10.5 Health Equity is Social Justice

Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman

As we examine the social structures of health and healthcare in the US and worldwide, we see that governments influence health outcomes. In this policymaking step of the social problems process, governments decide who gets insurance, how people have access to clean water, or whether to fund initiatives related to reproductive health. We’ll see that laws, policies, and practices related to health care and health access affect the social problem of health.

10.5.1 Changing US Healthcare Policy

US healthcare coverage can broadly be divided into two main categories: public healthcare, which is funded by the government, and private healthcare, which a person buys from a private insurance company. The two main publicly funded healthcare programs are Medicare, which provides health services to people over sixty-five years old and people who meet other standards for disability, and Medicaid, which provides services to people with very low incomes who meet other eligibility requirements. Other government-funded programs include The Indian Health Service, which serves Native Americans; the Veterans Health Administration, which serves veterans; and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which serves children.

Private insurance is typically categorized as either employment-based insurance or direct-purchase insurance. Employment-based insurance is health plan coverage provided in whole or in part by an employer or union. It covers just the employee or the employee and their family. Direct purchase insurance is coverage that an individual buys directly from a private company.

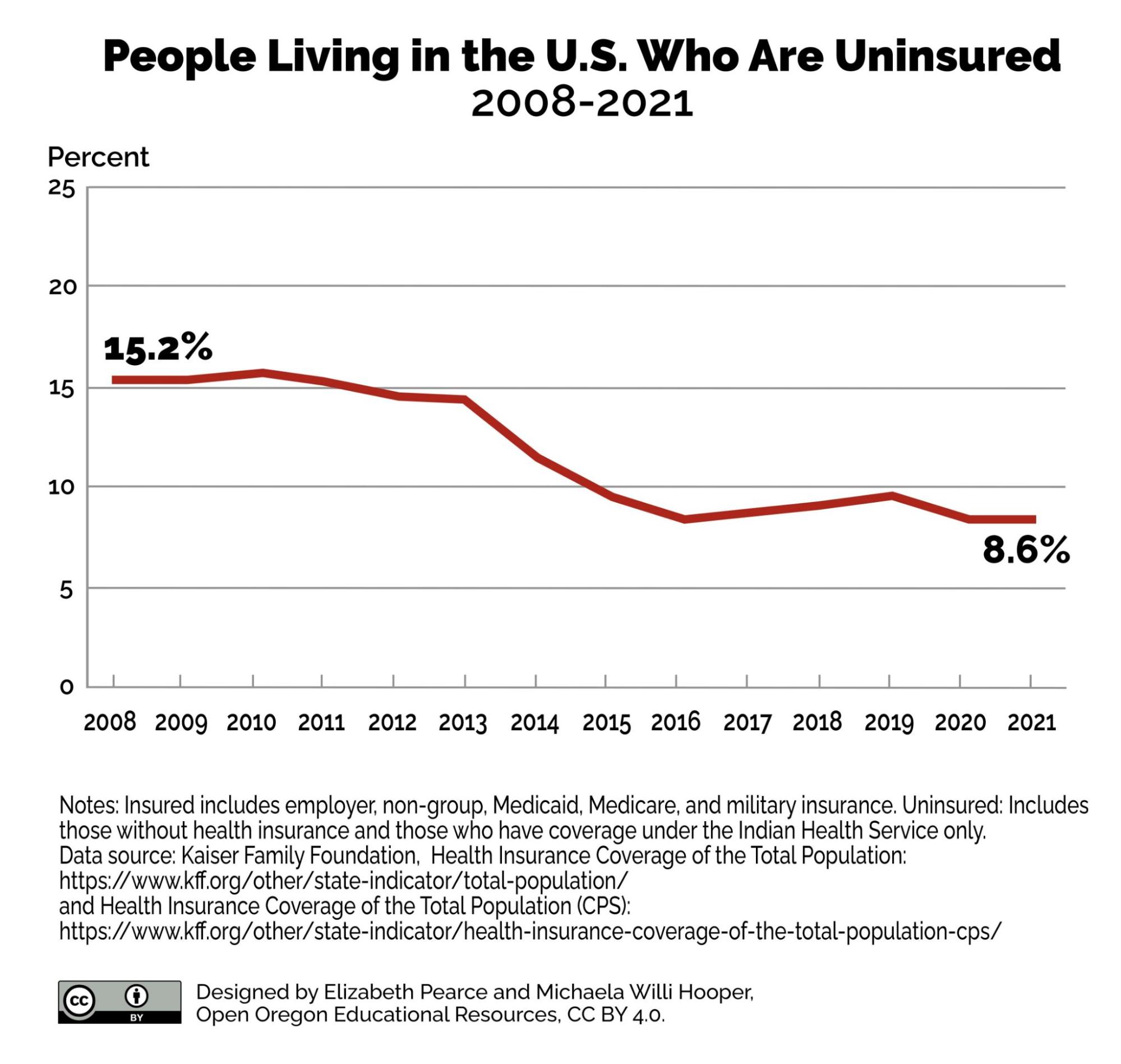

Figure 10.16. With the Affordable Healthcare Act, the percent of uninsured people dropped by nearly half. How do you think this could change healthcare costs and healthcare outcomes in the United States? Image description

The number of uninsured people is far lower now than in previous decades, but that doesn’t mean everyone has the healthcare they need. In 2013, and in many years preceding it, the number of uninsured people was in the 40 million range, or roughly 18 percent of the population. The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), which was implemented in 2014, allowed more people to get affordable insurance (Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act – Glossary N.d.).

Figure 10.17. The Affordable Care Act has been a savior for some and a target for others. As Congress and various state governments sought to have it overturned with laws or to have it diminished by the courts, supporters took to the streets to express its importance to them.

The Affordable Care Act (ACA) was a landmark change in US healthcare. Passed in 2010 and fully implemented in 2014, it increased eligibility to programs like Medicaid, helped guarantee insurance coverage for people with pre-existing conditions, and established regulations to ensure insurance premiums collected by insurers and care providers went directly to medical care (as opposed to administrative costs). It also included an individual mandate, which required anyone filing for a tax return to either acquire insurance coverage by 2014 or pay a penalty of several hundred dollars. Other provisions, including government subsidies, are intended to make insurance coverage more affordable, reducing the number of underinsured or uninsured people.

The ACA remained contentious for several years. The Supreme Court ruled in the case of National Federation of Independent Businesses v. Sebelius in 2012, that states cannot be forced to participate in the ACA’s Medicaid expansion. This ruling opened the door to further challenges to the ACA in Congress and the Federal courts, some state governments, conservative groups, and private businesses. The ACA has been a driving factor in elections and public opinion. In 2010 and 2014, the election of many Republicans to Congress came out of concerns about the ACA.

The uninsured number reached its lowest point in 2016, before beginning to climb again (Garfield, Orgera, and Damico 2019). People having some insurance may mask the fact that they could be underinsured; that is, people who pay at least 10 percent of their income on healthcare costs not covered by insurance or, for low-income adults, those whose medical expenses or deductibles are at least five percent of their income (Schoen et al. 2011).

However, once millions of previously uninsured people received coverage through the law, public sentiment and elections shifted dramatically. Healthcare was the top issue for voters going into the 2020 election cycle. The desire to preserve the law led to Democratic gains in the election (just a short time before COVID-19 began to spread globally). With its passage, response, subsequent changes, and new policies, the ACA demonstrates the interplay between policymaking, social problems work, and policy outcomes, the last steps of Best’s claimsmaking process.

Even with all these options, a sizable portion of the US population remains uninsured. In 2019, about 26 million people, or eight percent of US residents, had no health insurance. That number increased to 31 million in 2020 (Keith 2020). People don’t have health insurance for many reasons. Many small businesses can’t afford to provide insurance to their employees. Many employees are part time, so they don’t qualify for insurance benefits from their employers. Some people only have health insurance for part of a year (Keisler-Starkey and Bunch 2020). In addition, all states except for California and recently Oregon make it illegal for undocumented immigrants to receive Medicaid services through the ACA. Other states, such as Texas, are pushing to stop the spread of Medicaid to low-income citizens.

10.5.2 Changing Healthcare Policy Around the World

Clearly, healthcare in the United States has some areas for improvement. But how does it compare to healthcare in other countries? Many people in the United States believe that this country has the best healthcare in the world. While it is true that the United States has a higher quality of care available than many nations in the Global South, it is not necessarily the best in the world. In a report on how US healthcare compares to that of other countries, researchers found that the United States does “relatively well in some areas—such as cancer care—and less well in others—such as mortality from conditions amenable to prevention and treatment” (Docteur and Berenson 2009). This conflict between values and outcomes is another example of the conditions of a social problem: that values and outcomes do not match.

Some consider the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA) to be a slippery slope that could lead to socialized medicine, a term that for many people in the United States has negative connotations lingering from the Cold War era and earlier. Under a socialized medicine system, all medical facilities and expenses are covered through a public insurance plan that is administered by the federal government. It employs doctors, nurses, and other staff and owns and runs the hospitals (Klein 2009). The best example of socialized medicine is in Great Britain, where the National Health System (NHS) covers the cost of healthcare for all residents. Despite some US citizens’ reaction to policy changes that hint at socialism, the United States Veterans Health Administration (VA) is administered in a similar way to socialized medicine in other countries.

It is important to distinguish between socialized medicine, in which the government owns the healthcare system, and universal healthcare, which is simply a system that guarantees healthcare coverage for everyone. Germany, Singapore, and Canada all have universal healthcare. People often look to Canada’s universal healthcare system, Medicare, as a model for the system. In Canada, healthcare is publicly funded and administered by separate provincial and territorial governments.

However, the care itself comes from private providers. This is the main difference between universal healthcare and socialized medicine. The Canada Health Act of 1970 required that all health insurance plans must be “available to all eligible Canadian residents, comprehensive in coverage, accessible, portable among provinces, and publicly administered” (Kaiser Family Foundation 2010).

10.5.3 Reproductive Justice is Social Justice

Access to health insurance is not the only urgent social problem related to health. Issues related to reproduction and pregnancy are also social problems of health.

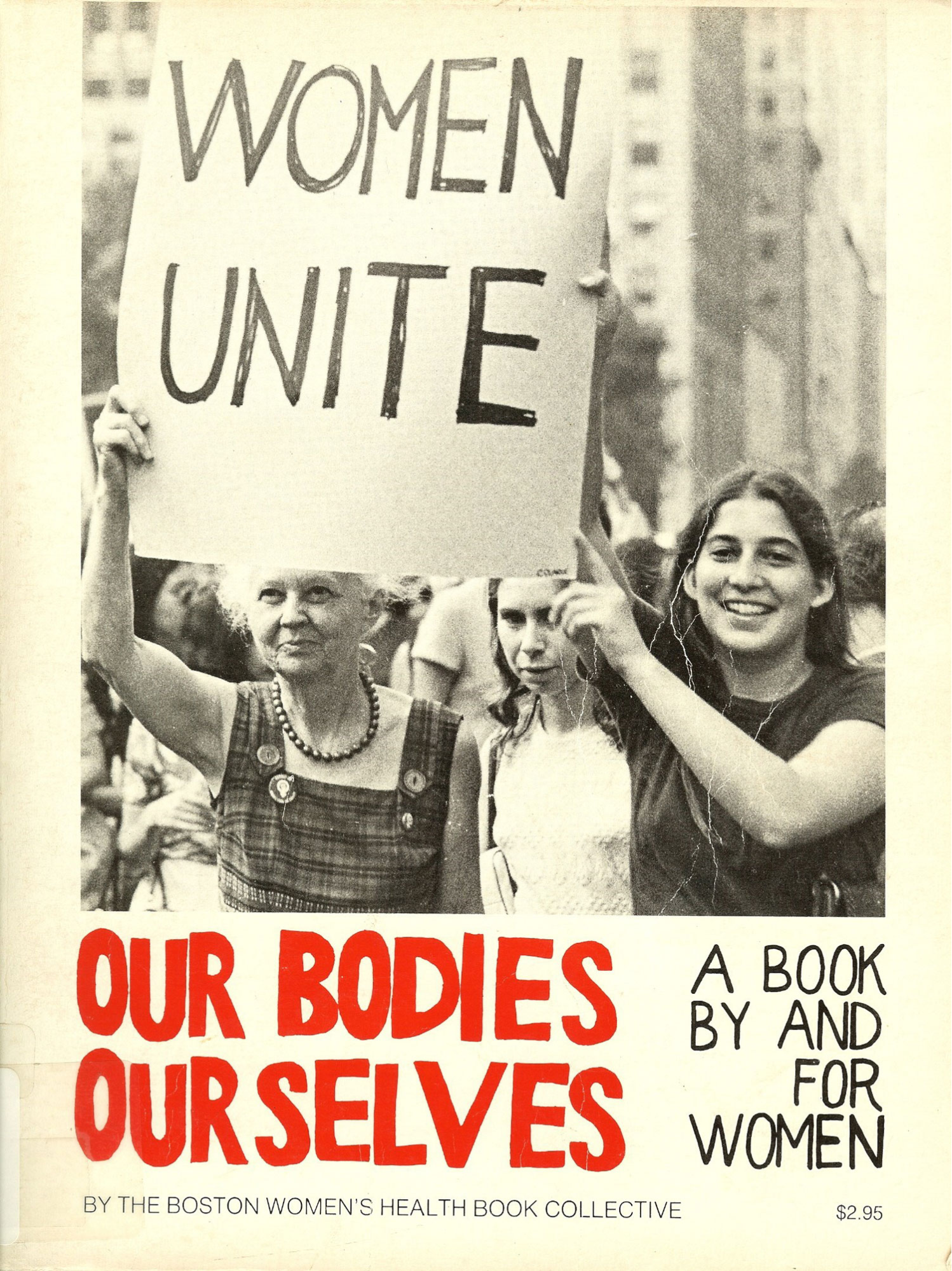

Figure 10.18. The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective published Our Bodies Ourselves to educate women about women’s health. Why would information like this increase reproductive justice?

Women have been sharing information about health forever, but this work became more focused with the 1970s women’s movement. A women’s collective wrote Our Bodies Ourselves to share concrete practical information about women’s health. In their work, they told each other stories about their first periods and how they learned about menstruation. Generally, information about periods had been shrouded in mystery and shame. The book challenges this mystery and shame related to women’s health, offering women clear, accessible information about health, information that wasn’t generally accessible at the time. This collective is still going strong today (Our Bodies Ourselves Today 2023).

Figure 10.19. Feminist activists continue to agitate for reproductive justice. In the Boston Women’s March in 2017, a protester wears a pussy hat and carries a sign that says ”Stop The War On Women.” Are there opportunities to create social justice through reproductive justice in your community?

Women’s commitment to reproductive justice didn’t stop with writing books and education. Feminists, including women, men and non-binary people, continue to work for reproductive justice. These efforts include supporting the 1973 Roe v Wade decision, which protected the right to have an abortion. More recently, this social movement generated several Women’s Marches on Washington D.C. and protests related to reproductive rights. The song “I Can’t Keep Quiet” became one of the anthems of recent women’s marches. Feel free to listen if you’d like.

Beyond education, writing and protesting, many organizations provide reproductive justice through healthcare services. SisterSong, the women of color reproductive justice coalition was formed in 1997 by 16 organizations of women of color. They write:

SisterSong’s mission is to strengthen and amplify the collective voices of indigenous women and women of color to achieve reproductive justice by eradicating reproductive oppression and securing human rights (SisterSong 2023)

They connect issues of gender, class, and race to create a national multi-ethnic movement to support reproductive justice, which includes not only access to safe abortion, but access to contraception, and freedom from forced sterilization. The organization collects funds and distributes them to birthing People of Color and queer or trans people who need birth support (Sistersong 2023).

Figure 10.20. Black Doulas improve maternal health outcomes for Black women and pregnant people. Why might demedicalizing maternal health care result in better outcomes?

Finally, midwives and birth doulas are offering options to ensure reproductive justice. Black Doulas, for example, help Black women and birthing people to have babies safely. This alternative is important to combat the racism in reproductive care, in which Black women are three times more likely to die than White women from pregnancy-related causes. A birth doula provides emotional and physical support to a pregnant person before, during, and after the birth. This culturally specific care improves outcomes for pregnant people:

As doula care is a proven, cost-effective means of reducing racial disparities in maternal health and improving overall health outcomes, policy advocates, legislators, and other stakeholders should undertake efforts to increase Medicaid and private insurance coverage of doula services. (Robles-Fradet and Greenwald 2022)

Reproductive Justice solutions include education, activism, and providing needed care. Reproductive Justice is social justice.

10.5.4 Interdependent Health Care Solutions to COVID-19

When you read about the numbers of people dying of COVID-19, the inequalities in meeting basic needs, or the reasons why children die more often in poorer countries, it is normal to feel overwhelmed by the depth and breadth of the social problems of health.

At the same time, our collective response to COVID-19 highlights our interdependence and our ability to create change. Even before COVID-19, health professionals highlighted how health for all requires acknowledging our interdependence. For example, in the article “The power of interdependence,” the authors write that connecting people, providers, and systems is essential:

Promoting optimal health outcomes for diverse patients and populations requires the acknowledgment and strengthening of interdependent relationships between health professions, education programs, health systems, and the communities they serve. (Van Eck et al. 2021)

Researchers have already started looking at how understanding the spread, treatment, and eventual recovery from COVID-19 can help us get better at solving social problems worldwide. In the article “System Thinking in COVID-19 Recovery,” the authors point out first that COVID-19 is targeting our most vulnerable people:

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have been experienced differently globally, regionally, and within countries. Rather than equalizing societies, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated existing inequalities on an unprecedented scale. The effect of the pandemic on vulnerable people is already, and will continue to be, devastating, especially in regions with particularly challenging economic landscapes, such as in Latin America, which has the highest levels of inequalities globally, and in sub-Saharan Africa, which has the highest levels of poverty. The U.N. stated that just 25 weeks of the pandemic derailed 25 years of human development. (Omukuti et al. 2021)

They further argue that women and girls are disproportionately impacted:

Lockdowns have led to increases in domestic violence and femicide and although all women are at risk of gender-based violence, women of poorer backgrounds have less resources to flee violent homes, whereas women who are older, disabled, migrant, Indigenous, Black, or minority ethnic are less likely to have access to protection services or obtain justice. Social distancing measures have put more women and girls out of paid work and education in comparison to their male counterparts due to gendered factors, such as prioritizing boys’ education or forcing girls into child or early marriages. (Omukuti 2021 et al. 2021)

Unexpectedly, though, the authors do not argue for public health interventions. The first strategy they propose is reducing the debt loads of lower-income countries so that more money can go to public health and infrastructure projects. The intricate interconnections of money and power connect countries together. By changing the accessibility of money, the authors argue, the circumstances of women and girls during the pandemic can be improved in the long term.

Closer to home, we see how individual agency and collective action can give us hope. In another bit of good news, some young people across the country are using their tech-savvy skills to help older people get COVID-19 vaccines, which can be difficult to schedule and require a certain amount of tech-savviness. 12-year-old Samuel Kuesch, a video game lover, has helped over 1,200 older Americans get COVID-19 vaccine appointments (Herzog 2021). His project expanded to his extended family, and teens and preteens in his family are now all pitching in to give older Americans a “shot at the shot.” Other examples include neighbors taking food to quarantine friends, food kitchens adding staff to provide more boxed meals and delivery to people who couldn’t leave home, and school art studios using 3-D printers to create PPE for understaffed hospital workers. Each individual action supported the collective good, improving health for all of us. We all deserve to be healthy. Actions that promote health are social justice.

10.5.5 Licenses and Attributions for Health Equity is Social Justice

Open Content, Original

“Health Equity is Social Justice” by Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Changing US Healthcare policy” and “Changing Healthcare Policies Around the World” are

adapted from “Comparative Health and Medicine” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Sustainability goals and covid detail was added.

Figure 10.16. “People Living in the US Who Are Uninsured” by Elizabeth B. Pearce and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.17. “Obamacare Protest at Supreme Court” by Tabitha Kaylee Hawk is licensed CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Figure 10.19. “Boston Women’s March 02” by Carly Hagins is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 10.20. “Photo of Black pregnant woman and man” by Andre Adjahoe is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 10.18. “Cover of the 1973 edition of ‘Our Bodies, Ourselves’” by The Boston Women’s Health Book Collective is included under fair use.