1.2 Defining a Social Problem

Kimberly Puttman

Figure 1.2. Sociologist Dr. Anna Leon-Guerrero. Her definition of a social problem includes both our social and our physical world. Why might this matter?

When you think about the current issues facing our society and our planet, you might name war, addiction, climate change, houselessness, or the global pandemic as social problems. You would be mostly right. However, sociologists need to be more specific than that. Because they are trying to explain what social problems are or how to fix them, they need a much more precise definition. Sociology professor and author Anna Leon-Guerrero (Figure 1.2) defines a social problem as “a social condition or pattern of behavior that has negative consequences for individuals, our social world, or our physical world” (2016:4).

More concretely, it is not just that one person gets sick from COVID-19. The social problem is that our healthcare systems are overwhelmed with sick patients. People are experiencing different rates of exposure to COVID-19. Their health outcomes differ because of their race, class, and gender. Because social problems affect people across the social and physical worlds, the solutions to social problems must be collectively created. It is not enough for one person to get well, although that may really matter to you. Instead, we must act collectively, as groups, governments, or systems, to identify and implement solutions. Our health is personal, but getting well depends on all of us.

To talk effectively about social problems, we must understand their characteristics. In this text, we will explore five important dimensions of a social problem You may encounter some new terms in this list. We’ll define them in the related section:

- A social problem goes beyond the experience of an individual.

- A social problem results from a conflict in values.

- A social problem arises when groups of people experience inequality.

- A social problem is socially constructed but real in its consequences.

- A social problem must be addressed interdependently, using both individual agency and collective action.

In the following section, we examine each of these five characteristics. Where these characteristics exist, social problems follow. Each component provides an additional layer of explanation about why any human problem is a social problem.

1.2.1 Beyond Individual Experience

Individuals have problems. Social problems, though, go beyond the experience of one individual. They are experienced by groups, nations, or people around the world. An individual experiences job loss, but the wider social problem may be rising unemployment rates. An individual may experience a divorce, but the wider social problem may be changing expectations around marriage and long-term partnerships. Solving a social problem is a collective task, outside of the capability of one individual or group.

Figure 1.3. Sociologist C. Wright Mills, pictured on the left, wrote about the Sociological Imagination.

In his book The Sociological Imagination, American sociologist C. Wright Mills helps us understand the difference between individual problems and social problems and connects the two concepts (Figure 1.3). Mills (1959) uses the term personal troubles to describe troubles that happen both within and to an individual. He contrasts these personal troubles with social problems, which he calls public issues. Public issues transcend the experience of one individual, impacting groups of people over time.

To illustrate, a recent college graduate may be several hundred thousand dollars in debt because of student loans. They may have trouble paying for living expenses because of this debt. This would be a personal trouble. If we look for larger social patterns, however, we see that as of 2021 about 1 in 8 Americans have student loan debt, owing about 1.6 trillion dollars (Federal Reserve Bank of New York 2021). The volume of this debt and the harm that is being caused stretch far beyond the experience of a few individuals. Student loan debt becomes a public issue.

In addition to differentiating personal troubles and public issues, Mills also connects them using the sociological imagination, a quality of mind that connects individual experience and wider social forces. He writes, “The sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. This is its task and its promise” (Mills 1959:6).

In other words when we use our own sociological imaginations, we start with our own lives, our biography. We connect with the experience of other people and their history. We consider how our own past actions and the historical actions of others may have contributed to our current reality. We use our sociological imaginations to consider what the outcomes of our actions or of social policies might be. When you use your sociological imagination, complicated social problems begin to make sense.

Figure 1.4. A society consists of more than individual people, just like a forest consists of more than just individual trees: The forest around Cougar Hot Springs, Oregon has more than just individual trees. Tokyo, Japan has more than individual people.

Building on Mills’s concepts, current sociologists highlight the complex relationships of the social world. In the 2019 Society for the Study of Social Problems Presidential Address, society president Nancy Mezey explores the topic of climate change as a social problem. Understanding and solving climate change requires a deep understanding of the relationship between people and systems. She emphasizes that “society is not just a collection of unrelated individuals, but rather a collection of people who live in relationship with each other” (Mezey 2020:606). To make this point, she uses the work of sociologist Allan Johnson. In his book The Forest and the Trees, Johnson compares the physical world to our social world:

In one sense, a forest is simply a collection of individual trees, but it is more than that. It is also a collection of trees that exist in particular relation to one another, and you cannot tell what that relation is by looking at the individual trees. Take a thousand trees and scatter them across the Great Plains of North America and all you have is a thousand trees. But take those same trees and put them close together, and now you have a forest.

The same individual trees in one case constitute a forest and in another are just a lot of trees. The “empty space” that separates individual trees from one another is not a characteristic of any one tree or the characteristics of all the individual trees somehow added together. It is something more than that, and it is crucial to understand the relationships among trees that make a forest what it is. Paying attention to that “something more” — whether it is a family or a society or the entire world – and how people are related to it lies at the heart of what it means to practice sociology. (Johnson 2014:11-12, emphasis added)

Using this comparison, Mezey reminds us that human society is made up of interdependent individuals, groups, institutions, and systems, similar to the living ecosystem of the forest. This similarity is illustrated in Figure 1.4. The reach of a social problem can also be planet-wide. As the response to COVID-19 demonstrates, migrations between countries, vaccination policies for any nation, and the responses of health systems in local areas can all impact whether any individual is likely to get COVID-19 or to recover from it. A social problem, then, is one that involves a wider scope of groups, institutions, nations, or global populations.

1.2.2 A Conflict in Values

Social problems can also be defined as issues where social values are in conflict. A value is an ideal or principle that determines what is correct, desirable, or morally proper. A society may share common values. For example, a society may value universal education, the ideal that all children should learn to read and write or, at minimum, be in school until they are 18. A different society may value practical experience, focusing on teaching children skills related to farming, hunting, or raising children. When core values are shared, there is no basis for conflict.

Social problems may begin to arise if people cannot agree on values. For example, some groups may value business growth and expansion. They oppose restrictions on pollution or emissions because following these regulations would cost money. In contrast, other groups might value sustaining the environment. They support regulations that limit industrial pollution, even when they cost more money. This conflict in values provides a rich soil from which a social problem may grow.

1.2.3 Inequality

A social problem can arise if there is a conflict between a widely shared value and a society’s success in meeting expectations around that value. For example, people need sufficient water, food, and shelter to sustain life. To work well, a society values human life and creates infrastructure so that all members have water, food, and shelter. However, even at this most basic level, people experience significant inequality in their access to these resources.

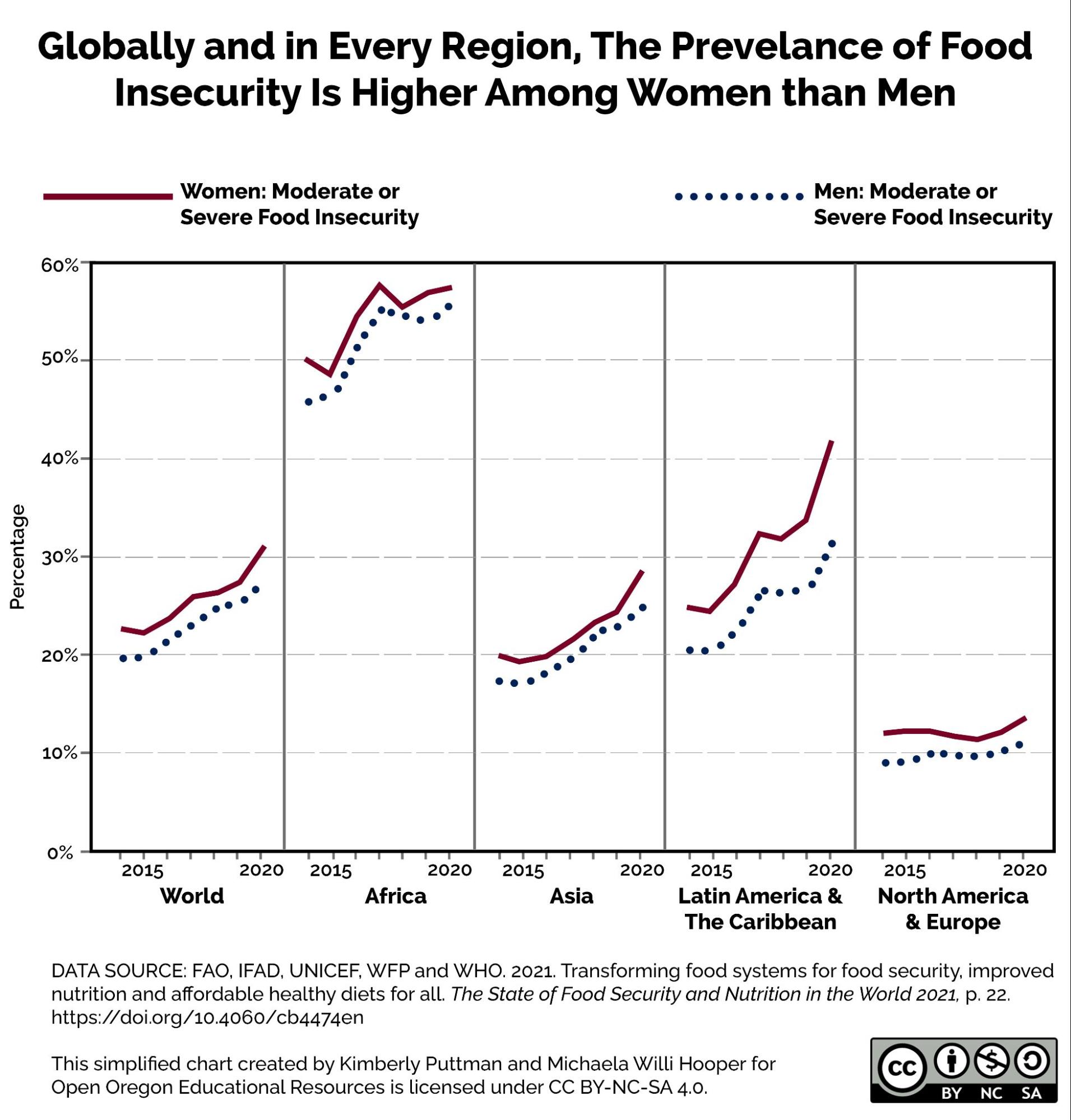

Figure 1.5. In this chart, we see that women experience more food insecurity than men, in every region of the world. In Africa, more than half of all people experience hunger. This rate of food insecurity has also increased around the world between 2015 and 2020. How do you think COVID-19 might have impacted world hunger? Image Description

For example, the United Nations reports that one in three people worldwide do not have access to adequate food. That number is rising (FAO et al. 2021). As we can see in the chart in Figure 1.5, women are more likely than men to experience hunger in all regions of the world. The related report also notes that 22 percent of all children worldwide are stunted because they do not have enough to eat (FAO et al. 2021).

In a local example, the Oregon Food Bank explicitly defines hunger as a social problem. They write, “Hunger isn’t just an individual experience; it’s a symptom of barriers to employment, housing, health care and more—and a result of unfair systems that continue to keep these barriers in place” (Oregon Food Bank 2021). In exploring who is hungry in Oregon, they note that communities of color experience greater housing instability and therefore greater food insecurity than White families (Oregon Food Bank 2019). Unequal access and unequal outcomes are both common in our world and fundamental to social problems.

1.2.4 A Social Construction with Real Consequences

Figure 1.6. This 11-minute video, Social Construction , explores what it means to jointly create our social reality. What else do you see that is socially constructed? Transcript

Sociologists delight in statistics, those numbers that measure rates, patterns, and trends. You might think that a social problem exists when things get measurably worse—unemployment rises, food prices increase, deaths from AIDS skyrocket, or gender-related hate crimes explode. Changes in the numbers, or objective measures, provide only part of the story. Sometimes these changes go unnoticed in the wider society. The changes don’t result in conflict or action. Other times one community takes action, but another community with similar statistics does not.

To explain this difference, we turn to the fundamental sociological concept of social construction. Social constructions are shared understandings that are jointly accepted by large numbers of people in a society or social group. This concept asserts that while material objects and biological processes exist, it is the meaning that we give to them that creates our shared social reality. The video in Figure 1.6 provides more examples of this concept.

Austrian-born American sociologist Peter Berger and American-Austrian sociologist Thomas Luckmann introduced the term social construction in 1966. They wrote a book called The Social Construction of Reality. In it, they argued that society is created by humans and human interaction. These interactions are often habits. They use the term habitualization to describe how “any action that is repeated frequently becomes cast into a pattern, which can then be … performed again in the future in the same manner and with the same economical effort” (Berger and Luckmann 1966). Not only do we construct our own society, but we also accept it as it is because others have created it before us. Society is, in fact, habit.

For example, a school building exists as a school and not as a generic building because you and others agree that it is a school. If your school is older than you are, it was created by the agreement of others before you. By employing the convention of naming a building as a school, the institution, while socially constructed, is made real and assigned specific expectations as to how it will be used.

Another way of looking at the social construction of reality is through an idea developed by White American sociologists Dorothy Thomas and William Thomas. The Thomas theorem states, “If [people] define situations as real, they are real in their consequences” (Thomas and Thomas 1928). In other words, people’s behavior can be determined by their subjective construction of reality rather than by objective reality. Let’s look at two examples.

Figure 1.7. What do you think the person in the photo, gesturing “Thumbs up,” is trying to say? Depending on his country, he may be saying great, one, or five. Even our hand gestures are socially constructed.

Sociologists who study how we interact recognize that language and body language reflect our values. If you have learned a foreign language, you know that every word does not translate easily. The same is true for gestures. What does the gesture in Figure 1.7 mean? While Americans might recognize a thumbs-up as meaning great, in Germany it would mean one, and in Japan, it would mean five. Thus, our construction of reality is influenced by our symbolic interactions.

Another example of the social construction of language is at work in this book. You might have noticed that we capitalize the words Black and White when we discuss race. We follow the work of Black historian Ibram X. Kendi, who writes: “Very simply, I capitalize both Black and White (and Brown for that matter) to distinguish between the races from the colors (2019).” The National Association for Black Journalists recommends this usage as well.

On the other hand, one of the textbook reviewers pointed out that writing “white” with a lowercase “w” is preferred by some people who work to end racism. Robin DiAngelo explains the conflict this way: “On one hand, capitalizing “Black” but not “white” interrupts the historical elevation of white above black. On the other hand, not capitalizing “white” minimizes its power as a racial category and reinforces white as the default” (DiAngelo 2021:xviii). White is as much a racial category as Black. So which do we choose?

In this book, we have chosen to follow Kendi’s advice. Every time we read “Black” or “White,” our brains might pause for a moment to remember that race is a socially constructed category with real social consequences. When we are conscious of social construction at work in language, we choose our words mindfully.

Already we see that not all social constructions are universally shared. Sometimes, our ideas about what is real or true in society are in conflict. Sometimes, those ideas change. Even when we agree that a social problem exists, we may not agree on what it is. In the next section, we look at how a social construction can change.

1.2.5 Unpacking Oppression, Advocating for Social Justice: The Social Construction of Rape

Figure 1.8. In this picture of social protest, the protester is holding a sign, “Whatever we wear, wherever we go, Yes means Yes and No means No.” Over time, our ideas about bodily autonomy, consent, and gender-based violence are changing.

In this class, we address sensitive social problems. Many of us are survivors of sexual violence, natural disasters, houselessness, and other painful experiences. If you need to skip this material for any reason, please do so. If it raises strong emotions, please talk to your instructor or reach out to your college mental health services. You are not alone.

We can see that the social problem of rape is socially constructed because our ideas change over time. Initially, European courts and lawyers defined rape as a crime of property. This view of women’s bodies is profoundly disturbing to us today but was common in seventeenth-century English law. Legally, women were considered the property of their fathers or their husbands. Therefore, rape was legally understood as decreasing the value of their property. Taking this model further, married women could not be raped by their husbands because consent was implied as part of the marriage contract.

When feminists in the 1970s challenged this legal definition, laws related to rape began to change. Rape, which included marital rape, became defined as a crime of violence and social control against an individual person (Rose 1977). In a more recent study, researchers examined how rape was defined in a college community between 1955 and 1990 (Abu-Odeh, Khan, and Nathanson 2020). Early descriptions of rape in school and community newspapers painted the picture that White women students were safe on campus. If they ventured beyond campus to predominantly Black neighborhoods, they risked being raped. Although this assumption was wrong, people believed that rape was a crime committed by a Black or Brown man who was a stranger rather than by a White man who the survivor already knew. This story relied on the false racial myth that Black men were dangerous. In addition, from this perspective, the police were responsible for keeping White women safe (Abu-Odeh, Khan, and Nathanson 2020).

With the work of feminist activists, the concept of rape and the response to rape changed. In the 1970s and 1980s, women’s centers and health professionals defined rape as an act of sexual violence that supported the power of men and an issue that threatened women’s health. The person who experienced rape began to be called a survivor rather than a victim. Men who raped or committed other kinds of sexual harassment could be identified as part of the campus community rather than being defined as strangers. Changes in the social construction of rape allowed for more effective community responses in preventing rape, prosecuting rape, and supporting the healing of rape survivors (Abu-Odeh, Khan, and Nathanson 2020).

Figure 1.9. Black activist Tarana Burke is the founder of the #MeToo Movement. How has #MeToo changed your willingness to talk about sexual violence or to take action?

Feminist activists continue this work. Black activist Tarana Burke founded the #MeToo movement in 2006 so survivors of sexual violence could tell their stories. These stories highlight how common sexual violence is for women, nonbinary people, and men. It expands our conversation about rape to a wider discussion around the causes and consequences of sexual violence. If you would like to learn more about #MeToo from Burke herself (Figure 1.9), please watch this TED Talk, “Me Too Is a Movement, Not a Moment .” Actor Alyssa Milano drew attention to this movement when she tweeted #MeToo in 2017. You might want to explore the #MeToo Twitter thread. This movement has resulted in some changes in the law (Beitsch 2018) and in stronger prosecution of perpetrators of sexual violence in some cases (Carlsen et al. 2018).

In this constructionist view, the definition of rape, the actors in the crime, and the responsibility for fixing the problem changed over time, with significant consequences for the people involved. Even concepts like consent, a freely given agreement to do something (Planned Parenthood 2015), are taught and learned (see Figure 1.8). We will see the usefulness of the social construction of a social problem as we explore each social problem raised in this book.

It’s your turn to unpack oppression and advocate for social justice:

Instructions

The concept of consent is often applied to sexual activity because sexual assault is partially defined by lack of consent. However, teaching consent is an important way to disrupt rape culture. Even young children can begin to learn about consent and bodily autonomy. How might teaching consent be a way to advocate for justice?

Please watch one of these three videos:

Grade One Teacher Welcomes Students With Special Greeting[Video]

A Cup of Tea and Consent [Video] (some adult language)

How Do You Know if Someone Wants to Have Sex with You? [Video]

As you watch, consider the social construction of consent.

Activity

Consider these questions:

- How do these videos change your thinking about consent?

- How might consent apply in your classroom or community?

- How does teaching and using consent create social justice by disrupting rape culture?

1.2.6 Interdependent Solutions of Individual Agency and Collective Action

All life is interrelated. We are all caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied into a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. We are made to live together because of the interrelated structure of reality. This is the way our universe is structured, this is its interrelated quality. We aren’t going to have peace on earth until we recognize this basic fact of the interrelated structure of all reality.

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., activist, sociologist, and minister

Figure 1.10. Video: Martin Luther King Jr. A Christmas Speech: Martin Luther King Jr. asserts that we are all interrelated, another word for interdependence, in his 1967 Christmas Speech. While watching the whole speech is optional, you may want to view minutes 7:10-8:47 to listen to this concept. Transcript

Our diversity can be a source of innovative solutions to social problems. At the same time, the ways in which we are different divide us. We see bullying, hate crimes, war, gender-based violence, and other patterns of treating each other differently based on our group membership. At the same time, many of us go to school, raise families, live in neighborhoods, and die of old age. How is it that we can maintain our sense of community?

We begin to answer this question by reminding ourselves that the sociological imagination helps us to see wider social forces at play in our individual lives. Interdependence is the concept that people rely on each other to survive and thrive (Schwalbe 2018). Martin Luther King Jr. asserts that we are all interrelated, another word for interdependence, in his 1967 Christmas Speech in Figure 1.10. Please watch at least minutes 7:10-8:47 to learn more about this concept from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. himself.

Interdependence is everywhere, but specific examples of social, economic, and physical interdependence may help us see it more clearly. With social interdependence, we rely on other people to cooperate to support our life. We give the same cooperation to others in turn. Sociologists sometimes call this kind of social interdependence social integration (Berkman et al. 2000)

For example, when you consider your own life, you might notice how many people helped you become the person you are. When you were a baby, you needed an adult to feed, clothe, and keep you warm. Maybe you were lucky, and someone read you bedtime stories. As we widen this picture, we see that your caregivers relied on store owners, doctors, farmers, truckers, business people, and friends to support the work of caring for you. You may not have had a happy childhood, yet you lived long enough to read these words. This book was brought to you by authors, editors, artists, videographers, designers, musicians, librarians, and other students like you. These relationships demonstrate our social interdependence.

In addition to social interdependence, we experience economic interdependence. As we shop for groceries this week, we see empty shelves and rising food prices. COVID-19 is disrupting the global supply chain. Some farmers in Mexico and South America can’t get their food across the US border (Lopez-Ridaura et al. 2021). US car manufacturers can’t get electronic chips manufactured in China. Even when people in Vietnam sew T-shirts or factory workers in Korea build TVs, the ships that carry these products from one country to another wait for dock workers to unload them. Our experiences with COVID-19 underline the truth of our economic interdependence.

We express this economic interdependence in relationships that describe the power of workers and the power of business owners. Power is the ability of an actor to sway the actions of another actor or actors, even against resistance (Fox Piven 2008). In 2017, Francis Fox Piven, the president of the American Sociological Association, defined interdependent power, arguing that while wealth and privilege create power, workers, tenants, and voters also have the power of participation. We see interdependent power today in the Great Resignation, with people deciding to resign from their jobs rather than return to work. We see it in restaurants reducing hours or closing down because they can’t find workers to wait tables and bus dishes. We see this in frontline workers becoming even more critical in providing basic services to a quarantined public. We live in a globally interdependent economy.

Finally, and maybe foundationally, we are physically interdependent. I remember being on a boat in a glacial lake in Alaska. The tour guide, a biologist, was asking the people on the tour about how many oceans there were in the world. All of us were desperately trying to remember fifth-grade geography, and counting the various oceans we remembered. Atlantic, Pacific, Indian . . . wait did the Arctic and Antarctic count as oceans? Maybe five? Maybe six? Maybe seven? At each answer, the biologist shook her head, “No.” We were stumped.

Figure 1.11. The Pacific Ocean at Lincoln City, Oregon, or maybe just one view of our planet’s one ocean. How do you see social, economic or physical interdependence in your own life?

She revealed that scientists who study the ocean now say that we have just one ocean (even though the ocean in Figure 1.11 happens to be the Pacific Ocean, a few blocks from my house). It contains all the ocean water across our entire planet. Debris from a tsunami in Japan washed up on beaches from the tip of Alaska to the Baja peninsula and Hawaii. Rivers contribute up to 80 percent of the plastics pollution found in the ocean. We see that the COVID-19 virus travels with people around the world as infections move from place to place. As we cross the globe on our feet, bikes, camels, trains, cars, and airplanes, our diseases travel with us. We are physically interdependent.

Figure 1.12. When do we comply with the social norms of mask-wearing and elbow-bumping?

Each of these ways of considering our interdependence matters when studying social problems and creating change. Because our actions affect one another, any social problem or solution ripples through our social world. For example, social scientists are examining mask-wearing during COVID-19.

Behavioral economics researcher Dr. Vera te Velde from the University of Queensland explores mask-wearing behavior around the world. She wanted to find out what would make wearing a mask a social norm. Social norms are the rules or expectations that determine and regulate appropriate behavior within a culture, group, or society.

Dr. te Velde finds that when people trust each other and their government, they are much more likely to wear masks. Trust and shared agreement around social norms encourage consistent behavior. In other words, when we notice our interdependence and trust that others will follow social norms, we are more likely to follow them too. If you want to learn more about Dr. te Velde’s research, watch “The Importance of Social Norms” (episode 8).

Sociologist Michael Schwalbe, in The Sociologically Examined Life, calls this mindfulness of interdependence. When we are aware, or mindful, of how our actions impact others, we are noticing our interdependence. We then often act for the good of all. In a more explicit analysis of racism, Black author and activist Heather McGhee argues that we collectively benefit when we organize for social justice across race, class, and gender divides. This solidarity dividend is reflected in the gains that come when people work together across their differences to accomplish what we can’t do individually (McGhee 2021) and improve everyone’s lives.

Figure 1.13 a and b. Fight for $15. As you look at these pictures representing Fight for $15, who do you see represented? Multiracial coalitions leverage interdependence to build social justice.

The organization Fight for $15 (Figure 1.13 a and b) is working to increase the minimum wage to at least $15.00 an hour. They deliberately name racism as a cause of division and multiracial unity as a source of power. One organizer says:

We’ve got to build a multiracial movement, a different kind of social justice movement for the [twenty-first] century. And we’ve got to talk about it, multiracial organization and how to build the movement, you know. (Fight for $15 activist Terrance, quoted in McGhee 2021:132)

These organizing tactics that emphasize our interdependence are working. As of May 2023, we’ve seen new increases to the minimum wage in eight states. In 2019, a bill passed in the US House of Representatives to raise the minimum wage to $15.00 across the country. It didn’t pass the Senate, but even the partial win is progress (Fight for $15 2023).

The interdependent nature of social problems also requires interdependent solutions. For this, we look at individual agency and collective action. The discipline of sociology always asks why? But the sociologists who study social problems are particularly committed to taking action. They try to understand why a problem occurs to inform policy decisions, create community coalitions, or support healthy families. In the best cases, they seek to know their own biases and work to remediate them, so their research is used to create change. This challenge is explicitly stated by SSSP President Nancy Mezey:

The theme for the 2019 SSSP [Society for the Study of Social Problems] meeting is a call to sociologists and social scientists in general to draw deeply and widely on sociological roots to illuminate the social in all social problems with an eye to solving those problems…. I am calling on you, the reader, through this presidential address to focus on what is perhaps the largest social problem: climate change. Indeed, because we have been focusing on individual rather than social solutions regarding climate change—we are now facing grave and imminent danger. (Mezey 2020:606)

Mezey tells us that studying problems is not enough. We must focus on the most critical social problem of climate change to support all of us in taking action.

Addressing social problems requires individuals to act. Social agency is the capacity of an individual to actively and independently choose to create change. In other words, any individual can choose to vote, protest, parent well, or be authentic about who they are in the world. Your choice may be limited by your race, class, or gender, among other identities, but each act of positive social agency matters to you and your community.

Collective action refers to the actions taken by a collection or group of people acting based on a collective decision (Sekiwu and Okan 2022). These kinds of actions people take are creative responses to local issues. We typically think of collective action as a protest march or a social movement. Collective action can also be setting up the Salmon River Grange as the distribution center for food, clothes, and pizza for survivors of the Echo Mountain Fire. It could also be reinvigorating an Indigenous language or connecting businesses and nonprofits so you can provide digital literacy skills training. People, communities, and organizations imagine the future they want to see and take organized action to make it happen.

To confront the social problems of our world, we need a both/and approach to their resolution. We act with individual agency to create a life that is healthy and nurturing, and we act collectively to address interdependent issues. We act to create social justice, full and equal participation of all groups in a society that is mutually shaped to meet their needs (Bell et al. 2007:1). You will have opportunities to more deeply understand oppression and engage in social justice throughout this book, in features like the Unpacking Oppression, Advocating for Justice activity earlier in this chapter.

1.2.7 Licenses and Attributions for Defining a Social Problem

Open Content, Shared Previously

“A Social Construction with Real Consequences” is adapted from “Social Construction of

Open Content, Original

“Defining a Social Problem” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Social Construction” definition from “Social Construction ” by Elizabeth Pearce, Kimberly Puttman, and Colin Stapp, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.5. “Chart of World Hunger” by Kimberly Puttman and Michaela Willi Hooper, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Figure 1.6. “Social Construction ” by Elizabeth Pearce, Kimberly Puttman, and Colin Stapp, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 1.11. “Photo of the Pacific Ocean at Lincoln City, Oregon” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Reality” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to social problems.

“Norm,” “Social Agency,” and “Value” definitions from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell are licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 1.3. “Sociologist C Wright Mills” by Institute for Policy Studies is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 1.4a. “Photo” by Deric is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.4b. “Photo” by Chris Chan is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.7. “Photo” by Aziz Acharki is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.8. “Photo” by Raquel García is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.9. “Tarana Burke” by Marco Verch is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 1.12. “Photo” by Maxime is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 1.13a. “Photo” by SEIU Local 99 is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

Figure 1.13b. “Photo” by SEIU Local 99 is licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.2 “Photo of Dr. Anna Leon-Guerrero” © Pacific Lutheran University is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 1.10. “Martin Luther King, Jr., Christmas Sermon” by Mapping Minds is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.