8.5 Environmental Justice Is Social Justice

Avery Temple and Kimberly Puttman

When we look at the problems of climate and environment, the sheer size of the issues can be disheartening. These issues are difficult to resolve because their causes and solutions are interdependent. For example, people in the US need oil to create gasoline for cars and fuel for industry. This voracious need encourages oil companies to produce oil efficiently. Industrial efficiency may incentivize some companies to use gas flaring in Nigeria. The causes of environmental degradation are linked in both obvious and subtle ways.

Solutions to environmental issues, particularly when they are effective, also reveal the power of our interdependence. Making a difference with this social problem requires both/and thinking, both individual agency and collective action. One optional video that explores how we can take action is We WILL Fix Climate Change [Video]. Let’s explore additional examples that look at collective action taken on regional, national, and international scales.

8.5.1 Environmental Justice in Oregon, Then and Now

The Bottle Bill

Figure 8.21. The Oregon Bottle Bill was the first law that created deposits for bottles. Do you think it has made a difference?

When I (Kim Puttman) was in college in the 1990s, I belonged to an organization known as OSPIRG, the Oregon Student Public Interest Research Group. During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the group was instrumental in environmental activism in the state. They advocated for laws and policies that would reduce consumer pollution. Their legacy includes the Oregon Bottle Bill. To learn more about it, watch the 1.41-minute video How Did We Get Here: Oregon’s Bottle Bill .

Then Oregon governor Tom McCall signed this bill, formally known as the Beverage Container Act of 1971, into law. With the support of other environmental groups and the legislature, the law became the first one in the nation to provide deposits on bottles and cans, encouraging people to return them rather than throw them away. The concept was both revolutionary and effective. In this post from the Oregon Historical Society, we see the consequences of this law, both then and now:

The Bottle Bill instantly reduced litter in Oregon. The share of beverage containers in roadside litter in the state declined from 40 percent before the law was passed to 10.8 percent in 1973 and 6 percent in 1979. The Bottle Bill also reinforces the practice of recycling. In the 2000s, about 84 percent of beverage containers were recycled, helping to make Oregon fourth in the nation for its rate of recycling (Henkles 2022).

In the case of action in one state, activists, beverage manufacturers and bottlers, grocery store owners and clerks, the legislature, and the governor all had to agree on what to do about the pollution problem. This new law had to be implemented and advertised through the media. For decades, grocery stores had to collect the initial refunds, process the bottles, and return the money to consumers. You may have even had a job that required you to handle these sometimes gross empty bottles.

From a relatively small beginning, the impact of this state law has grown. Multiple US states have enacted similar laws. The bottle bill has even grown in Oregon. The most recent iterations established bottle drops, a more efficient and hygienic way to process bottles and cans. Solving this kind of problem requires using our interconnectedness effectively, and the consequences continue rippling into the world.

The Latina Fire Survivors in Southern Oregon

Figure 8.22. Coalición Fortaleza grew from the experience of the Almeda Fire in southern Oregon. They value Unidad/Unity, Amor/Love, Dignidad/Dignity, Esperanza/Hope, Fuerza/Strength, Familia/Family, Justicia/Justice and Salud y Vida/Health and Life. With these values they are creating alternatives that support environmental justice. What values do you think are most important as we consider environmental justice?

Most Hispanic and Latino people say that global climate change is an important issue to address. Over 80% of them say that addressing climate change is of personal interest to them, a much higher percentage than the 67% of non-Hispanic people (Mora and Hugo Lopez 2021). Some of this focus may be because immigrants from Central America are migrating because of extreme climate events. It may also be that states with large percentages of Hispanic people like Texas, California, and Florida are experiencing more extreme weather events like drought, flooding, and wildfires.

In Oregon, where we experienced drought and unexpected wildfires in 2020, we see Latinos organizing for change. The Almeda fire in southern Oregon, impacted several communities which housed seasonal farm workers, mixed-status families, and low-income people. As a response, Latina and Indigenous women formed Coalición Fortaleza. It is a fire survivor organization which is creating options for survivors of the Almeda Fire in southern Oregon. They are working to re-home everyone. In doing so, they are strengthening their community and finding solutions that sustain Mother Earth. They write:

As experts of our own lived experiences, we have the imaginations, local knowledge and largest stake in ensuring that the rebuilding solutions don’t recreate the systems and conditions that have kept us in poverty and without access to life-saving information and resources. We will focus on community-led solutions that will serve our most impacted members. (Coalición Fortaleza 2023).

The group is committed to using the disruption of their community and its rebuilding to challenge the existing structures of power and create new, more equitable environmental justice.

8.5.2 Indigenous Resistance

Indigenous resistance to colonialism and climate destruction continues worldwide. Indigenous cultures are rooted in place, tradition, and land stewardship. Because there are Indigenous peoples on every acre of land that is habitable by humans, each act of destruction to the environment is also an act of destruction to the Indigenous peoples.

You may know that Indigenous people currently steward 80% of the world’s biodiversity (Raygoredetsky 2018). This is true because Indigenous peoples both resisted exploitation and created new systems for protecting the land, its inhabitants, and their cultures. These acts of resistance continue today. To learn more, watch Indigenous World View Can Preserve Our Existence [YouTube].

Figure 8.23. Water Protectors protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline in Standing Rock, North Dakota. Do you know anyone who went to Standing Rock?

A well-known example of Indigenous resistance in the United States is the land stewardship known as #noDAPL or Standing Rock. The picture in Figure 8.23 shows Indigenous Water Keepers protecting the water. The NoDAPL movement began when the Standing Rock Sioux people decided to fight the construction of a pipeline known as the Dakota Access Pipeline. This pipeline would be built on their ancestral land, destroying cultural resources and violating centuries-old treaties made between the tribe and the US government.

This led to intense protests where Indigenous peoples, allies, and community members from all over the world came to occupy and resist the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline. More than 300 people were injured, and hundreds were arrested during these protests by the US government (Montare 2018). While the Dakota Access Pipeline was built, the NoDAPL movement paved the way for many contemporary Indigenous resistance movements in North America, which you have the option to explore in #StopLine3.

Figure 8.24. Zapatista Movement. In 1998, Zapatista women in Amador Hernadez, Southern Mexico, demanded daily that the Mexican military leave the village’s communal landholdings.

Another historical example of Indigenous resistance is the Zapatista movement (Figure 8.24). In 1994, an Indigenous armed organization named the Zapatista Army of National Liberation (EZLN) declared war on the Mexican Government. They demanded, “work, land, housing, food, health, education, independence, liberty, democracy, justice and peace.”

This uprising began in Chiapas, Mexico, as an occupation of land and continues to this day. The Indigenous and some politically aligned non-Indigenous peoples still assert sovereignty over their economic, social, and cultural development. The Zapatista movement is a current example of how Indigenous communities can defend their lands, cultures, and each other. You can learn more about the Zapatista movement if you’d like.

8.5.3 Paris Climate Agreements

Our interdependence is also reflected at the other end of the scale of social change. In 2015, the United Nations brokered an international treaty known as the Paris Agreement. The goal of the agreement is to limit the emission of greenhouse gasses to prevent additional global warming. This worldwide agreement was signed by 196 parties when it initially became a treaty, with the United States later withdrawing from the agreement on July 1, 2017, due to a decision made by President Donald Trump.

The United Nations writes this about the Paris Agreement:

The Paris Agreement is a landmark in the multilateral climate change process because, for the first time, a binding agreement brings all nations into a common cause to undertake ambitious efforts to combat climate change and adapt to its effects (United Nations 2022).

The core components of the agreement are:

- Countries will enact limits on greenhouse gas emissions for their countries by 2020.

- Countries will also develop energy alternatives that reduce emissions.

- Countries that need help will receive financial, technological, and infrastructure assistance.

As you might expect, the implementation of this agreement is complicated. Some environmentalists argue that the agreement doesn’t move fast enough to create the needed changes. When measuring progress in the five years since the agreement, the American Association for the Advancement of Science reports mixed results. On one hand, the implementation of some of the limits is starting to slow the emissions of greenhouse gasses. On the other hand, the United Nations has very little money to enforce the agreements, and countries, such as the United States, can leave the agreement anytime. If you’d like to learn more about the Paris Agreement, watch the 1:40 minute video What is the Paris Agreement and How Does It Work?[Video]

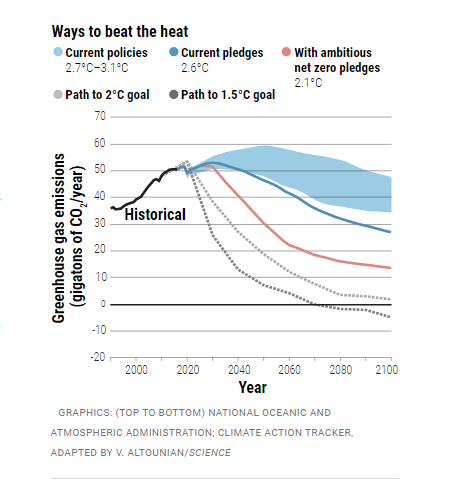

Figure 8.25. This chart shows the amount of greenhouse emission changes we would need to make in order to meet a variety of different scenarios related to limiting global warming. What action are you willing to take? Image description.

The chart in Figure 8.25 shows both the goal for emissions and our progress. If we stay with current policies shown in the blue-shaded area, the greenhouse gas emissions would result in an approximately 3 percent increase in global temperature. If we actually do the work specified in the Paris Agreement, temperatures would only rise by 2.6 degrees Celsius. Most climate scientists believe we need to do more to sustain life.

Even though progress is uncertain, the act of global solidarity is unprecedented. Global leaders are recognizing our shared interdependence. They are acting on a global scale to make a difference.

We live on one planet. All of our actions affect each other. Critical environmental justice tells us that those who create the least harm are often harmed the most. In order to heal our people and our planet, we strive for social justice. Laws like the bottle bill and the Paris Agreement, community re-building with Latina and Indigenous fire survivors and Indigenous led protests show us the way forward. How will you commit to environmental justice?

8.5.4 Licenses and Attributions for Environmental Justice is Social Justice

Open Content, Original

“Environmental Justice is Social Justice” by Avery Temple and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 8.21. “Photo” by Aleksandr Kadykov is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.22. “Artwork” © Erica Alexia Ledesma is all rights reserved and used with permission.

Figure 8.23. “Photo” from “Cities, Schools, and Government Officials” by NoDAPL Archive is included under fair use.

Figure 8.24. “In 1998, Zapatista women in Amador Hernadez demanded daily that the Mexican military leave the village communal landholdings” by Tim Russo from A Spark of Hope: The Ongoing Lessons of the Zapatista Revolution 25 Years On, Hilary Klein, North American Congress on Latin America is included under fair use.

Figure 8.25. “Greenhouse Gas emissions – goals, progress, and vision” from The Paris climate pact is 5 years old. Is it working? by Warren Cornwall, Science is included under fair use.