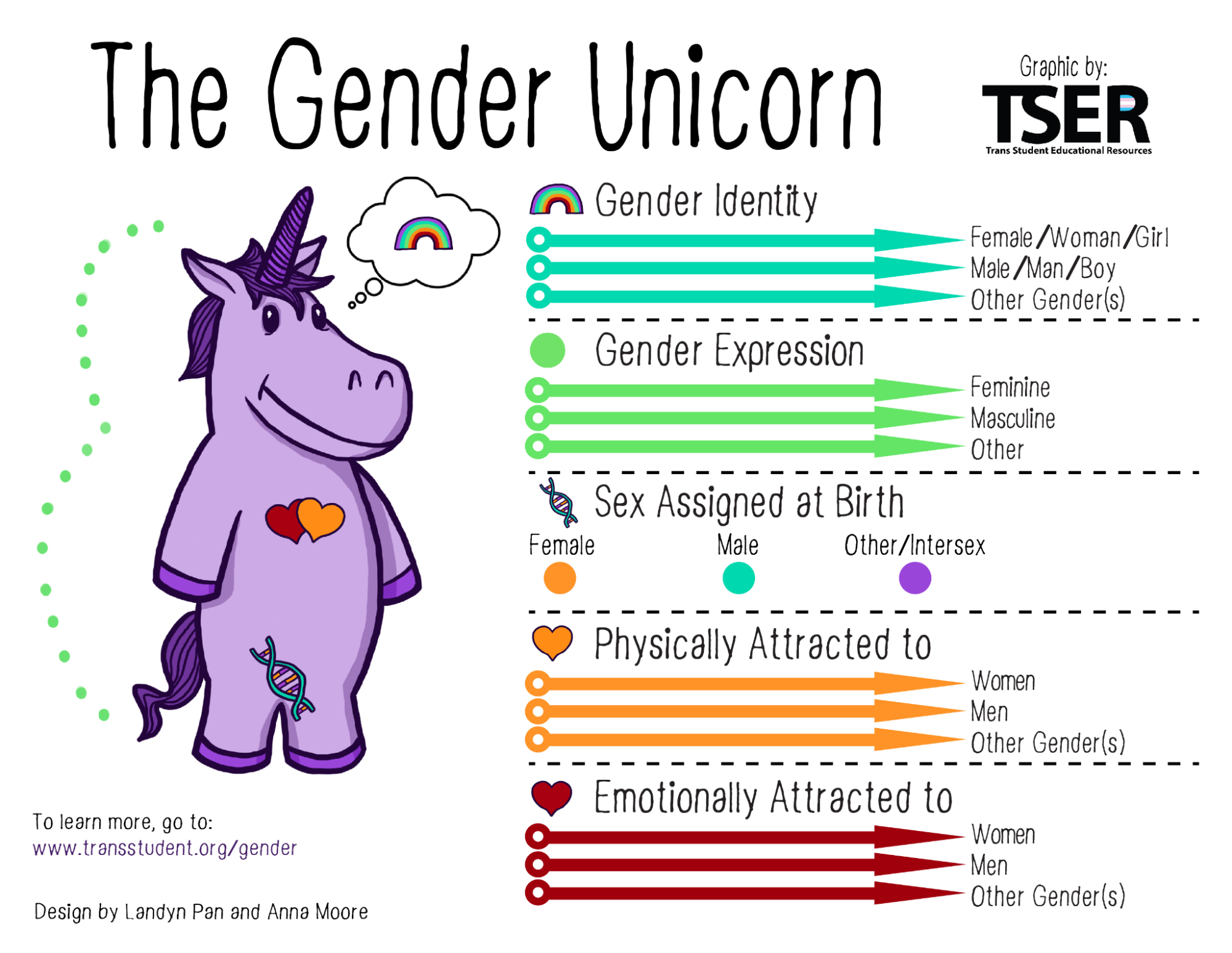

Looking Through the Lens: The Gender Unicorn

In this activity, we will use continuums of gender expression, gender identity, sex assigned at birth, and sexual orientation to explore the expansive spectrum of human sexualities. Note: You do not have to share the results with anyone unless you want to, but your professor might ask you to confirm that you completed the activity.

Step 1:

- What is your gender identity?

- Describe your gender expression.

- What is your sex assigned at birth?

- Who are you physically attracted to?

- Who are you emotionally attracted to?

Step 2:

Option 1: Write a short paragraph or more about how this reflexive exercise helps you understand the expansive spectrum of human sexualities?

Option 2: Create a drawing or collage to represent how this reflexive exercise helps you understand the expansive spectrum of human sexualities.

Licenses and Attributions for Sexual Violence and Patriarchy

Open Content, Original

“Sexual Violence and Patriarchy” by Nora Karena and Heidi Ebensen is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Looking Through The Lens: The Gender Unicorn” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Sexual Violence and Patriarchy Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Sexual Violence as a Social Problem” is adapted from “What is a social problem?” by Kimberly Puttman in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena including editing and remixing for length and context.

Figure 3.16. “Risk and Protective Factors for Perpetration of Sexual Violence” is adapted by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0. It is adapted from Risk and Protective Factors by the Centers for Disease Control, which is in the Public Domain.

Figure 3.17. “Social Ecosystem Model” by Kimberly Puttman from Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 3.18. “The Gender Unicorn” by Trans Student Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Social problem” definition from Leon-Guerrero (2019) is included under fair use.

“Sexual violence” definition from WHO (2022) is included under fair use.

“Misogyny” definition from Merriam-Webster (n.d.) is included under fair use.

“Select Sexual Violence Statistics from The National Sexual Assault Resource Center” is adapted from “Sexual Violence & Transgender/Non-Binary Communities” and “Statistics About Sexual Violence” by the The National Sexual Assault Resource Center, included under fair use.

Figure 3.13. Photo of Dr. Anna Leon-Guerrero by Pacific Lutheran University is included with permission.

Figure 3.14. “The Sexual Violence Continuum” by Lydia Guy is included under fair use.

Figure 3.15. “Tea and Consent” by Thames Valley Police is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

any sexual act, attempt to obtain a sexual act, or other act directed against a person’s sexuality using coercion by any person, regardless of their relationship to the victim, in any setting (WHO 2022).

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

a broad category of non-consensual sexual contact that includes various forms of rape and other illegal sexual contact.

non-consensual oral, anal, or vaginal penetration.

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior, experience, and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. (Mills 1959)

literally the rule of fathers. A patriarchal society is one where characteristics associated with masculinity signify more power and status than those associated with femininity.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world (Guerrero 20164).

describes people who identify as the same gender they were assigned at birth.

hatred of, aversion to, or prejudice against women (Merriam-Webster, n.d.).

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

consent given for each sex act each time.

a theory that describes the social world as a layered system, in which each layer is a set of social domains that impact the individual. The system moves from the smallest level of the individual to the layer of family, through growing layers until it reaches institutions, society, and even historical context.

the way our gender identity is expressed outwardly through clothing, personal grooming, self-adornment, physical posture and gestures, and other elements of self-presentation.

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex based on a combination of anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes.

emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to other people; often used to signify the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the gender identities to which a person is most attracted (Learning for Justice 2018).