4.3 Feminist Activism and Theory

Return for a moment to Figure 4.1. Recall that the women of SWS protested the lack of women in teaching, research, and leadership within sociology. Why do you think having professors who are women, LGBTQIA+, or People of the Global Majority is important? Can’t people learn just as well from white men? Feminist scholars and activists argue that the sexism and racism that made it seem normal to exclude women, people who identify as LGBTQIA+, and PGM from full participation in teaching, research, and leadership also influenced what could be taught, what research questions could be asked, and what counted as legitimate sociological knowledge.

Standpoint theory argues that knowledge is socially situated and that the dominant standpoint of social and natural sciences has been based on “rampant sexism and androcentrism (centering men)” (Harding 1992). Standpoint methodology seeks out and includes the lived experience and perspectives that make up the socially situated knowledge of people who have been marginalized by sexist and androcentric research. For example, transgender black women carry specific knowledge of their own social context, and that knowledge is critical for the research and theory that impacts them to be accurate and truly objective.

Standpoint theory is a foundational feminist theory and methodology developed in the 1970s by the feminist philosopher Sandra Harding (she/her) (figure 4.6) and further developed by feminist researchers in sociology, including Dorothy Smith (she/her) and Patricia Hill Collins (she/her) and in gender studies more broadly.

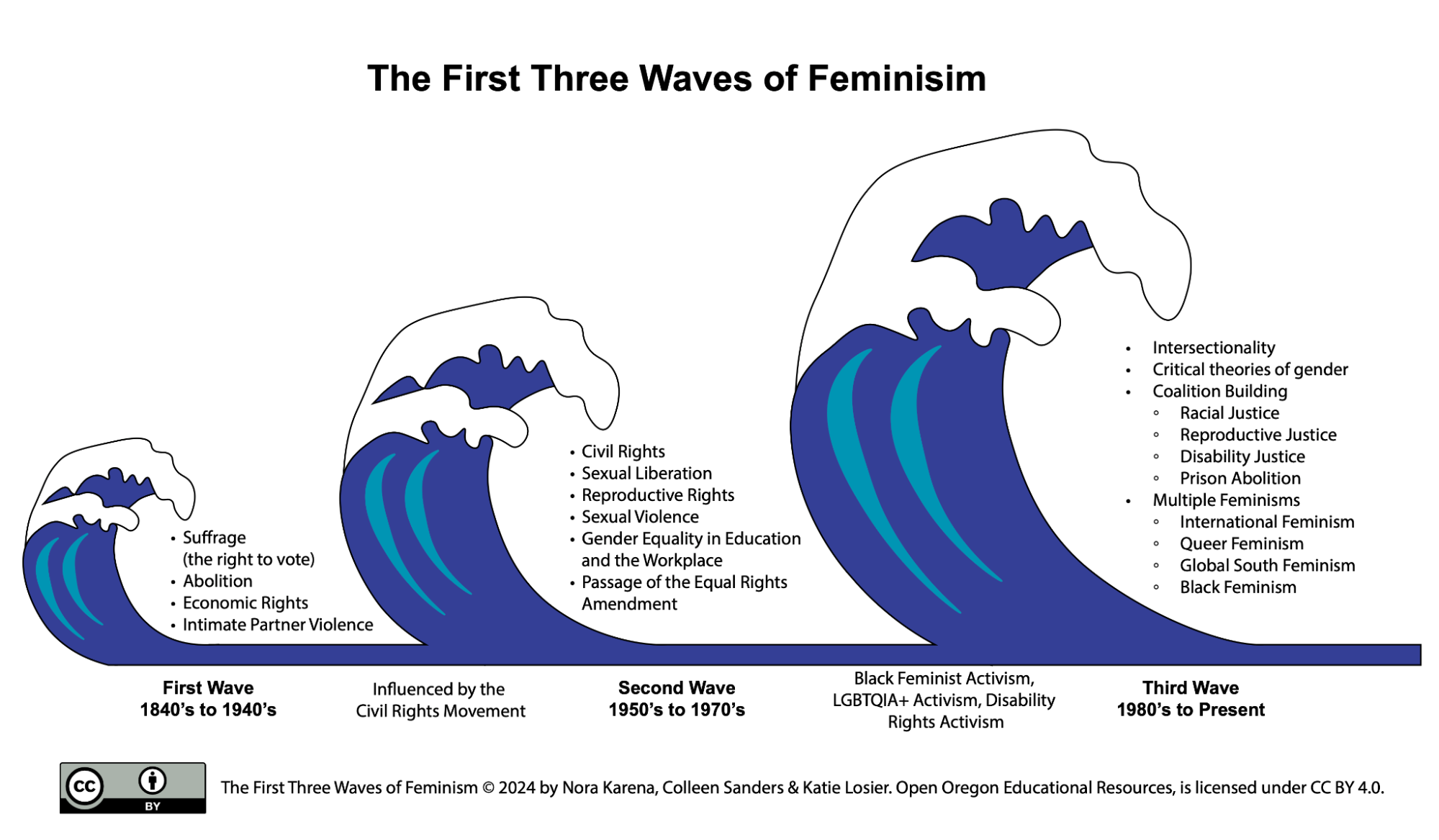

Scholars think of the feminist movement in three historical “waves,” each expanding available knowledge when people previously excluded as knowledge producers demanded full inclusion. The first wave, in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was marked by movement activism to end slavery and secure voting rights for women. The second wave, in the mid-20th century, was also tied to the struggle for Black Freedom, and as in the first wave, it was sometimes derailed by false choices between the liberation of women and civil rights for all people. The third wave, from the 1990s to the present day, takes issue with exclusionary feminisms and builds a more intersectional body of theory and more coalitional activism that centers the standpoints of people who are disabled, people who identify as LGBTQIA+, and People of the Global Majority.

First Wave Feminism

The “first wave” of the feminist movement began in the mid-19th century and lasted until the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920, which gave women the right to vote (figure 4.7). White middle-class feminists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony primarily focused on women’s suffrage (the right to vote), striking down coverture laws (that give husband ownership of his wife’s property), and gaining access to education and employment. These goals are famously enshrined in the Seneca Falls Declaration of Sentiments from the first women’s rights convention in the United States in 1848.

White middle-class abolitionists often made analogies between slavery and marriage. As abolitionist Antoinette Brown wrote in 1853, “The wife owes service and labor to her husband as much and as absolutely as the slave does to his master” (Brown, cited in Cott, 2000 p. 64). This analogy between marriage and slavery confused the unique experience of the racialized oppression of slavery that Black women faced with a very different type of oppression faced by white women who were legally considered to be subject to their husband’s authority. While white women abolitionists and feminists of the time made important contributions to anti-slavery campaigns, they often failed to understand the uniqueness and severity of slave women’s lives and the complex system of chattel slavery (Davis, 1983).

Despite their marginalization, Black women were passionate and powerful leaders. Ida B. Wells (figure 4.8) (she/her) (1683–1931), who participated in the movement for women’s suffrage, was a founding member of the National Association of the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). She was also a journalist and the author of numerous pamphlets and articles exposing the violent lynching of thousands of African Americans. Wells argued that lynching was a systematic attempt to maintain racial inequality (Wells 1979). Additionally, thousands of Black women were members of the National Association of Colored Women’s Clubs, which was pro-suffrage, but did not receive recognition from the predominantly middle-class, white National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA).

Second-Wave Feminism

The emergence of feminist sociology can be traced to this period, and like the larger second-wave feminist movement, was influenced and facilitated by the activist tools provided by the civil rights movement. The actions described in the opening of this chapter are an example of this influence. When the women of the American Sociological Society held a separate caucus, they produced a statement with demands for equality and presented it to the next business meeting, where they applied lessons learned from the movement for civil rights. Feminist sociologists then turned their attention to researching, documenting, and theorizing about the specific lived experiences of women and girls in all the social settings where they were ignored by masculine-dominated social science.

Social movements change according to movement gains or losses, depending on their political and social contexts. Following women’s suffrage in 1920, feminist activists channeled their energy into institutionalized legal and political channels to effect changes in labor laws and to attack discrimination against women in the workplace.

Despite the conservative political climate of the 1940s and 1950s, civil rights organizers began to challenge both the de jure segregation of Jim Crow laws and the de facto segregation experienced by African Americans on a daily basis. The landmark Brown v. Board of Education ruling of 1954, which made “separate but equal” educational facilities illegal, provided an essential legal basis for activism against the institutionalized racism of Jim Crow laws.

The Black Freedom Movement, of which the Civil Rights Movement was a part, fundamentally changed U.S. society and inspired the second-wave feminist movement and the radical political movements of the New Left (e.g., gay liberationism, black nationalism, socialist and anarchist activism, the environmentalist movement) in the late 1960s. The Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), initiated by Ella Baker (figure 4.9), was an important catalyst.

Not only did many women involved in the civil rights movement become activists in the second-wave feminist movement, but they also used tactics from the civil rights movement, including marches, caucusing, and non-violent direct action. Feminists in the civil rights movement challenged gender norms that excluded women from politics and restricted them to the domestic sphere (Du Bois & Dumenil 2005).

LEARN MORE: Students in The Civil Rights Movement

To learn more about the work of student organizers in the civil rights era, watch: Student Civil Rights Activism: Crash Course Black American History #37 [Streaming Video].

Although the second-wave feminist movement challenged gendered inequalities and brought women’s issues to the forefront of national politics in the late 1960s and 1970s, the movement also reproduced race and sex inequalities. Becky Thompson argues that by the mid and late 1960s, Latina women, African American women, and Asian American women were developing multiracial feminist organizations. These racially specific groups would become important and challenge racism and homophobia within feminist movements (Thompson 2002).

In the late 20th century, radical women of the global majority, including some who also identified as LGBTQIA+, wrote powerfully about “the complex confluence of identities-race, class, gender, and sexuality-systemic to women of color oppression and liberation” (Moraga et al., 1981). These scholars, poets, and activists had a profound impact on gender theories. Their work, including This Bridge Called My Back: Writings by Radical Women of Color (figure 4.10), drew from personal experiences of oppression and marginalization in feminist spaces, where they were marginalized as women of color, and in masculine-dominated racial justice spaces, where they were marginalized as women. Those who also identified as LQBTQIA+ and experienced oppression in both feminist and racial justice spaces asserted that their specific knowledge and experience as women of the global majority were critical to the struggle against oppression.

In Black Feminist Thought, Patricia Hill Collins describes the specific impacts of racism and sexism on black women. She describes her struggle “to replace the external definitions of my life forwarded by dominant groups with my own self-defined viewpoint” (Hill Collins, 2022). Hill Collins argued that liberatory theory must be centered on the lived experience of those who are marginalized by dominant systems of power. In other words, the necessary knowledge to dismantle systems of power sits with those who are marginalized by those systems.

Third Wave Feminism

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JCYCGQmjz70

Third-wave feminism is influenced by earlier waves but has expanded to include a multitude of standpoint-specific feminisms developed by Black women, transnational women, women of the Global South, disabled women, and people who are LGBTQIA+. A defining characteristic of the third wave is coalitional politics. Coalitional politics refers to political association with those who have differing identities around shared experiences of oppression (Taylor 2017). This is in contrast to identity politics, which refers to organizing politically around the experiences and needs of people who share a particular identity. Identity politics is a coin termed in the 1980s and was commonly derided as “the oppression Olympics.” Coalitional politics avoids this by addressing shared interest from identity-specific perspectives. To see coalitional politics in action, watch the video in figure 4.11 about Freedom Inc. in Madison, Wisconsin, which describes itself as “a Black and Southeast Asian non-profit organization that works with low- to no-income communities of color” (Freedom Inc. 2017).

Recall from Chapter Three that, during the early HIV/AIDS Crisis, another example of coalitional politics emerged in solidarity with gay men, who were the first group to be disproportionately impacted by the deadly virus. This movement inspired a significant social shift in social norms about sex and gender.

However, since this movement did not specifically address racial discrimination or the economic conditions of poor people, this social progress unevenly benefited middle-class white people at the expense and continued marginalization of people of the global majority, disabled, trans, single or non-monogamous, or low income. In response, more radical subsets of activists began to explicitly reclaim the derogatory term “queer” to describe their activism and set themselves apart from more mainstream organizing.

People outside the U.S. have also broadened the feminist frameworks for analysis and action. In a world characterized by global capitalism, transnational immigration, and a history of settler-colonialism that still has effects today, transnational feminism is a body of theory and activism that highlights the connections between sexism, racism, classism, and imperialism. Transnational feminist theorist Chandra Talpade Mohanty (she/her) (figure 4.12) critiques feminist activism and theory that prioritizes a white, North American standpoint and ignores the needs and political situations of women in the Global South (Mohanty et. al. 1991). Transnational feminists argue that Western feminist projects to “save” women in another region do not liberate these women, since this approach constructs the women as passive victims devoid of agency to save themselves. These “saving” projects are especially problematic when they are accompanied by Western military intervention.

Third-wave feminism is a vibrant mix of differing activist and theoretical traditions that grapples with multiple points of view and refuses to be pinned down as representing just one group of people or one perspective. Similar to the way queer activists and theorists have insisted that “queer” is and should be open-ended and never set to mean one thing, third-wave feminism’s complexity, nuance, and adaptability become assets in a world marked by rapidly shifting political situations. The third wave’s insistence on coalitional politics as an alternative to identity-based politics is a crucial project in a world that is marked by multiple overlapping inequalities. Now that you’ve surveyed feminist movements and feminist theory from the first wave to the third wave (figure 4.13) let’s take a deeper dive into some contemporary gender theories.

LEARN MORE:Gender Conflict Theory

Watch Harriet Martineau & Gender Conflict Theory: Crash Course Sociology #8 [Streaming Video] for a quick review of the history of feminism and feminist theory.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Feminist Activism and Theory

Open Content, Original

Figure 4.13. “Three Waves of Feminism” by Nora Karena and Katie Losier, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Feminist Activism and Theory Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Feminist Activism and Theory” is adapted from “Historical And Contemporary Feminist Social Movements” by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, and Sonny Nordmarken, Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena include the introductory paragraphs about standpoint theory and minor edits and remixes for length, style, and context.

Figure 4.7. “Votes for Women’ sellers, 1908.” courtesy of The Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science is in the Public Domain.

Figure. 4.8. “Mary Garrity – Ida B. Wells-Barnett – Google Art Project – restoration crop” by Adam Cuerden is in the Public Domain.

Figure 4.12. “Chandra Talpade Mohanty (2011)” by Dr. Chandra Mohanty is in the Public Domain, CC0 1.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Coalitional politics” definition from Taylor (2017) is included under fair use.

“Standpoint theory” definition by Sandra Harding (1992) is included under fair use.

Figure 4.6. Photo © Sandra Harding, UCLA is included with permission.

Figure 4.9. “Ella Baker 1964” by The Ella Baker Center for Human Rights is included under fair use.

Figure 4.10. Image from Persephone Press is included under fair use.

Figure 4.11.”Our Story: Building Black and Hmoog Movement” by Freedom, Inc. is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

“Harriet Martineau & Gender Conflict Theory: Crash Course Sociology #8” by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

“Student Civil Rights Activism: Crash Course Black American History #37” by CrashCourse is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual, Plus a continuously expanding spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations.

argues that knowledge is socially situated and that the dominant standpoint of social and natural sciences has been based on “rampant sexism and androcentrism (centering men)” (Harding, 1992).

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Chandler & Munday, 2011).

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

purposeful, organized groups that strive to work toward a common social goal.

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

is an interdisciplinary approach to issues of equality and equity based on gender, gender expression, gender identity, sex, and sexuality as understood through social theories and political activism (Eastern Kentucky University, n.d.)

refers to political association with those who have differing identities, around shared experiences of oppression (Taylor, 2017).

which refers to organizing politically around the experiences and needs of people who share a particular identity.

a complex competitive economic system of power in which limited resources are subject to private ownership and the accumulation of surplus is rewarded.

is a body of theory and activism that highlights the connections between sexism, racism, classism, and imperialism.