14.5 Community Recovery is Social Justice

Bethany Grace Howe and Kimberly Puttman

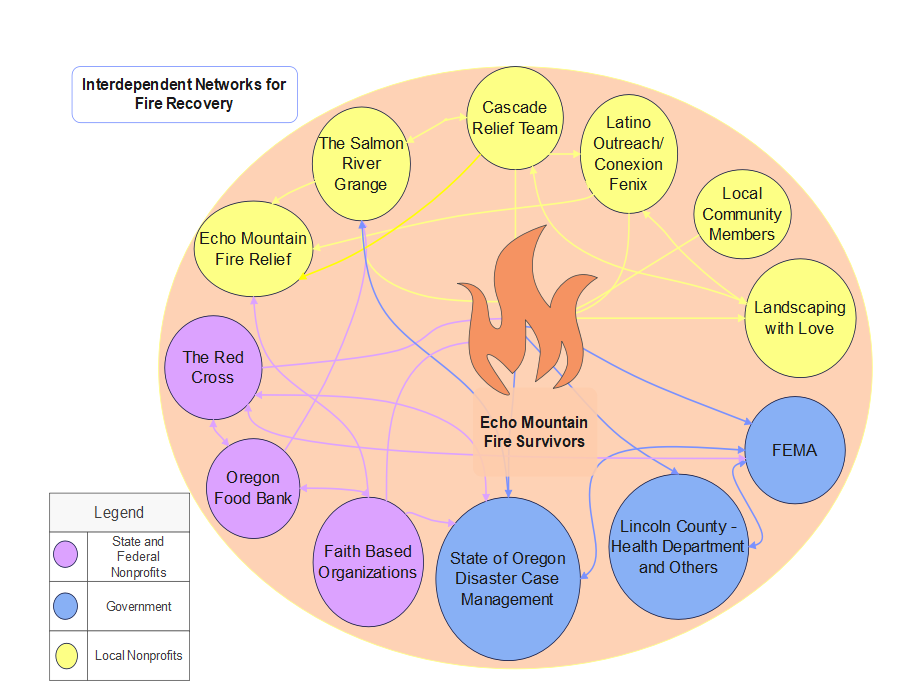

Figure 14.21. This diagram shows how governmental, non-profit, faith-based, and community actors all worked together to heal their community. Only some of the 50 organizations that provided relief are included here. If you think this diagram looks complicated, think about what it would be like if you were a fire survivor. Image description

Throughout these stories of survivors and survival, you have seen a huge cast of characters, from individual people, to local nonprofits, to community organizations, to statewide government and national relief organizations (Figure 14.21). But who actually came together, and what did they do?

Our survivors tell uncommon stories. Many of those who worked hardest to remove the debris from their neighbors’ lots on the burned hillside of Echo Mountain had lost everything to the fire as well. They chose to help their neighbor first, even as smoke still curled from the debris of their own home. As the recovery progressed, community members who had been limited by a lifetime of addictions and a history of trauma suddenly found themselves leading the people around them.

It was more than that, however. For even as the residents of Otis chose to do it themselves, other local groups and businesses were taking action, too. Some of them were century-old institutions, while others formed in the wake of the fire. All of them were fighting for Otis, usually before state and federal organizations could take action. In this section, we’ll look at how a community weaves itself together. In some cases, this community is stronger than before. In others, persistent structural inequalities and social conflict limit how far recovery can go. Let’s explore the specific ways that Otis leveraged individual agency and collective action to strengthen social justice.

14.5.1 Addressing Community Building: Echo Mountain Fire Relief

Figure 14.22. The logo of Echo Mountain Fire Relief emphasizes the organization’s role in connecting survivors and organizations.

As we discussed in the previous section, ensuring that survivors knew about services and service providers knew about each other took communication. The people of Otis got the help they needed starting even before the fires were out because the government worked with the churches, and nonprofits coordinated with small businesses. Researchers call this type of interaction between groups of similar size and levels horizontal communication. It sustained the people of Otis in the very first days of fire relief. Just as critical, however, to the continued recovery was vertical communication, those communications that cross up and down between organizational levels and groups of different sizes and authority (Serra et al. 2011:6).

The organization that became the communication hub for both horizontal and vertical communication was Echo Mountain Fire Relief (EMFR). EMFR was founded by a local business owner and volunteer firefighter. Over the next year, the organization would move into social services, even signing a contract with the State of Oregon to provide social services in the affected area. However, communication is what EMFR specialized in.

One of our most consequential connections was between The Grange, CRT, and Northwest Oregon Works (NOW). A local nonprofit, NOW had donated thousands of dollars to pay for groceries and other immediate needs for fire survivors. More importantly, they offered Dislocated Worker Grants. These grants from the Department of Labor allowed CRT and the Grange to hire fire survivor workers. NOW either paid employees directly or reimbursed CRT for their wages. Each person made $20 an hour, more than some of them had ever been paid in their lives. This ensured not only the success of The Grange, but also the Volunteer Clean-up, Landscaping with Love, and other north Lincoln County relief efforts.

14.5.2 Addressing Basic Needs: Salmon River Grange, Landscaping with Love, and the Cascade Relief Team

Figure 14.23. The Salmon River Grange. The mini-Walmart of Otis, where you can find food, sheets, tools, clothes, and even facemasks and hand sanitizer. Perhaps more importantly, survivors found people who would listen with love.

In the immediate days and weeks after the fire, donations poured in for the people of Otis. Every kind of household good was given, from appliances to clocks to dish towels. Non-perishable foods of all kinds, from cans of soup to sacks of potatoes. And clothes: every imaginable thing, to fit every imaginable person.

The sustained response to coordinating donations and ensuring that they got to survivors became The Salmon River Grange (“The Grange”), as pictured in Figure 14.23. Before the fire, this 104-year-old building was home to weekly bingo nights. Now, they are known as the survivor mini-Walmart. As soon as it was safe to return to this site, adjacent to the fire, the Grange was the place to go for food, water, clothes, and other household stuff, as shown in the image in Figure 14.24. More than that, it was a place that wove community, providing people who would listen and solve problems with survivors.

Figure 14.24. Shelves stocked at the Salmon River Grange. Even as late as 2023, survivors are still coming home and need all the basics.

This massive community response is not unusual in the days and weeks after a disaster. What happened in north Lincoln County was different from many communities, however, in how coordinated these efforts were. Although communication wasn’t perfect, people stayed in touch with one another. When a fire survivor needed something one donation site didn’t have, they knew who might. When the donations threatened to overwhelm one location, they knew they could make arrangements to send it to another.

As The Grange moves into disaster mitigation and preparation, its role in the community remains vital. Survivors still arrive every week for help. With mental health outreach, a food bank, internet access, and other services that just about any Otis resident needs, they are again what they started as more than a century ago – a center of community life.

Leaders at The Grange are envisioning the future. They are remodeling their kitchen so that the community of Otis can have access to a commercial kitchen. They hope that this will allow people to create products to sell at local farmer’s markets, strengthening the economic resilience of the area residents (Debbie 2023).

Landscaping with Love thrives also, with the support of The Grange, CRT, and a lot of volunteers. They get occasional visits from the Otis Strong Tigers, a group of fire-impacted students and school district staff brought together after the fire. The Otis Strong Tigers volunteer at both The Grange and the Greenhouse from time to time. Whether tending the plants outside or folding clothes inside, they’re among the dozens of people still giving of their time to fire survivors in Otis.

Finally, CRT became the umbrella organization that does the administration that keeps the lights on for The Grange and Landscaping with Love. They are still organizing clean-ups of survivor properties because removing the dead wood and brush takes time. They have moved their headquarters to Otis. Perhaps the most important sign of their continued commitment to social justice is that they are responding to disasters in Oregon, including the Bootleg Fire and the Blue River Fire, and to disasters nationwide, including the tornadoes in Kentucky.

14.5.3 Addressing Housing: County and State Action

Figure 14.25 a and b. A Lincoln County Commissioner Katey Jacobson and B Oregon District 10 State Representative David Gomberg work to increase disaster recovery and resilience, and reduce resilience gentrification. (Can you tell that we are a county partially supported by crabbing?)

Getting survivors home and supporting equity in our community takes governmental action also. Lincoln County Commissioner Kaety Jacobson and State Representative David Gomberg are two examples of people who are tireless in their advocacy. Jacobson spent time at the Grange listening to survivors and folding clothes. She used this knowledge to write and advocate for 18 million dollars of recovery funding. She initiated a partnership with Oregon State University to rebuild septic systems and wells (Jacobson 2022, Lucas-Woodruff 2022). Because of her work, and the work of others, Lincoln County will build two tiny home villages specifically for fire survivors (Jacobson 2022, Lucas-Woodruff 2022).

Re-homing fire survivors also takes a state response. For our Echo Mountain fire survivors and fire survivors across the state, State Representative David Gomberg also took action. He lives in Otis. While his house survived, the trees and brush on about half of his property were burned. This experience and his existing commitment to the people of Lincoln County energizes his drive to support changes in the laws and policies of the State of Oregon to support fire survivors.

In the most recent legislative session, he sponsored bills that supported changes to disaster recovery, wildfire relief, and emergency preparedness. For example, one bill requires insurers to pay at least 70% of property loss, even if the policyholder doesn’t have a precise inventory.

These efforts and many others are slowly returning fire survivors to new homes. They are beginning to build more affordable housing in north Lincoln County. For some survivors the new homes are even nicer than what they lived in before the fire. Being home again is truly a success.

14.5.4 Addressing Racism: Latino Outreach and Conexión Fénix

Figure 14.26. This is the logo of Conexión Fénix, the organization that grew out of the Latino Outreach efforts of Echo Mountain Fire Relief. In it, the phoenix rises from the ashes of the fire to create new life.

Formal disaster relief efforts have a long history of leaving out communities of color. As we have discussed particularly in Chapters7, 9, and 10, historical and current racism drives inequality. This racism occurs in recovery efforts and requires dedication and action to address. In Otis, the predominant community of color is the Latino community. Fernando’s leadership with the Latinx Outreach committee combatted the racism that Latino families experienced.

He assembled a team of people who created events that were culturally relevant to the Latino community. Survivors gathered for dinner on the lawn. They created art that depicted the disaster and their hope for recovery. The Latino Outreach group hosted an afternoon with mental health counselors specially brought in from Portland’s Latino community. They coordinated a disaster preparedness training in Spanish in which every family in attendance got a first-aid backpack, as well as a solar-powered radio and flashlight.

Eventually, Fernando’s advocacy efforts went beyond the Latino community. When the Disaster Case Management process broke down, impacting Latino and White survivors alike, it was Fernando who wrote the first letter to the state. The second letter, too, was from a family he worked with. With another two letters from The Grange and another from CRT, the five of them worked together with leaders to make changes in the program that benefited the entire community.

Beyond disaster recovery, the Latino outreach committee has taken on a life of its own. In August of 2022, the Latino Outreach portion of EMFR became a new group. Called Conexión Fénix, they are what Fernando and his team always dreamed was possible, a community group serving the Latino community of north Lincoln County. Conexión Fénix empowers the community through education from how to buy a home to how to prepare for a disaster to how to start a small business. This family has risen from the ashes and created an organization that helps their community thrive. Their logo, shown in Figure 14.26, illustrates how they soar.

From time to time, I still get to have dinner with Fernando and his family. My favorite evenings are when we sit out on the porch of Fernando’s beautiful new home, the one near the top of a small hill on the side of Echo Mountain. He and his family built it together. The grill smells of carne asada and other delicious food. Sometimes, some old friends from the Volunteer Clean-up even stop by. The smells from Fernando’s grill carry quite a ways down the hill. Smiling and laughing, I can’t help but think one thing: “I’m really glad I called Fernando.”

14.5.5 Litigating Justice: Holding Power Companies Accountable

The Labor Day 2020 fires were one of the worst natural disasters in Oregon history. Although they were partially caused by high winds and drought, some survivors sought to hold Pacific Power accountable also. They filed a class action suit that claimed that PacifiCorp failed to respond to the warnings of the governor’s chief of staff and state fire officials to turn off the power in some areas to prevent sparks from the power lines.

On June 12, 2023, a jury found that PacificCorp was negligent. They awarded more than $70 million dollars to the 17 plaintiffs, who sued on behalf of thousands of others in this class action suit. Once all of the people in the class action suit apply for compensation, the total cost of the negligence may be upwards of a billion dollars. This is the largest penalty a utility company in Oregon has ever faced for its negligence in starting wildfires. PacificCorp plans to appeal the ruling, so it is too soon to tell if any survivors will receive the money (Profita 2023; Thomas 2023; Watson 2023).

14.5.6 Licenses and Attributions for Community Recovery is Social Justice

Open Content, Original

“Community Recovery is Social Justice” by Bethany Grace Howe and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 14.21. “Interdependent Networks for Fire Recovery” by Kimberly Puttman and Valerie McDowell is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.22. “Logo of Echo Mountain Fire Relief” by Echo Mountain Fire Relief is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 14.23. “The Salmon River Grange” by an unknown author for Cascade Relief Team is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 14.24. “Shelves stocked at the Salmon River Grange” by an unknown author for Cascade Relief Team is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 14.25a. “Commissioner Kaety Jacobson” by unknown author is included under fair use.

Figure 14.25b. “State Representative David Gomberg” © David Gomberg for State Representative is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 14.26. “Logo of Conexión Fénix” © Marisol Martinez Garcia is all rights reserved and included with permission.