2 Social Media and Relationships

Dana Schowalter

EARLY RESEARCH ON SOCIAL MEDIA INTERACTIONS

Let’s think for a moment about how we show are physically close to someone in the physical/real world. We tend to do things like make eye contact, we nod along as they are talking, we sit/stand close to them, we actively listen and respond to them, we engage in physical touch with handshakes and hugs, we laugh with them. Or if we are upset, we might look away, cross our arms, roll our eyes, or cross our legs facing away from them. In the face-to-faced world, most people think they are pretty good at determining where the relationship stands based on facial expressions, tone, and other nonverbal cues.

These acts of nonverbal communication contribute to a theory called SOCIAL PRESENCE THEORY, or the feeling of intimacy people experience in a conversation. That doesn’t necessarily mean romantic intimacy, but instead the type of closeness you feel (or don’t feel) with another person after a deep and meaningful conversation or interaction. People can experience that sense of intimacy or closeness with friends, family members, coworkers, members of your place of worship, romantic partners, etc.

When people started engaging in written forms of digital communication such as email and text messaging, researchers wondered whether we could recreate that social presence/intimacy we feel in face-to-face interactions when we are communicating using text-based communication that does not allow for the types of intimacy expression listed above.

Early research on social media communication that was text-based (messenger apps and email) suggested that because social media lacks the interpersonal nonverbal cues like physical touch or physical closeness, that it is difficult, if not impossible, to have close relationships via social media. They listed several reasons this would be true:

- QUALITY GAP: This is the idea that we have greater misunderstandings when we can’t hear someone’s tone or see their nonverbal cues. Think of this as sending a text message, and having the reader/receiver of that text message misunderstanding what you meant. For example, think about a time you’ve sent a text message you meant as a joke, and the person misunderstood your joke or sarcasm. Or perhaps you sent a message when you were in a hurry that got right to the point and was short and direct, and despite your good intentions, the person assumed you were being rude. I’m sure it has happened to all of us at some point. This happened to my partner and I recently: I asked him whether he wanted me to join him at an event, but he was slow to respond so I assumed he wanted to go alone. I did not seek clarification and left him alone. In actuality, he was between meetings, did want me to join, and thought I was acting distant because I didn’t want to go. The basic idea here is that because we don’t have as many verbal and visual cues to rely on, we are at a greater risk for having a misunderstanding.

- IDENTITY CUES: Because most of our early social and digital media was text-only (the 90s were a wild time without picture messages and emojis), researchers were interested in how having fewer pieces of information about the author/speaker would impact society. Researchers assumed that because we would not necessarily know the gender, race, class, abilities, etc., of the person sending the message, social and digital media would lead to more equal treatment of all people and a general breakdown of hierarchies that lead to inequality.

So, a lot of the early research on text-based communication predicted we would be misunderstood more often, and that communicating online would lack the types of intimacy we experience in our face-to-face interactions. In other words, they thought it would be hard to have deep, meaningful conversations online without being misunderstood. They also thought that communicating online would lead to less racism, sexism, ageism, and other types of discrimination.

More Recent Research (what we know now):

But, think again about how you make sure people understand your jokes when you text them or send them a quick message on snapchat. We might include emojis or gifs (especially millennials). We might look for contextual clues (for example, was the rest of the conversation we were having serious or light-hearted). We might know someone is regularly joking and assume they are joking again now. We might reply with a “?” to seek clarification. In other words, we find ways to communicate without being misunderstood, and when we are misunderstood, we have created shortcuts in text-based communication to get our point across better. And, if you think about the number of times we are misunderstood via text-based communication compared to the millions of such messages we see and send every year, we are misunderstood very rarely.

Research also shows us that when we receive text-based messages from people we do not know, we tend to look more closely at the message itself for cues. That includes looking closely at the messages themselves for cues on race and gender. So, we might not be able to see the sender in person, but research shows that we still might look for contextual cues, such as a gendered name or a name that would imply a person is from a particular racial background. We might google the name to see if we can find a picture. We might pay attention more closely to the presence of an accent or unique dialect that would give us more information about the sender.

This is all to say that despite our fears that social media would lead to worse communication, more misunderstandings, or less racism/sexism, it turns out that none of these things happened. Despite this, many ideas that we commonly hear about the drawbacks of using social media as a mode of communication are still persist, even though there is little research to back this as being true. The rest of this chapter explores what we now know about forming and maintaining relationships via social and digital media.

SOCIAL MEDIA AND INTIMACY

As we discussed, social media is frequently associated with a lack of intimacy. We commonly hear that social media is for superficial conversations, and these superficial conversations take away from our ability to have real, meaningful interactions in the real world. Or, I often hear that people in my generation and your generation lack basic communication skills in face-to-face settings because we are used to using social media and text-based communication to have conversations. It’s the “kids these days are glued to their phones” bit that permeates our culture. Let’s look at whether these ideas are supported in research. (Spoiler alert: They aren’t.)

- SOCIAL PRESENCE THEORY AS A CONTINUUM: Early research on social presence theory suggested that presence/intimacy existed in face-to-face communication and was largely absent in digital communication. Researchers now views social presence as a continuum, where the focus is not on the presence or absence of intimacy but rather is based on the degree to which emotional connection is felt and the perception of how “present” or “real” the connection with others feels. It is rarely fully present or fully absent, so research tends to focus on factors that can increase or decrease intimacy within digital communication.

- THE COMMUNICATION IMPERATIVE: Researchers found that users are very highly motivated to maximize communication satisfaction and work around barriers so they can engage in clear communication with others. We want to communicate. We want to communicate clearly. We want to be understood and to understand others. So research shows that even when we have misunderstandings via text-based communication and/or social media, we will be motivated to continue communicating until we really understand each other.

- For example, when we risk being misunderstood, we adapt. We might use “lol” or “hahaha” after a sentence to show we are joking. (And interestingly, people tend to use either lol or hahaha exclusively.)

- We might include a gif to show we are being sarcastic. (If you want to know how to pronounce gif, check out this video.)

- Most early research started with the premise that face-to-face communication is the best way to communicate and digital communication was inherently worse. Thinking of digital communication as less effective and inherently worse ignores a number of factors, including:

- How familiar users are with the technology: The more familiar we are with how to use an app or platform, the more likely we are to use it in ways that reinforce our messages. For example, when I taught my mother-in-law to use gifs, a whole new world of communication opened to her, and she now regularly sends them to help aid in the point she is trying to make.

- Whether people know each other already: When we already know the people we interact with on social media, we tend to be better at placing their communication with us in the proper context. We know when they are joking, and we feel comfortable asking if we are not sure.

- Whether users plan to interact again: Users who do not plan to interact again in the future (for example, people in a comment fight on a news article online) are more likely to be direct and engage in harsh communication. People who anticipate meeting and discussing issues regularly (for example, your family members at Thanksgiving dinner) are more likely to at least try to find common ground and communicate effectively.

- Neurotypicality and neurodivergence: When we assume people will understand conventional social cues, we are assuming a neurotypical audience. People who are neurodivergent often use social media and digital communication to get their points across in ways that increase understanding, and social media communication (for example, TikTok subcultures) have increased understanding of neurodivergence, which has increased felt senses of intimacy in communication.

- COMMUNICATION QUALITY: Early research suggested social media communication was superficial, because social media chats can never replace the feeling of giving or receiving a good hug. However, research now shows us that while social media cannot literally give you a hug, that does not mean it is void of meaning. We tend to adapt to engage in emotional communication online, for example, sending someone a well-timed heart emoji or hug gif. We are also able to have complex conversations via social media, and sometimes those conversations are actually more clear and meaningful because we can think of exactly what we want to say and edit our thoughts before we send them. In fact, it is quite common that we engage in meaningful communication online, and we might even be more likely to communicate our real feelings using digital communication because we feel more comfortable sharing when we can fully think about what we want to say and how we want to say it.

- SOCIAL DISPLACEMENT THEORY: Another thing we are often told about social media use is that social media replaces time we would otherwise spend in face-to-face communication with friends and family. But again, research does not support this theory. Instead, research finds two interesting things:

- Social media use does not replace face-to-face time, but it does replace time spent with other forms of media. So, you spend just as much time (or more) with friends and family than you would have before you had a cell phone, but you spend less time watching TV, reading books, going to movies, etc. For me, this means sometimes I scroll TikTok for hours before I go to bed, and sometimes I watch Netflix. My social media usage did not replace any face-to-face interactions, it just replaced watching TV.

- Research shows that social media platforms actually increase support for contact in our pre-existing relationships. So, maybe because you have social media, you are more likely to connect both in person and online with people you might otherwise not keep track of when you go away to college.

Next, let’s look at the role the Internet in general and social media in particular plays in enabling intimacy. Because I’m a professor and professors always use Ted Talks, here is a Ted Talk that discusses research on how the Internet enables intimacy. (HINT: There is a question about this video on your worksheet, so you should actually watch it.)

ONLINE DATING/DATING APPS

Let’s just start by saying that online dating and dating app usage is very common. About 7 in 10 Americans report using a dating app or online dating platform at some point in their lives, with young adults (under age 30) and LGBTQIA+ folks reporting the highest usage. Approximately 20% of current committed relationships and 7% of marriages began from online/app-based platforms.

Online dating has a bad reputation for enabling us to meet a lot of different people, with very few of those interactions leading to committed intimate relationships. And while it is true that many of our online dates don’t lead to committed relationships, it is also true that many of the interactions we have face-to-face also don’t lead to romantic relationships. Online dating also has a bad reputation for allowing catfishing, or the idea that people will lie about their identity to get dates.

So, let’s explore some of the research and facts on online dating.

The PEW Research Center conducts regular polling about views of online dating. For the latest data, check out this link. But to give the highlights:

- 53% of online daters had a positive experience. This statistic varies widely based on demographic information:

- men report more positive experiences than women

- members of the LGBTQIA+ community report more positive experiences than heterosexual people

- more educated and higher income brackets reporting more positive interactions than people with lower wages or high school diplomas)

- Harassment is still quite common on dating apps. About half of users have experienced at least one of the following behaviors:

- Being sent a sexually explicit image they did not ask for

- Had someone continue to contact them after they said they were not interested

- Being called an offensive name

- Being threatened with physical harmWomen, LGBTQIA+ people, and people of color are significantly more likely to experience these behaviors.

- Women are more likely than men to report being overwhelmed by the number of messages they receive.

- Men are more likely than women to report feeling insecure due to the lack of messages they receive.

- Safety is still the top concern for users (especially among women users). Approximately 60% of people overall support requiring background checks before being admitted to online dating apps and platforms.

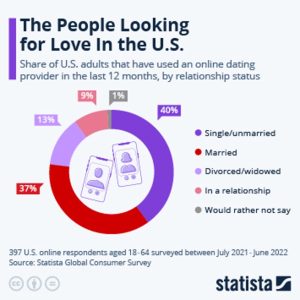

- Here are a few additional graphs with interesting data about online dating:

So, let’s take a look at some of the research!

Do people lie about their identities online?

Overall, no, not really. Most people represent themselves accurately, and this is even true in platforms where lying or misrepresenting your identity is common and/or encouraged (such as Second Life, etc). Even in those settings where people could create avatars that represent any identity characteristics, most people represent themselves and do so fairly accurately.

But, that doesn’t necessarily mean that everything everyone says is 100% truthful. About 53% of people will misrepresent some aspect of their lives, such as their age, weight, occupation, or something similar.

So, why do we engage in this small lies?

First, we make alterations in our profiles to accommodate others (Rowatt, Cunningham & Druen, 1998; Toma and Hancock, 2010). We are more likely to include information that we think a prospective partner will like, even it if isn’t 100% true. So, for example, we might say we are avid outdoors folks who go on hikes ALLLLL the time. If this was true, the trails would be significantly more crowded than they are. So, many people claim to be more active than they are because they believe that is a quality that others would find attractive. Similarly, we tend to include our most attractive photos. (We do this on most of our social media accounts, not just in online dating profiles.) Is it a lie? Technically, yes. But is it the kind of lie that would warrant the concerns of catfishing that people generally have about online dating? Probably not.

Second, we alter profiles to accommodate ourselves. The biggest example of this is altering our profiles because we have a desire to achieve a particular goal, and we assume we will have achieved it by the time we actually meet a perspective partner face-to-face. So, a person might say they weigh less than they do or that they do not smoke when they actually do, but they genuinely assume that by the time they see you in person for the first time, they would have finally lost the weight or quit smoking and would officially be telling the truth.

Also fitting in this category is the idea that we might alter our profiles to accommodate ourselves by only including information we feel it is safe to share to maximize our sense of personal safety online. So, you might say you have one job, but you really have another. And while you know it is a lie, you put it there anyway because you don’t want someone to find you and harass you at that job if things don’t work out. So, is this a lie? Yes. But given that approximately 60% of young women are harassed in online dating sites, it is perhaps not surprising they would choose not to disclose where they work.

Lastly, what we include in an online dating profile might mirror what scholars call a DISEMBODIED IDENTITY. The easiest way to think about this is to think about the different ways you might act and the different piece of information you might disclose about yourself in different contexts. So, how you act around your friends is likely different than the way you act in class, which is probably also different from the way you act around your parents/guardians, which is probably different than the way you act at work, and so on. While you probably are not actively lying to any of these people, you probably are disclosing different information because things that are socially appropriate in one situation might not be socially appropriate in another context. DISEMBODIED IDENTITIES is this concept that we segment our lives and engage in actions based on what we deem to be socially appropriate in various settings with particular groups of people. Researchers who study truthfulness on online dating profiles find that the way we engage our disembodied identities (or, in other words, the way we segment aspects of our lives and experiences) online is not much different than the way we engage in disembodied identities in real life.

Impression Management

Online dating researchers also talk about impression management, or the idea that we often cultivate a particular identity for ourselves online. So, think about your social media profiles and the way you present yourself on Facebook, Twitter, SnapChat, Tinder, etc. It is very likely that none of these platforms represent our 100% totally true and complete identity.

Researchers who study truthfulness in online dating find roughly the same idea in online dating profiles. We might not offer up all information about ourselves in this context, much the same way that we selectively self-disclose in general. So, this means as users you need to determine where the line is between impression management and dishonesty. Is it dishonest to not disclose up front information about your identity? For many people, the answer is probably, “It depends.”

ONLINE DATING AND RELATIONSHIP FORMATION

So, what do researchers say about online dating relationships once they begin?

First, research suggests people who meet online and talk substantially before meeting tend to like each other more and more quickly. For example:

- People who meet online because of one shared interest often assume they must have other shared interests as well (regardless of whether this is actually true), and they therefore tend to report liking each other more.

- We identify good qualities in a person we meet online (for example, that they are smart, funny, responsive to our messages) and we are more likely to assume they have other positive traits even if they do not, and even if these traits would not be replicated in the real world. For example, the person might be quick to respond to your messages because they really like you, and in person they would be very attentive to your needs. It might also be true, though, that they are always on their phone, so when you are talking in person, they might regularly interrupt the conversation to respond to messages they are getting at the same time.

- Because we don’t have as many nonverbal cues when we talk online, we tend to focus more on the message. That means we tend to put more thought into the message we send, and we censor ourselves and deliver our best responses. This may or may not replicate the type of communication we would engage in face-to-face.

Self-Disclosure:

HYPER PERSONAL COMMUNICATION THEORY states that people in online relationship tend to disclose more personal information with each other and do so earlier in the relationship than people who meet face-to-face. Fittingly, couples who meet online tend to get married sooner and are less likely to divorce in the first year.

Dating and Hierarchies

Then there is the question about whether dating online means people will date across lines of attractiveness, race, class, abilities, etc. I’ll let the CEO of OKCupid answer this one:

Social Media and Relationship Maintenance

Because dating online means you have a high number of options for dates available to you, research shows that people who date online tend to have lower relationship satisfaction and lower levels of commitment to their current partners, especially early in a relationship and/or when things get difficult.

High social media use is correlated with more vulnerable relationships, meaning that people who have high social media use are significantly more likely to breakup in the near future. The factors that influence this are:

- Infidelity: This is more likely to occur with high social media use due to the ease of cheating via technology. This can include sharing and/or developing intimate emotional connections with other people.

- Jealousy/Envy: These are common experiences in relationships where one or both partners have high social media use, largely due to the fear that time spent on social media is time spent connecting with people outside the relationship.

- Surveillance: People who are frequent users of social media often report also being more likely to “check up” on the activities of their partners online (looking at their search histories, conversations on various apps, etc). This suspicion also makes them more likely to cross boundaries that exist in healthy relationships where spying on each other is less common.

- Number of accounts: Higher numbers of social media accounts are related to lower commitment levels and lower satisfaction levels in current relationships.

Here are a few other interesting findings:

Social Media and Breakups

We also know that access to social media profiles makes it more difficult to fully separate from a romantic partner after a breakup (Fox & Tokunaga, 2015). Being particular distressed about a breakup (often when we are dumped) is closely associated with more monitoring of that person after a breakup. Studies also show that SnapChat, and in particular the stories and maps functions, tend to be ways that people “get back at” or post “revenge stories” to their exes. The idea that a potential or former partner could be watching is consistently shown to correlate with people actively choosing to alter their social media profiles. For example, people might want to get back at an ex they are really upset with by posting pictures of themselves having fun. The goal would be to send a message that you are doing fine without that person, even if this is not actually true.

Research CONSISTENTLY shows that the healthiest way to get over a former partner is to stop engaging with them on social media in any way, at least for a period of time. So, stop following your ex on social media. You’re welcome 🙂