14.6 Chapter Summary

Bethany Grace Howe and Kimberly Puttman

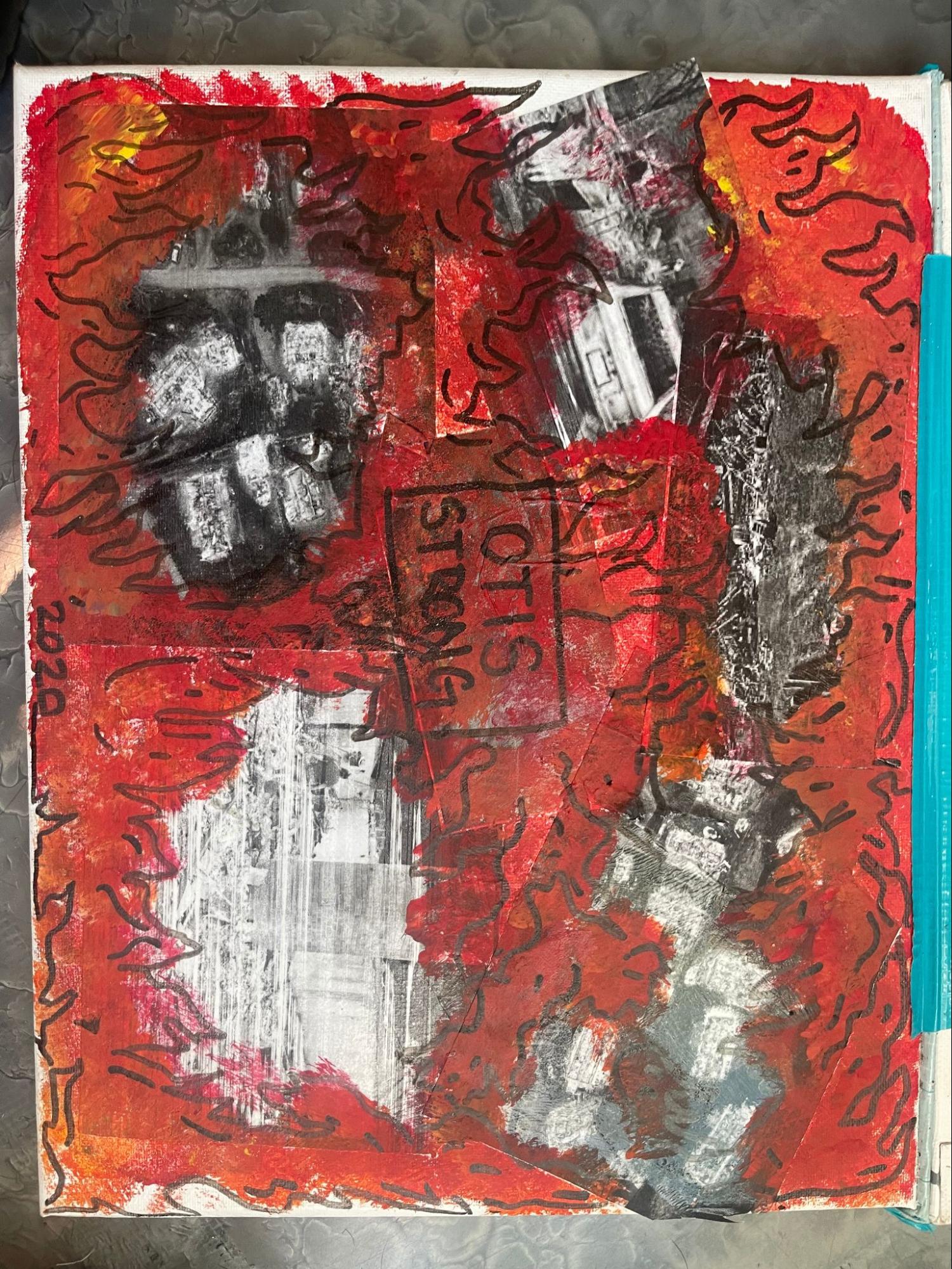

Figure 14.27. This painting of Otis Strong was created by a sociology student who was a fire survivor. In their art, they reflect suffering they still experience even years after the fire. They actually burned part of the canvas, so that the art piece would smell like smoke, creatively demonstrating the pervasiveness of their loss.

More than two years after the fire, the work continues. As late as January 2023, modular homes are still being delivered in Otis. Can we call this a success? It depends on how we measure. By the end of the fall of 2023, over 155 families had returned to put new homes on their properties. Some were built from the ground up. Most were modular homes or trailers. For some, it’s the nicest home they ever lived in. For nearly all of them, it is the only thing it needs to be: home. I spoke to someone just last week who had only been home for a few days. Every night, she said, she went out onto her deck. She’d forgotten what the stars looked like without city lights.

Over 100 families have found new homes away from Otis. Some bought new homes. Most relocated to apartments and other similar housing. Even before the fire, it was difficult to find affordable housing in Lincoln County, and after, it was nearly impossible. That most fire survivors were able to remain in north Lincoln County is remarkable. Dozens of others, however, have moved to other parts of the city, county, state, or country. Some did it because they had to. They couldn’t recover in Otis. For others, the fire was the impetus for change that they already wanted to make.

The connections that the survivors and supporters made with each other remain. We are no longer so disconnected. However, not every bond in Otis has improved with time. When the Volunteer Clean-up finally packed up their things with the arrival of state clean-up crews, some relationships went with them. Some of the original leaders of the effort have drifted apart. No longer tightly bound by the day’s mission of cleaning up one more home, and finding the funds to keep going for one more week, cultural and political differences once again define their relationships. But certainly not for everyone.

The transgender activist and the evangelical minister have dinner together when they can and talk about their lives and their beliefs. The Black leader from the Portland metro area is now living and working in Otis, bringing CRT to take action in disaster relief nationwide. Although our community is stronger, what happened to the fire survivors in our stories in the end?

As you might expect from the stories throughout this chapter, Fernando and his family are doing well. Fernando continues to work connecting Latinx families with the wider community, and to grow educational opportunities for everyone in Lincoln County. When I was at his house last week, his new crop of strawberries was almost ready to pick, and his first fruit trees were starting to blossom. He and his family remain deeply rooted in Otis, committed to creating community with all of us.

Carol and Tommy are still struggling. Carol left the fire survivor hotel without a solid plan. She returned to the insatiable life she had tried so hard to get away from. The last time I spoke to her, she was living in a friend’s attic. She said she hoped to only be there for a few days. Tommy is still living at the transition motel, struggling to find a home. The social problems he originally experienced limit his chances of returning home as well.

And Wendy and Betty? Their stories have come to an end.

When Wendy left the fire survivor hotel, one of her friends said to me she thought Wendy would be dead in a week. She was off by two days. Wendy returned to the life she’d fled the day of the fire, and died from a drug overdose

Betty died on Aug. 9, 2021. We held a memorial service with nearly two dozen people. When we were done, we walked to the beach and dropped the flowers in the receding tide. Betty had died living in a hotel alone, just like she feared she would.

Betty and Wendy died. Tommy and Carol have an uncertain future at best. From these four stories, it’s tempting to wonder if all of our individual and collective action was a failure. People died because they didn’t get what they needed. The four stories that concluded above are tragedies, and they speak to how social problems are sometimes nearly impossible to escape.

However, in the final analysis, we succeeded. EMFR started with one mission, to give donors a place to give their money. In the end, EMFR became a hub for communication, connecting survivors and providers so that the community became stronger. From that beginning, the Cascade Relief team was born. CRT continues to help locally and around the nation. The Grange is now managed by CRT and continues to support the basic needs of survivors, with the goal of supporting everyone in the community. Landscaping with Love is fighting climate change one plant at a time and hopes to open its nursery to the wider community. Latino Outreach, once an offshoot of EMFR, is now its own vibrant organization celebrating culture, dance, music, education, and connection.

EMFR itself is closed. This is actually a success. The organization did what it set out to do, distribute money and connect a community. Indeed, when I wrote the last check from the fund in August of 2022, I may not have known what people that money had gone to, but I knew what it had paid for. The last funds paid for an accessibility ramp for one family and a new trailer for a survivor who had been living in a hotel for two years. Two more families survived and thrived because the people of Otis did it together.

All of us are #OTISSTRONG!

14.6.1 Essential Ideas

Learning Objective 1: What social problems did people experience before the natural disaster?

The people of Otis were experiencing disconnection even before the Echo Mountain Fire. Many people in the community experienced all of the social problems explored in this book: educational inequality, high rates of homelessness, racism, and poor health, among other examples. Because of their physical location, they experienced less access to quality food, health, mental health, and drug treatment services. However, when we read survivors’ stories and explore the related demographic data, we learn that the truth of people’s lives cannot be reduced to general categories. Instead, each survivor is uniquely #OTISSTRONG.

Learning Objective 2: How does a disaster exacerbate existing complex social problems in a community?

When we experienced the dual disasters of wildfire and the COVID-19 pandemic, the underlying social disconnection made recovery much harder to achieve. Natural disasters, including the Echo Mountain Fire, expose existing social inequalities because people with less power and privilege have fewer personal resources to survive disasters and to support their own recovery. They may also find it more challenging to meet the complex and contradictory requirements to receive governmental recovery support. Often, the existing inequality gets worse because the destruction of existing infrastructure impacts the people with the fewest resources the most. In some cases, structural inequality may decrease. For example, many of the new homes now in Otis are newer and better than the structures they replaced.

Learning Objective 3: How do sociologists explain disaster and disaster recovery?

Sociologists use three models to explain disaster and disaster recovery. The disaster management cycle allows us to share a common understanding of the phases of disaster and disaster recovery. The disaster mental health model charts a path of mental health challenges for people and communities so that we can respond to mental health needs more effectively The concept of resilience gentrification links class, race, and disaster to provide a deeper understanding of how inequality is exacerbated (or not) after a disaster.

Learning Objective 4: How does the weaving of community after a disaster create opportunities for strengthening social justice?

Disaster wipes out physical and social infrastructure. As a community responds to the disaster, new organizations and new organizational relationships form, like Echo Mountain Fire Relief, The Grange, Landscaping with Love, and Conexión Fénix. Individuals come together in new ways, like the Volunteer Cleanup. Recovery in Otis is a long-term effort. These new social organizations and social networks resulted in re-homing many survivors and creating new ways of building a resilient equitable community. Although it is not common or guaranteed, disasters can result in social justice.

14.6.2 Key Terms List

- Community Organizations Active in Disaster (COAD): a local group of community organizations that coordinates emergency human services while working in concert with partner agencies, including the local emergency management agency and social service agencies, during all stages of a disaster.

- disaster recovery: the phase of the emergency management cycle that begins with the stabilization of the incident and ends when the community has recovered from the disaster’s impacts.

- disaster resilience: a community’s ability to withstand a disaster, recover from it, and thrive after it.

- disaster response: the activities that address the short-term, direct effects of an incident. The response includes immediate actions to save lives, protect property, and meet basic human needs.

- disconnected/disconnection: the breakdown of connections among and between people.

- horizontal communication: interaction between groups of similar size and levels.

- Long Term Recovery Group (LTRG): a unification of area groups brought together to oversee the recovery of an area after a disaster to ensure seamless communication and coordination of all the parties involved in recovery.

- resilience gentrification: the process in which only the wealthy can pay the increased costs of building climate-resistant structures, resulting in displacing poorer people.

- vertical communication: the communications that cross up and down between organizational levels and groups of different sizes and authority

14.6.3 Discuss and Do

- Disaster Response and Individual Agency If you had ten minutes to leave your home because of a natural disaster, what would you take with you? How many of the things recommended by the CDC in this infographic, Are you Prepared? do you already have?

- Disaster Recovery and Community Action: How prepared is your community? Do you have a long-term recovery group? What about a disaster recovery plan? Take some time to explore what resources your community already has in place for disaster preparedness and response. Can people of all social locations access these resources equally? If not, what would make a difference?

- Disasters, Power, and Privilege: As you read the stories of the survivors of the Otis wildfires, where do you see overlapping social problems? Do people recover equally?

- Interdependent Action for Social Justice: As you explore all the ways in which people, communities, and agencies responded to the wildfires and their aftermath, where do you see social justice in action?

14.6.4 Licenses and Attributions for Chapter Summary

Open Content, Original

“Chapter Summary” by Bethany Grace Howe and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 14.27. “Painting of Otis Strong, Burned” by Anonymous Student is all rights reserved and included with permission.