5.5 Shifting Power

“Power concedes nothing without a demand.”- Frederick Douglas, 1857 [Website]

Recall from our earlier discussion about intimate partner violence that a survivor-led social movement, sometimes called the “Battered Women’s Movement,” successfully changed how communities respond to IPV by introducing, not only new laws but new ways of thinking about IPV, like the Wheel of Power and Control (figure 5.1). With all this success, why is IPV still a serious social problem? Why are so many people still trapped in violent relationships? New laws and new ideas about violence in relationships are important steps towards ending IPV, but as long as unequal systems of power exist that rely on violence to enforce heteronormative gender norms, as do White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, Heteropatriarchy, and Capitalism, IPV will be with us.

So far, this chapter has explored how gender works to create power within unequal systems of power. In this section, we will learn about the drivers of social change. We will pay special attention to coalitional social movements that build collective power to bring about social change.

Social Change

All societies change in response to changing conditions. New technology, changes in population, changes in the environment, and changes to social institutions, like governments and religions, are common drivers of social change. For example, changing technology during the industrial revolutions of previous centuries and the current cyber-revolution have radically transformed the way people work, our educational systems, our family structures, our communities, and our relationship to the earth and its resources.

Sociologists study social change from a variety of perspectives. Karl Marx, for example, was concerned with theorizing about the conditions necessary for a large-scale social change from capitalist to socialist economies. His theories form the foundation of conflict theory, covered in Chapter Four. Recall that conflict theory identifies social inequality as a driver of social change. Sociologists who study gender look at relationships between social change and gender roles, gender identities, and gender inequality.

Changes in gender roles during and after World War Two is a rich case study for understanding how gender roles can change. During the war, the majority of people serving in the U.S. military were men. During the war, women’s participation in the workforce increased by 50% because the essential jobs that middle-class men vacated were taken up by middle-class women (Rose 2018). With this came a significant increase in women’s incomes. As women began to take over the jobs traditionally considered the domain of men, it was no longer a social taboo for middle-class women to work outside the home and earn money.

This change in gender roles was only temporary, however, and masculine social dominance was maintained after the war, as women were laid off from those jobs, and many had no choice but to return to unpaid labor caring for their husbands and children (figure 5.21). It was not until the women’s movement and second-wave feminism of the 1960s and 1970s, which took inspiration from civil rights movements that middle-class women began to seriously challenge heteropatriarchal systems of power in the workplace.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlnH6V83QRA

Similarly, changes in medical technology and changing understanding of gender identity have led to increased access to gender-affirming medical care. There are currently more than 1.5 million people in the U.S. who identify as transgender (HRC n.d.), and most respondents in a study by the Williams Center believe that the U.S. is becoming more tolerant of transgender gender people and that the U.S. should “do more to protect transgender people” (Taylor 2017). At the same time, political reaction to this change has created a significant increase in anti-transgender rhetoric and legislation.

Profound social changes can happen when social conditions change, like new technologies, environmental changes, or wars. Social change can also be created by social movements, like the civil rights and women’s movements in the mid-20th century.

Social Movements

Donald Trump was elected in 2016 on a platform of proposed policy initiatives that included overturning Roe v. Wade and rolling back civil rights. In response, more than 470,000 people participated in the Women’s March in Washington, D.C. (figure 5.22). This demonstration was one of more than 640 demonstrations globally in January 2017, including a gathering of 100,000 people in Portland, Oregon (Britannica, T. Information 2024).

The U.S. marches were organized by a broad coalition of political organizations. These events were powerful demonstrations of passion and political will around human rights, gender equality, and environmental justice, as well as important base-building opportunities for social justice leaders. While the march was called a social movement, it was actually more of a demonstration of the collective power of multiple institutionalized social movements.

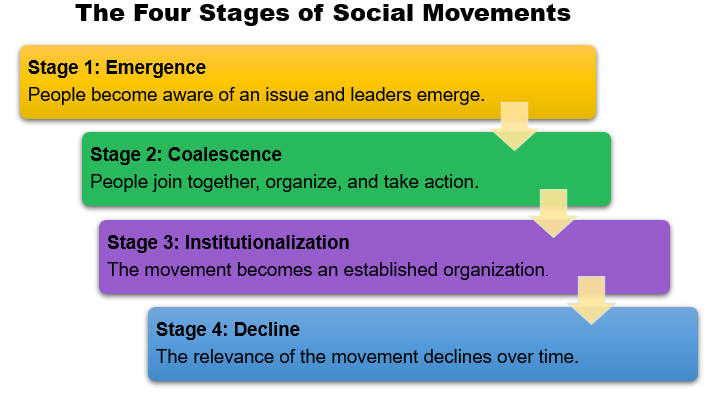

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups that strive to work toward a common social goal. Movements can happen locally, at the state and national level, and around the world. Let’s look at examples of social movements, from local to global. Sociologists study the lifecycle of social movements—how they emerge, grow, and, in some cases, die out. Blumer (1969) and Tilly (1978) outlined a four-stage process, as shown in figure 5.23.

In the emergence stage, people become aware of an issue, and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage when people join together and organize to publicize the issue and raise awareness. In the institutionalization stage, the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism: it is an established organization, typically with a paid staff. When the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or when people fall away and adopt a new movement, the movement falls into the decline stage.

As the example of shifting gender norms during war demonstrates, systems of power can be remarkably resilient in the face of social change. In that case, gender norms temporarily shifted to accommodate changing social conditions, but the unequal systems of power in which those norms continued to operate.

Throughout history, we can identify progress towards more inclusive, expansive, and equitable systems of power met with successful attempts to maintain existing oppressive systems. As soon as reproductive freedom was granted to pregnant people by the Supreme Court in 1973, people empowered by the gendered system of power that restricted pregnant people’s reproductive autonomy doubled down in their efforts to see the ruling overturned. In 2023, masculine dominance over pregnant people was restored when a pregnant person’s constitutional right to terminate a pregnancy was struck down, even though most people in the U.S. believe that the choice to terminate a pregnancy should be legal in most cases (Hartig 2022).

Reactionary social movements, like the anti-abortion movement, try to block social change or reverse social changes that have already been achieved. The recent anti-transgender backlash, which includes banning books with gay and transgender characters, attempts to shut down or restrict drag performances, and an avalanche of anti-transgender legislation, can be considered a reactionary movement whose goal is to block the social changes and maintain heteropatriarchal dominance.

De-centering heteropatriarchy

“The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” – Audre Lorde, 1984

Imagine a room full of wealthy white cisgender men sitting in a circle trying to “solve” White Supremacy, Settler Colonialism, Heteropatriarchy, and Capitalism by themselves. Given what you are learning about how unequal systems of power work, how would they go about dismantling their own dominance and power? How would they measure the success of these efforts? What new system of power would they construct? What would motivate them to even consider such a project?

Now imagine a circle of People of the Global Majority that includes queer, transgender, and non-binary people with the same goal. How different would their strategies be? How would they measure success? How might they reimagine power and build collective power for a more just world? How different might these approaches be? Who do you think might be more successful?

The truth is that the colonial U.S. was an effort by white men to create a more just society (figure 5.24). However, because African Americans, Indigenous Americans, and women of all races were deliberately excluded from full inclusion in the inalienable rights granted to “all men,” and because the humanity of LGBTIA+ people was left unaffirmed, the founding fathers freed themselves from the control of the British Empire, but reproduced heteropatriarchal, white supremacist, settler colonialist, capitalists systems of power, and so missed the mark of “liberty and justice for all.” Contrast that incomplete revolution with the ongoing struggle for civil rights in the U.S.

Aldon Morris (he/him) researches the origins, nature, patterns, and outcomes of global movements that have successfully resisted and overthrown systems of oppression and injustice. Morris argues that the mobilization of the Black community’s internal resources, knowledge, power, and skill were critical drivers of both the 20th-century civil rights movement and the 21st-century Movement for Black Lives.

In both cases, specific systems of domination were identified by members of oppressed communities, who also planned and executed direct action and achieved change in the form of both public policy and public sentiment. These community-based approaches center the collective agency and lived expertise of people marginalized within existing oppressive systems, and create a new political base for powerful collective action (Morris 2021).

The intersectionality of Black feminism and the coalitional sensibilities of other third-wave feminisms (Chapter Four) have also produced powerful movements for social change in the 21st century. For example, the prison abolition movement, which gained national attention during the 2020 protests for Black Lives, was the result of decades of coalitional organizing led by women and queer people of the global majority, whose communities have been most impacted by state violence, in the form of drug wars and racist policing in under-resourced communities.

So what, then, is the role of people empowered by systems of power in revolutionary movements for intersectional gender equality and gender expansiveness? For some, it can start with getting comfortable with being uncomfortable with what we learn about our socialization. It can also include clarifying our motivations and asking why we are willing to work toward dismantling a system of power that privileges us and finding ways to use our privilege, access, and resources to shift the balance of power in favor of marginalized people.

For all of us, dismantling unequal systems of power requires honoring the specific knowledge of people who are marginalized by unequal systems of power and taking our lead from them in movements to shift power toward a more just society.

LEARN MORE: Prison Abolition

Prison Abolition. For an introduction to the ideas behind the social movement to abolish prisons, watch Visions of Abolition [Streaming Video]. Can you imagine alternatives to prisons?

Let’s Review

Looking Through the Lens: The Matrix of Power and Intimate Partner Violence

In this activity, we’re going to use the Matrix of Power to examine Intimate Partner Violence and understand how violence operates in multiple domains to reinforce gender in unequal systems of power.

Step One.

Reflect on what you’ve learned about violence and power as you read this:

Have you ever heard someone ask why victims of abuse have a hard time getting away from their abusers? A common question asked of people who are abused by an intimate partner is, “Why don’t you just leave?”

Advocates and allies of survivors of intimate partner violence argue that this is the wrong question. Instead, we can ask, Why does an abusive person continue to harm their intimate partner? or What are the structural and social barriers that keep someone from feeling like they can leave? The conditions that keep people from leaving abusive relationships are complex and can include a lack of physical and social resources, shame, and fear of harm to themselves, their children, pets, family, or treasured possessions.

Cultural norms about gender and violence can also be a barrier to freedom for people in abusive relationships. For example, heteropatriarchal religious traditions require that wives be submissive to their husbands. Additionally, it is acceptable in some heteropatriarchal societies for husbands to use physical and/or emotional violence to control their wives and for parents to use the same to control their children.

Many survivors of IPV report that in order to survive, they spend great effort trying to avoid punishment by complying with their abuser’s demands. Finally, we can’t overlook the soul-crushing demotivation that can come from experiencing a repeating cycle of alternating violence and affection at the hands of an intimate partner (National Domestic Violence Hotline n.d.). This complex set of rewards and punishments operates across multiple domains of power to maintain an abuser’s power and control over their victims.

Step Two.

(Note: This activity uses they/them pronouns for the victim because anyone can be abused—however, many of these activities are enabled by masculine privilege, and men who are abused are often viewed as feminized.)

Instructions: Use the Matrix of Domination (Figure 5.4) to determine which domain of power applies to each example of intimate partner violence from the Wheel of Power and Control (Figure 5.1) Choose the number that corresponds to the domain of power that best matches the example of intimate partner violence.

Key:

1 = Structural – The power to rule

2 = Disciplinary – the power to punish and reward

3 = Hegemonic (Cultural) – the power to influence

4 = Interpersonal – the power of self-determination

Examples of intimate partner violence:

1 2 3 4 Making and/or carrying out threats to do something to do physical harm

1 2 3 4 Threatening to leave

1 2 3 4 Threatening to commit suicide

1 2 3 4 Threatening to report them to Child and Family Services

1 2 3 4 Threatening to report them to the police

1 2 3 4 Forcing them to drop charges

1 2 3 4 Making them do illegal things

1 2 3 4 Preventing them from getting or keeping a job

1 2 3 4 Giving them an allowance

1 2 3 4 Taking their money

1 2 3 4 Hiding Money

1 2 3 4 Making them afraid by using looks, actions, gestures

1 2 3 4 Destroying personal property

1 2 3 4 Abusing pets

1 2 3 4 Displaying weapons

1 2 3 4 Put downs in public

1 2 3 4 Belittle them in private

1 2 3 4 Making them think they are crazy (gaslighting)

1 2 3 4 Humiliating them in public,

1 2 3 4 Making them feel guilty for wanting to leave

1 2 3 4 Treating them like a servant

1 2 3 4 Making all the big decisions

1 2 3 4 Using religious observance to justify abuse

1 2 3 4 Policing gender roles

1 2 3 4 Tell them they are a bad parent if they leave

1 2 3 4 Using the children to relay messages

1 2 3 4 Threatening to take the children away

1 2 3 4 Monitoring what social interactions (i.e., phone and internet usage)

1 2 3 4 Limiting and controlling their social interactions

1 2 3 4 Use jealousy to justify violence

1 2 3 4 Minimize the abuse

1 2 3 4 Say they caused the abuse

Step Three.

Write a brief paragraph or two reflecting on what you have learned about how gender norms are reinforced by IPV and why it is so hard for people to leave abusive relationships.

Licenses and Attributions for Shifting Power

Open Content, Original

“Shifting Power” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Social Movements” is adapted from “The Sociology of Social Movements” by Kimberly Puttman in Inequality and Interdependence: Social Problems and Social Justice, Open Oregon Educational Resources, and is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications by Nora Karena include editing for length and context.

“Looking Through The Lens: Systems of Power and Intimate Partner Violence” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Shifting Power Question Set” was created by ChatGPT and is not subject to copyright. Edits for relevance, alignment, and meaningful answer feedback by Colleen Sanders are licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 5.22. “Women’s March in Washington DC, USA, 2017” by Mobilus in Mobili is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 5.23. “The Four Stages of Social Movements” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.24. “Scene at the Signing of the Constitution of the United States” by Howard Chandler Christy is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.21. “Culture Shift: Women’s roles in the 1950s” by NBC News Learn is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

“Visions of Abolition: Bonus Footage – Extended Introduction” by VisionsofAbolition is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world (Guerrero 20164).

interconnected ideas and practices that attach identity and social position to power and serve to produce and normalize arrangements of power in society.

the meanings, attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture ascribes to sexual differences (Adapted from Conerly et.al. 2021a).

a complex system of racist power that is based on discredited racist enlightenment-era social science and constructed through policies and practices that privileged white people over people of other races, based on the racist ideas that that there are meaningful differences between people in different racial categories, that White people are physically and culturally superior, and that they are therefore entitled to dominate other people in other racial categories.

is an unequal system of power that relies on white supremacy to justify removing established indigenous residents of colonized territory so that the land can be occupied by settlers and its resources used for the benefit of the occupying power.

(a merging of the words heterosexual and patriarchy) is a system of power in which cisgender and heterosexual men have authority over everyone else. This term emphasizes that discrimination against women and LGBTQIA+ people is derived from the same sexist social principle (Valdes, 1996).

a complex competitive economic system of power in which limited resources are subject to private ownership and the accumulation of surplus is rewarded.

purposeful, organized groups that strive to work toward a common social goal.

is a macro-level theory that proposes conflict is a basic fact of social life, which argues that the institutions of society benefit the powerful.

the unequal distribution of power and resources based on gender.

is an interdisciplinary approach to issues of equality and equity based on gender, gender expression, gender identity, sex, and sexuality as understood through social theories and political activism (Eastern Kentucky University, n.d.)

the gender we experience ourselves to be.

describes people who identify as a gender that is different from the gender they were assigned at birth.

describes people who identify as the same gender they were assigned at birth.

a group of people who live in a defined geographic area, who interact with one another, and who share a common culture (Conerly et al. 2021).

describes how multiple social locations overlap and influence each other to create complex hierarchies of power and oppression, and that overlapping social identities produce unique inequities that influence the lives of people and groups (Crenshaw, 1989).

the process of learning culture through social interactions.

a right or immunity granted as a benefit, advantage, or favor. While privileges can be earned in some systems, privileges can also be unearned and based on social location. For the purpose of describing unequal power arrangements in systems of power we will be referring to those privileges that are “unearned advantages, exclusive to a particular group or social category, and socially conferred by others” (Johnson, 2001).

a theoretical framework developed by Patricia Hill Collins (she/her) to describe how power is socially constructed. Hill Collins identifies four domains of socially constructed power, which arrange power and work together to create systems of power (Hill Collins, 1990).