5.5 Education for Transformation is Social Justice

Kimberly Puttman

Unlike many of the social problems discussed in this class, inequality in education is not just a social problem. Transformative education is social justice for our communities. When people can read, write, and reason, they can ask critical questions about their lives. This power to question is a door that opens for justice. To explore this further, we will examine two approaches: education for liberation and crossing the digital divide.

5.5.1 Education For Liberation

Figure 5.22. Paulo Freire was a Brazilian educator. Although he wasn’t a sociologist, his theories and methods transformed how some sociologists think about the transformational possibilities of education.

Education serves a useful function, supporting people in learning and participating with more choices in their societies. Education can also be a way for people to maintain their power because schools can be institutions of social control. Using segregation or separating students into tracks, educational institutions reinforce social patterns of structural racism, sexism, homophobia, and other discriminatory practices. As a third option, education can also serve the purpose of liberation and healing. To explore this approach, we turn to Paulo Freire, bell hooks, and the educators and activists of the Open Oregon Project.

Paulo Freire was an activist and educator in Brazil and internationally from 1940 to his death in 1997 (Figure 5.22). He founded and ran adult literacy programs in the slums of northeast Brazil. When he taught reading and writing, he used everyday words and concepts that his students needed to know to live well, such as terms for cooking, childcare, or construction.

Freire’s most famous book is Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Pedagogy is the art, science, or profession of teaching. Freire is looking at how teaching itself can empower oppressed people. In his book, he condemns the banking model of education, which he defines as “the concept of education in which knowledge is a gift bestowed by those who consider themselves knowledgeable upon those whom they consider to know nothing” (Freire 1970). He argues that the banking model is the most common but least useful form of education. He writes:

Education thus becomes an act of depositing, in which the students are the depositories and the teacher is the depositor. Instead of communicating, the teacher issues communiques and makes deposits which the students patiently receive, memorize, and repeat… [Students] do, it is true, have the opportunity to become collectors or cataloguers of the things they store. But in the last analysis, it is the people themselves who are filed away through the lack of creativity, transformation, and knowledge in this (at best) misguided system. (Freire 1970:72)

In contrast, Freire’s education model emphasizes dialogue, action, and reflection. In dialogue, the students and the teachers discuss what they are learning and how they see things working in the world. Each person contributes from their own experience and knowledge. He writes, “To enter into dialogue presupposes equality amongst participants. Each must trust the others; there must be mutual respect and love (care and commitment). Each one must question what he or she knows and realize that through dialogue existing thoughts will change and new knowledge will be created” (Freire 1970).

This dialogue is essential for learning and transformation but is insufficient as a social force. He argues that teaching and learning also require action and reflection. Engaging in the world and reflecting on what you learned, or praxis, is the true goal of education, creating a more equitable society by taking conscious action. He writes, “It is not enough for people to come together in dialogue in order to gain knowledge of their social reality. They must act together upon their environment in order critically to reflect upon their reality and so transform it through further action and critical reflection” (Freire 1970).

His institute still influences educators and thinkers worldwide about how to use education to promote social justice. If you’d like to learn more about how Freire’s social location influenced his theories, watch this 4:56 minute video, Paolo Freire and the Development of Critical Pedagogy.

Figure 5.23. bell hooks is a Black author, educator, and activist who also argues that education can transform.

Black author and educator bell hooks, pictured in Figure 5.23, built on the work of Paulo Freire, feminist theorists, and her own experiences as a Black woman to expand on this vision of the radical transformative power of education. In her book, Teaching to Transgress, she writes:

For black folks teaching—educating—was fundamentally political because it was rooted in antiracist struggle. Indeed, my all black grade schools became the location where I experienced learning as revolution.

Almost all our teachers at Booker T. Washington were black women. They were committed to nurturing intellect so that we could become scholars, thinkers, and cultural workers—black folks who used our “minds.” We learned early that our devotion to learning, to a life of the mind, was a counter-hegemonic act, a fundamental way to resist every strategy of white racist colonization. Though they did not define or articulate these practices in theoretical terms, my teachers were enacting a revolutionary pedagogy of resistance that was profoundly anticolonial (hooks 1994:2).

She asserts that education can be revolutionary in its approach and outcomes, because students learn in community. Social transformation occurs within the context of an engaged classroom of learners. She writes, “Seeing the classroom always as a communal place enhances the likelihood of collective effort in creating and sustaining a learning community” (hooks 1994:8). Like Freire, she argues that a classroom is a community and that teaching and learning transform the wider world. In this optional video, bell hooks talks about working with Paolo Freire: bell hooks on Freire

.

Each of these scholars and activists argues that education itself, when done in a transformational way, will create change in the student, teacher, classroom, and wider world. With this approach, we see that education becomes a tool for addressing social problems.

Figure 5.24. Open Oregon Educational Resources is a project dedicated to increasing student success in college by producing high-quality, free textbooks and courses for students in Oregon.

In a final example, we explore the project from which this book arose as an exercise in transformation in learning. The Open Oregon Educational Resources organization, whose logo is pictured in Figure 5.24, is a group of educators funded by the state of Oregon to create high-quality educational resources for students. Through developing both textbooks and courses that center diversity, equity, and inclusion, this effort is making course materials more affordable and accessible for many students.

The project allows people normally excluded from research and textbook creation to be included in the process. We are a collective of students, teachers, researchers, activists, and artists weaving our stories into books and courses that reflect and explain our social life. Because we share the work, some of us contributing a lot, and others only a few pages, many of us can tell our stories.

Our radical equity statement is:

The Open Oregon Educational Resources Course and Textbook Development Model seeks to dismantle structures of power and oppression entrenched in barriers to course material access. We provide tools and resources to make diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) primary considerations when faculty choose, adapt, and create course materials. In promoting DEI, our project is committed to:

- Ensuring diversity of representation within our team and the materials we distribute

- Publishing materials that use accessible, clear language for our target audience

- Sharing course materials that directly address and interrogate systems of oppression, equipping students and educators with the knowledge to do the same (Blicher et al. 2023)

Open Oregon’s approach is revolutionary, putting the power to create and share knowledge in the hands of ordinary people. Who would have imagined this in the early days of the first printing press?

5.5.2 Crossing the Digital Divide During COVID-19

When you think about how often you use your phone to find a restaurant, get directions, or look up the actors in your favorite movie, you are using technology to solve problems. However, access to technology is unequal. This inequality is called the digital divide, describing not only internet use but access to computers and smartphones, access to free or low-cost, stable internet, and digital literacy. These three components of devices, access, and effective skills are called the three-legged stool needed to close the digital divide. Individuals need a computer that they know how to use effectively and sufficient quality internet service to participate effectively.

We see the impact of the digital divide locally and internationally. If you would like to learn more about the experiences of other students, watch: The Digital Divide: How does it affect young people in London? [YouTube] It describes the intersection of poverty and technology.

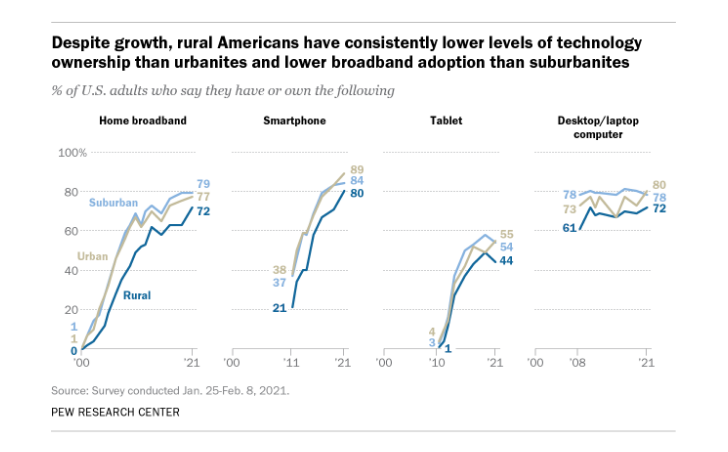

Since the first known usage of digital divide in 1994, researchers continue to examine who is divided. For example, in 2018, Pew Research reported that nearly one in five students couldn’t finish their homework because they couldn’t access the internet (Anderson and Perrin 2018). As you might expect, social location is a strong predictor of who has access to technology and who doesn’t. For example, people in rural areas still own less technology than those living in cities or suburbs (Figure 5.25).

Figure 5.25. Despite growth, rural Americans have consistently lower levels of technology. This graph shows home broadband, smartphone, tablet, and computer ownership in urban, suburban, and rural areas. What is true for you? Image description

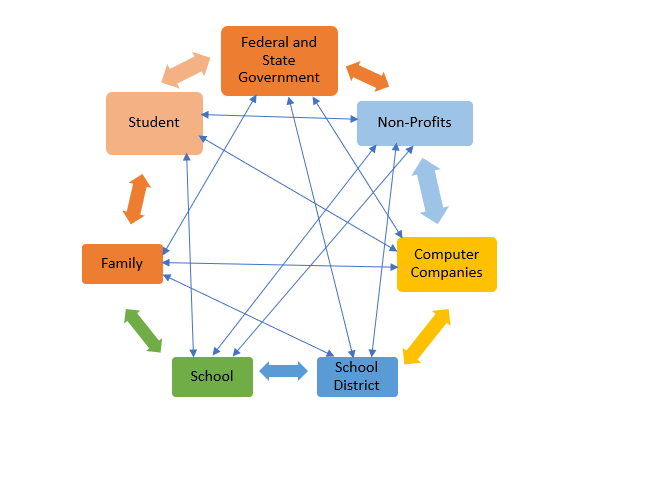

Figure 5.26. Interdependent solutions to educational access during COVID-19. Everyone took action to support education during COVID-19. Who would you add for your own community? Image Description

Because school was online during COVID-19, closing the digital divide was urgent. Institutions and individuals used agency and collective action to promote social justice (Figure 5.26)

For example, the federal government implemented broadband programs allowing families to get internet services at free or low cost. State governments funded internet access for schools and libraries. Local schools purchased computers and hotspots. But technology was only part of the solution.

Nonprofit social service providers highlight digital skills as a support to stabilizing families. Goodwill, for example, hosts a digital learning platform called GFCLearnfree.org, which hosts educational content that helps people learn to use their computers, search for jobs online, and manage their money more effectively. Explore GFCLearnfree.org if you would like to learn more. However, access alone does not help people learn effectively. Some nonprofits are taking a much more integrated approach.

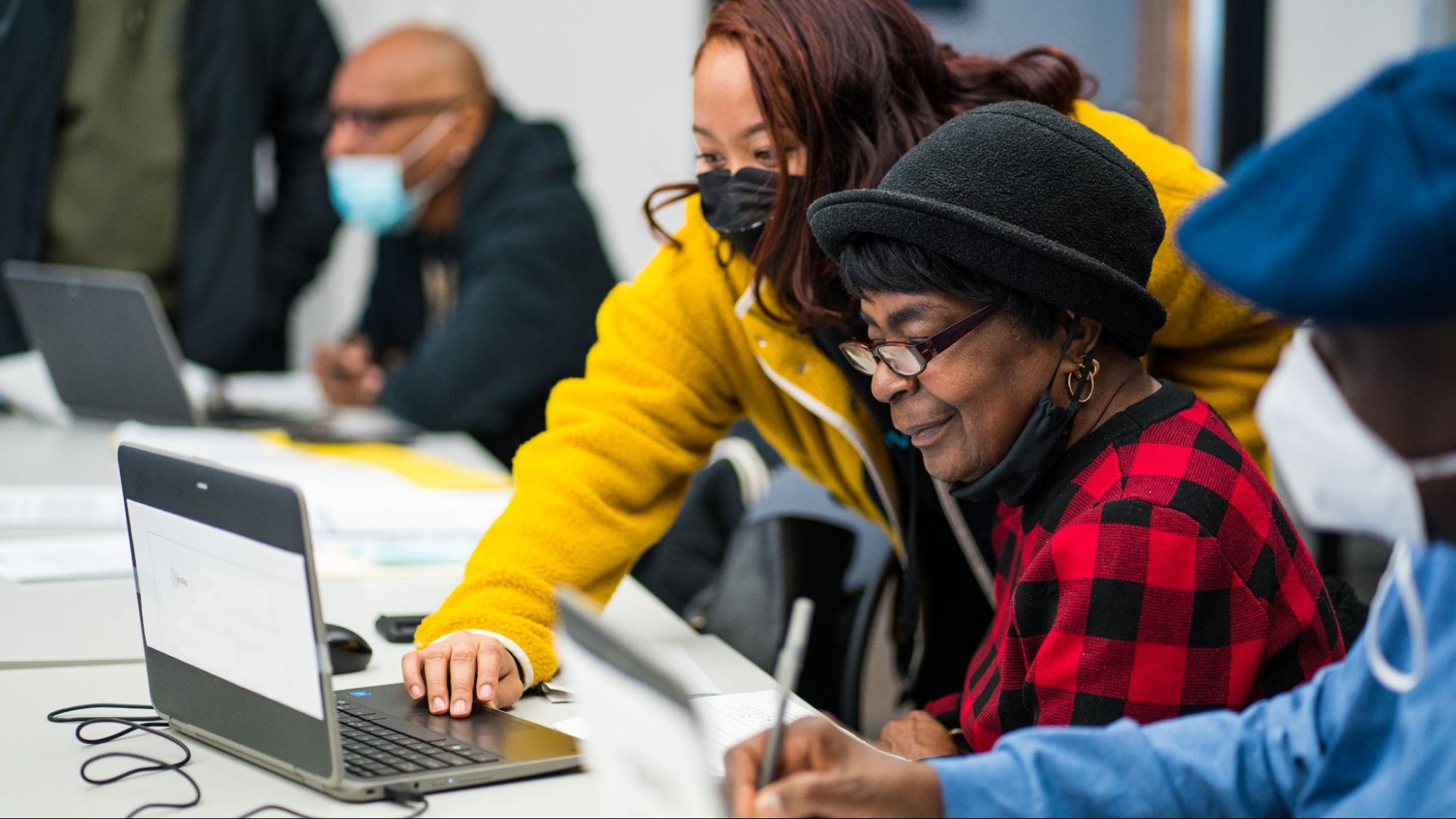

Figure 5.27. Students learning digital literacy skills at EveryoneOn, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Did you have to learn more technology skills so that you could keep learning during the pandemic?

Figure 5.27. Students learning digital literacy skills at EveryoneOn, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Did you have to learn more technology skills so that you could keep learning during the pandemic?

EveryoneOn is a US-based nonprofit that helps create social and economic opportunities in under-resourced communities by providing access to low-cost internet and devices. They also deliver digital skills training. Founded in 2012 to meet the federal government’s challenge to connect everyone digitally, the organization has helped connect over 1,000,000 people to affordable internet offers, distributed over 6,000 devices, and trained thousands of people in digital skills. EveryoneOn is known for its Offer Locator Tool where people can search for low-cost internet service and computers in their area.

To reach more people, EveryoneOn partners across sectors with government, local and national nonprofits, corporations, and internet service providers to connect more people and build digital literacy. Partnerships with technology companies allow EveryoneOn to provide devices to program participants at low or no cost. They also partner with community-based organizations to deliver digital skills training. EveryoneOn primarily works in communities of color and provides services in Spanish and English (Figure 5.27).

In response to the pandemic, EveryoneOn developed a hybrid model in which clients got initial support for their new computers in person from EveryoneOn. They completed their classes online. By providing equipment, access and education, EveryoneOn narrowed the digital divide in many communities of color.

Although we still have work to do, the response of educators, businesses, nonprofits, and government is adding even more people to the digital superhighway. Although the digital divide is far from closed, the interconnected responses of people like you working together with social institutions makes a difference. Equal access is social justice.

5.5.3 Licenses and Attributions for Education and Transformation

Open Content, Original

“Education for Transformation is Social Justice” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 5.26. “Interdependent Solutions to Education during COVID-19” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Digital Divide” definition from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 5.22. “Photo” by novohorizonte de Economia Solidaria is in the Public Domain.

Figure 5.23. “bell hooks” by Kevin Andre Elliot is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Figure 5.24. “Open Oregon Educational Resources Logo” by Open Oregon Educational Resources is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 5.25. “% of US Adults Who Say They Have or Own the Following” from “Some digital divides persist between rural, urban and suburban America” © Pew Research Center, Washington, D.C. is licensed under the Center’s Terms of Use.

Figure 5.27. “Photo of students learning digital literacy skills at EveryoneOn, during the COVID-19 pandemic” © EveryoneOn is all rights reserved and used with permission.