10.3 Epidemiology in the US: Health Disparities by Social Location

Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman

Doctors and medical professionals focus most on the health of an individual. Sociologists and public health professionals focus on the health of groups. This specialty is called epidemiology, the study of disease and health and their causes and distributions. Epidemiology can focus on the differences between neighborhoods, states, or countries. As we look at health in the United States, we see a complex and often contradictory issue. On the one hand, as one of the wealthiest nations, the United States fares well in health comparisons with the rest of the world. However, the United States also lags behind almost every industrialized country in providing care to all its citizens. This gap between the shared value of health and unequal outcomes makes health and illness a social problem.

Sociologists and others who study human health have a detailed model that helps them make sense of health in groups. This model is called the social determinants of health. More specifically, the social determinants of health are the circumstances in which people are born, grow up, live, work, and age and the systems put in place to deal with illness (World Health Organization 2013). While ethnicity may seem to correlate with these elements, it is misleading to assume that all members of a specific racial group will experience the same health outcomes (Whitemarsh and Jones 2010). Instead, while certain diseases are linked to racial identity, lifestyle factors such as smoking and diet also play a role. These, of course, are also influenced by racial identity! These circumstances are shaped by a wider set of forces: economics, social policies, and politics.

10.3.1 Unpacking Oppression, Healing Justice: Social Determinants of Health and ACES

Sociologists and health researchers use two different models to predict health outcomes. Social determinants of health measure the social factors that may impact a community’s health outcomes. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) are potentially traumatic events that occur in childhood (0-17 years). The ACEs model measures the amount of trauma a child experiences and describes the impact of trauma on health outcomes. Trauma is a person’s (or group) response to a deeply distressing or disturbing event that overwhelms one’s ability to cope. Trauma causes feelings of helplessness, diminishes self-esteem and limits a person’s ability to feel a full range of emotions and experiences (Onderko 2018). Let’s examine both of these models.

Figure 10.6. This is a model of the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), provided by the CDC. How do these factors impact your own health or the health of your family? How might these factors impact the health of families who are different from you? Image Description

Social scientists and health professionals use this model of social determinants of health to describe the social factors that influence the health or lack of health of different social groups. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) created the model in Figure 10.6. We see that access to quality health care influences how healthy you might be. Whether your neighborhood is located next to an oil refinery, as described in Chapter 8, changes your health outcomes. You might be surprised that education access and quality also impact your health. However, you might remember from Chapter 5 that education and wealth are correlated. Wealthy people can pay more money for healthcare. Additionally, they get better educations, which sometimes leads to better health choices.

The way organizations and institutions create models for the social determinants of health can change what we see. If you’d like to explore this question more deeply, here is a model from the World Health Organization and a SDOH model from the Canadian First Nations Peoples. Why might these models be different from each other?

In a slightly different social model of health, researchers look at how trauma over time affects health outcomes.

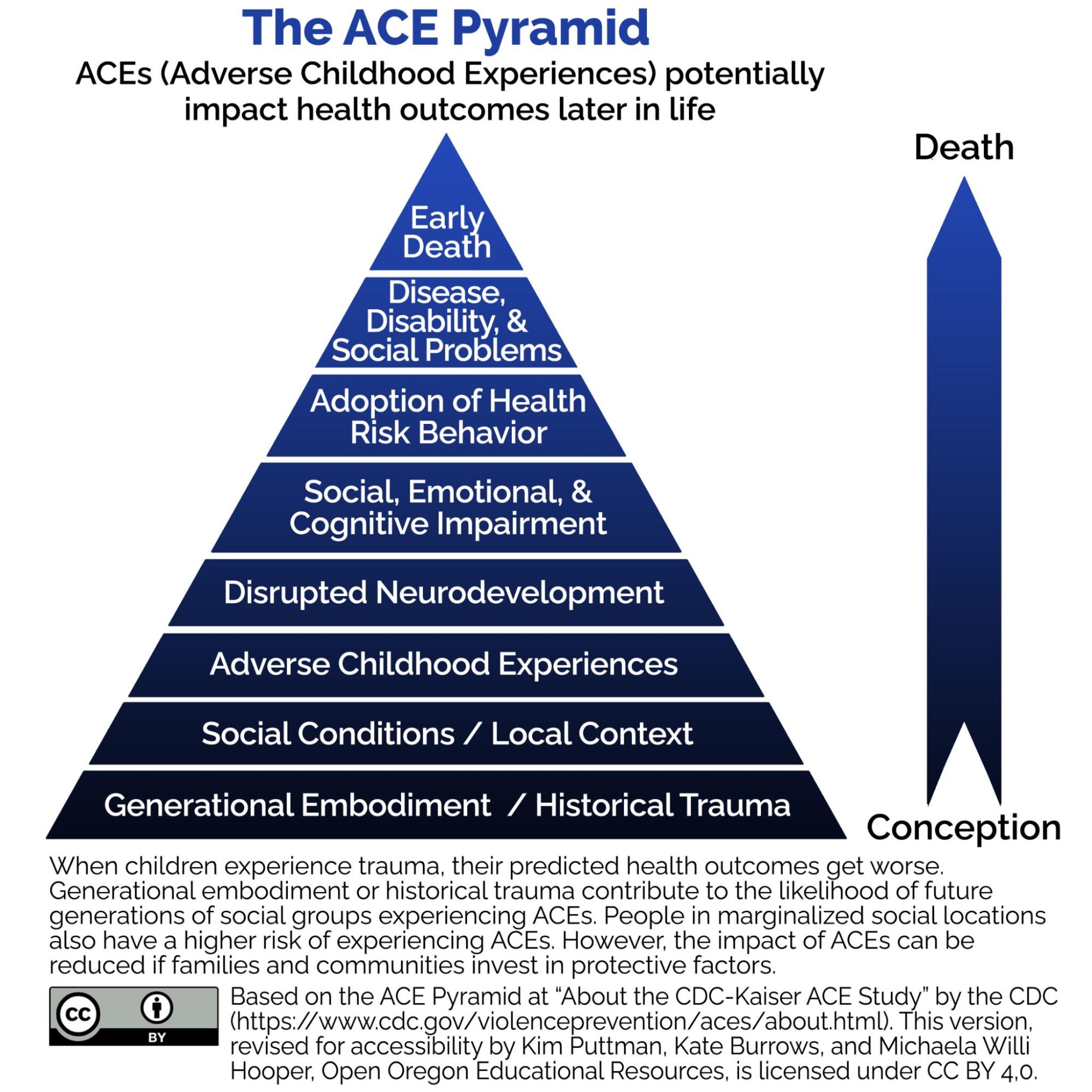

Figure 10.7. The ACE pyramid: Many of us experience some adverse childhood events. When communities and families invest in protective factors, the impact of ACEs on our future health outcomes decreases. Image description

Figure 10.7 shows the ACE Pyramid distributed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) potentially impact health outcomes later in life. An arrow on the side shows the progression from conception (at the bottom) to death (at the top). The levels, from conception to death, are:

- Generational Embodiment/Historical Trauma

- Social Conditions/Local Context

- Adverse Childhood Experiences

- Disrupted Neurodevelopment

- Social, Emotional, & Cognitive Impairment

- Adoption of Health Risk Behavior

- Disease, Disability, & Social Problems

- Early Death

When children experience trauma, their predicted health outcomes get worse. These adverse or traumatic experiences may include growing up in a family with mental health or substance abuse issues, child abuse, or other experiences of violence. Because a person who experiences these events is more likely to experience some physical and mental health challenges in childhood, they are more likely to adopt risky behaviors as an adult. Additionally, the more ACEs an adult has, the more it can predict that person’s risk of developing health problems such as diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. If left untreated, the related diseases and disabilities can lead to early death.

However, when children get help from caring adults, are connected with others, or receive competent professional support, they can recover from this early trauma. These interventions and others are known as protective factors. If families and communities support children with protective factors, the negative health impacts of trauma decrease. Many people experience at least one Adverse Childhood Experience in their lifetime. However, people in marginalized social locations have more risk of ACEs.

Beyond the experience of an individual, generational embodiment or historical trauma contributes to the likelihood of future generations of social groups experiencing ACEs. Historical trauma is multigenerational trauma experienced by a specific cultural, racial or ethnic group (Administration for Children and Families N.d.). It is related to major events that oppressed a particular group of people because of their status as oppressed, such as slavery, the Holocaust, forced migration, and the violent colonization of Indigenous people in North America. The generational embodiment of this trauma means that trauma responses of a previous generation are passed down to future generations unless they are healed. For a deeper look at how ACEs work, you have the option to watch this TED Talk, “How Childhood Trauma Affects Health Across a Lifetime.”

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and heal justice.

This particular activity has two options:

- Create a Social Determinants of Health model for your community. You’ll want to look at the two models presented here to understand what to illustrate. Then, you can research factors that influence your community’s health. You might have only a small hospital—so access to health services is low. You might have really clean ocean air, so environmental risk factors are low. How might you illustrate that one is low and one is high – perhaps the size of the shapes could change. Many counties have a county health assessment report like the one here: Lincoln County Community Health Assessment. A report or fact sheet like this for your area might be helpful.

- Improving health outcomes often starts with improving children’s lives. Please review this infographic from the Centers for Disease Control, We Can Prevent Childhood Adversity. What risk factors are most relevant in your community? How could you improve the protective factors for your children or children in your community?

10.3.2 Health Inequalities by Race and Ethnicity

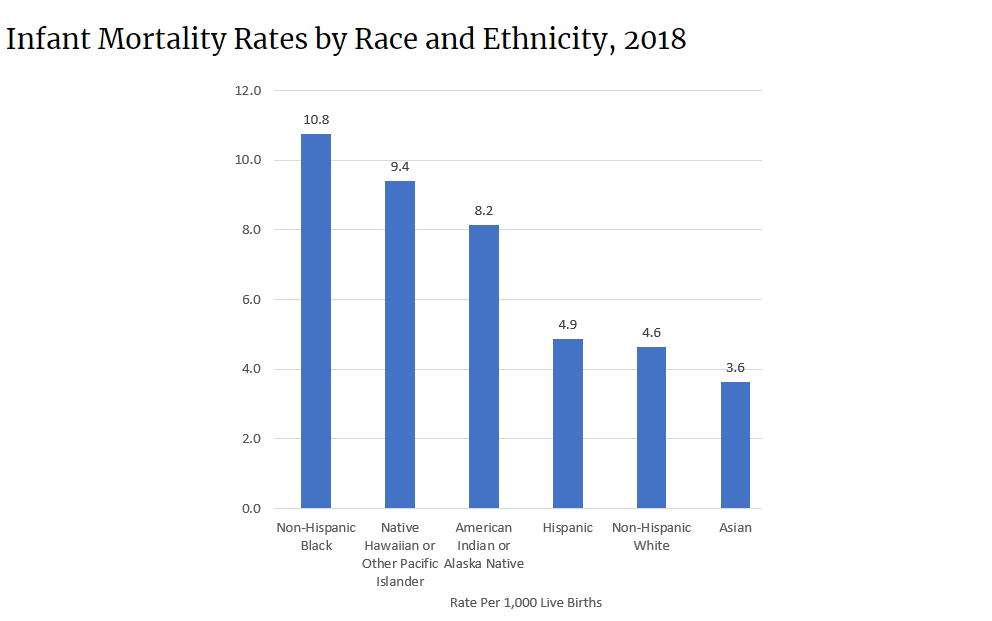

When looking at the social epidemiology of the United States, it is easy to see health disparities between people with different races and ethnicities. The discrepancy between Black and White Americans shows the gap clearly. In 2018, the average life expectancy for Black males was 74.7 years. The average life expectancy for White males was 78.5 years. This is a gap of almost 5 years (Wamsley 2021). Mortality measures how many people die at a particular time or place. Many families have experienced the tragedy of losing an infant, and it can be hard to talk about. We see similar disparities when we look at how many babies die or infant mortality. The 2018 infant mortality rates for different races and ethnicities are as follows:

Figure 10.8. Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity, 2018. Infant mortality varies significantly by race and ethnicity. How might applying the Social Determinants of Health model help us to understand why? Image Description

According to a report from the Kaiser Family Foundation (2007), African Americans also have a higher incidence of several diseases and causes of mortality, from cancer to heart disease to diabetes. Mexican Americans and Native Americans also have higher rates of these diseases and causes of mortality than White people.

Lisa Berkman (2009) notes that this gap started to narrow as a result of the Civil Rights movement in the 1960s but began widening again in the early 1980s. What accounts for these persistent disparities in health among different groups? Much of the answer lies in the level of healthcare that these groups have access to. The level of healthcare is measured by specific quality measures, standards that measure the performance of healthcare providers for patients and populations. For example, quality measures include how many people get a flu shot, how long someone has to wait to see a doctor, or how often medication given for low blood pressure actually results in lower blood pressure. Quality measures can identify important aspects of care like safety, effectiveness, timeliness, and fairness.

The National Healthcare Disparities Report used quality measures and social location to examine healthcare inequality. Even after adjusting for insurance differences, they found that Black, Indigenous, and People of Color receive poorer quality of care and less access to care than White dominant groups. The report identified these racial inequalities in care.

- Black people, Native Americans, and Alaska Natives receive worse care than Whites for about 40 percent of quality measures, which are standards for measuring the performance of healthcare providers to care for patients and populations.

- Hispanics, Native Hawai`ians, and Pacific Islanders receive worse care than White people for more than 30 percent of quality measures.

- Asian people received worse care than White people for nearly 30 percent of quality measures but better care for nearly 30 percent of quality measures (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality 2020).

Although there are multiple, complex reasons for discrepancies in care, a simple illustration may help make the point. Medical professionals and public health workers are asking why Black and Brown people are more likely to die of COVID-19. One medical study examined the pulse oximetry measurements of Black and White people in the hospital. If you’ve been to the hospital, you likely have had to put your finger into a little device that tells the medical professionals how much oxygen is in your blood. That’s oximetry. The study’s authors examined how often these measurements were accurate for White and Black patients.

They found that Black patients were three times more likely than White patients to have shortages of oxygen in the blood that the monitor didn’t pick up. Because COVID-19 mainly attacks the lungs and reduces oxygen, the discrepancies in the measurements of this device may lead to more medical complications in Black patients (Sjoding et al. 2021, Wallis 2021). In addition, blood oxygenation levels are part of complex automated medical alerts. If the measurements are wrong, they do not trigger the alerts which notify medical professionals to respond. Therefore, the related levels of care are lower and less effective for Black patients. To learn more, you have the option to watch the 4:47-minute video: Investigating Claims That Oximeters Give Inaccurate Readings To Patients With Darker Skin [Video].

10.3.3 Health Inequalities by Socioeconomic Status

The social location of wealth or poverty often influences health outcomes (Patel 2020). Marilyn Winkleby and her research associates (1992) state that “one of the strongest and most consistent predictors of a person’s morbidity [incidence of disease] and mortality [death] experience is that person’s socioeconomic status (SES). This finding persists across all diseases with few exceptions, continues throughout the entire lifespan, and extends across numerous risk factors for disease.” In other words, having a lower SES makes you more likely to get sick or die of disease than people with a higher SES.

In Ijeoma Oluo’s blog post, “Healthcare…can’t live with it….can’t live without it,” the author describes her childhood experience in Japan. Feel free to read it for yourself if you’d like to. She explores how being poor changes a current healthcare crisis for her mother and her own ability to eat without pain. She writes that when you are poor, the only option you have when a tooth goes bad is to get it pulled. Even if you get richer as an adult, your mouth tells the story of your poverty because it is full of gaps (Oluo 2022). Although this post contains some strong language, feel free to read it to learn more.

Money is only part of the SES picture. Social class also influences how likely you are to have health insurance. Particularly in the United States, where healthcare is not universal, the poorer you are, the less likely you are to have quality health insurance. Suppose you have a full-time, beneficial managerial job in a large multinational corporation. In that case, you will likely receive paid time off, excellent health insurance, long-term care insurance, and contributions to your retirement. This package of benefits helps you to prevent disease and stay healthy.

Conversely, suppose you have a low-wage seasonal job, particularly in a state that doesn’t participate in the Affordable Care Act. In that case, neither your employer nor the government provides health care insurance for you. You pay for your health care out of your own pocket. Given the high cost of care, you will likely delay getting treatment, not have access to preventative care, or not be able to pay for complex treatment. In the US, economics, insurance, and health outcomes are linked in enormously inequitable ways.

But economics isn’t the only driver of health outcomes. As we discussed in Chapter 6, class and education are related. Education is another variable that influences health outcomes. Phelan and Link (2003) note that many behavior-influenced diseases like lung cancer (from smoking), coronary artery disease (from poor eating and exercise habits), and HIV/AIDS initially were widespread across SES groups. However, once information linking habits to disease was shared, these diseases decreased in high SES groups and increased in low SES groups. This illustrates the important role of education initiatives regarding a given disease and possible inequalities in how those initiatives effectively reach different SES groups.

To find data on why people of low SES are more likely to contract and die from COVID-19, we look outside the United States to a study conducted in England. The study finds that people who are poor are more likely to live in overcrowded or substandard housing. These conditions make it challenging for the people who live there to quarantine effectively or maintain social distancing.

According to this study, people who are poor are more likely to be essential workers: servers, grocery clerks, delivery drivers, and other service workers. These essential workers have been required to keep their jobs and continue their interactions with many other people, increasing their risk of exposure to the virus. These essential workers are indeed heroes, but they had little choice because of their social location. If we wanted to recognize them, instead of just calling them “heroes,” we could raise wages.

Finally, because people with a lower socioeconomic status experience financial insecurity, they can be more stressed. This stress often translates into weakened immune systems, making it difficult to fight the virus. Finally, poorer people may delay going to the hospital because they have less access to quality healthcare. Because they have to wait until their health is in crisis to get medical attention, their symptoms are more severe, making it more difficult for them to recover.

10.3.4 Health Inequalities by Biological Sex

The Pandemic has finally opened our eyes to the fact that health is not driven just by biology, but by the social environment in which we all find ourselves and gender is a major part of that.

–Professor Sarah Hawkes, Co-Director of GH5050

In addition to race, ethnicity, and class, gender also influences health outcomes generally, and COVID-19 outcomes more specifically. During the pandemic, women are more likely to be caregivers for family members and work as frontline health workers than men, increasing their risk of exposure. If you’d like to learn more, A Gender Perspective on COVID-19 [YouTube], the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace, and Security highlights some of the ways females may experience COVID-19 differently than males.

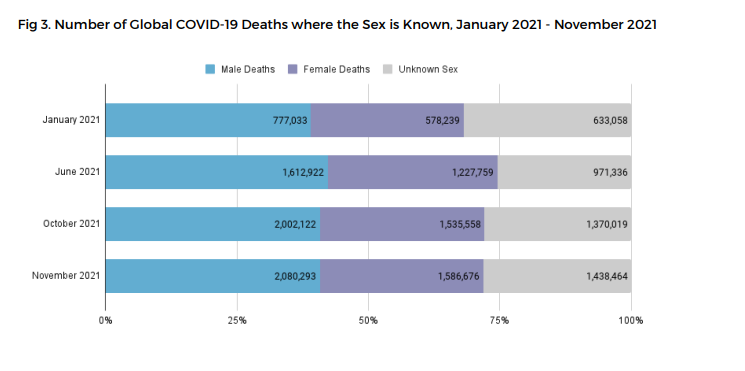

Over time, though, worldwide data is showing that women and men are getting infected with COVID-19 at near equal rates. Stereotypes regarding the types of occupations and tasks taken on by women that led them to get more serious COVID-19 infections did not hold up once the statistics started to come in. In fact, men are more likely to die from a COVID-19 infection than women.

Figure 10.9. Number of Global COVID-19 Deaths Where Sex is Known, as of 2021. Men die more frequently. Image description

The Sex, Gender, and COVID-19 Project works to collect all kinds of COVID-19 numbers, and dis-aggregate, or separate, the statistics by male, female, or non-binary gender. The chart in Figure 10.9 demonstrates that more men are dying from COVID-19 than women.

To understand why this is so, the social scientists from this project highlight both biological sex characteristics and socially constructed gender. They note that men have higher levels of an enzyme called ACE2. This enzyme allows viruses to enter cells more easily, which might tend to make men sicker than women. In addition to biological differences, the evidence highlights differences in behavior and social structures. In general, men tend to engage in more risky health behaviors such as drinking and smoking. These behaviors lead to poorer overall health and more risk of early death. Also, men tend to seek treatment later than women. The scientists write:

However, experience and evidence thus far tell us that both sex and gender are important drivers of risk and response to infection and disease. For example, even in the case of ACE2 (the enzyme that helps the virus enter the body’s cells), there are generally more ACE2 receptors in the heart cells of someone with pre-existing heart disease. And heart disease itself is associated with gender. In many societies today it is men who are more likely to suffer from heart disease and chronic lung disease as they are more frequently smokers, drinkers or working in occupations that expose them to risk of air pollution.

Other gender-based drivers of inequality may include men’s generally lower use of health services, including preventive health services – which might mean that men are further along in their illness before they seek care, for example. (The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project 2022)

We are reacting to the COVID-19 pandemic and trying to understand complex links between the causes of pandemic sickness and death at the same time, so our scientific conclusions may change as we learn more. Even if the final analysis changes, gender is one dimension of difference that helps to explain unequal health outcomes during COVID-19.

Gender is also a key variable in understanding health with a wider lens. Women are affected adversely both by unequal access to and institutionalized sexism in the healthcare industry. According to a report from KFF, women experienced a decline in their ability to see needed specialists between 2001 and 2008. In 2008, one-quarter of women questioned the quality of their healthcare (Ranji & Salganico 2011). Quality is partially indicated by access and cost. In 2018, roughly one in four (26 percent) women—compared to one in five (19 percent) men—reported delaying healthcare or letting conditions go untreated due to cost. Because of costs, approximately one in five women postponed preventive care, skipped a recommended test or treatment, or reduced their use of medication due to cost (Ranji, Rosenzweig, and Salganicoff 2018).

In addition, many critics also point to the medicalization of women’s issues as an example of institutionalized sexism. Medicalization refers to the process by which previously normal aspects of life are redefined as deviant and needing medical attention to remedy. Historically and contemporaneously, many aspects of women’s lives have been medicalized, including premenstrual syndrome, menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, and menopause. The medicalization of pregnancy and childbirth has been particularly contentious in recent decades, with many women opting against the medical process and choosing natural childbirth.

Fox and Worts (1999) find that all women experience pain and anxiety during the birth process but that social support relieves both as effectively as medical support. In other words, medical interventions are no more effective than social ones at helping with the difficulties of pain and childbirth. Fox and Worts further found that women with supportive partners had less medical intervention and fewer cases of postpartum depression. Of course, access to quality reproductive health support outside the standard medical models may not be readily available to women of all social classes. It is also important to note that not all people with a uterus who may need this kind of healthcare identify as female and may face additional burdens finding reproductive healthcare.

Reproductive health is not limited to pregnancy and childbirth. It also includes the ability to choose when or whether to be pregnant. For centuries, women have controlled conception and pregnancy using plants and devices. As women’s bodies became more medicalized, contraception and termination of pregnancy became managed by doctors. In some cases, this was useful. Doctors developed “the Pill” in the 1950s. It was widely available in the 1970s (Liao and Dolin 2012). By reliably preventing conception, women had more choices in when to get pregnant. Often, this gave them more freedom to work, make money, and gain economic power.

The technology to provide safe, effective terminations of pregnancy also evolved. Abortion is the spontaneous or voluntary termination of pregnancy. As women fought to control their reproduction, the right to choose abortion became a hotly contested debate.

Figure 10.10 a and b. Activists supporting Roe V Wade, then and now. Why might reproductive rights be expanded and then removed?

On January 22, 1973, the Supreme Court affirmed the right to a woman’s privacy in matters surrounding her pregnancy in a 7-2 decision, commonly known as Roe v. Wade. The decision reads in part:

The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment protects against state action the right to privacy, and a woman’s right to choose to have an abortion falls within that right to privacy. A state law that broadly prohibits abortion without respect to the stage of pregnancy or other interests violates that right. Although the state has legitimate interests in protecting the health of pregnant women and the “potentiality of human life,” the relative weight of each of these interests varies over the course of pregnancy, and the law must account for this variability (Oyez N.d.).

Since then, women have had access to abortion services in all US states. With access to safe and effective abortion, women’s health outcomes improved. Maternal mortality decreased, and there was less infant mortality (World Health Organization 2021).

However, like many social problems, some people did not agree that this law was correct. The conflict in values is based on politics, religion, and power. If you look at the conflict based on political party, you see that the Republican party argues that the unborn child has a right to life that cannot be violated. The Democratic party argues that people have the right to choose whether to get pregnant or to terminate pregnancy and to have access to safe, legal, affordable contraception and abortion.

However, not all Republicans and Democrats support their own party’s platform. Republicans who do support the platform are likely to be Protestant. 40% of them are White evangelical Christians (Lipka 2022). Republicans who don’t support the right to life are much less likely to be religious. 80% percent of Democrats support the right to life. The 20% who don’t are commonly White evangelical, Hispanic Catholic, or Black Protestant. The combination of race and religion appears to have a unique influence on beliefs about reproductive rights (Lipka 2022).

But differences in politics and religion mask a deeper divide: the debate over who controls women’s bodies. Generally, men make the laws that control women and pregnant people’s bodies. We’ll examine why this is in Chapter 12, when we discuss patriarchy.

We see the power of patriarchal systems in the challenges to Roe v. Wade. On June 24, 2022, access to abortion was removed as a federally protected right. Each state could decide whether abortions were legal or illegal. Many states limited the right to abortion. Other states protected the right to abortion.

The Supreme Court’s decision to have states decide abortion rights has worsened health outcomes for women, particularly if they are poor or women of color. Women and people with uteruses may be arrested in some states if they have abortions. Doctors may face legal charges if they take action to terminate pregnancies, even when it is to save the mother’s life. In mid-October 2022, a doctor was concerned about legal action in one case where the fetus would not survive at birth. The woman endured “a roughly six-hour ambulance ride to end her pregnancy in North Carolina, where she arrived with dangerously high blood pressure and signs of kidney failure” (Kusisto 2022). Because poor women and women of color, who are disproportionately poor, can’t afford to travel to states which protect abortion rights, they are even more at risk.

The medicalization of health, particularly regarding reproduction, encourages women and pregnant people to work for reproductive justice, a framework that centers on the human right to have children, not have children, and parent the children we have in safe and healthy environments (Beaumonis and Bond-Theriault 2017). If you want to learn more about reproductive justice, watch the 1.52-minute video: What is Reproductive Justice? [Video]

10.3.5 Health Inequalities by Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity

Gender identity and sexual orientation may also impact how a person experiences health and illness. However, understanding these unequal experiences based on sociological data is challenging. Because it has been illegal to be queer or transgender until recently in the United States, many people do not disclose their unique identities. The agencies that collect data about gender identity and sexual orientation have only recently begun to re-tool their data collection methods so that people can report their gender identity or sexual orientation. Despite these limitations, though, we notice inequality.

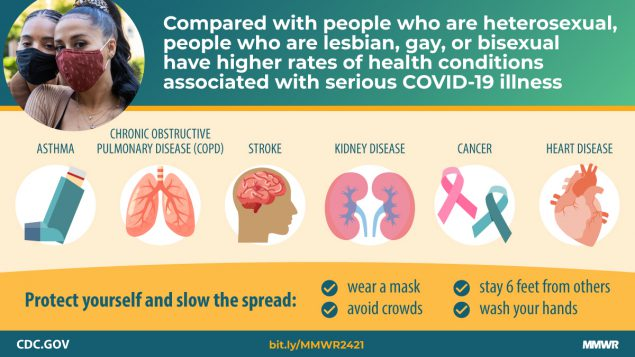

For example, when the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) examined risk factors for COVID-19 illness or death, they found that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people had challenging underlying health conditions more often than straight people (Figure 10.11). The report points primarily to economic causes as a core cause of the difference, indicating that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people, particularly if they are Black or Brown, experience less economic stability (Heslin and Hall 2021).

Figure 10.11. CDC Infographic COVID and LGBTQIA+ health (Heslin & Hall 2021). Because LGBTQIA+ people tend to be poorer than straight, CIS people, they often have more underlying conditions. These underlying conditions may put them at higher risk for poor COVID-19 outcomes. Image Description

When examining the overall health of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, the American College of Physicians finds similar issues. They also highlight the connections between laws, discrimination, and rejection that result in poorer health outcomes for LGBTQIA+ people:

These laws and policies, along with others that reinforce marginalization, discrimination, social stigma, or rejection of LGBT persons by their families or communities or that simply keep LGBT persons from accessing health care, have been associated with increased rates of anxiety, suicide, and substance or alcohol abuse (Daniel and Butkus 2015).

Transgender people have unique health concerns that are rarely addressed well by current practices. Although transgender people differ in their desires regarding medical support for their physical transitions, many of the procedures are not covered by insurance. When examining health outcomes for transgender people, the report states:

Transgender persons are also at a higher lifetime risk for suicide attempt and show higher incidence of social stressors, such as violence, discrimination, or childhood abuse, than nontransgender persons. A 2011 survey of transgender or gender-nonconforming persons found that 41 [percent] reported having attempted suicide, with the highest rates among those who faced job loss, harassment, poverty, and physical or sexual assault (Daniel and Butkus 2015).

In this episode of All Things Considered: Health Care System Fails Many Transgender Americans , which you can watch and read if you choose, the journalist notes that simple things, like having forms that indicate only male and female, become barriers to accessing health care services. Transgender people are more likely to experience preventable health conditions because it is difficult to find medical providers who will treat them with respect. The videos that are linked to this episode explore issues related to transgender health in more detail.

Figure 10.12. “So, you want to transition?” is student created artwork. They illustrate that the doctor holds a binary understanding of gender identity. The person looking to transition, meanwhile, is trapped by those options because their gender identity is nonbinary.

In our classroom piloting of this textbook, one student who participated in the open pedagogy of the Social Problems class and the Social Change class expanded our collective understandings of gender identity and sexual orientation. They shared their own experiences of gender identity and created art to convey the prejudice that they experience from the medical community. The image in Figure 10.12 conveys the understanding of the physician that gender can only be experienced in a binary way and the limited belief that transitioning means to fulfill one of those gender identities. When you examine the picture from the perspective of the trans person, you see both a key and a chain. The chain represents how a trans person is often chained to the binary during medical transition. The key represents how a trans-non-binary person would want to break away from the binary the medical system puts on them in order to meet the transition goals they actually have.

The student writes:

Being able to be a part of progress for the future and being able to influence the learning of people like me who take Sociology was an unexpectedly heart-warming experience. During the class itself, it didn’t feel that impactful. However, as the class was coming to a close, I got the sense that my, and the rest of my class, were going to change the class just as much as the class changed us.

I also got the opportunity. After noticing a gap in knowledge in the textbook about medical discrimination for trans people, I wrote an essay detailing the issues that trans people like myself deal with while trying to transition. While it was relevant then, it seems even more relevant now. When asked to elaborate artistically, as a nonbinary person myself, I was able to delve more into the feelings associated with such discrimination – frustration, helplessness, anger and shame. After sharing this essay and the art pieces illustrating my points, I felt that my efforts were actually going to do something beyond fulfilling the necessities of the assignment.

This experience in open pedagogy supported the student in telling their truth. Their classmates were able to learn from this example. One student even changed the topic of her paper from women’s reproductive rights to people’s reproductive rights, to honor the fact that not all people with uteruses identify as women. And, because this art and essay can be incorporated into the course build and textbook, future students are able to benefit.

Perhaps this doesn’t need to be said, but it is not the gender identity or sexual orientation per se that causes poorer health outcomes. Instead, it is the social structure embedded with stigma, discrimination, and violence that makes life riskier and shorter for LGBTQIA+ people.

10.3.6 Licenses and Attributions for Epidemiology in the US: Health Disparities by Social Location

Open Content, Original

“Epidemiology in the US: Health Disparities by Social Location ” by Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.7. “The ACE Pyramid” by Kimberly Puttman, Kathryn Burrows, and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Based on the ACE Pyramid in “About the CDC-Kaiser ACE Study” by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), which is in the Public Domain.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Health Inequalities by Biological Sex” is adapted from “Abortion, Pregnancy, and Childbirth” by Heidi Esbensen and Jane Forbes, Sociology of Gender: An Equity Lens [manuscript in press], Open Oregon Educational Resources, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Remixed.

“Health by Race and Ethnicity,” “Health By SES,” and “Health by Gender” are adapted from “Health in the United States” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Added additional details related to infant mortality rates, racism, COVID-19 and outcomes for LGBTQIA+ populations.

“Morbidity” definition from Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.6. “Social Determinants of Health Model” by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 10.8. “Infant Mortality by Race and Ethnicity, 2018” by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is in the Public Domain.

Figure 10.9. “Number of Global COVID-19 Deaths Where Sex is Known, as of 2021” by The Sex, Gender and COVID-19 Project is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Figure 10.10a. “Sen. Judiciary subcomm. Hearing on abortion amendment 1974” by Warren K. Leffler has no known copyright restrictions. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Figure 10.10b. “Roe v. Wade” by Susan Ruggles is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.11. “Infographic on Sexual Orientation and COVID-19” from “Sexual Orientation Disparities in Risk Factors for Adverse COVID-19–Related Outcomes, by Race/Ethnicity — Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, United States, 2017–2019” by the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.12. Artwork “So, you want to transition?” © EME, Student Soc 205 and 206 is all rights reserved and included with permission.