4.5 Theorizing the Gender Wage Gap

You have seen throughout the chapters of this book that social inequality is a prominent theme in sociology, and gender inequality is a specific concern of the sociology of gender. Let’s complete our discussion of theory by using the tools of sociology to examine a persistent indicator of gender inequality, the gender wage gap.

In 2022, the gender wage gap—the difference between the median wages of men and women working full-time year-round—was 16%, which means women working full-time year-round received 84 cents for every dollar paid to men. Compared to white, non-Hispanic men, the wage gaps were 20% for white, non-Hispanic women; 31% for Black women; and 43% for Hispanic women (U.S. Department n.d.). As you work through this section pay attention to how sociologists use both micro and macro-level analysis to describe the individual and social factors that produce the gender wage gap.

Early Theoretical Perspectives

Classic conflict theory does not adequately account for gendered wage inequities. Conflict theorists might analyze how corporations in advanced capitalist societies, like the U.S., exploit workers’ labor to maximize profits for owners and shareholders. By paying some workers less than others (and all workers less than the actual value of their labor), those at the top increase their wealth, while lower-wage workers are led to believe they too can join the upper classes if they work hard enough. Of course, the system depends on there always being a larger number of low-wage workers to generate the necessary profits. They might also analyze the unequal ratio of women to higher-paying positions. Gender conflict theory, inspired by feminism theory does, however, analyze how economic gender inequality supports patriarchal power structures in the workplace and the marketplace.

Structural functionalists might look at how values and norms shape societal notions of success in the workforce and how these established values and norms reinforce the division of labor and gender inequality. For functionalists, when gender roles are established, social solidarity increases. When large numbers of women began to enter the workforce starting in World War II due to labor needs, they were paid less. Employers argued that this was a necessary cost-saving measure during wartime. When women collectively began to demand equal pay for equal work, emerging values and norms were reinforced by new labor laws that prohibited gender discrimination in the workplace. These laws do not address the values and norms that drive persistent occupational segregation, which concentrates women in lower-paying categories of work.

Interactionists would likely examine how meaning, in the form of race and gender stereotypes and controlling images (Hill Collins 2022), is produced and negotiated in social interactions and then translated into wage inequality. A woman who displays certain behaviors that are generally understood as appropriate for leadership (i.e., strong, opinionated, concise) might be perceived as bossy or difficult to work with. In contrast, a man with the same behaviors would be perceived as having leadership potential. This type of meaning-making, which is heavily gendered through generational cycles of socialization, contributes to the wage gap at the micro-sociological level.

Feminist Theoretical Perspectives

A feminist theoretical perspective of the gender wage gap helps us see how systems of power like patriarchy create the social conditions that lead to gender-based income inequality. According to the Department of Labor, occupational segregation is a long-standing driver of the persistent pay inequities experienced by women in the U.S. (U.S. Department of Labor n.d.).

Occupational segregation is a form of social stratification in the labor market in which one group is more likely to do certain types of work than other groups. Gender-based occupational segregation describes situations in which women are more likely to do certain jobs and men do others.

The jobs women are more likely to hold have been dubbed pink-collar jobs. Men have traditionally held well-paying white-collar jobs and manual labor or blue-collar jobs with a full range of income levels depending on skill and experience, though many women hold these jobs now, as well. Pink-collar jobs are low-wage jobs disproportionately held by women. Pink-collar jobs include childcare, customer service, personal services, and direct social services. A common theme in pink-collar jobs is that, in addition to technical skills and subject matter expertise, they also require emotional labor.

Sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild (figure 4.18) (she/her) introduced the term emotional labor to describe work that requires managing personal emotions and the emotions of other people (1983). For example, food servers risk losing their jobs if they respond to rude and harassing customers with otherwise appropriate anger. It is a routine part of a server’s job to both control their emotional reactions and to soothe the emotions of unhappy customers. Any service-based work that involves interacting with the public also involves emotional labor. Even higher-paying, highly skilled pink-collar occupations, like administrative assistants, teachers, and nurses, involve emotional labor.

Nail technicians are an example of a pink-collar job that requires a high degree of technical skill and intense emotional labor. While clients may see the technician as their trusted confidant, with whom they share intimate secrets, this relationship is actually an economic one in which the worker is paid not only for the service they perform but also for their personality and listening skills.

Miliann Kang (she/her) has conducted research with immigrant women who work in beauty service work, particularly nail salons. Kang refers to this labor involving both emotional and physical labor as body labor. To engage in both emotional and physical labor at work is exhausting. In addition, workers in nail and hair salons work with harsh chemicals that are ultimately toxic to their health and make them more susceptible to cancer than the general population (Kang 2010).

LEARN MORE: Body Labor

To learn more about the routine exploitation of workers who perform emotional labor, check out Milian Kang’s presentation about her work: Miliann Kang – UCSB Intimate Labors Presentation [Streaming Video].

Unpaid care work is another category of labor that contributes to the gender wage gap. A study by the National Alliance for Caregiving and the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) found that around 43.5 million people provided unpaid care to an adult or child between 2014 and 2015 (AARP 2015). More than 75% of caregivers are women (Institute on Aging n.d.). Economist Nancy Folbre (she/her) (2010) has argued that care work is undervalued both because women are more likely to do it and because it is stereotypically understood as women’s work.

Gender-based occupational segregation alone does not account for the fact that for every dollar that White men make, Black women make only sixty-four cents. Nor does racism alone account for Black women comprising 25% of the poor people in the U.S., compared to 18% of Black men. To fully account for the economic marginalization of Black women and other women of the global majority, we must take multiple systems of power into account. Black women and immigrant women disproportionately hold lower-paying service jobs in healthcare and other service industries (U.S. Department n.d). Data that includes both race and gender reveals that the wage gap for Black women and immigrant women is driven by both race- and gender-based occupational segregation. In Chapter Five, you will learn how intersectional analysis can reveal complex hierarchies of social stratification.

Contemporary Theoretical Perspectives and the Gender Pay Gap

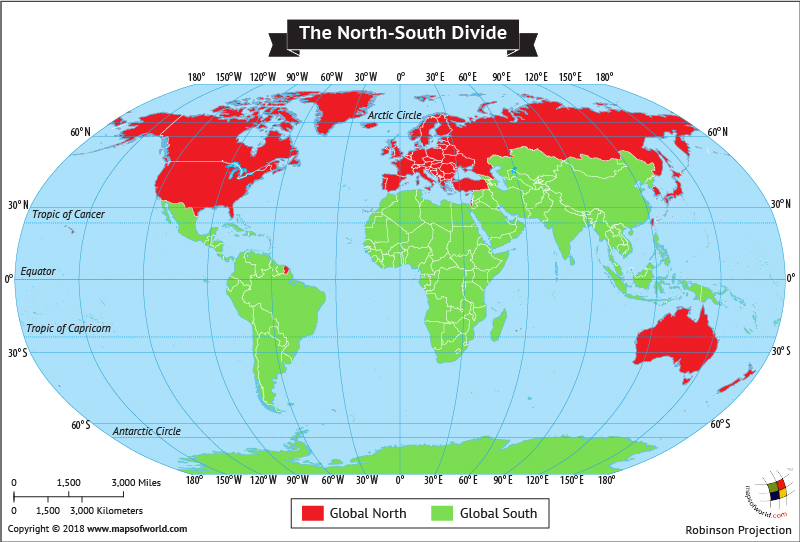

Contemporary theories of gender are concerned with the impact of the global economy in terms of the economic situations of the nations in which they live and also by gender and race. The map in figure 4.19 shows the countries of the global north in red and the countries of the global south in green. Notice that many of the countries of the global south were once colonized by countries in the global south. Contemporary trade relationships between the Global North and the Global South frequently reproduce a political situation similar to colonization in many nations of the Global South. Postcolonial scholars characterize the current global economic system as a form of neocolonialism, or modern-day colonization characterized by the exploitation of a nation’s resources and people. Colonialism and neocolonialism are concepts that draw attention to the economic inequalities between historical colonizers and the historically colonized.

Postcolonial theory originated with scholars from former European colonies in the global south. Postcolonial theory explores how colonization disrupts social arrangements, including gender relations of the people who lived in colonized places. Gender-based differences in work and pay for women of the global south are an example of the ongoing results of colonialism.

Postcolonial scholarship examines and critiques colonial discourses, depictions of colonized Others, and European scholars’ biased representations of those they colonized, which they figure as knowledge. Postcolonial theory reveals how European ideas about people in countries that have been European colonies are shaped by the same derogatory and dehumanizing colonial perspectives of colonized populations that colonizers made up to justify their domination and subjugation of other people and their resources (Said 1995; Spivak 1988).

Postcolonial theoretical approaches, emerging chiefly from the global south, illuminate how the process of colonization disrupted the social arrangements, communities, gender relations, and cultures of the people who lived in colonized places. Among other cultural harms, colonization imposed European racialized conceptualizations of binary gender norms (Quijano 2007; Lugones 2007). Here again, we see the importance of standpoint. In this case, the standpoints of scholars from former colonies challenged the paternalistic social science of the colonizers.

Not only do gendered, racialized, and sexualized differences exist in the U.S. domestic labor market, leading to differences in work and pay, but these differences also impact the globalized labor market. Women of the Global South are disproportionately impacted by global economic policies. Not only are women in Asian and Latin American countries much more likely to work in low-wage factory jobs than men, but women are also much more mobile in terms of immigration (Pessar & Mahler 2003). Migrant women generally work in the pink-color service sector. Those who are undocumented are especially vulnerable to exploitation in illegal and unregulated markets in nations of the Global North rather than regulated markets of the formal economy.

Unjust trade relationships between countries have profound effects on the quality of life of people all over the world. Women bear the brunt of changes in the global marketplace as factory workers in some countries and pink-collar service workers in others.

Real But Not True: The Gender Wage Gap

Let’s consider how what you are learning about the Gender Wage Gap demonstrates that binary gender is socially constructed (not true) and has real-life consequences (real).

The tools of sociology include:

- Sociological Imagination

- Research-based Evidence

- Social Theory

Gender conflict theory analyzes how economic gender inequality supports patriarchal power structures in the workplace and the marketplace.

A feminist theoretical perspective of the gender wage gap helps us see how systems of power like patriarchy create the social conditions that lead to gender-based income inequality.

Postcolonial theoretical approaches, emerging chiefly from the global south, illuminate how the process of colonization disrupted the social arrangements, communities, gender relations, and cultures of the people who lived in colonized places. Gender, racialized, leading to gender-based differences in work and pay for women of the Global South.

We can recognize that socially constructed meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to women in the labor force are not universally true when we can demonstrate that they:

- Change over time

- Are not the same in all societies

- Are imposed, enforced, reproduced, negotiated, or challenged through social interactions.

Occupational segregation is a form of social stratification in the labor market in which one group is more likely to do certain types of work than other groups.

Gender-based occupational segregation describes situations in which women are more likely to do certain jobs and men do others.

The jobs women are more likely to hold have been dubbed pink-collar jobs. Men have traditionally held well-paying white-collar jobs and manual labor or blue-collar jobs with a full range of income levels depending on skill and experience, though many women hold these jobs now, as well. Pink-collar jobs are low-wage jobs disproportionately held by women.

Data that includes both race and gender reveals that the wage gap for Black women and immigrant women is driven by both race- and gender-based occupational segregation.

The real social consequences of the gender wage gap include

- In 2022, the gender wage gap—the difference between the median wages of men and women working full-time year-round—was 16%, which means women working full-time year-round received 84 cents for every dollar paid to men.

- Compared to white, non-Hispanic men, the wage gaps were 20% for white, non-Hispanic women; 31% for Black women; and 43% for Hispanic women.

- Women in Asian and Latin American countries are much more likely to work in low-wage factory jobs.

- Migrant women are especially vulnerable to exploitation in illegal and unregulated markets in nations of the Global North, rather than regulated markets of the formal economy.

As you continue to work through this book, be on the lookout for other examples of socially constructed meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences and for the ways that tools of sociology can be used to reveal them as social constructions that are not universally true, but have real consequences.

LEARN MORE: Transnational Mothers

When women migrate, they may be forced to sacrifice care of and contact with their own children in order to earn money caring for wealthier people’s children as domestic workers; this situation is known as transnational motherhood (Parreñas, 2001). To learn more about the experience of transnational mothers, watch Dos Madres: With courage and patience, two migrant mothers share their stories [Streaming Video].

Let’s Review

Looking Through the Lens: Queer Theory

In Chapter Three, you used the Gender Unicorn tool to describe your unique gender and sexuality. To demonstrate how flexible our understanding of gender and sexuality can be, this reflexive exercise invites you to use a queer theory lens in order to think about sexual orientation in new ways.

Step 1. Consider this:

Queer theory is an interdisciplinary approach to the study of sexuality studies that challenges the social construct of the gender binary and questions how we have been taught to think about sexual orientation. According to Annamarie Jagose (she/her) (1996), queer theory focuses on mismatches between sex assigned at birth, gender identity, and sexual orientation, not just division into male/female or homosexual/heterosexual. Queer theory gives us a generous framework to think about the multiplicity of ways people understand and experience sex, gender, and sexuality.

By calling their discipline “queer,” scholars reject the effects of labeling; instead, they embraced the word “queer” and reclaimed it for their own purposes. The perspective highlights the need for a more flexible and fluid conceptualization of sexuality—one that allows for change, negotiation, and freedom. This approach can also be applied to other oppressive binaries in our culture, especially those surrounding gender and race (Black versus White, man versus woman).

Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick argued against the dominant definition of sexuality reduced to a single factor: the sex of someone’s desired partner. Sedgwick identified dozens of other ways in which people’s sexualities can be defined, including:

- Differences in the meaning of specific genital acts (identical genital acts can mean very different things to different people).

- Sexuality makes up a large share of the self-perceived identity of some people and a small share of others.

- Some people spend a lot of time thinking about sex, others little.

- Some people like to have a lot of sex, others little or none.

- Some people like spontaneous sexual scenes, others like highly scripted ones, and still others like spontaneous-sounding ones that are nonetheless totally predictable.

- Some people experience their sexuality in terms of gender meanings and gender differences. Others do not (Sedgwick, 1990).

Step 2: For each continuum of sexuality, find the number between one and ten that best describes your relationship with that aspect of sexuality. There are no wrong answers, and you don’t have to share this with anyone else.

- How do you feel about oral sex?

1 = doesn’t really count as sex, 10 = only with someone I am in a committed intimate relationship with - How important is sexuality to your identity?

1 = not at all important, 10 = the most important aspect of my identity - How much do you think about sex?

1 = I never think about sex, 10 = I always think about sex - How often do you want to have sex?

1 = I never want to have sex, 10 = I want to have sex multiple times a day - How spontaneous do you want sex to be?

1= I only want to have spontaneous sex. 10 = I only want sex to be planned and scripted - Does having sex feel like an expression of your gender?

1 = how I have sex has nothing to do with my gender expression, 10 = I feel most affirmed in my gender expression when I have sex

Step Three: Use your responses to answer the following prompts and think about how you might describe your sexuality in ways that don’t include the gender of your sexual partner.

- Which of these aspects of sexual orientation is most important to you? Least important?

- How did it feel to think about your sexual orientation in this way?

- What are you learning from this lesson about the social construction of gender and sexuality?

Licenses and Attributions for Theorizing the Gender Pay Gap

Open Content, Original

“Real But Not True: The Gender Wage Gap” By Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Real But Not True Puzzle Images” by Nora Karena and Katie Losier are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Theorizing the Gender Wage Gap Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Theorizing the Gender Pay Gap” is adapted from “Theoretical Perspectives on Gender” by Sarah Hoiland and Lumen Learning, Introduction to Sociology, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Heidi Esbensen include adding introductory paragraphs and editing them for relevance.

“Feminist Theoretical Perspectives and the Gender Pay Gap” is adapted from “Gender and Work in the U.S.” by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken in Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Heidi Esbensen and Nora Karena include edits for length, style, and context.

“Contemporary Theoretical Perspectives and the Gender Pay Gap” is adapted from “Racialized, Gendered, and Sexualized Labor in the Global Economy” by Miliann Kang, Donovan Lessard, Laura Heston, Sonny Nordmarken, Introduction to Women, Gender, Sexuality Studies, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena include edits for length, style, and context.

“Looking Through the Lens: Queer Theory” is adapted from “Sexuality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications include edits by Dana L. Pertermann and questions by Heidi Esbensen.

Figure 4.18. “Arlie Russel Hochschild” by Paul572 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Emotional labor” definition by Hochschild (1983) included under fair use.

Figure 4.19. “Global North v Global South Divide” by mapsofworld.com is included under fair use.

the unequal distribution of power and resources based on gender.

applies the tools of sociology to explore how gender, including sexuality, gender expression, and identity, is socially constructed, imposed, enforced, reproduced, and negotiated.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

is a macro-level theory that proposes conflict is a basic fact of social life, which argues that the institutions of society benefit the powerful.

is an interdisciplinary approach to issues of equality and equity based on gender, gender expression, gender identity, sex, and sexuality as understood through social theories and political activism (Eastern Kentucky University, n.d.)

is a form of social stratification in the labor market in which one group is more likely to do certain types of work than other groups. Gender-based occupational segregation describes situations in which women are more likely to do certain jobs and men do others.

the process of learning culture through social interactions.

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

literally the rule of fathers. A patriarchal society is one where characteristics associated with masculinity signify more power and status than those associated with femininity.

a set of processes in which people are sorted, or layered, into ranked social categories based on factors like wealth, income, education, family background, and status.

to describe work that requires managing personal emotions and the emotions of other people (Hochschild, 1983)

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Chandler & Munday, 2011).

originated with scholars from former European colonies in the global south whose global south. Postcolonial theory explores how colonization disrupts social arrangements, including gender relations of the people who lived in colonized places. Gender-based differences in work and pay for women of the global south are an example of the ongoing results of colonialism.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior, experience, and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. (Mills 1959)

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

a framework for understanding gender and sexual practices outside of heterosexuality.

emotional, romantic, or sexual attraction to other people; often used to signify the relationship between a person’s gender identity and the gender identities to which a person is most attracted (Learning for Justice 2018).

shared meaning that is created, accepted, and reproduced by social interactions between people within a society.

a limited system of gender classification in which gender can only be masculine or feminine. This way of thinking about gender is specific to certain cultures and is not culturally, historically, or biologically universal.

the assignment and classification of people as male, female, intersex, or another sex based on a combination of anatomy, hormones, and chromosomes.

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

the way our gender identity is expressed outwardly through clothing, personal grooming, self-adornment, physical posture and gestures, and other elements of self-presentation.