11.4 Five Models of Addiction

Kelly Szott

In this section, we explain the five models of addiction that are dominant in US society: the moral view, the disease model, a public health perspective, a sociological approach, and an intersectional approach. We will discuss these five views or models in this section, as well as where these models can be found in action within society.

11.4.1 Moral View

The moral view depicts the use of illicit substances and the state of addiction as wrong or bad. Illicit drug use is understood as a sin or personal failing. Faith-based drug rehabilitation programs are one location where we see the moral model in use. Through qualitative interviews with individuals who had attended such a facility, Gowan and Atmore (2012) found that within the teachings of evangelical conversion-based rehab, substance use is thought to be rooted in immorality. This requires the user to convert and submit to religious authority to recover. Gowan and Atmore (2012) found that the program implied that the root of addiction was in secular or nonreligious life. The rigid structure of faith-based drug treatment programs can be helpful for some people in recovery. Some people also find that faith-based community programs like twelve step programs are effective.

|

Schedule |

Definition |

Examples |

|

Schedule I |

No currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse. |

Heroin, LSD, and cannabis |

|

Schedule II |

High potential for abuse, with use potentially leading to severe psychological or physical dependence. These drugs are also considered dangerous. |

Vicodin, cocaine, methamphetamine, methadone, hydromorphone (Dilaudid), meperidine (Demerol), oxycodone (OxyContin), fentanyl, Dexedrine, Adderall, and Ritalin |

|

Schedule III |

Moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence. Abuse potential is less than Schedule I and Schedule II drugs but more than Schedule IV. |

Tylenol with codeine, ketamine, anabolic steroids, and testosterone |

|

Schedule IV |

Low potential for abuse and low risk of dependence. |

Xanax, Soma, Valium, Ativan, Talwin, Ambien, and Tramadol |

|

Schedule V |

Lower potential for abuse than Schedule IV and consist of preparations containing limited quantities of certain narcotics. Generally used for antidiarrheal, antitussive, and analgesic purposes. |

Robitussin AC with codeine, Lomotil, and Lyrica |

Figure 11.12. The Federal Drug Schedule. Which drugs that impact human behavior are on this list? Which ones are missing?

The moral view toward drug use can also be seen in our criminal justice system and the criminalization of drug use. Criminalization is the act of making something illegal (Definition of Criminalize 2023). The 1970 Comprehensive Drug Abuse and Control Act (US House 1970) created drug categorizations, called schedules, based on the drug’s potential for abuse and dependency and its accepted medical use. This new system of categorization acknowledged the medical use of some drugs while heightening the criminalization of other drugs (Figure 11.12). Drug policy in the United States is guided by the moral view of drug use. It calls for those who use substances to be punished, whether it is through fines, some form of home arrest, or incarceration.

11.4.2 Disease Model

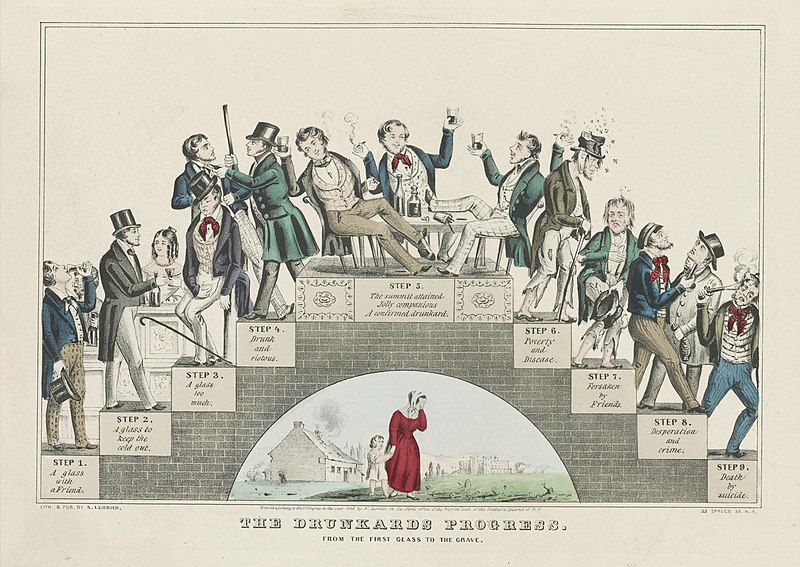

Figure 11.13. The Drunkard’s Progress, an 1864 lithograph by Nathanial Currier, shows the progression of alcoholism as a disease. By organizing the information into careful steps, the illustrator uses the trappings of science to popularize the disease model.

Understanding drug use and particularly addiction to mind-altering substances as a disease is another dominant model found within US society and its social institutions. The idea of considering substance use a disease is at least 200 years old. Researching the history of the disease concept of addiction, sociologist Harry Levine (1978) found that habitual drinking during the eighteenth century was not considered a problematic behavior. The emergence of the temperance movement in the nineteenth century shifted American thought toward understanding addiction as a progressive disease. In this idea of disease, a person loses their will to control the consumption of a substance. In the 1940s, the National Council of Alcoholism was founded by E.M. Jellinek, a professor of applied physiology at Yale. The purpose of this council was to popularize the disease model of addiction by putting it on scientific footing by conducting research studies on drug use. Science promoted the disease model. It did not create it (Reinarman 2005).

The disease model of addiction also involves the use of pharmaceuticals, such as methadone, to treat physical and psychological dependence on opiates. Physicians Vincent Dole and Marie Nyswander successfully researched the use of methadone to stabilize a group of 22 patients previously addicted to heroin. Dole and Nyswander (1965) found that with the medication and a comprehensive program of rehabilitation, the patients showed marked improvements. They returned to school, obtained jobs, and reconnected with their families. The researchers found that the medication produced no euphoria or sedation and removed opiate withdrawal symptoms.

The legitimacy of the disease model of addiction was reinforced by the clinical research findings of Dole and Nyswander, which showed that a pharmaceutical (i.e., methadone) could be used to treat addiction. Dole and Nyswander (1965) wrote: “Maintenance of patients with methadone is no more difficult than maintaining diabetics with oral hypoglycemic agents, and in both cases, the patient should be able to live a normal life.” Those who support the disease model of addiction often compare addiction to diabetes. The analogy demonstrates the similarity of addiction to other diseases.

Since the 1990s, addiction has been understood as a neurobiological disease and referred to as a chronic relapsing brain disease or disorder. Using brain imaging technology, scientists and researchers came to find that addictive long-term use of substances changed the structure and function of the brain and had long-lasting neurological and biological effects.

Social scientists have questioned the sole use of the disease model to understand addiction, asserting that addiction also involves a social component. They point out that the disease of addiction is not diagnosed through brain scans. Rather, it is often identified when one is breaking cultural and social norms around productivity and compulsion (Kaye 2012).

11.4.3 Public Health Perspective

A public health perspective toward substance use incorporates a sociological understanding of drug use but focuses on maintaining the health of people who use drugs. Often this approach is labeled harm reduction. Harm reduction is a set of practical strategies and ideas aimed at reducing negative consequences associated with drug use (Harm Reduction Principles N.d.). Harm reduction is also a movement for social justice built on a belief in, and respect for, the rights of people who use drugs. It focuses on providing people who use drugs with the information and material tools to reduce their risks while using drugs. This perspective focuses on reducing the harm of substance use rather than requiring abstinence from all drug use. Similar harm reduction strategies are wearing seat belts or providing adolescents with condoms.

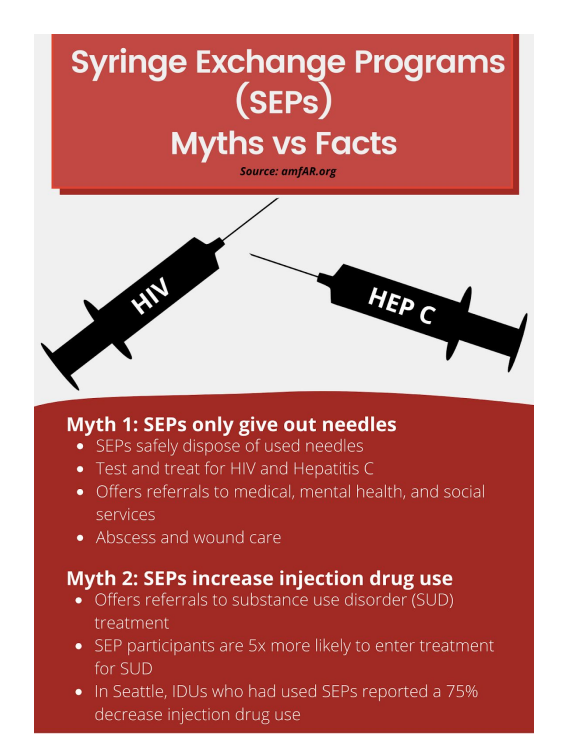

Figure 11.14. In this infographic, we see myths about syringe exchange programs and the facts that dispel the myths.Syringe exchange programs reduce harm. Image description

One of the most well-known harm reduction practices is syringe exchange. This became legal during the HIV epidemic of the 1980s and ’90s to help people who inject drugs avoid infection with the then-deadly virus. Currently, harm reduction is also associated with the distribution of the opioid overdose reversal antidote—Narcan or Naloxone. This harmless medication can almost instantaneously reverse an opioid overdose, saving a person’s life.

The public health or harm-reduction perspective toward drug use can be controversial because some believe that it enables drug use. There is no scientific evidence to support this idea. Instead, scientific evidence shows that syringe exchange reduces HIV and hepatitis C rates, and the distribution of Narcan lowers drug overdose mortality rates (Platt et al. 2018; Fernandes et al. 2017; Chimbar & Moleta 2018).

11.4.4 Sociological Model

The sociological model of drug use and addiction examines how social structures, institutions, and phenomena may lead individuals to use mind-altering substances to cope with difficulty and distress. A sociological view also examines how social inequalities can make the impacts of drug use worse for some social groups than others.

Within the sociological model, a sociopharmacological approach looks at how social, economic, and health policy might exacerbate harm to people using substances. Sociopharmacology is a sociological theory of drug use developed by long-time drug use researcher Samuel R. Friedman. Friedman (2002) writes that approaches toward understanding drug use that focus on the psychological traits of the people using the drugs and the chemical traits of the drugs ignore socioeconomic and other social issues that make individuals, neighborhoods, and population groups vulnerable to harmful drug use.

To consider how the sociopharmacological approach plays out in everyday life, consider how drug policy prohibits the use of heroin and results in several harmful effects. New syringes can be hard to find. People will inject in unclean and rushed circumstances, which may negatively impact their health by putting them at risk of contracting HIV or life-threatening bacterial infections.

This type of analysis is also thought of using the analytic concept of risk environments developed by Tim Rhodes. A risk environment is a social or physical space where a variety of things interact to increase the chances of drug-related harm (Rhodes 2002). An analysis of risk environment looks at how the relationship between the individual and the environment impacts the production or reduction of drug harms .

In his sociopharmacology theory, Friedman also notes that the social order might cause misery for some social groups, which might cause people to self-medicate with drugs. People who experience class, gender, or racial oppression suffer harm. As a way to deal with that harm, they may choose to self-medicate with drugs or alcohol.

For example, working a low-paying service job where you deal with unhappy customers and mistreatment from your boss may lead you to blow off steam by using substances. Individualistic theories of drug use stigmatize and demonize individuals who use drugs as being weak or criminal. According to the sociopharmacological approach, if anything should be demonized, it should be the social order—not the individual who uses drugs (Friedman 2002).

Looking at the social determinants of the opioid crisis provides a way to discuss a sociological approach to studying drug use. Many approaches to understanding the opioid crisis focus on the supply of opioids in the US and whether they were pharmaceutical or illicit. This approach misunderstands the reasons individuals use opioids. The label deaths of despair has been used to describe three types of mortality that are on the rise in the US. Deaths of despair have caused a decline in the average lifespan among Americans. These three deaths occur from drug overdose, alcohol-related disease, and suicide. Death from these conditions has risen sharply since 1999, especially among middle-aged White people without a college degree (Dasgupta, Beletsky, and Ciccarone 2018).

Figure 11.15. “Deaths of despair” are surging in white America [YouTube]. Economists Anne Case and Sir Angus Deaton explain their research on the opioid crisis and deaths of despair in this 3:47-minute video. As you watch, please pay attention to the social forces that influence this social problem. Transcript

Researchers are examining how economic opportunities impact opioid use and overdose rates. In a study focused on the Midwest, Appalachia, and New England, areas that are predominantly White, researchers found that mortality rates from deaths of despair increased as county economic distress worsened. In rural counties with higher overdose rates, economic struggle was found to be more associated with overdose than opioid supply (Monnat 2019).

Analysis of the social and economic determinants of the opioid crisis notes that the jobs available in poor communities, which are often in manufacturing or service, present physical hazards and cause long-term wear and tear on the worker’s body (Dasgupta et al. 2018). An on-the-job injury can lead to chronic pain, which may disable a person. The disability may cause them to seek pain relief through opioids. The resulting addiction pushes them into poverty and despair. The video in Figure 11.15 describes the trends in the deaths of despair.

A 2017 report from the National Academy of Sciences used a sociological view of drug use when it commented on the cause of the opioid crisis. The report states:

Overprescribing was not the sole cause of the problem. While increased opioid prescribing for chronic pain has been a vector of the opioid epidemic, researchers agree that such structural factors as lack of economic opportunity, poor working conditions, and eroded social capital in depressed communities, accompanied by hopelessness and despair, are root causes of the misuse of opioids and other substances. (Zoorob and Salemi 2017)

However, this research into deaths of despair focused on the increased opioid-related deaths due to overprescription in the first wave of the opioid crisis. Although the researchers don’t name it specifically, they were looking at patterns of drug use and abuse by White people. The researchers demonstrate implicit bias.

As the crisis continues, researchers are examining the impact of the second and third waves of the crisis. According to a study from Marjorie C. Gondré-Lewis, Tomilowo Abijo, and Timothy A. Gondré-Lewis:

Categorically, from 2015 to 2017, African Americans experienced the highest OOD increase of all races analyzed; 103% for opiates and 361% for synthetic opioids in large central metropolitan cities, and respectively 100% and 332% in large fringe metros Illicitly manufactured fentanyl accounts for increased overdose deaths more than any other opioid across the USA. (2022)

The opioid crisis is now impacting urban, Black people disproportionately.

Despite the research biases we notice here, a sociological view of drug use helps us to understand the social contexts that can lead to drug use and cause it to be harmful or deadly. Without a sociological analysis, we’d only be looking at individual people and drugs. We would miss the entire social environment which influences both drug use and the consequences of drug use. A sociological analysis notices widespread social structural elements that might increase drug use: racism, economic despair, and hopelessness. This analysis can help us create policies and programs that can be beneficial for large numbers of people. From the sociological perspective, we see that, like other social problems, differences in social location create unequal outcomes.

11.4.5 Intersectional Model: Colonization and Drug Use

Indigenous people report the second highest rate of illicit drug use disorder between 2015 and 2019, at 4.8 percent. The highest percentage is among people who identify as two or more races or ethnicities. Indigenous people are also the highest percentage of people who sought treatment for illicit drug use disorders and received it (Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality 2021).

Figure 11.16. Researcher Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart of the Hunkpapa/Oglala Lakota examines drug use. How does her work explore generational trauma you might remember from the ACEs model in Chapter 10?

The work of researcher and professor Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart, shown in Figure 11.16, explains how the historically-based trauma experienced by Indigenous communities in the United States may impact substance use. She emphasizes that the traumatic losses suffered across generations by the North American Indigenous populations meet the definition of genocide. She lists massive traumatic group experiences as part of the intergenerational trauma experienced by this community, which may contribute to substance use (2003:8).

This list includes traumas such as massacres; prisoner of war experiences; starvation; displacement; separation of children from families and placement in compulsory and often abusive boarding schools; disease epidemics; forced assimilation; and the loss of language, culture, spirituality. All of this contributes to the breakdown of family kinship networks.

Brave Heart points to an 1881 US policy outlawing the practice of Native ceremonies, which prohibited traditional mourning practices. This undermined practices of healing and resolution that might improve wellness and potentially lower problematic substance use levels. Urban Indigenous people who use alcohol and/or other illicit substances reported symptoms of historical trauma (Wiechelt et al. 2012). Brave Heart (2003) points out that alcohol was not part of Indigenous culture except for in specific ceremonies before colonial contact. If you’d like to listen to Brave Heart herself, watch Historical Trauma in Native American Populations [Video].

Researchers suggest that treatments for substance use disorder among Indigenous peoples should coincide with decolonizing practices. This means that Indigenous communities should be supported in making attempts and achieving control of land and services. Nutton and Fast report that:

…communities that have made attempts to regain control of land and services have been found to have lower suicide rates, reduced reliance on social assistance, reduced unemployment, the emergence of diverse and viable economic enterprises on reservation lands, more effective management of social services and programs, including language and cultural components, and improved management of natural resources. (2015:842)

Identity formation can also be a helpful part of drug treatment for Indigenous individuals. Research indicates that increased participation of Indigenous peoples in their culture of origin can decrease the prevalence of substance use disorder. (Nutton & Fast 2015)

Finally, all drug treatment interventions should be culturally adapted for Indigenous communities. For example, among Indigenous people inhabiting the Great Plains, the Sun Dance was performed in thanksgiving for a bountiful year and a request for another year of food, health, and success. Today community members pledge to do the Sun Dance to maintain their sobriety from alcohol or drugs.

11.4.6 Licenses and Attributions for Five Models of Addiction

Open Content, Original

“Five Models of Addiction” by Kelly Szott is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Intersectional Model: Colonization and Drug Use, Sun Dance Content” is

adapted from “Native Peoples of North America,” by Susan Stebbins, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications: Lightly edited for clarity.

Figure 11.12. “Drug Schedule” from “Legal Foundations and National Guidelines for Safe Medication Administration,” by Open Resources for Nursing (Open RN), Nursing Pharmacology is licensed under CC-BY 4.0.

Figure 11.13. “The Drunkard’s Progress Lithograph” by Nathaniel Currier is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 11.14. “Syringe Exchange Programs (SEP) Myths vs. Facts” from “Syringe Exchange Toolkit” by AIDS Advocacy Network, American Medical Students Association is included under fair use.

Figure 11.15. “Deaths of Despair Are Surging’ in White America” by Brookings Institution is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 11.16. “Photo of Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart” is all rights reserved and included with permission.