13.1 Chapter Overview and Learning Objectives

Kimberly Puttman

13.1.1 Learning Objectives

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

- Explain how death and dying is a social problem.

- Identify the cultural, social, and structural factors that impact death and dying.

- Apply the concepts of life course, ageism and a good death to explain inequalities in death and dying.

- Describe how religion creates the potential for conflict in values that is a characteristic of a social problem.

- Demonstrate how thanatology helps us understand the social problem of death and dying.

- Compare individual and collective action which expand the possibility of justice in the process of death and dying.

13.1.2 Chapter Overview and Learning Objectives

Note: With thanks to the people who make our lives and our deaths easier – the front line health care workers, spiritual care workers, and our families. We see you!

-Kim Puttman

Figure 13.1. COVID-19 Deceased in Morgue Truck 2020. So many people died unexpectedly from COVID-19 that even dealing with the bodies was a challenge to our health systems. How has COVID-19 challenged our expectations around a good death?

This chapter may be the most difficult chapter in the whole book. We will be exploring the social problems of death and dying. Some of us have lived with a lot of death in our lives. The experience is familiar, even though every death is painful. Some of us have never even thought about death, really. Whatever our experience, this chapter can bring up strong feelings and emotions. Please remember to practice good self-care as you walk with us through this material.

And, as much as we once knew about the process of dying and death itself, dealing with death during the COVID-19 pandemic brings its own set of challenges. Watch the video in Figure 13.2 to learn more about one family’s experience.

Figure 13.2. In this 6.50-minute video, Dying of Coronavirus: A Family’s Painful Goodbye [YouTube], a family talks about someone in their family who died of COVID-19. As you watch, please think about who was involved in this death. How does this death differ from what you might consider a good death? Finally, you might consider how providers and families respond to death from COVID-19. Transcript

To put this story in a wider context, over 767 million people contracted COVID-19 worldwide as of August 2023. Nearly 7 million people worldwide died from COVID-19. (World Health Organization 2023). That’s about half the population of the Pacific Northwest or just under twice the population of Los Angeles. Although some people would have died anyway, many of these deaths were unexpected. Sociologists call this pattern excess death, the difference between the observed numbers of deaths in a particular time period and the expected deaths for that same time period (CDC 2023).

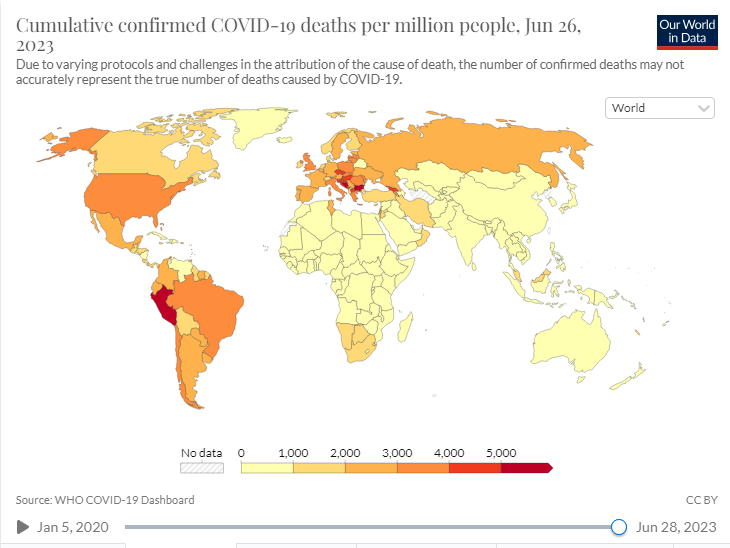

As we discussed in Chapter 10, the level of illness worldwide overwhelmed our healthcare system. The amount of unexpected death overwhelmed our end-of-life systems as well. Hospitals in New York and elsewhere needed to park morgue trucks in their parking lots to handle the number of bodies (Figure 13.1). Spiritual care staff, including chaplains, pastors, ministers, rabbis, and other religious leaders, performed funerals on Zoom and prayed over burials in uncountable numbers. Every country has been impacted by unexpected deaths due to COVID-19. You can see the cumulative death per million people on the map in Figure 13.3.

Figure 13.3. Global cumulative deaths from COVID-19, per million people, as of June 26, 2023. The country in which you live partially determines how likely you are to die from COVID-19. Image description

As we consider what may be the most personal of all human experiences, death, we also see that death is a social problem. With the map in Figure 13.3, we notice that where you live, by country, changes the likelihood that you will die of COVID-19. Even by this simple measure, death is also a social problem.

13.1.3 Focusing Questions

As we look deeper, the questions that guide our exploration are:

- How do we explain death and dying as a social problem?

- What are the cultural, social, and structural factors that impact death and dying?

- How does the concept of life course illuminate issues around aging and dying?

- How does the social institution of religion create the potential for conflict in values, a characteristic of a social problem?

- How does thanatology help us understand the social problem of death and dying?

- How are individuals and communities creating new possibilities of interdependent improvements to create social justice in the process of death and dying?

Let’s stare death in the face together!

13.1.4 Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Overview and Learning Objectives

Open Content, Original

“Chapter Overview” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 13.1. “COVID19 deceased in Hackensack NJ April 27” by Lawrence Purce is in the Public Domain, CC0.

Figure 13.3. “Global cumulative deaths from COVID-19, per million people, as of June 26, 2023” by the World Health Organization is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 13.2. “Dying of Coronavirus: A Family’s Painful Goodbye” by The New York Times is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.