10.1 Chapter Overview and Learning Objectives

Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman

10.1.1 Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain how health is a social problem.

- Compare models of health that sociologists and health researchers use to explain inequality in health outcomes.

- Describe how sociologists make sense of health and illness over time.

- Evaluate the interdependent solutions for social justice equity in health outcomes, particularly during COVID-19.

10.1.2 Chapter Overview

My deepest gratitude goes to Kim Puttman, who helped guide me as I wrote this chapter during a tumultuous period of my life. She was a thoughtful tutor and mentor, and this chapter wouldn’t have been written without her.

-Kathryn Burrows

Figure 10.1 a and b. A) Isaiah – Voices of Long COVID [YouTube] and the first 5 minutes of B) Inside a long Covid clinic: ‘I look normal, but my body is breaking down’ [YouTube]. These two videos tell the story of people with long-haul COVID-19. As you watch, please consider how these experiences might create a social problem. 10.1 a Transcript. 10.1 b Transcript.

By now, we probably can all tell a story about how COVID-19, an infectious disease caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Coronavirus N.d.), has impacted our lives. Some of us have had family members or friends pass away. Some of us are still experiencing lingering symptoms from a COVID-19 infection, called long-haul or long COVID-19, as seen in Figure 10.1 a and 10.1 b. Some of our kids just felt achy or tired for a day and then got better. Some of us may not know anyone who was personally affected by COVID-19. Pause for a moment to think about your own COVID-19 health story and consider the many ways that this disease has affected society in the United States and worldwide.

My personal COVID-19 story has many layers. My wife and I quarantined, masked, and stayed socially distant for over two years. We isolated ourselves stringently because both of us have underlying health conditions which would make surviving COVID-19 difficult. My four parents followed these same protocols, missing visits with grandchildren, graduations, and family holidays. My dad had his 80th birthday party on Zoom, an event that we never could have predicted. My brothers and their families quarantined as requested early in the pandemic. They attended school from home, just as many governors ordered. One sister-in-law still went to the hospital to deliver babies and care for patients sick with COVID-19.

Luckily, no one in my close family had to be hospitalized for COVID-19, and no one passed away. People in my close family got sick, but everyone has recovered. Luck might have kept my family well, but equally important to consider is my social location. My family had safe, warm, comfortable housing where we could quarantine. We could order food and supplies online, and people would deliver them to our door. Many of us were able to complete our work remotely or at least adjust our work schedules. Although we had to wait until our age groups were eligible, our family had relatively easy access to vaccines. While these advantages don’t guarantee health, they gave us options to respond effectively during the pandemic.

This story highlights how health itself becomes a social problem, not just a medical one. Common sense tells us that since COVID-19 is a disease, it should affect all people equally. You would think that a virus wouldn’t discriminate.

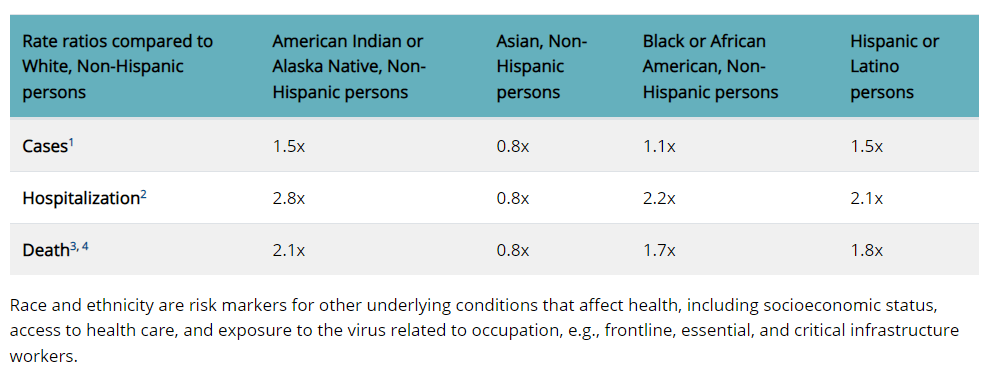

However, we have learned that some social groups are more likely to be infected, hospitalized, and even die as a result of contracting COVID-19. The table in Figure 10.2 shows rates of cases, hospitalizations, and deaths due to COVID-19 by race and ethnicity as of July 2020. As you can see, non-Hispanic Black people died from COVID-19 at a rate twice that of White people during this time. Please take a moment to look at the other differences related to race and ethnicity in this table.

Figure 10.2. Rates for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death by Race/Ethnicity, as of July 28, 2020. Race and ethnicity are risk markers for other underlying conditions that affect health, including socioeconomic status, access to health care, and exposure to related occupations, e.g. frontline, essential, and critical infrastructure workers. Image Description

Perhaps you noticed that the data show a gap between White non-Hispanic Americans and American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Black people, and Latinx people. As you can see in the table, cases, hospitalizations, and deaths for all racial and ethnic groups except for Asians are substantially higher than for Whites. This experience of inequality demonstrates that health and illness can be social problems.

This chapter will explore the social elements of health, a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity (World Health Organization 1946). We will look more deeply at why health is a social problem. We will explore collective and individual models of the social determinants of health. As we deepen our understanding of the social determinants of health, we will include the experience of individual and generational trauma as a factor in health outcomes. We will examine how sociologists make sense of health and illness by considering how these understandings develop over time. Like many other social problems, government policies and practices influence access to health resources and health outcomes. We will look at the differences in health systems internationally and decide if these systemic differences support health for everyone. Finally, we will come back to our own COVID-19 stories. The pandemic has both exposed and worsened existing inequalities. The pandemic is also inspiring creative action from individuals, communities, and governments. These generous responses demonstrate our interdependence, and the need for the social justice of health.

10.1.3 Focusing Questions

The questions that encourage our curiosity include:

- How is health a social problem?

- How do sociologists and health researchers model influences on health outcomes to measure health inequality?

- How do sociologists make sense of health and illness? How have our definitions changed over time?

- How has COVID-19 provided an opportunity to assess and create interdependent solutions that improve health outcomes to ensure social justice oppressed people?

Let’s learn about who gets well!

10.1.4 Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Overview and Learning Objectives

Open Content, Original

“Chapter Overview” by Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 10.2. “Risk for COVID-19 Infection, Hospitalization, and Death By Race/Ethnicity” by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved

Figure 10.1a. “Isaiah – Voices of Long COVID” by Resolve to Save Lives is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 10.1b. “Inside a Long Covid clinic: “I look normal, but my body is breaking down” by The Guardian is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

[/accordian]