8.2 Climate Change as a Social Problem

Patricia Halleran; Kimberly Puttman; and Avery Temple

Scientists believe global climate change is the greatest challenge humanity has ever faced. But what exactly is climate change? What causes climate change? Why is it a social problem and not just an environmental problem?

Climate change refers to the long-term shift in global and regional temperatures, humidity and rainfall patterns, and other atmospheric characteristics. Unlike changes in weather that occur on a local level that can be measured in hourly, daily, or weekly fluctuations, climate change refers to longer-term fluctuations (both regionally or globally) that take place over a time scale of seasons, years, or even decades.

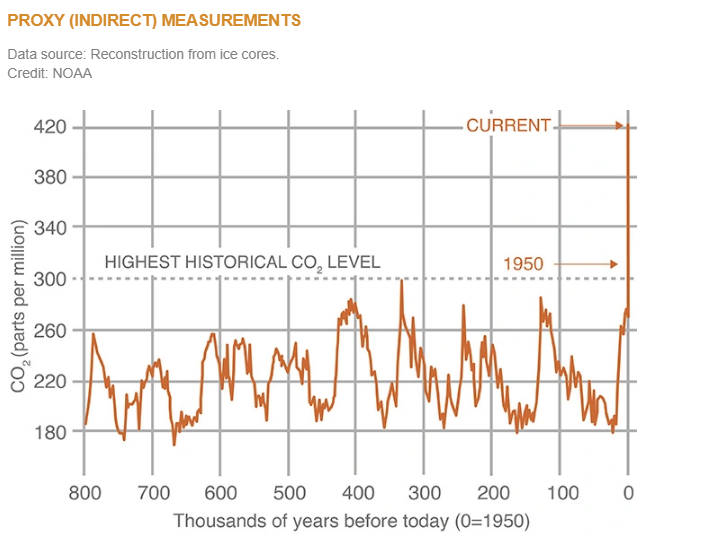

In the past two centuries, an exponential increase in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases have been released into the earth’s atmosphere, as the chart in Figure 8.3 shows. Although there are some natural processes that affect the earth’s climate, such as volcanic eruptions, the vast majority of scientists worldwide attribute the speed at which global warming has recently occurred to human activity, most notably the burning of fossil fuels. Scientists examine ocean sediments, ice cores, tree rings, and changes in glaciers to understand variations in Earth’s climate over time.

Figure 8.3. This graph shows the level of Carbon dioxide (CO2) over time. Although some fluctuation is normal, CO2 levels have never been as high as they are now. The change is predominantly caused by burning fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas. Image description.

The Industrial Revolution is one reason for the increased carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Since the Industrial Revolution, the concentration of greenhouse gasses is higher than at any other time in the past 800,000 years. This increase in greenhouse gasses is called the greenhouse effect––an imbalance between the energy entering and leaving the earth’s atmosphere, resulting in a rise in global temperature. Because certain gasses absorb energy, such as carbon dioxide and methane, they trap heat and prevent it from being released into space, causing a rise in global temperature. The burning of fossil fuels is not the only human activity contributing to the greenhouse effect. Other activities such as deforestation, urbanization, and unsustainable agricultural practices contribute to global climate change.

So, climate change is a social problem because humans are causing the problem and are differently impacted by the problem. If you remember the definition of a social problem from Chapter 1, a social problem is a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world. Early sociological definitions of social problems rarely included the phrase “our physical world.” Today, climate change itself drives the importance of adding this phrase.

Climate change is a critical issue, no matter how we approach it. Scientists are studying how to minimize its effects on people and the environment more broadly and, with any hope, successfully plan for the uncertain future. We must first examine the various ways climate change is already a threat to societies and communities worldwide.

8.2.1 Extreme Weather Events

As you watch the news, you may notice that extreme weather events occur regularly around the world. Many scientists argue that these events are caused or at least made worse by climate change. An extreme weather event is defined by the severity of its effects or any weather event uncommon for a particular location. Some examples of these types of severe and unusual events in the US include Hurricane Katrina in 2005, which killed over 1800 people and caused $125 billion in damage; Hurricane Sandy in 2012, the third-most destructive hurricane ever to hit the nation; and the 2020 and 2021 wildfires that engulfed the West Coast states due to severe and prolonged drought and heat waves.

One of the most serious concerns Indigenous communities and other residents had about the Jordan Cove Energy Project discussed at the beginning of this chapter was the risk of a highly explosive gas pipeline being placed in a region increasingly inundated by annual wildfires. One of the large fires that swept through southern Oregon in September 2020 was located just a few miles from the planned route of the proposed pipelines, proving that the communities’ fears were valid.

And, as mentioned by communities of both Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, climate change and mismanagement of forests will continue to create ripe conditions for unprecedented wildfires. In the Good Fire podcast, which you can listen to if you’d like, hosts Amy Cardinal Christianson and Matthew Kristoff, along with guest Frank Lake, discuss the landscape surrounding fire management:

Wildfire management has long been the domain of colonial governments. Despite a rich history of living with, managing, and using fire as a tool since time immemorial, Indigenous people were not permitted to practice cultural fire and their knowledge was largely ignored. As a result, total fire suppression became the prominent policy (Kristoff 2019).

The Indigenous knowledge that might have protected us against wildfires has been suppressed. It is another consequence of colonialism, the domination of a people or area by a foreign state or nation (Definition of Colonialism N.d.). The residential schools that we learned about in Chapter 5 were a tool of social control used by colonists. It’s important to remember that colonialism is not something that occurred in the past. It is a structure of inequality that reproduces itself, even today (Wolfe 2006).

8.2.2 Cultural Loss

Figure 8.4. Salmon returning to their spawning grounds near Port Hope, Ontario, Canada. In the chapter’s next section, we will discuss what makes up a culture. How might access to salmon shape a culture? How might a lack of access to salmon impact that same culture?

Many cultures around the world are intimately connected to their environment. Certain foods, medicine, dance, and art are unique to places with particular animals, plants, or climates. With drastic temperature changes, extreme disasters, and biodiversity loss among plants and animals, people cannot practice many customs. This contributes to significant cultural loss around the world.

For example, salmon are an important symbol and food source for the Indigenous people in the Pacific Northwest (Figure 8.4). The imagery of salmon in Indigenous art demonstrates a deep connection to natural surroundings. However, one effect of climate change is the warming of bodies of water worldwide. Like many fish, salmon require a specific temperature to spawn. As water temperatures increase, salmon cannot spawn as effectively or at all. This severely impacts species who eat salmon as a staple in their diet and the Indigenous peoples who practice traditional methods of harvesting, crafting with, and cooking salmon.

Climate change can create cultural change or inhibit cultural expression.

8.2.3 Climate Change and Poverty: “Those who contribute the least suffer the most”

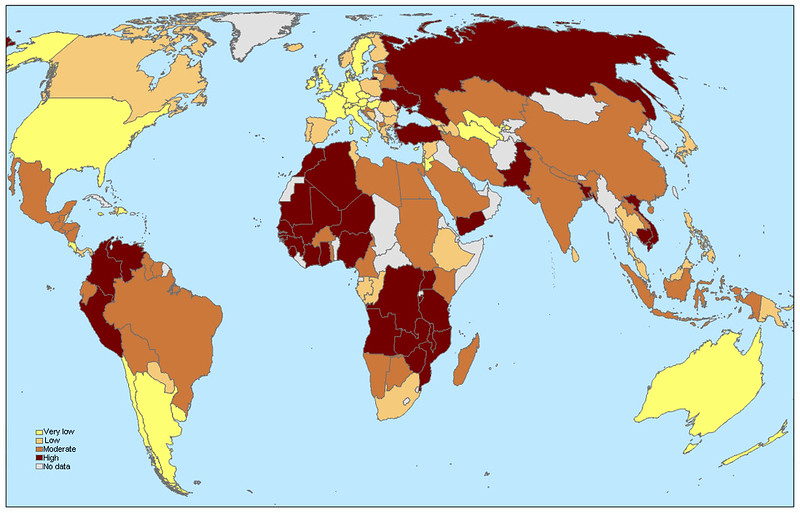

Figure 8.5. This map shows how vulnerable people in certain countries are to climate change. The United States, Australia, parts of Western Europe and the southern part of South America experience low vulnerability. Russia, most of Africa and Asia, and most of South America experience moderate or high vulnerability. How vulnerable to climate change is your community? Image description.

This index combines a country’s vulnerability to climate change, and its readiness to improve resilience. Much of Africa is both vulnerable and not ready. Most of North America is less vulnerable and more ready. However, looking at this data by country hides vulnerabilities that are unique to communities.

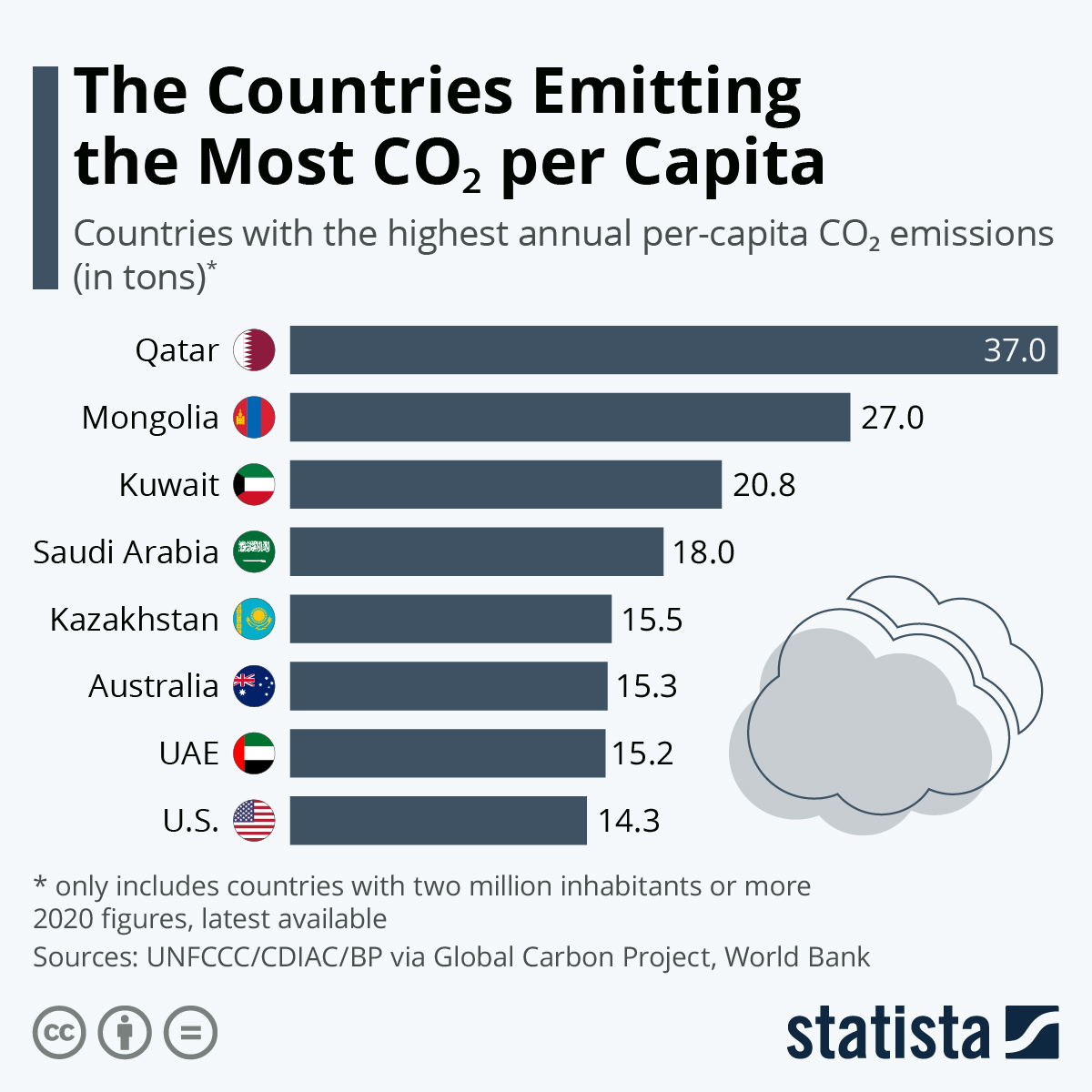

Figure 8.6. This graph shows countries with the highest annual per-capita CO2 emissions (in tons). How does it compare to the vulnerability to climate change in Figure 8.5? Image description.

This image shows emissions of carbon dioxide, an emission that contributes to global warming. A common saying in the environmental movement is, “Those who contribute the least suffer the most.” This means that the poorest people use the least planetary resources, so they contribute to climate change the least. However, they suffer the most from climate change. We can see this as we compare the maps in figures 8.5 and 8.6. We see, for example, that Africa contributes the least greenhouse gasses, but they are the most vulnerable to climate change. The United States is a high contributor of emissions but the least vulnerable to climate change. While this model doesn’t hold true for every country, the saying encapsulates a key issue with climate change.

We are experiencing more extreme weather events related to climate change. With Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans, those who contributed the least suffered the most. People with cars could evacuate. People without cars often couldn’t. People without cars contributed the least to CO2 emissions but experienced the most loss related to the extreme weather event (Bullard 2008).

You may have cheered with us as you learned that the Jordon Cove Energy Project pipeline project was shut down. However, the question remains: How else do we generate and transport our energy resources? Part of the answer is that the projects go where the resources exist, and the people are even more powerless to resist. Our unequal social locations contribute to inequality. To explore this further, we will look at the experience of people in Nigeria and oil production. We will build on the concept of socioeconomic class (SES) that we began in Chapter 6.

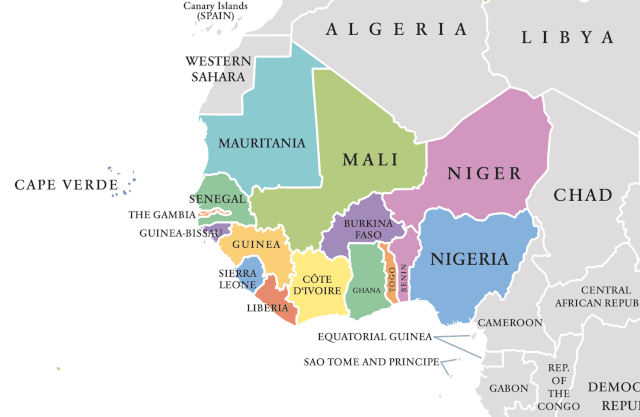

Figure 8.7. This map shows Nigeria, a country on the west coast of Africa. Nearly everyone there lives on less than $30.00 a day. Many people live on much less. How much do you think this country contributes to CO2 emissions? Image description.

Nigeria is a country on the west coast of Africa, as shown in Figure 8.7. More than 40% of the people in Nigeria live in extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $1.40 per day (Cuaresma 2018). Less than 15% of the people have access to clean fuel for cooking (Ritchie 2021), and less than 60% of the people have access to sufficient electricity (Ritchie and Rosado 2021). At the same time, Nigeria is one of the world’s top oil exporters. Oil companies use a practice called gas flaring, burning the waste gas from oil exploration rather than disposing of it in other ways.

Figure 8.8. This image shows a flame of gas burning in the background, and low quality houses and the people who live in them. Gas flaring causes poor health in Nigeria.

Poor Nigerians experience rashes and sores because of the toxic fumes. In a recent study, children exposed to flaring experience coughs, respiratory issues, fevers, and other poor health symptoms. The rate of child deaths in children under five also slightly increases (Alimi and Gibson 2022) The pollution contaminates the land, so women can’t grow enough food. Pollution also contaminates the water, leaving less for drinking and crop irrigation. One article notes that the women in the Niger Delta are poor because the environmental toxins are poisoning their plants. Women plant cassava to make their flour. However, the cassava roots are dying, and the women can’t replace them (Lawal 2021).

Many people are migrating to bigger cities, but it doesn’t solve the local pollution and emissions problem. The article, “In Nigeria, Gas Giants Get Rich as Women Sink Into Poverty” documents the story with more details, including pictures of the impacts of the gas flares, if you would like to learn more. We also notice that those who use the least resources are impacted the most. In this case, the environmental impact occurs on a different continent than most of the people using the oil. If you’d like to look more deeply into this problem, watch Who Is Responsible For Climate Change? – Who Needs To Fix It? .

8.2.4 Licenses and Attributions for Climate Change as a Social Problem

Open Content, Original

“Climate Change as a Social Problem” by Patricia Halleran, Kimberly Puttman, and Avery Temple is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.3. “Proxy (Indirect) Measurements” from “Carbon Dioxide” from NASA Global Climate Change/NOAA is in the Public Domain.

Figure 8.4. “Photo” by Brandon is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 8.5. “Unequal Vulnerability” by WorldFish is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.6. “The Countries Emitting the Most CO₂ Per Capita” by Katharina Buchholz, Statista is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0.

Figure 8.7. “West Africa map” by PirateShip6 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.8. “The impact of gas flaring on child health in Nigeria” by Ed Kashi, World Bank is included under fair use.