5.2 Education as a Social Problem

Kimberly Puttman

The stories that open this chapter illustrate core issues in education. Sociologists define education as a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms. On the one hand, the institution is essential. In modern societies, people need the ability to read, write, and think to succeed in their societies. On the other hand, not everyone can attain their educational goals.

As we remember from Chapter 1, a social problem is “a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world (Leon-Guerrero 2018:4). In this case, because not everyone has access to the education that they need to succeed, we experience negative consequences for individuals, families, and even global communities.

The story of modern education is a story of a significant social shift. As the video in Figure 5.1 noted, most people across the globe can read and write, something that wasn’t true even a hundred years ago. Although men and boys historically have had more chances to go to school than women and girls, the gender gap in education is closing around the world (Roser and Ortiz-Espinosa 2016). Recently, evidence shows that young women are more likely to attend and complete college in the United States than young men (Pew Research 2021). These positive results in creating equal access to education don’t tell the whole story, though.

Like every social problem, our social identities and social locations, as discussed in Chapter 2, play a significant role in the kind of education available to us. Social identities and social locations also influence how much school we can finish. When sociologists study education, they find that race, gender, geographical location, socioeconomic status, and all the combinations of these locations have a role in predicting a particular group’s likelihood of succeeding in school.

In this section, we will focus on the dimensions of diversity that students like you are most interested in understanding—education for d/Deaf, neurodiverse, and Indigenous students. However, if you’d like to learn more about how race and gender affect education, you may be interested in this chapter: An Overview of Education in the United States.

5.2.1 d/Deaf and Black: Intersectional Justice

When sociologists examine the social problems of education, they look at who is defining the problem or claim. We examine the evidence that supports the claims. We evaluate what activists and community members suggest can be done about it. We review law and policy changes to understand their consequences. Finally, we explore how changes might feed subsequent social action.

When we examine educational access and outcomes for d/Deaf students in general and for Black and d/Deaf students in general, we see conflicting claims, different outcomes, and unexpected consequences of law and policy changes. This section explores the experiences of being d/Deaf and being d/Deaf and Black to highlight how inequality is intersectional and why intersectional justice is crucial to attaining equity.

Figure 5.3. Being a Deaf Student in a Mainstream School [YouTube]. Please watch the first 5 minutes of this video. What experiences does this student have that are the same or different from yours? Transcript

As we begin our exploration, you may have noticed that we are using d/Deaf as a general term. This unexpected spelling highlights the first conflict in this area. The more common usage of deaf refers to the medical condition of being physically unable to hear. This traditional definition reflects the perspective of doctors and other medical professionals who define deafness as a medical disability needing intervention, treatment, and special support to enable deaf people to function in a hearing world. “The medical model of disability says that people are disabled by their impairments or differences” (Thierfeld Brown 2023, emphasis added). In the medical model, people suffer from deafness.

When the word Deaf is capitalized, on the other hand, it refers to a culturally unique group of people. According to Dr. Lissa D. Stapleton, a Deaf Studies professor, “The upper case D in the word Deaf refers to individuals who connect to Deaf cultural practices, the centrality of American Sign Language (ASL), and the history of the community” (Stapleton 2015:569). In this idea of Deafness, Deaf communities have their own language, culture, and practices different from hearing cultures but just as valuable. This definition uses the social model of disability which says that disability is caused by the way that society is organized (Thierfeld Brown 2023, emphasis added). This model says that a physical limit is only a problem if society doesn’t address the need. If the world were organized to support d/Deaf people and hearing people, we would not see inequality.

We use d/Deaf in this book to acknowledge the complexity of deafness and Deafness and to discuss both a physical condition and a social location.

Figure 5.4. A family signing using American Sign Language. How might using a physical language rather than one you hear change your culture? Image description

You may be d/Deaf or know people who are d/Deaf, like the people in Figure 5.4. In that case, you can draw upon your own experiences. If you aren’t d/Deaf, the video in Figure 5.3 might help you. Being d/Deaf impacts your whole life, but let’s focus on how it changes your education experience.

Dr. Stapleton and her colleagues explore why college graduation rates for d/Deaf women of color are particularly low. As of 2017, Only 13.7% of d/Deaf Black women get a bachelor’s degree. In comparison, 26.5% of Black hearing women graduate college (Garberoglio et al 2019). You may remember from earlier chapters that many social problems are intersectional. People experience them differently based on their various social locations. In this case, Dr. Stapleton looks at how gender, race, and d/Deafness intersect to understand these students’ unique experiences. She explains that part of the difficulty for these students is related to being able to be d/Deaf, female, and People of Color. She shares one story about herself and an Asian d/Deaf student:

I have had several one-on-one interactions with Amy over her two years at the institution. She struggled with shifting identities between her life at home and school. At home, her family treated her like a hearing person; she spoke her ethnic language, participated in all her ethnic cultural practices, and used hearing aids. When she came to school, she only signed and did not interact with other Asian students, as most of the d/Deaf students on campus were White. She did not feel hearing, Asian, or d/Deaf enough to fit into the residential or campus community. She struggled. Because of cultural taboos, she was afraid to tell her parents that she needed counseling and was unable to find a counselor to meet her communication needs (simultaneously signing and speaking), so she started to shut down.

The lack of congruency and peace she felt affected her schoolwork, her friendship circles, and now her ability to stay at school because her behavior had become unpredictable and distant. (Stapleton 2015:568)

These stories highlight the experiences of a d/Deaf female Asian student. In some situations, being d/Deaf is the most important part of identity. In others, race is a shared experience of identity. This story shows how inequalities in social location set the stage for social problems in education.

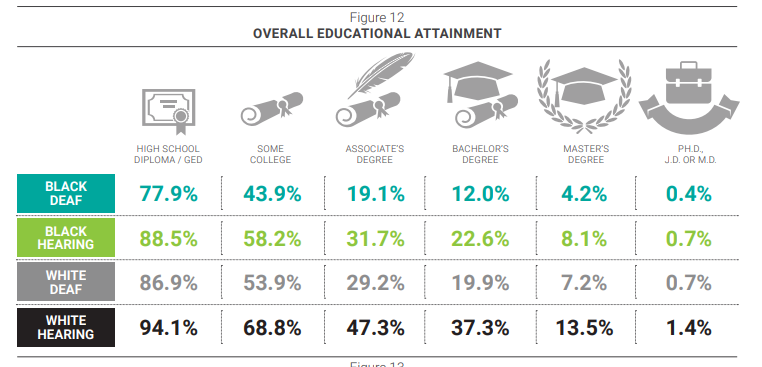

Beyond these stories, though, do we see unequal outcomes in education for d/Deaf students? Let’s look at a small slice of the quantitative data. The table in Figure 5.5 addresses the overall educational attainment for Black Deaf, Black Hearing, White Deaf, and White Hearing students.

Figure 5.5. Overall Educational Attainment for Black d/Deaf, Black Hearing, White d/Deaf, and White Hearing Students. White hearing students have the highest educational attainment in all categories. Black Deaf students have the lowest educational attainment. Image Description

We notice that hearing people have higher educational attainments than d/Deaf people except for the Ph.D., JD, or MD levels, in which Black hearing and White d/Deaf people comprise only .7 percent of each population attained that level of education. Black d/Deaf people had the lowest level of educational achievement of any category.

Audism is one factor in explaining the suffering in these students’ stories and the different outcomes of d/Deaf students. Audism is “the notion that one is superior based on one’s ability to hear or behave in a manner of one who hears” (Humphries 1977:12). Students who are d/Deaf experience discrimination because others assume hearing people are superior. They design the experience of education with hearing people in mind.

In the words of one student:

Society assumes and exerts superiority over their capabilities of hearings. In Deaf schools, deaf youths are [likely] to experience being discriminated against based on their deafness because the culture is too deep-rooted with the belief that deaf people can do what hearing people do, only that they can’t hear.

…In mainstream schools, I know this because I experienced this more than often. Sometimes I have teachers or interpreters who think I need some assistance with what to say. They think they know our needs. Sometimes we will have someone jump in to “help” us communicate. It is very embarrassing when speaking to a hearing student, especially if we are attracted to them and always have interpreters jump in act like we need their help to talk.

Hearing people misunderstood our facial, body and gesture expressions and avoided us; even told us to “dial down.” (SOC 204 student 2021)

A second factor in the experience is racism. Racism starts with the belief that one race is superior to another, most commonly a belief that White people are superior to all other races. We’ll dive deeper into race and racism in Chapter 9, but as we saw in the stories of the d/Deaf students, people who are d/Deaf can experience prejudice based on the constellation of their social locations.

5.2.2 Unpacking Oppression, Seeing Justice: What’s With All the -isms?

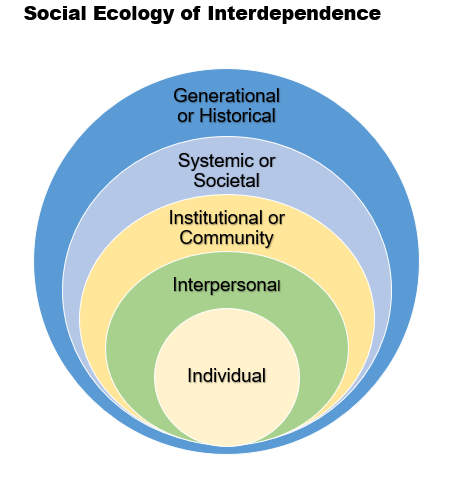

Figure 5.6. Social Ecology of Interdependence: How can we see connections between prejudice and discrimination at all levels of this diagram?

You may have already noticed that we talk about a lot of ‘isms’ in this book: ableism, audism, racism, and sexism, for example. The Wheel of Power and Privilege from Chapter 2 has more of these words.

Ableism starts with the belief that people whose bodies work as expected are better than people who may not be able to see, hear, walk, or have other challenges. People who believe that d/Deaf people are somehow less than hearing people are practicing audism. Racism starts with the belief that one race is superior to another, most commonly that White people are better than people of other races. Sexism starts with the belief that men are superior to women or nonbinary people. Heterosexism centers the value of heterosexual or straight people as better than homosexual, bisexual, or polyamorous relationships. What other words do you know that fit this pattern?

Collectively, these beliefs are known as prejudice. More specifically, prejudice is an unfavorable preconceived feeling or opinion formed without knowledge or reason that prevents objective consideration of an individual or group. While humans appear wired to notice differences as a survival trait, assigning value or worth to those differences is a problem.

Often we have these feelings or beliefs without ever noticing them. When I was considering what to write, the first story that came to mind was, “Imagine that you are White woman, walking alone in the dark on a deserted city street. You might already be afraid. Now, imagine that a Black man turns the corner and is walking toward you. You might feel more afraid.”

I am ashamed that this is my first idea, particularly because I know that most of the time women who are sexually assaulted are harmed by someone they know, most often a partner or ex-partner. And yet, the pattern of belief around White and safe remains in my brain.

Many of us are unaware of these false beliefs. Researchers at Harvard have developed a set of tests that help people see their own patterns of belief. This test is called the Implicit Bias Test. Implicit bias is the hidden or unconscious beliefs that a person holds about other social groups. Implicit means hidden or unspoken. Bias is another word for prejudice. The researchers compare categories of people—women and men, gay and straight, various religions, Arab/Muslim, and others.

Because it is a belief or judgment of a person, prejudice happens internally. It is the first circle in Figure 5.6. However, belief also drives behavior. Harmful action that arises from the flawed belief can be as small as a microaggression, as we explored in Chapter 2. It can be a racial slur or a sexist joke. It can be as violent as someone beating up a transgender person because they think the person is using the wrong bathroom. It can be bombing a Black church, Islamic mosque, or a Jewish synagogue. It can be passing laws that make it illegal to educate entire groups of people. All of these behaviors are discrimination, the unequal treatment of an individual or group based on their status. Discrimination is the second component of audism, racism, sexism, ableism, and the other -isms that people experience.

However, belief and behavior are not the only two levels where discrimination can occur. Discrimination happens in our neighborhoods, schools, governments, and countries. It is rooted in the unequal practices of the past but continues into the present. We will refer to the other levels of discrimination throughout the book.

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and see justice

Unlearning bias starts with seeing it.

- Please take a test or two at Project Implicit. What did your result show?

- Consider your emotional reaction to those results. Some people react very strongly to the test, particularly if it reveals bias. Why might that be?

- What action might you take as a result of this activity?

5.2.3 Neurodiversity

Figure 5.7. What is Neurodiversity? [YouTube]. As you watch the first 5 minutes of this video, consider the experience of this neurodiverse person. How does inequality in education show up for her? Transcript

Activists and scholars notice a parallel between the experiences of Deaf people and neurodiverse people. Deaf people assert that Deaf people form a cultural group. Deafness is not a disability but a common human variation. Neurodiversity activists use a similar argument. To learn more, please watch the first 5 minutes of the video in Figure 5.7.

Neurodiversity is a term that means that brain differences are naturally occurring variations in humans (Walker 2021). Sociologist and autistic person Judy Singer did the initial deep science that supported this term in 1998 (Doyle 2022). The neurodiversity perspective sees brain differences rather than brain deficits. Instead of viewing differences as disordered or needing to be cured, a neurodiverse perspective sees differences as welcome variants of the human population (Walker 2021; Pollack 2009). If you want to learn more, you can read this article about Judy Singer.

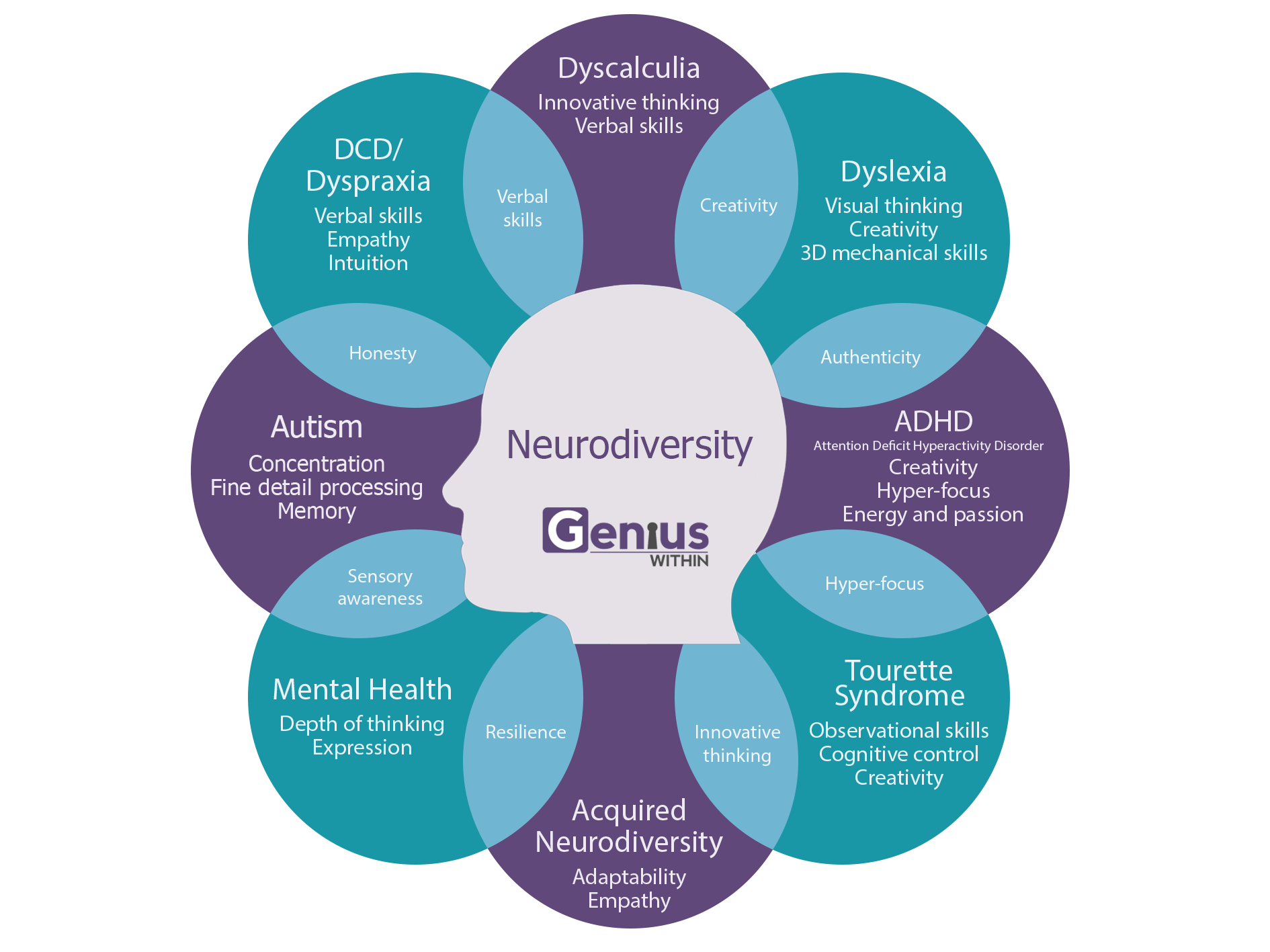

People whose brains are wired differently than expected are called neurodivergent. Neurodivergent people have significantly better capabilities in some categories and significantly poorer capabilities in other categories (Doyle 2020). You may hear many labels and diagnoses that make up neurodivergence: ADHD, autism, Asperger’s, dyslexia, dyscalculia, learning differences, and many more words.

Researcher David Pollack provides a model of neurodivergence in Figure 5.8 which relates several of the labels we listed at the beginning of this section. People experience many different and overlapping learning differences as part of being neurodivergent.

Figure 5.8. Neurodiversity is complicated. Often neurodiversity brings particular strengths and challenges. Why do you think this model focuses on strengths rather than challenges? Figure 5.8 Image Description

As we move from the individual experience to the social experience, we begin to define the particular social problem. Approximately 15 to 20 percent of people worldwide are neurodivergent (Doyle 2020), and this number appears to be increasing. We see that being neurodivergent is not just the experience of individuals. Rather, it is the shared experience of a group, a needed condition for a social problem.

We also see conflict between how people understand and explain neurodiversity. On one hand, we have a medical model, based on pathology or abnormality (Walker and Raymaker 2021). In this model, differences in reading, calculating, writing, or interacting with others is considered a problem, something to be treated or cured.

In the 1990s, adults with these labels began to push back against these categorizations. Their alternate claim was that these conditions should be considered normal human neurology variants. Patient-centered care advocate Valerie Billingham coined the phrase, “Nothing about me, without me” (1998). She was talking about the need to include the patient at the center of decision-making around patient health and treatment choices.

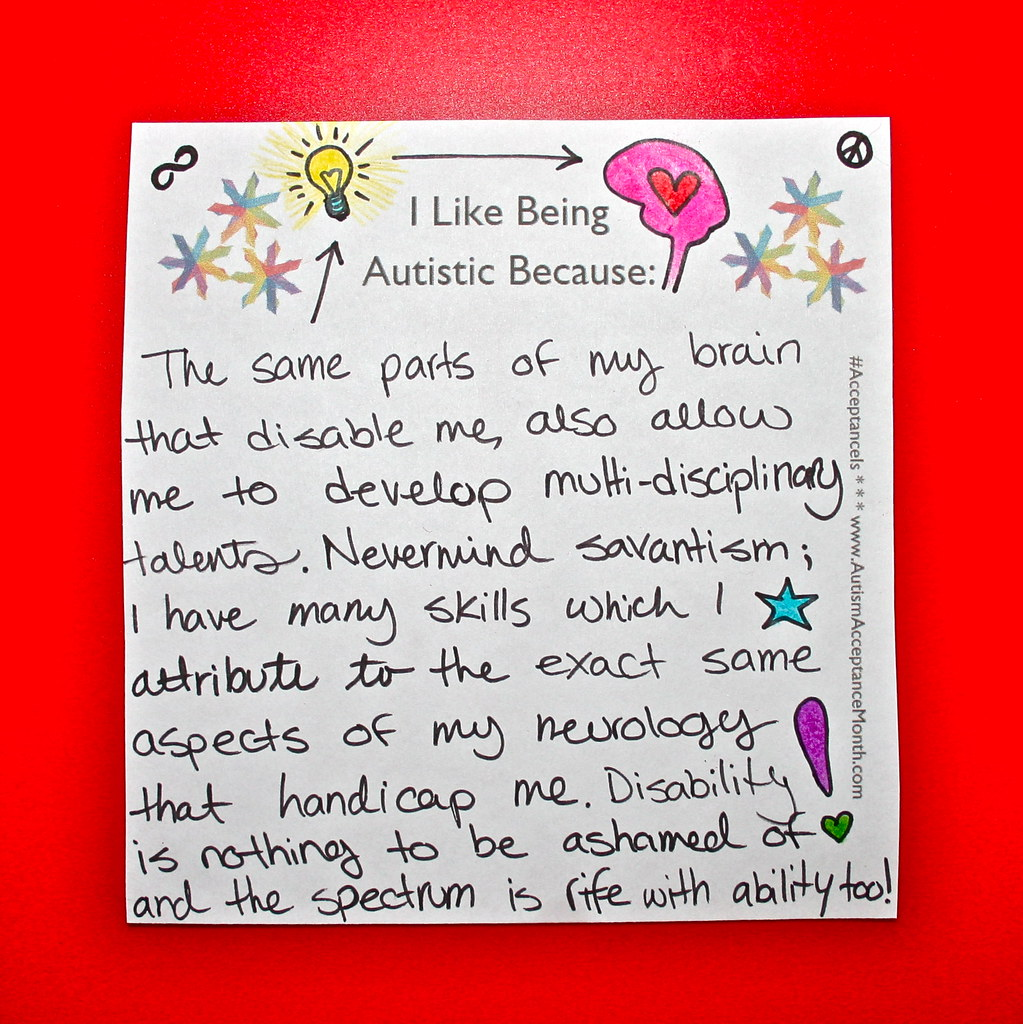

Figure 5.9. Positive experiences of Neurodiversity. How does the phrase, “I Like Being Autistic” challenge your ideas about neurodiversity? Figure 5.9 Image Description

This phrase is used widely today by autism awareness activists, who have expanded the meaning to include the idea that people who are neurodivergent should be the ones describing their own experiences. The letter in Figure 5.9 provides one example of this. People with autism are the ones who should make choices about what they need in order to fully participate in school and in life. They should propose the laws, policies, and practices that make their participation possible.

Some experts see neurodiversity itself is a civil rights challenge. They argue that society privileges people who are considered neurotypical. Not only are neurodiverse people stigmatized with a label that implies disease, symptom, or medical problem, but social institutions themselves are unequal. They propose that we strive for “neuro-equality (understood to require equal opportunities, treatment and regard for those who are neurologically different)” (Fenton and Krahn 2007:1).

Likewise, Nick Walker, a queer, transgender, and autistic scholar, encourages us to see beyond the medical model. She writes:

The neurodiversity paradigm starts from the understanding that neurodiversity is an axis of human diversity, like ethnic diversity or diversity of gender and sexual orientation, and is subject to the same sorts of social dynamics as those other forms of diversity —including the dynamics of social power inequalities, privilege, and oppression. (Walker 2021)

In this brief explanation, we see the shared experience of a group of people. We see disagreement in how we understand the experience of that group. We see unequal outcomes in school and in life. Activists propose changes, and our government enacts legal and policy changes. This activity leads to new formulations of the problem and requests for action. In short, we see a social problem.

5.2.4 Unpacking Oppression and Enabling Justice

I have Asbergers

I am a person who uses a wheelchair.

I’m a crip.

That poor little blind girl….

Are they disabled?

Many of these phrases use everyday language. Some of them focus on the ability or disability. Some of them focus on the person. Some of them reclaim the use of language in new ways. The way that language is changing around ability and disability demonstrates the social construction of a social problem at work.

Some people say that they are “people who use wheelchairs” or “people who are neurodiverse.” They use people first language. Person first language is a way to emphasize the person and view the disorder, disease, condition, or disability as only one part of the whole person (NIH 2022). It focuses on the human being first and the difference second. This language developed in the 1970s and 1980s in response to the language of the time. Before person first language, it was common to hear “a victim of epilepsy” or “that poor blind kid,” phrases which denied the humanity of the person experiencing the condition or illness. In this example, the organization People with AIDS focused on the agency of people with AIDS:

We condemn attempts to label us as “victims,” a term that implies defeat, and we are only occasionally “patients,” a term that implies passivity, helplessness, and dependence upon the care of others. We are “People With AIDS.” (The Advisory Committee of People with AIDS 1983

Some people will say that they are d/Deaf, autistic, or neurodivergent. This is an example of identity first language. Identity first language focuses on an inherent part of someone’s identity, such as deafness or neurodiversity. It is a response to person first language (Brown 2012). Lydia Brown, an Autistic activist, writes:

In the autism community, many self-advocates and their allies prefer terminology such as “Autistic,” “Autistic person,” or “Autistic individual” because we understand autism as an inherent part of an individual’s identity — the same way one refers to “Muslims,” “African-Americans,” “Lesbian/Gay/Bisexual/Transgender/Queer,” “Chinese,” “gifted,” “athletic,” or “Jewish.” (Brown 2011)

Similarly, d/Deaf people often use identity first language to emphasize that being deaf isn’t just a physical condition that indicates a lack of hearing. d/Deaf is also a community and culture with its own language and social norms.

Another group of activists is using the word “crip,” derived from the word cripple, to describe themselves. They fiercely reclaim this word to describe the physical challenges they experience.

Like queer, crip(ple) is a slur that has been reclaimed by many physically disabled people, especially those who also identify as queer. There are a lot of reasons that people identify as crip(ple)s, but like queer, one reason is to have a word that is yours…… It is based in the radical idea that disabled people can be openly disabled and still be deserving of respect. (Strauss 2018)

Crips claim that name as a source of their power.

It’s your turn to unpack oppression and enable justice:

Figure 5.10. In “An Analogy of Ableism [YouTube],” anthropologist Dana Petermann (who is a contributor to the Open Oregon Project) helps us understand what it might be like to live as a human on the imaginary planet Krypton.

- Please watch the video in Figure 5.10.

- Then, pick a condition that people often consider a disability. Imagine that everyone on the planet shared that category. What would that planet be like? What would that planet be like for you?

- Finally, come back to Earth. What would need to change here so that society would support people equitably? The change could be laws, policies, practices, social norms, or individual biases.

5.2.5 Violence and Oppression: Indian Residential Schools

As we continue our exploration of education and inequality, we see that the institution of education can also support violent and oppressive social control. For this, we look at the history of residential schools in the United States and Canada designed explicitly to disrupt the families and the cultures of Indigenous people.

Figure 5.11. Deb Haaland, US Secretary of the Interior, is th first Native American to serve as a cabinet secretary. She is a registered member of the Laguna Puebla tribe.

Deb Haaland, the US Secretary of the Interior, describes this history in the following way:

Beginning with the Indian Civilization Act of 1819, the United States enacted laws and implemented policies establishing and supporting Indian boarding schools across the nation. The purpose of Indian boarding schools was to culturally assimilate indigenous children by forcibly relocating them from their families and communities to distant residential facilities where their American Indian, Alaska Native, and Native Hawaiian identities, languages and beliefs were to be forcibly suppressed. For over 150 years, hundreds of thousands of indigenous children were taken from their communities. (Haaland 2021)

Secretary Haaland, shown in Figure 5.11, also recounts her family’s suffering. She writes, “My great grandfather was taken to Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania. Its founder coined the phrase “kill the Indian, and save the man,” which genuinely reflects the influences that framed the policies at that time” (Haaland 2021). If you would like to learn more about residential schools from those who experienced them, you could watch How the US Stole Thousands of Native American Children

.

Colonizers saw the very existence of Indigenous people as a problem because the Indigenous people inhabited land that the colonizers wanted. They established mandatory residential boarding schools for Indigeous children, a part of a strategy of genocide. Genocide is the systematic and widespread extermination of a cultural, ethnic, political, racial, or religious group. Many Indigenous children died in residential schools (National Native American Boarding School Healing Coalition N.d.). The Federal Indian Boarding School Initiative Investigative Report, released in May 2022, documents the recent findings that at least 500 children were buried in 53 burial sites on residential school properties (Newland 2022:8).

Researchers expect to find even more burials. Recent discoveries in Canada indicate that up to 6,000 First Nations (the Canadian preferred word for Indigenous) children died in Canadian residential boarding schools (AP News 2021). You can read the full Investigative Report if you wish.

These deaths are only the start of supporting the claim of genocide. According to Jeffrey Ostler, a historian at the University of Oregon, claims of genocide are contested by scholars and activists (like many other social problems). However, he provides evidence that the violence was systematic and intentional. To learn more, you are welcome to read Ostler’s article exploring complexity in claims of genocide. In addition, let’s review this history.

The federal report details some of the basic facts. The United States established 408 federal boarding schools between 1891 and 1969. Congress established laws that required Indigenous parents to send their children to these boarding schools (Newland 2022:35). Government records document, “[i]f it be admitted that education affords the true solution to the Indian problem, then it must be admitted that the boarding school is the very key to the situation” (Newland 2022:38). Colonists attempted to destroy Indigenous people and cultures by requiring students to learn English and agriculture, and punishing the children, sometimes with beatings, if they spoke their Indigenous languages or practiced their own religious and spiritual practices. However, Indigenous people survived, reclaimed their cultures and revived their practices over time.

Figure 5.12. Howley Hall, Chemawa Indian School, in Salem, Oregon. What would your life be like if you were required to live at a school whose mission it was to replace your cultural upbringing with an outsider’s way of life?

Oregon shares this painful history. Historians Eva Guggemos and SuAnn Reddick from Pacific University found that at least 270 children had died while at the Chemawa Indian School in Salem, Oregon (Figure 5.12) Most of these deaths were due to infectious diseases. Even in cases where the children didn’t die, colonizers accomplished cultural assimilation, the process of members in a subordinate group adopting cultural aspects of a dominant group.

In this case, the colonizers valued their White European culture as superior to Indigenous cultures and forced other groups to conform. These pictures in Figure 5.13 and 5.14 tell of cultural assimilation at the Chemawa Indian School/Forest Grove Indian Training School.

Figure 5.13. “ A group portrait of students from the Spokane tribe at the Forest Grove Indian Training School, taken when they were “new recruits.” (Francis 2019)

Figure 5.14. “Seven months later — the children pictured are probably the Spokane children who, according to the school roster, arrived in July 1881: Alice L. Williams, Florence Hayes, Suzette (or Susan) Secup, Julia Jopps, Louise Isaacs, Martha Lot, Eunice Madge James, James George, Ben Secup, Frank Rice, and Garfield Hayes.” (Francis 2019)

In the Pacific University magazine, Mike Francis writes about these photos in more detail:

An 1881 photo of new arrivals from the Spokane tribe shows 11 awkwardly grouped young people, huddled together as if for protection in an unfamiliar place. Some have long braids of dark hair; some girls wear blankets over their shoulders; some display personal flourishes, including beads, a hat, a neckerchief.

A second photo of the group is purported to have been taken seven months later….the same children are seated stiffly on chairs or arranged behind them. The six girls wear similar dresses; the four boys wear military-style jackets, buttoned to the neck.

Further, one girl is missing in the second photo — one of the children who died after being brought to Forest Grove… The girl’s name was Martha Lot, and she was about 10 years old. Surviving records tell us she had been sick for a while with “a sore” on her side and then took a sudden turn for the worse.

The before-and-after photos of the Spokane children were meant to show that the Indian Training School was working: Young native people were being shaped into something “civilized” and unthreatening, something nearly European. But today the before-and-after shots appear desperately sad — frozen-in-time witnesses to whites’ exploitation of indigenous children and the attempted erasure of their cultures (Francis 2019).

The Forest Grove Indian Training School, 1880–1885 [YouTube]” tells more of the story for those who wish to learn more.

The function of education in the case of Indigenous boarding schools doesn’t stop with cultural assimilation. White colonizers intentionally used boarding schools to strategically disrupt families and cultures. Beyond that, the government policies and practices related to the education of Indigenous children were part of a wider strategy of land acquisition. As early as 1803, President Thomas Jefferson wrote that discouraging the traditional hunting and gathering practices of the Indigenous people would make land available for colonists. Jefferson wrote:

To encourage them to abandon hunting, to apply to the raising stock, to agriculture, and domestic manufacture, and thereby prove to themselves that less land and labor will maintain them in this better than in their former mode of living. The extensive forests necessary in the hunting life will then become useless, and they will see advantage in exchanging them for the means of improving their farms and of increasing their domestic comforts. (Jefferson 1803, quoted in Newland 2022:21)

By removing people from the land and children from families, the US government made the land available to colonists, who were mainly from Europe, using education as one method of enforcement. Additionally, because children were forcibly removed from their families, they and their descendants lost the rights to inherit any family land that may have remained. This is generational inequality in action. Indigenous students still have the lowest educational attainment of any group in the United States (Martinez 2014).

However, genocide, loss and suffering is not the whole story. Indigenous people use education to heal generational harm. We can see this healing power in efforts to restore and strengthen Indigenous languages. In the following quote, Indigenous biologist, activist, and citizen of the Potawatomi Nation, Robin Wall Kimmerer, links language, culture, and healing, writing that as language is restored, wholeness is also restored:

And so it has come to pass that all over Indian Country there is movement for revitalization of language and culture growing from the dedicated work of individuals who have the courage to breathe life into ceremonies, gather speakers to reteach the language, plant old seed varieties, restore native landscapes, bring the youth back to the land. The people of the Seventh Fire walk among us. They are using the fire stick of the original teachings to restore health to the people, to help them bloom again and bear fruit. (2013:368)

This revitalization of language and culture demonstrates the resistance and resilience of Indigenous people. It also reclaims the power of education to support educational equity and justice:

Dorothy Lazore, a teacher of immersion Mohawk at Akwesasne, describing a basic paradigm shift in how Indigenous children view schooling: ‘For Native people, after so much pain and tragedy connected with their experience of school, we finally now see Native children, their teachers and their families, happy and engaged in the joy of learning and growing and being themselves in the immersion setting.” (Johansen 2004:569)

The genocide of people and culture that occurred when colonists established Indian residential schools created wounds that remain unhealed today. At the same time, Indigenous people are reclaiming the bones of their children, their languages and ceremonies, and even sometimes the schools themselves in order to create a more just world.

5.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Education as a Social Problem

Open Content, Original

“Education as a Social Problem” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.6. “Social Ecology of Interdependence” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Education” definition from Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Cultural Assimilation,” “Discrimination,” “Genocide,” and “Prejudice” definitions from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 5.4. “ASL family” by David Fulmer is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 5.5. “Overall Educational Attainment” from Postsecondary Achievement of Black Deaf People in the United States (p.12) by Carrie Lou Garberoglio, Lissa D. Stapleton, Jeffrey Levi Palmer, Laurene Simms,Stephanie Cawthon, and Adam Sale, National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0.

Figure 5.9. “Photo” by walkinred is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 5.11. “Deb Haaland” by the U.S House Office of Photography is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.12. “Chemawa Indian School” by the Library of Congress is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.3. “Being Deaf in a Mainstream School” by Rikki Poynter is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.7. “What is neurodiversity?” by TheCounseling Channel is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.8. “Neurodiversity is complicated” © Genius Within CIC / Source: Dr Nancy Doyle, based on the highly original work of Mary Colley. All rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 5.10. “An Analogy of Ableism” by Dr. Dana Pertermann is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 5.13. “Image” from A Tragic Collision of Cultures is in the Public Domain. Courtesy of Pacific University Archives. Caption © Mike Francis is included under fair use.

Figure 5.14. “Image” from A Tragic Collision of Cultures. Courtesy of Pacific University Archives. Caption © Mike Francis is included under fair use.