9.3 The Sociology of Social Movements

Nora Karena

Social movements are purposeful, organized groups that strive to work toward a common social goal. Movements can happen locally, at the state and national level, and worldwide. Let’s look at examples of social movements, from local to global. No doubt you can think of others on all of these levels, especially since modern technology has allowed us a near-constant stream of information about the quest for social change around the world.

9.3.1 Levels of Social Movements

Similar to the levels of society that sociologists study, as described in Chapter 3, social movements can occur at any level of society. This section describes the various levels. Local social movements typically refer to those in cities or towns but can also affect smaller constituencies, such as college campuses. Sometimes colleges are smaller hubs of a national movement, as seen during the Vietnam War protests or the Black Lives Matter protests. Other times, colleges are managing a more local issue.

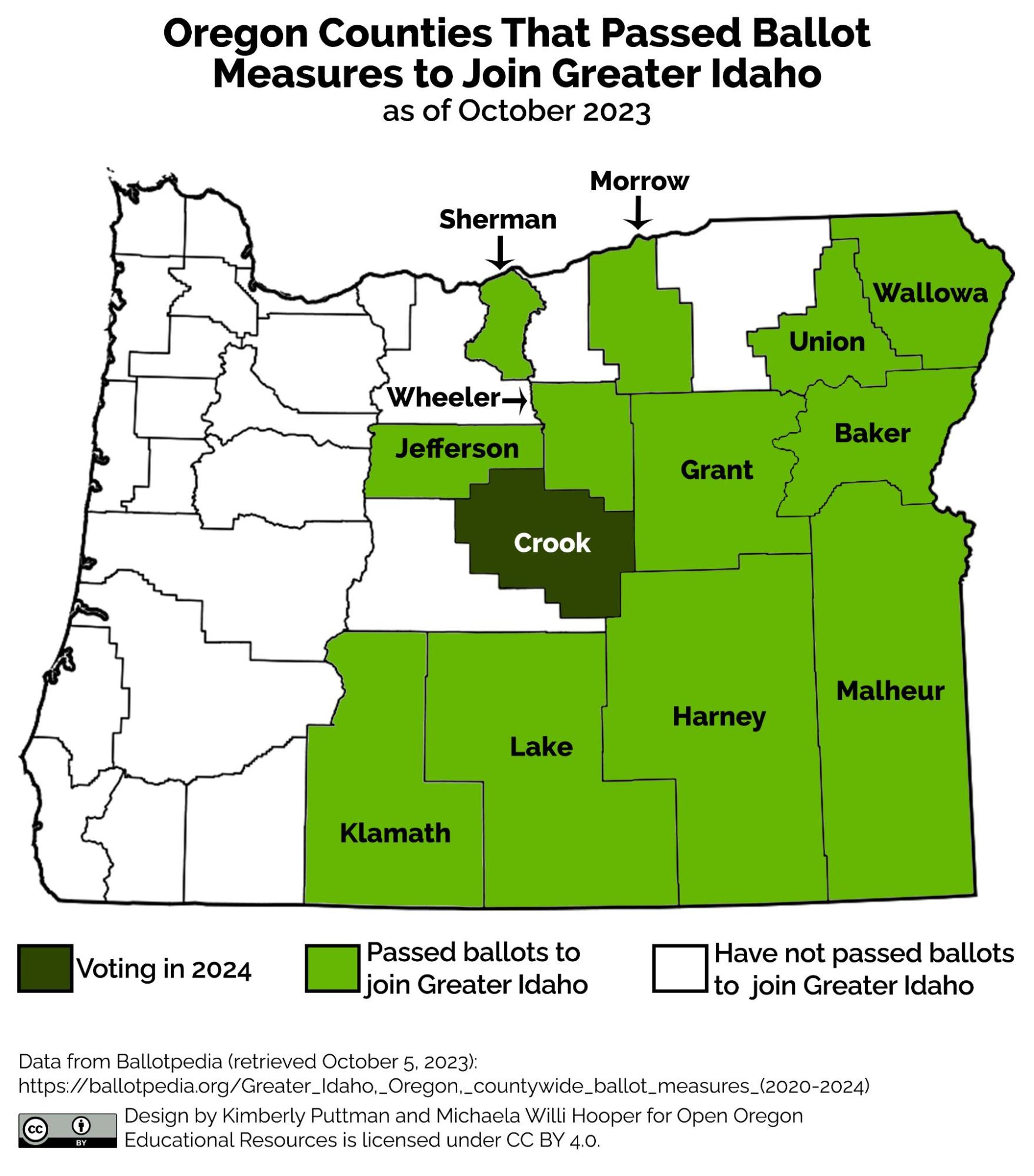

Figure 9.11. Some counties in Oregon want to become part of Idaho. This map shows how counties voted as of October 2023. The movement to join Greater Idaho is a state-level social movement. Do you know of any others? Image description.

The ultimate state-level protest would be to cease being a state. Organizations in several states are working toward that goal. In 2021, Harney County became the 11th county in Oregon to pass a non-binding ballot measure in support of moving the Idaho border to include large parts of rural Oregon, as shown in Figure 9.11. In 2022, Morrow and Wheeler counties voted similarly (Fixler 2022). Supporters of the initiative told reporters that they feel more aligned with Idaho’s conservative political culture and alienated from the liberal politics of the Portland metro area, where the majority of the state’s voters reside.

State-level organizing also shows up before and after national decisions. For example, the 2022 Supreme Court ruling that reversed Roe vs. Wade and ended the federally guaranteed right to get an abortion was met with a flurry of responses at the state level. Anti-abortion organizers had worked for years to prepare for this decision by putting in place trigger laws to immediately outlaw or severely restrict abortion access in the event of such a reversal. Other states responded with legislation to support access to abortion and other reproductive services. A notable and surprising response came from voters in Kansas, often considered reliably conservative and, by extension, anti-abortion. Kansas voters soundly rejected an attempt to repeal existing language in the state constitution that protects the right to abortion access. Each of these outcomes was shaped by competing social movements at the state level that either favor or oppose abortion access.

Many social movements worldwide mobilize collective action in response to global social problems such as poverty, inequality, and exploitation. Pro-democracy movements are also rising in response to perceived increases in authoritarianism and fascism. Some analysts cite the Arab Spring in 2010, Occupy in 2011, and Black Lives Matter protests worldwide to argue that we are in an age of global protests. In 2020, BLM protests took place in over 60 countries (Wikipedia N.d.), and blacklivesmatter.com includes significant information about and resources for global organizing for Black lives.

9.3.2 Types of Social Movements

Talking about Abolition…

Abolition is about presence—the presence of life-giving systems that allow people to thrive and be well, that prevent harm and better equip communities to address harm when it occurs.

-Ruth Wilson Gilmore

“Actually, the goal is not to have a world with no stealing, it’s to have a world with no hunger. That’s the abolitionists’ goal.” –

-Richie Reseda, Abolitionist, Producer, Organizer

We know that social movements can occur on the local, national, or even global stage. Are there other patterns or classifications that can help us understand them? One of the most common and important types of social movements is the reform movement, which seeks limited, though still significant, changes in some aspect of a nation’s political, economic, or social systems. It does not try to overthrow the existing government but rather works to improve conditions within the existing regime. Some of the most important social movements in US history have been reform movements, including many iterations of the women’s movement, which have addressed suffrage, economic discrimination, the labor movement, the civil rights movement, the Vietnam-era anti-war movement, movements for queer and trans liberation, and the environmental movement.

A report from the Pew Research Center found that about 55% of US adults expressed at least some support for Black Lives Matter in September 2020, and those numbers held steady in a 2021 follow-up poll (Menasche Horowitz 2021). However, a 2021 survey by the Oregon Values and Beliefs Center found that only 53% of adults in Oregon favored police reform measures. The same study also found that 27% of Oregonians favor abolishing the police altogether and funding social services and infrastructure for under-resourced and historically oppressed communities.

A revolutionary movement goes further than a reform movement in seeking to overthrow the existing government or institution and to bring about a new one and even a new way of life. Revolutionary movements have been common throughout history. Reform and revolutionary movements are often called political movements because the changes they seek are political.

The abolitionist ideals at the heart of BLM organizing principles can be considered revolutionary in that they challenge the very premise of policing as an effective or humane response to social problems. The Black Lives Matter website invites visitors to “join the movement for Freedom, Liberation and Justice. (Black Lives Matter 2023)” If you’d like to read their goals for yourself, please check out their website Black Lives Matter. Building on the work of social theorists like Angela Davis, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and Michelle Alexander, BLM organizers articulate an abolitionist vision that does not seek to reform policing but to replace the current criminal justice system with a system of transformative justice and community care. To learn more about what BLM organizers mean by “abolish the police,” you can watch the 3 part series, Imagining Abolition.

Another type of political movement is a reactionary movement, so named because it tries to block social change or to reverse already achieved social changes. #BlueLivesMatter emerged in 2016 as a powerful call to support and respect police and to defend the institution and traditions of police. Supporters assert that police officers are doing dangerous and misunderstood jobs that deserve respect. They claim that BLM organizing has made police work more dangerous and that the police have been victims of deliberate misinformation. This can be considered a reactionary movement as the goal is to block the social changes and maintain the status quo.

Two other types of movements are self-help movements and religious movements. As their name implies, self-help movements involve people trying to improve aspects of their personal lives; examples of self-help groups include Alcoholics Anonymous and Weight Watchers. Religious movements have elements of self-help and mutual aid. They generally aim to reinforce their members’ religious beliefs and convert other people to these beliefs. Principles from both religious and self-help movements have informed both reform and reaction movements.

9.3.3 Stages of Social Movements

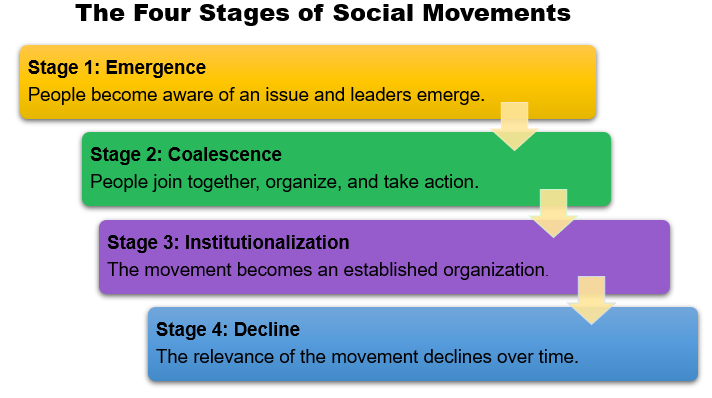

Figure 9.12. The Four Stages of Social Movements: Emergence, Coalescence, Institutionalization and Decline. Where do you think the movement inspired by #BlackLivesMatter is today in these stages? Image description

Sociologists also study the lifecycle of social movements—how they emerge, grow, and in some cases, die out. Blumer (1969) and Tilly (1978) outlined a four-stage process, shown in Figure 9.12. In the emergence stage, people become aware of an issue, and leaders emerge. This is followed by the coalescence stage, when people join together and organize in order to publicize the issue and raise awareness. In the institutionalization stage, the movement no longer requires grassroots volunteerism. The movement is now an established organization, typically with a paid staff. When people fall away and adopt a new movement, the movement successfully brings about the change it sought, or when people no longer take the issue seriously, the movement falls into the decline stage. In the next section, we will consider the role of social media in each of these stages.

9.3.4 New Social Movement Theory

Figure 9.13. Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells connects the power of the internet with the efficacy of social movements to explain their effectiveness in new ways.

New social movement theory, a development of European social scientists in the 1950s and 1960s, attempts to explain the proliferation of postindustrial and postmodern movements that are difficult to analyze using traditional social movement theories. Rather than being one specific theory, it is more of a perspective that revolves around understanding movements as they relate to class, politics, identity, culture, and social change. The Spanish sociologist Manuel Castells (Figure 9.13) looks at how technology is transforming social movements. He argues that because the internet allows communication between people, often outside a government’s control, social movements can be formed more rapidly and sometimes more effectively. He also believes that people act when their fear turns into anger about the oppression they experience and when they are motivated by hope. He writes:

…the second condition for individual experience to link up and form a movement is the existence of a communication process that propagates the events and the emotions attached to it. The faster and more interactive the process of communication is, the more likely the formation of a process of collective action becomes, rooted in outrage, propelled by enthusiasm and motivated by hope. (Castells 2015)

We see this combination of technology and passion present with #BlackLivesMatter-inspired organizing, and also with interrelated social movements for racial, gender, and disability justice, like ecofeminism, discussed inChapter 8, which focuses on patriarchal society as a source of environmental problems.

9.3.5 Resource Mobilization Theory

White American sociologists McCarthy and Zald (1977) proposed a new theory about social movements called resource mobilization theory. In resource mobilization theory, they say that social movements are successful when they can gather people and use their resources to create change. Resources include money, people, and power. The more money, people, and access to power a movement has, the greater its ability to make change. Resource mobilization can include funding secured from sympathetic allies and donors outside of the impacted community, which can give a movement increased visibility and influence.

9.3.6 Indigenous Perspective Theory

Figure 9.14. Sociologist Aldon Morris. He was the 112th president of the American Sociological Association. His work in social movements centers on the efficacy of Black organizing, which powered social movements.

Aldon Morris (Figure 9.14) researches the origins, nature, patterns, and outcomes of global movements that have successfully resisted and overthrown systems of oppression and injustice. With the Indigenous perspective theory, Morris argues it was the mobilization of the Black community’s internal resources, knowledge, power, and skill that powered both the 20th-century civil rights movement (CRM) and the 21st-century movement for Black lives (BLM). In both cases, specific systems of domination were identified by members of oppressed communities, who also planned and executed direct action and brought change. These community-based processes, which center on collective agency and lived expertise, become the foundation for a political base from which deliberate and effective collective action can emerge. To learn more about his work, please either watch the 2.18-minute video How Do People Make Change [Video] or read from Civil Rights to Black Lives Matter [website].

9.3.7 Licenses and Attributions for The Sociology of Social Movements

Open Content, Original

“The Sociology of Social Movements” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.11. “Oregon Counties that Passed Ballot Measures to Join Greater Idaho” by Michaela Willi Hooper and Kimberly Puttman, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Figure 9.12. “The Four Stages of Social Movements” by Kimberly Puttman, based on the work of Blumer and Tilly, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Levels, Types and Stages of Social Movements,” “New Social Movement Theory,” and “Resource Mobilization” and the definition of “Social Movements” are adapted from “Social Movements” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Lightly edited section content on levels, types, and stages of social movements and applied specifically to BLM and prison abolition movements.

Figure 9.13. “Photo of Manuel Castells” by Jorge Gonzalez is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

All Rights Reserved

Figure 9.14. Photo of Dr. Aldon Morris © Emile Pitre is all rights reserved and included with permission.