5.4 Gender in Global Systems of Power

In 2023, ten pieces of legislation were introduced in Oregon that, if passed, would have negatively impacted LGBTQIA+ people, including making menstrual products harder to access for transgender and nonbinary students, requiring parental consent before using materials that included representation of LGBTQIA+ people (an example of so-called “Don’t say gay laws”), restrict access to gender-affirming care for transgender youth, and discriminate against transgender athletes (Trans Legislation Tracker 2024). None of these bills passed in Oregon, but of the more than 500 anti-LGBTQIA+ bills introduced in state legislatures in 2023, 85 of them passed in 23 states (Choi 2024). As of January 2024, over 400 similar bills have been introduced in 37 states (Trans Legislation Tracker 2024).

This recent rise in anti-LGBTIA+ legislation in the U.S. is related to a similar trend worldwide. Dr. Sylvia Tamale (she/her) is a multidisciplinary scholar who was the first woman to serve as the Dean of Law at Makerere University Law School and the founder of the Law, Gender and Sexuality Research Project (Tamale n.d.) (figure 5.12). She has been an outspoken critic of the increase in homophobic rhetoric and policies in Uganda and other African Nations and claims that a “power elite rewritten the history of African sexualities, obliterating same-sex relations to bolster their control over the political and social context.” She also names American Evangelicalism as a driver of these homophobic narratives and the policies they inspired (Tamale n.d.).

Tamale challenges an emerging narrative that credits increasing global tolerance for queer sexualities with colonialism and Western cultural dominance. Her work names this distortion of African history by demonstrating a robust precolonial “handprint of homosexuality” in African history, which includes examples of tolerance for a variety of sexual and domestic relationships, including marriage between same-sex couples.

This section will consider two complex intersecting unequal systems of power, Capitalist Heteropatriarchy and White Supremacist Settler Colonialism. We will consider how these systems of power have impacted people in formerly colonized countries in terms of traditional genders, gender expressions, and sexualities.

Learn More: Africa

To learn more about the rich variation of genders, gender expression, and sexualities in precolonial African cultures, check out The “Deviant” African Genders That Colonialism Condemned [Website] by Mohammed Elnaiem [Website] (he/him).

To learn more about feminism on the African Continent, watch Know Your African Feminists [Streaming Video].

Capitalist Heteropatriarchy

The U.S. economic system functions by privileging a minority of people to profit from privatizing resources that are extracted, commodified, and sold at a profit while the majority of workers sell their labor. Capitalism is a complex, competitive economic system of power in which limited resources are subject to private ownership, and the accumulation of surplus is rewarded. In other words, capitalism is the use of land, labor, and capital wealth, in the form of money or other assets, to create profit (Zimbalist et al. 1988). Winning in a capitalist system requires someone to lose. Capitalism produces a class-based unequal system of power in which some classes of people are empowered to win at the expense of others who are marginalized.

Recall from Chapter One that patriarchy is a gender-based system of power. A patriarchal society is one where characteristics associated with masculinity signify more power and status than those associated with femininity. In patriarchal societies, gender differences produce gender inequality, with the father or eldest male being head of the family and descent (or who you’re related to) traced through the male line. Within patriarchal systems, women are collectively excluded from full participation in political and economic life. Those attributes seen as feminine are undervalued. Patriarchal relations structure both the private and public spheres, with men making the important decisions or “holding the reins of power” in both domestic and public life (Nash 2009).

Patriarchy also closely links gender and sexuality so that genders are considered to be opposite from each other, and a person’s gender identity must correlate with sexual attraction to a gender that is opposite. This leaves little room for genders or sexualities that don’t fit firmly into a binary category. In patriarchal societies, same-gender attraction is marginalized or outright forbidden because sex is socially constructed as a “natural” expression of masculine dominance and feminine submission.

Patriarchal societies tend to marginalize people whose gender presentation differs from their assigned gender and to exclude transgender and nonbinary from full participation in society. Heteropatriarchy (a merging of the words heterosexual and patriarchy) is a system of power in which cisgender and heterosexual men have authority over everyone else. This term emphasizes that discrimination against women and LGBTQIA+ people is derived from the same sexist social principle (Valdes 1996).

The gender wage gap, introduced in Chapter One, demonstrates how capitalism, a class-based system of power, and heteropatriarchy, a system of power based on gender and sexuality, work together on a global scale to produce intersectional wealth inequality based on class, gender, and sexuality. Feminist scholarship links heteropatriarchy and capitalism, demonstrating how heteropatriarchal relations operate across and between many systems in ways that reinforce a complex system in which cisgender heterosexual (cishet) men win at the expense of everyone else (Acker 1989; Mohanty 2013).

Some capitalists argue that capitalist economies are rational, unbiased, and self-regulating. Yet the current global capitalist system has been and remains empowered by white supremacy and settler colonialism (Nguyen 2020). Under this system, people themselves become capital and are treated not as fellow humans but as assets for profit.

White Supremacy and Settler Colonialism

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWVWy7aGtGw

As feminist activism has challenged masculine dominance, new opportunities in politics, economics, and popular culture have emerged for women and people who identify as LGBTQIA+. While many people of all genders welcome this social change, some people argue that feminism is unfair to men. This is similar to the argument that white people are treated unfairly when antiracist progress creates more opportunities for people of the global majority. Both of these types of grievance over lost dominance have become a prominent theme in many extremist ideologies (Díaz & Valji 2019). Here in the U.S., the link between aggrieved masculinity and the politics of White Nationalism is illustrated in actions like protesting drag queen story hour (figure 5.13).

Drag Queen Story Hour events are intended to be celebrations of literacy and inclusion. Parents who take their children to these events value the opportunity to teach their children about gender expression and to hear an uplifting story. These otherwise joyful events have become sites of violence and intimidation, where children, their families, and the drag queens are harassed by neo-nazis and other anti-LGBTQIA+ protesters.

The advocacy organization GLAAD (formerly the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation) documented 161 incidents of demonstrations and threats targeting drag events between early 2022 and spring 2023 (GLAAD 2023). Moral panic in response to changing cultural norms around gender and sexuality has emboldened violence and empowered legislation to ban or severely restrict drag entertainment.

Neo-nazi groups, Ku Klux Klan, and other groups, including right-wing para-military organizations like The Patriot Front and the Proud Boys, represent the White Nationalist political movement in the U.S. White Nationalism is an international political movement built on White Supremacy, Christian political identity, capitalism, heteropatriarchy, and authoritarianism. The Third Reich in Germany during Hitler’s reign (1933–1944), Apartheid South Africa (1948–1991), and the U.S. during the years when slavery was legal (1776–1863), and during the Jim Crow era (1883–1965), when racial segregation and discrimination were legal, are examples of white nationalist nation-states.

White supremacy is a complex system of racist power that is based on discredited racist enlightenment-era social science (Chapter One) and constructed through policies and practices that privileged White people over people of other races, based on the racist ideas that that there are meaningful differences between people in different racial categories, that White people are physically and culturally superior, and that they are therefore entitled to dominate other people in other racial categories. White supremacy, which, like other unequal systems of power, is based on domination. In the same way that sexism is based on the domination of women and People who are LGBTQIA+, racism is based on the domination of people who are not White. It is ideologically aligned with heteropatriarchy, capitalism, and settler colonialism.

Restricting our definition of white supremacy to its most extreme aspects puts us at risk of not seeing the everyday violence of white supremacy (figure 5.14). Many people associate white supremacy with extreme violence carried out by members of the Ku Klux Klan and other White nationalist organizations. However, White Supremacy is more than the violent political movements it inspires. It is present wherever a racialized hierarchy privileges people who are White over People of the Global Majority. Like all systems of power, it operates across all four domains of power (figure 5.15). While the interpersonal aspects of White Supremacy are most visible in the form of hate groups and bigots, it can be most powerful in structural, cultural, and disciplinary domains.

| DOMAINS OF POWER | SOURCES OF POWER |

|---|---|

| Structural – The power to rule | Discriminatory hiring practices, Discriminatory lending policies, English-only initiatives… |

| Disciplinary – the power to punish and reward | Mass incarceration, racial profiling, anti-immigration policies… |

| Hegemonic (Cultural) – the power to influence | Racist mascots, Eurocentric curriculum, Cultural appropriation… |

| Interpersonal – the power of self-determination | Racist jokes and slurs, not believing the experience of people of the global majority, Hate Crimes… |

Because they are complex, White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, Heteropatriarchy, and Capitalism also include multiple systems of power that intersect with racism. Returning to the Wheel of Power and Privilege (figure 5.6), we can understand that white supremacy is constructed by multiple intersecting systems of power, including sexism, nativism, xenophobia, and heterosexism. For many scholars of White Supremacy, the long-term goal of challenging White Supremacy is directly tied up with the project of dismantling the capitalist market system (Lugones 2016). Can you imagine what a system of power might look like if it benefits everyone without resorting to exploitation, domination, or conformity to false binaries?

Like capitalism and white supremacy, settler colonization is also achieved in social, disciplinary, cultural, and interpersonal domains. Settler colonialism is an unequal system of power that relies on white supremacy to justify removing established indigenous residents of colonized territory so that the land can be occupied by settlers and its resources used for the benefit of the occupying power.

The European colonization of the Americas was a violent process that resulted in the death of 90% of the pre-conquest Indigenous population, the transformation of the land and natural resources previously held by Indigenous societies into private property held by European settlers, and securing territorial control for colonizing empires. As settlers created their European settler colonization, it also compelled surviving Indigenous people in the Americas to assimilate into the dominant White Supremacist culture. Can you think of examples of Settler Colonialism from Oregon’s history?

Maria Lugones (she/her) was an Argentine feminist philosopher who explored White Supremacy, gender, and decolonization (figure 5.16). She theorized that gender and the “correct” performance of gender were used as a tool of colonialism that marginalized Indigenous people by narrowly defining a proper person. She also suggested that descendants of settlers can participate in decolonization by understanding and addressing the ways we are implicated in the legacy of settler colonialism.

Decolonization has multiple interrelated meanings. It began as a description of a political process that included a transfer of power back from a colonial government to an indigenous one. For example, India became independent from the British Empire in 1947. For those who have benefited from colonization, decolonization has also come to mean a personal divestment of colonial power across structural, disciplinary, cultural, and interpersonal domains of power. This can mean letting go of internalized ideas of superiority, recognizing broken treaties and agreements, and, in some cases, actually compensating the descendants of colonized people for stolen resources or giving them their land back. For example, in 2021, the trustees of the North Coast Land Conservancy returned 18 acres to the Clatsop-Nehalem People at the mouth of the Neacoxie River, just north of Seaside, Oregon (figure 5.17).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MKNNpSm3g90

Decolonization also refers to a cultural process of identifying and challenging cultural domains of colonial power so that pre-colonial ways of being and knowing can be reclaimed, recovered, and reimagined. In the Americas, descendants of colonized people are engaged in conscious efforts to recover precolonial ways of healing, food production, and governance, as well as recovering language, art, religion, and ways of relating to each other and the environment.

Social scientist Lucas Ballestin (he/him) describes the dominant gender binary as a colonial object (Ballestin 2018) or as a specific left-over of the institution of colonialism and the consolidation of power and social control in Europe in the 18th century. In the next section, we will see how indigenous people are decolonizing gender and sexuality by reclaiming and recovering traditional genders and sexualities.

Impacts on Indigenous Genders and Sexualities

Many societies have defined norms around sexuality and gender expression that also allow for specific cultural spaces that accommodate multiple genders and sexualities. Many religious systems, including pre-Christian European religions, recognize deities that are gender fluid and or gender expansive. People who embody these characteristics are recognized within their cultures as reflections of aspects of the deities or of the cosmos itself and, as such, are essential to society.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=n8O-BwZi7QQ

Muxes (pronounced MU-shays) are a recognized third gender among the Zapotec people in Oaxaca, Mexico. Like many third genders, Muxes play an important role in the cultural life of their community. They preserve and celebrate traditional dress, language, and ceremonial traditions. Muxes are often skilled artists and entertainers and are generally beloved within their communities.

While the rigid gender binary of heteropatriarchy has been widely adopted in Mexico, the Muxes provide a cultural reminder of a pre-colonial matriarchal identity that includes an acceptance of gender fluidity, priests who dressed in women’s clothes, and non-binary, genderfluid deities. Muxes are not just keepers of the past. They also embody a vibrant vision of decolonization and Indigenous empowerment (figure 5.18).

Hijras (pronounced HIJ-ruhs) have been widely referenced in Hindu literature dating back to the 4th century B.C. and have maintained a constant, sometimes marginalized presence in Hindu society. Hijras experienced extreme persecution under the British Empire. Despite this marginalization, Hijras continue to play important roles in Hindu religious ceremonies, including the blessing of marriages and births. Hijra ashrams operate as religious orders and as refuges of relative safety where people assigned male at birth can embody an expansive third gender (Nanda 1998).

In contemporary India, Hijras, along with gay men and lesbians, are still subject to violence and persecution. However, because of their visibility and activism, Hijras are successfully challenging rigid gender norms (figure 5.19). In 2014, the Supreme Court in India responded to Hijras’ activism by creating a legal designation of the third gender. This designation also extended to include other transgender, non-binary, and intersex people. Pakistan, Nepal, and Bangladesh also recognize a third gender. The activism has not stopped with this win. The colonial-era law prohibiting sex between people of the same gender was struck down in 2018 (India court legalizes 2018). However, same-sex marriage has yet to be legalized.

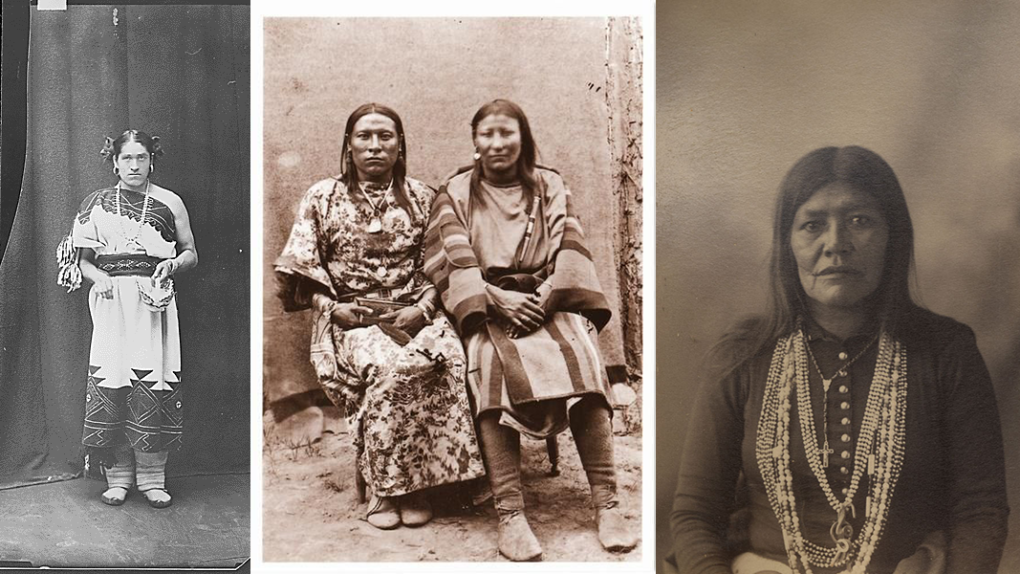

Two-spirit. The Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwa) term niizh manidoowag translates to English as “of two spirits” and traditionally refers to a gender-expansive identity encompassing both male and female qualities or a third gender since their emergence in contemporary Indigenous culture in the 1990s (Montiel 2021). Many transgender, non-binary, and same-sex-loving Indigenous people of North America have embraced the identification of Two-spirit. As with Hijra and Muxe identities, this contemporary iteration of a traditional third gender reaches back to more expansive pre-conquest cultural formations of gender and sexuality and also references the spiritual implications of gender and sexuality (figure 5.20).

The contemporary usage of Two Spirit also highlights the importance of language preservation in recovering pre-conquest culture and ingenious ways of being (Smithers and Runner 2022). There are also many other culturally specific genders and sexual identities names that indigenous people have used to describe themselves, including Nadleehi (“one who changes/who is at war”), Tasta-ee-iniw (“a person in between”), and Napêhkân (“one who acts/lives as a man”) (BigEagle 2023). Non-indigenous people should refrain from assuming that someone identifies as Two-spirit or any other identity and always refer to people in the way they ask.

Muxes, Hjiras, and Two-spirit people, along with many other third-gender, fourth-gender, transgender, non-binary, and same-sex-loving people in previously colonized societies, are reclaiming and reimagining traditional cultural norms around gender and sexuality. Their communities are sites of collective cultural resistance in the face of historic oppression. Within their communities, they are keepers of a vital connection to pre-conquest culture and evidence that expansive constructions of gender and sexuality are possible. They also point us toward more equitable and inclusive systems of power outside of White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, Heteropatriarchy, and Capitalism.

Ultimately, whether individuals within an unequal system of power conform to gender norms or subvert them, unequal systems of power continue to operate until they are dismantled by collective action. The final section of this chapter explores how coalitions of marginalized people can shift the balance of power toward justice and equality.

Learn More: Decolonizing Gender

Learn more about Two-Spirit People [Website].

Learn more about Muxe: Third Gender: An Entrancing Look at Mexico’s Muxes [Streaming Video].

Learn more about Hijras: Being Laxmi: ‘I belong to the hijra, the oldest transgender community’ [Streaming Video]

Learn more about Indigenous genders and sexualities [Website].

Learn more about decolonizing gender: Decolonizing Queerness: Celebrating the Power of My Babaylanic Voice [Streaming Video].

Real But Not True: Binary Gender

Let’s consider how what you are learning about Indigenous Genders and Sexualities demonstrates that binary gender is socially constructed (not true) and has real-life consequences (real).

The tools of sociology include:

- Sociological Imagination

- Research-based Evidence

- Social Theory

The European colonization of the Americas was a violent process that resulted in the death of 90% of the pre-conquest Indigenous population, the transformation of the land and natural resources previously held by Indigenous societies into private property held by European settlers, and securing territorial control for colonizing empires. This conquest replaced matriarchal cultural practices and nonbinary gender norms with heteropatriarchy, a system of power in which cisgender and heterosexual men have authority over everyone else.

We can recognize that socially constructed meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences are not universally true when we can demonstrate that they:

- Change over time

- Are not the same in all societies

- Are imposed, enforced, reproduced, negotiated, or challenged through social interactions.

There are a multitude of examples of nonbinary gender constraints.

- Many societies have defined norms around sexuality and gender expression that also allow for specific cultural spaces that accommodate multiple genders and sexualities. Many religious systems, including pre-Christian European religions, recognize deities that are gender fluid and or gender expansive. People who embody these characteristics are recognized within their cultures as reflections of aspects of the deities or of the cosmos itself and, as such, are essential to society.

- Muxes, Hjiras, and Two-spirit people, along with many other third-gender, fourth-gender, transgender, non-binary, and same-sex-loving people in previously colonized societies, are reclaiming and reimagining traditional cultural norms around gender and sexuality. Their communities are sites of collective cultural resistance in the face of historic oppression. Within their communities, they are keepers of a vital connection to pre-conquest culture and evidence that expansive constructions of gender and sexuality are possible. They also point us toward more equitable and inclusive systems of power outside of White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, Heteropatriarchy, and Capitalism.

The real social consequences of binary gender:

- Intimate partner violence, binary gender norms, and gender inequality exist because they work to establish and maintain heteropatriarchal arrangements of power.

- Heteropatriarchal societies tend to marginalize people whose gender presentation differs from their assigned gender and exclude transgender and nonbinary from full participation in society.

As you continue to work through this book, be on the lookout for other examples of socially constructed meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences and for the ways that tools of sociology can be used to reveal them as social constructions that are not universally true, but have real consequences.

Let’s Review

Licenses and Attributions for Gender in Global Systems of Power

Open Content, Original

“Gender in Global Systems of Power” by Dana L. Perterman and Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Real But Not True: Binary Gender” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.14. “The White Supremacy Iceberg” by Nora Karena and Mindy Khamvongsa, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Real But Not True Puzzle Images” by Nora Karena and Katie Losier are licensed under CC BY 4.0

“Gender in Global Systems of Power Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.12. “Professor Sylvia Tamale speaking at the Africa Feminist Forum, East Africa Gathering- September 2022 in Kampala, Uganda” by Sunshine Fionah Komusana is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 5.20. Photo of We’wha, Osh-Tisch, Dahteste by John K. Hillers (Image Courtesy of: Smithsonian Institute/John H. Fouch/F.A. Rinehart, Image Courtesy of Omaha Public Library) is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Heteropatriarchy” definition by Valdes (1996) is included under fair use.

Figure 5.13. “Video captures neo-Nazis interrupting drag reading hour” by CNN is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.15. The Matrix Of Domination And White Supremacy is adapted from the work of Patricia Hill Collins (1990) by Nora Karena and is included under fair use.

Figure 5.16. Photo of Maria Lugones is included under fair use.

Figure 5.17. “Clatsop-Nehalem Tribes’ Return of Ancestral Land” by Oregon Public Broadcasting is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.18. “Comunidad muxe de Oaxaca” by NotimexTV is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.19. “A group of Hijra in Bangladesh” by USAID – USAID Bangladesh is in the Public Domain.

“Being Laxmi: I belong to the hijra, the oldest transgender community” by The Guardian is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

“Third Gender: An Entrancing Look at Mexico’s Muxes” by National Geographic is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

“Know Your African Feminists: Dr Sylvia Tamale” by African Feminist Forum is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

“Decolonizing Queerness: Celebrating the Power of My Babaylanic Voice, John Ray Hontanar, TEDxUPV“by TEDx Talks is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

an acronym that stands for Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer, Intersex, and Asexual, Plus a continuously expanding spectrum of gender identities and sexual orientations.

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

refers to gender identities beyond binary identifications of man or woman/masculine or feminine.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

refers to a person’s personal and interpersonal expression of sexual desire, behavior, and identity.

a systematic approach that involves asking questions, identifying possible answers to your question, collecting, and evaluating evidence—not always in that order—before drawing logical, testable conclusions based on the best available evidence.

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

(a merging of the words heterosexual and patriarchy) is a system of power in which cisgender and heterosexual men have authority over everyone else. This term emphasizes that discrimination against women and LGBTQIA+ people is derived from the same sexist social principle (Valdes, 1996).

is an unequal system of power that relies on white supremacy to justify removing established indigenous residents of colonized territory so that the land can be occupied by settlers and its resources used for the benefit of the occupying power.

the way our gender identity is expressed outwardly through clothing, personal grooming, self-adornment, physical posture and gestures, and other elements of self-presentation.

is an interdisciplinary approach to issues of equality and equity based on gender, gender expression, gender identity, sex, and sexuality as understood through social theories and political activism (Eastern Kentucky University, n.d.)

a complex competitive economic system of power in which limited resources are subject to private ownership and the accumulation of surplus is rewarded.

literally the rule of fathers. A patriarchal society is one where characteristics associated with masculinity signify more power and status than those associated with femininity.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

the unequal distribution of power and resources based on gender.

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

describes people who identify as the same gender they were assigned at birth.

a complex system of racist power that is based on discredited racist enlightenment-era social science and constructed through policies and practices that privileged white people over people of other races, based on the racist ideas that that there are meaningful differences between people in different racial categories, that White people are physically and culturally superior, and that they are therefore entitled to dominate other people in other racial categories.

a group’s shared practices, values, beliefs, and norms. Culture encompasses a group’s way of life, from daily routines and everyday interactions to the most essential aspects of group members’ lives. It includes everything produced by a society, including social rules.

(multiple interrelated meanings) (1) A political process that included a transfer of power back from a colonial government to an indigenous one. For example, when India became independent from the British Empire in 1947. (2) For those who have benefited from colonization, decolonization has also come to mean a personal divestment of colonial power across structural, disciplinary, cultural, and interpersonal domains of power. (3) A cultural process of identifying and challenging cultural domains of colonial power so that pre-colonial ways of being and knowing can be reclaimed, recovered, and reimagined.

a limited system of gender classification in which gender can only be masculine or feminine. This way of thinking about gender is specific to certain cultures and is not culturally, historically, or biologically universal.

a process of social exclusion in which individuals or groups are pushed to the outside of society by denying them economic and political power (Chandler & Munday, 2011).

people with differences in sexual development (DSD) sometimes identify as intersex.

an awareness of the relationship between a person’s behavior, experience, and the wider culture that shapes the person’s choices and perceptions. (Mills 1959)