14.4 The Sociology of Disaster Recovery

Kimberly Puttman

As we examine the sociology of natural disasters, we will present three models which explore the human consequences of disasters. The models include the cycle of disaster recovery, the mental health recovery paradigm, and resilience gentrification. Resilience gentrification is an intersectional theoretical approach to disaster recovery.

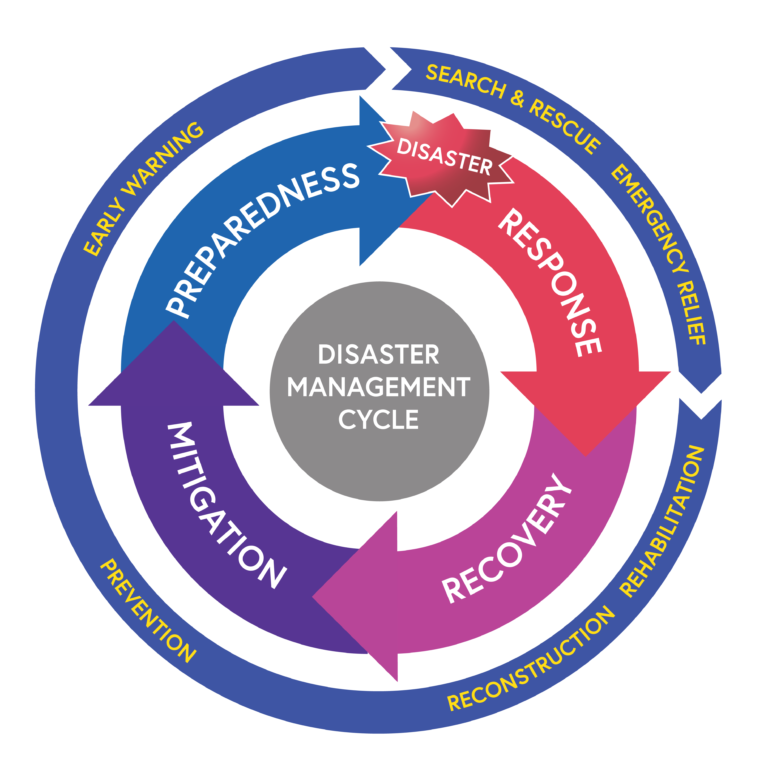

14.4.1 The Disaster Management Cycle

Figure 14.16. This diagram illustrates the disaster management cycle. Once the disaster occurs, the community responds immediately. When the initial disaster subsides, disaster recovery starts, but it often takes years for a community to recover. Ideally, communities learn from the disaster, mitigating any future problems and beginning to prepare for the next disaster. Image description

The disaster management cycle is a model that assists communities in thinking about disasters. The inner ring includes preparation, the idea that a disaster could occur. In this step, governments and agencies assess what kind of disasters are likely to occur, and put plans and supplies in place so that they can respond effectively. In the outer ring, we see that communities may put early warning systems in place so that they increase their ability to move people to safety in advance of a pending disaster.

The disaster occurs and is immediately followed by disaster response. Disaster response includes the activities that address the short-term, direct effects of an incident (FEMA 2013). The response includes immediate actions to save lives, protect property, and meet basic human needs. In the outer ring, we see that efforts focus on search and rescue to save people and emergency relief, the provision of temporary shelter, food, water, and medical, emotional, and spiritual support. If you would like to learn more about this step in the words of two young women who responded in Massachusetts, watch the 9.07-minute video How to step up in the face of disaster

. These sisters use better technology solutions to improve the way we respond to disasters.

For Otis, the responders included the fire departments and wildfire fighters who put out the fire. It included other first responders who helped with the ever-changing evacuations. It included the Red Cross, who managed initial temporary shelters and funded some of the survivors’ temporary housing. It included FEMA, who vetted survivors to see if they met federal qualifications. If so, survivors began the long process of accessing federal money and services. FEMA also provided a handful of housing trailers. Finally, disaster response included community organizations both locally and across the state.

The stories of Echo Mountain Fire Relief, Cascade Relief Team, The Grange, Landscaping with Love, and Latino Outreach are woven throughout this chapter. When we made a list, we saw that over 50 governmental, non-profit, community, and religious organizations took part in our recovery, in addition to all the individual people who showed up to help.

The next step, disaster recovery, includes rebuilding the affected community. Houses, schools, hospitals, roads, and electrical and water systems are reconstructed often to higher building standards than before. The infrastructure that was only partially damaged gets rehabilitated. Some people are able to return to new homes. This process can take years. It is also a process full of inequality.

For Otis, disaster recovery is still the current step, even two years later. The Red Cross left relatively quickly. People are still working through the FEMA process. However, the community organizations that engaged directly after the fire and subsequently grew are still supporting survivors.

The final step, mitigation, includes the forward planning and action needed so that the community can recover more quickly in the event of the next disaster. Often, this step includes expanding disaster resilience, a community’s ability to withstand a disaster, recover from it, and thrive after it (adapted from Arcaya, Raker and Waters 2020: 11.4).

To increase disaster resilience, many communities create a Long Term Recovery Group (LTRG), an umbrella group which oversees the recovery of an area after a disaster to ensure seamless communication and coordination of all the parties involved in recovery. These LTRGs coordinate survivor support in a community. They also look to the future and take action to increase community resilience and prevent harm in the face of the next disaster.

14.4.2 Disaster Mental Health

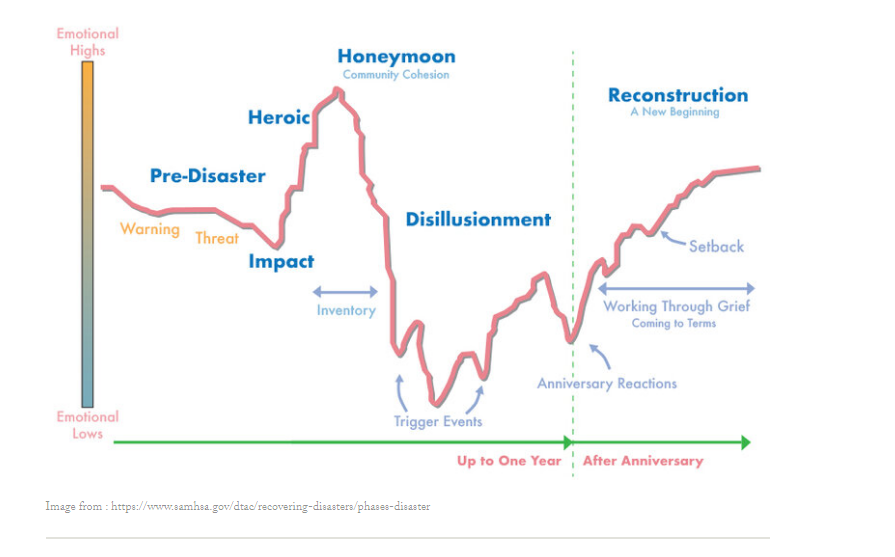

Figure 14.17. Emotional stages that people and communities go through related to a disaster. As you read the fire survivor stories in this chapter, where do you see the emotional highs and lows? Image description

In the previous section, we discussed the challenges to mental health that the people of Otis faced before, during, and after the Echo Mountain Fire. We recognized that mental health services were already in short supply and that the fire itself caused significant trauma. This trauma resulted in an even greater need for mental health services. In addition, sociologists see a relationship between pre-disaster health and post-disaster mental health. If your health was already challenged before the disaster, you are more likely to experience mental health challenges after the disaster (Arcaya, Raker; and Waters 2020: 11.9)

However, the mental health picture is more complex than that. As the chart in Figure 14.17 demonstrates, people experiencing disaster go through highs and lows. They experience stress before the disaster hits, as they try to gather information about what is going on and figure out what to do. Often, information conflicts. In Lincoln City, we heard that the whole north end of the town was burning when it wasn’t. In Otis, some families had only minutes to leave their homes. One recovery worker said that many survivors were barefoot because it took too long to put on shoes (Debbie 2023).

After the disaster hits and the initial panic begins to recede, survivors are grateful for the everyone who helped them. People who help are seen as heroes. Survivor emotions become more positive. However, it can take years for survivors to return home. As they realize how long the process will take and how hard it will be to recover, they are disillusioned. Seeing a similar event on TV can trigger traumatic feelings. The one-year anniversary of the disaster becomes another low point because it brings to mind the terror of the original disaster and the discouragement because of the lack of progress. Finally, although reconstruction and returning home are generally positive, emotional recovery takes time and energy. One person who supported survivors said that a common message from survivors once they returned home was, “This is my house, but it’s NOT my home” (Debbie 2023). In the process of moving in, they realized their life before the fire was really gone. The toll on their mental health was enormous. If you would like to learn more about the effects of disaster on mental health, watch this 5:10-minute video: How Natural Disasters Can Affect Your Mental Health [Video].

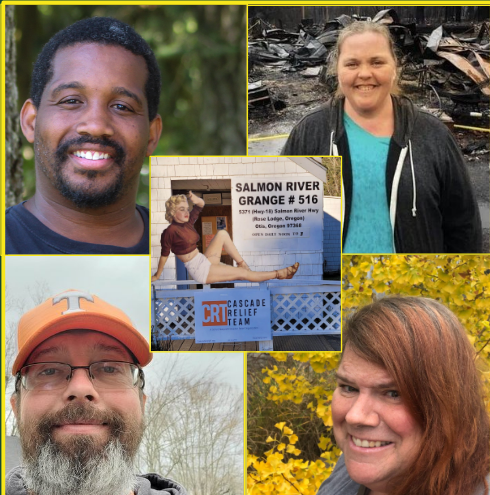

Figure 14.18. These people are the disaster recovery leaders who presented: Mark Brooks (upper left), Melanie Bright a CRT leader from the Holiday Farm Fire, a Labor Day fire in the Cascade Mountain Range (upper right), Josh Taylor, a CRT leader who experienced the Kentucky tornadoes of 2021 (lower left), Dr. Bethany Grace Howe (lower right) and Debbie, a Salmon River Grange leader that Marilyn Monroe is standing in for (center).

And feelings aren’t just for disaster survivors. They are for disaster recovery leaders too. CRT leaders pictured in Figure 14.18 presented “‘Via not Versus’ From Nothing to Everything: How to Lead When No One has to Listen” at a national conference for disaster recovery in 2023. In it, they discussed the problems that disaster relief leaders have to solve. One problem is that people who step up to lead in communities after a disaster don’t have official formal power. They lead because they are effective and people want to follow them, power to, not because they have power over them. This discussion of power is similar to the difference between power to and power over in Chapter 2.

These CRT leaders suggest that emotional intelligence and informed empathy are powerful tools in creating connections with survivors and with other relief leaders. All of us have been afraid, angry, sad, or elated. We can relate to similar feelings of other human beings, even when those feelings are caused by different events. This shared emotion allows us to form a connection with someone else. The connection is what allows us to think things through and act together. The CRT leaders say:

With Emotional Intelligence you can connect with people who may be unfamiliar to you via mutual feelings, not versus their experience which you may not now or ever share. (Howe, Brooks, and Bright, 2023: 48, emphasis in the original)

We see wise understanding of emotions and of trauma to make connections with survivors and people in other organizations so that we can work together. While disaster clearly takes a toll on mental health for both survivors and providers, understanding the challenges can help us solve them.

14.4.3 The Social Inequality of Disaster and Resilience Gentrification

Sociologists examine the inequalities present where people live. Early sociologists, including Marx, Weber, Durkheim, and Du Bois, who we met inChapter 3, examined the poverty in the city related to moving from rural to urban settings. Jane Addams, who we met in Chapter 1, not only studied the relationship of immigration and urbanization to social class and inequality, she did something about it.

When we apply these learnings to disasters, we see the same intersectional inequality at work. In a recent survey of the sociological work related to disasters, the authors write:

Social inequality shapes who is most at risk in disasters, with race, socioeconomic status, gender, and age all shown to affect vulnerability to disasters Social vulnerability can also be influenced by access to resources (e.g., economic, political, or information based), beliefs and customs, history, and other factors. Crucially, recent research stresses that social vulnerability is intersectional. In other words, it combines race, age, class, and gender, together with other conditions that create vulnerability; social isolation, poor physical or mental health, and precarious legal statuses create different levels of social vulnerability vis-à-vis different disasters. (Arcaya, Raker and Waters 2020: 11.5)

As you consider this quote, the message should be familiar by now. Intersectional inequality influences who is most at risk. More than that, intersectional inequality influences who recovers when. At the same time, this inequality plays out in unique ways when it comes to disasters. Let’s look deeper.

Figure 14.19 a and b. A Sociologists Kenneth Gould and B Tammy L. Lewis study the impact of climate disasters on coastal communities. They find that disasters widen existing inequities.

Modern sociologists continue the tradition as they examine the relationship between class and disaster recovery. Sociologists Kenneth Gould and Tammy L. Lewis, pictured in Figure 14.19, examined the relationship between wealth and recovery in Brooklyn, New York, after Hurricane Sandy and the island of Barbados, after Hurricane Irma. Prior to hurricane Irma, the authors were working with the government of Barbados to design participation action research that would discover what types of development projects the Barbudans wanted to do on their own island. You may remember participant action research from Chapter 4.

These sociologists focused on these two geographies because of a challenging paradox. On one hand, climate change is causing more severe storms and increased flooding. People in coastal areas are becoming more at risk of experiencing climate disasters. At the same time, about 40% of the population in the US and the world lives in coastal areas. These populations are increasing (Gould and Lewis 2021). The contradiction of more risk and increasing population creates an urgency in understanding the human effects of disaster and suggests options for mitigating the risks.

Gould and Lewis found that disasters resulted in resilience gentrification. Resilience gentrification is the process in which only the wealthy can pay the increased costs of building climate-resistant structures, resulting in displacing poorer people (Gould and Lewis 2021). Let’s learn more about this process.

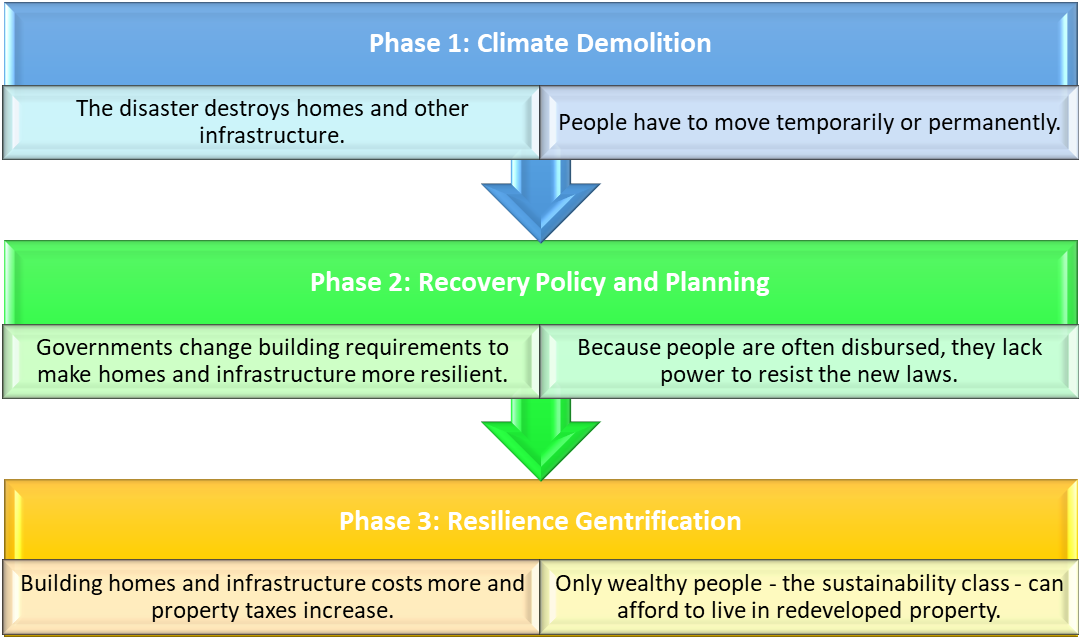

Figure 14.20. Disasters result in resilience gentrification. First, in Climate Demolition, the disaster destroys property. Second, in Recovery Policy and Planning, the government responds by changing the laws and policies to make sure that the new homes and infrastructure will survive the next disaster. Third, in Resilience Gentrification, the new homes cost more and have higher taxes because they were more expensive to build. The end result is that only wealthy people can afford to buy new homes. Image description

In Phase 1: Climate Demolition, the disaster destroys homes, roads, electricity, hospitals, schools, water systems and other infrastructure. The people in the area have to move either temporarily or permanently. This phase provides an opportunity to do things differently, whether it is to let the environment recover without rebuilding or rebuild in more sustainable ways. Often communities choose rebuilding resiliently.

In Phase 2: Recovery Policy and Planning, (mostly) well-intentioned governments change the rules so that communities are more resilient to disaster. Depending on the geography and the need, they may require that houses and buildings be raised higher than the floodplain. Electrical and plumbing infrastructure may be made of better materials or use more structurally sound building processes. These new building codes increase the disaster resilience of the new built environment. Usually, these changes cost money. Because the original residents are still dispersed, they can’t respond to or oppose the proposed changes to building codes.

In Phase 3: Resilience Gentrification, the new, more expensive homes, buildings, and infrastructure are built.Because the properties are more expensive, the property taxes are also more expensive. Therefore, only people who are wealthy can afford to buy property there. Gould and Lewis call these people the sustainability class They write:

The sustainability class is well-educated, holds overt sustainability oriented values, can afford sustainability themed consumption, and touts their green urbanism (such as living on the waterfront or near green spaces) to brand their lifestyle. (Gould and Lewis 2018: 12)

However, their analysis of the sustainability class goes deeper. This class of people is often White. Sometimes they make their money because they build eco-friendly buildings or own the factories that create eco-friendly products. Often they make their money precisely because they benefit from the labor of the working class. Gould and Lewis are explicit about this conclusion for the Brooklyn neighborhood that they studied:

Demographic analysis …reveals that structural mitigation, building “resilience,” is linked to gentrification. ….Housing prices for new construction exceeds the rate of Brooklyn housing cost increases, while the neighborhood shifts from a working-class community of color to a wealthy white enclave. A structurally mitigated, climate resilient [neighborhood] is increasingly available only to the sustainability class. (Gould and Lewis 2021)

We see resilience gentrification in Otis. Survivors like Betty sold their property because they couldn’t afford to rebuild. And as fire survivors come home, they live in new modular and stick-built homes. These homes are worth significantly more than their old homes, so they owe more property taxes. In some cases, they can’t afford to continue to live in these new properties. We also see that people with insurance generally recover faster. Because the amount of government aid is dependent on the original worth of your property, the wealthy, generally White people receive more payments and can rebuild sooner (Arcaya, Raker, and Waters 2020; Howell and Elliott 2019).

14.4.4 Licenses and Attributions for The Sociology of Disaster Recovery

Open Content, Original

“The Sociology of Disaster Recovery” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 14.20. “Disasters Result in Resilience Gentrification” by Kimberly Puttman, based on the work of Gould and Lewis, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 14.16. “The Disaster Management Cycle” by Coventry University is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Figure 14.17. “Phases of Psychological Reactions to Disasters” based on Zunin & Myers Stages of Disaster Recovery from Traumatic Stress and Suicide After Disasters (p. 8) by SAMHSA is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.18. “Image of Disaster Recovery Leaders” from “Via not Versus From Nothing to Everything: How to Lead When No One has to Listen” by Howe, Brooks and Bright is included under fair use.

Figure 14.19a. “Sociologist Kenneth Gould” © Kenneth Gould is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 14.19b. “Sociologist Tammy L. Lewis” © Tammy Lewis is all rights reserved and included with permission.