12.3 Social Location and Mental Health

Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman

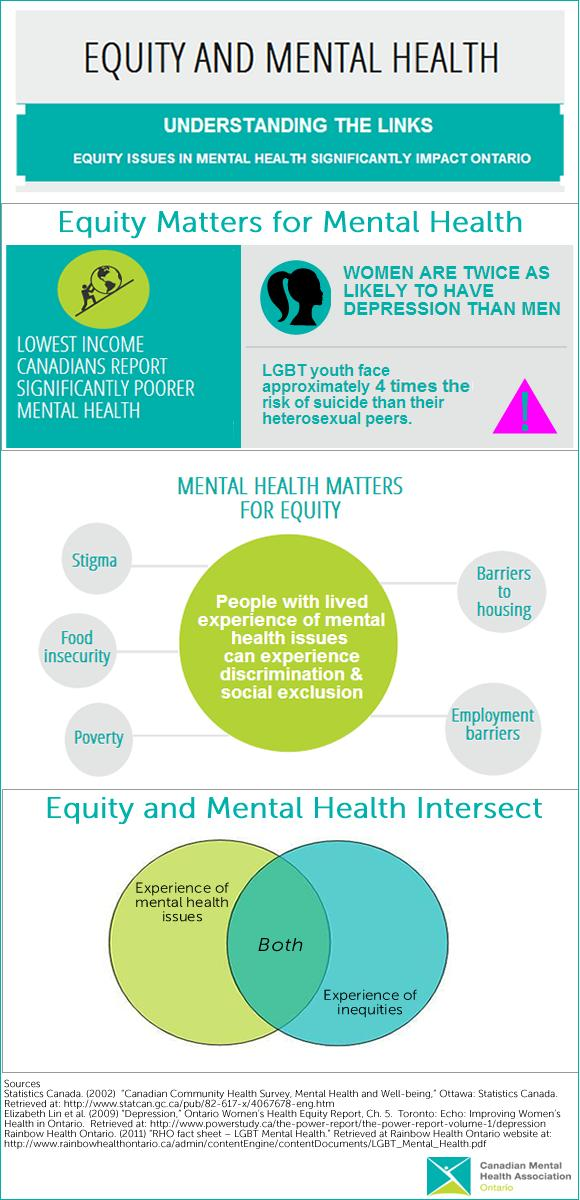

Figure 12.9. Equity Matters to Mental Health: Equity and Mental Health impact each other. How does this infographic help us to understand this? Image Description

The infographic in Figure 12.9, Equity Matters to Mental Health, highlights the intersectional nature of social location and mental health. In the related report, the Canadian Mental Health Association-Ontario describes the relationship between equity, mental health, and intersectionality:

- Equity matters for mental health. Due to decreased access to the social determinants of health, inequities negatively impact the mental health of people who live in Ontario. Marginalized groups are more likely to experience poor mental health. In addition, marginalized groups have decreased access to the social determinants of health essential to recovery and positive mental health.

- Mental health matters for equity. Poor mental health has a negative impact on equity. While mental health is a key resource for accessing the social determinants of health, historical and ongoing stigma has resulted in discrimination and social exclusion of people with lived experience of mental health issues or conditions.

- Equity and mental health intersect. People often experience both mental health issues and additional inequities (such as poverty, racialization, or homophobia) simultaneously. Intersectionality creates unique experiences of inequity and mental health that pose added challenges at the individual, community, and health systems level (Canadian Mental Health Association 2014).

Mental health status itself can influence your ability to stay in school, hold a job, or raise a family. And the reverse is also true—if you are struggling to put food on the table, keep your kids stable, or stay safe in your neighborhood, you are more likely to have poor mental health.

Although there are many ways to layer social location, we will look more deeply at race and ethnicity, class, language, and gender.

12.3.1 Race and Ethnicity

Figure 12.10. #TerpsTalk: Intersection of Race and Mental Health [YouTube]. Please watch the first 8 minutes of this video discussing both the needs for mental health services and the barriers to services for People of Color. What issues are new as part of our discussion of social problems? Transcript

The video in Figure 12.10, “The Intersection of Race and Mental Health,” presents some of the newest research on race and mental health. It specifically calls out racial trauma as a cause of mental health issues. Racial trauma is one term used to describe the physical and psychological symptoms that People of Color often experience after being exposed to stressful experiences of racism (Jernigan et al. N.d.). People of Color experience discrimination in the form of microaggressions, which we discussed in Chapter 2. We discussed the police violence and disproportionate incarceration of People of Color in Chapter 11. These experiences, and many others, contribute to racial trauma.

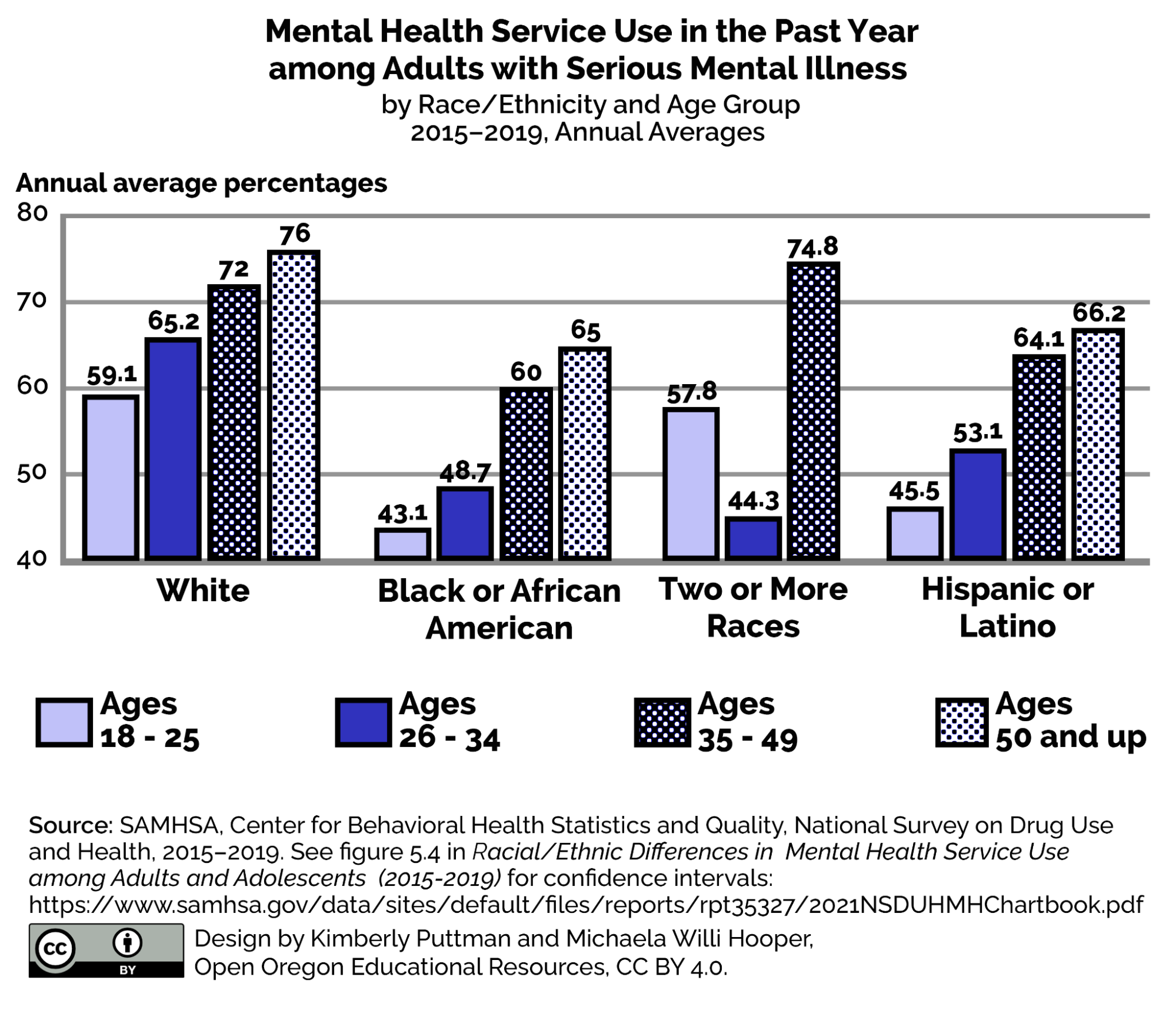

Making this problem worse, Black, Brown, and Indigenous people have less access to mental health services than White people. In the chart in Figure 12.11, we notice that White people use mental health services more than any other group.

Figure 12.11. Mental Health Service Use in the Past Year among Adults with Serious Mental Illness, by Race/Ethnicity and Age Group: 2015–2019, Annual Averages. Image Description

We can also examine the amount of unmet needs for mental health services according to race and ethnicity. When we do this, we see that People of Color have more unmet needs than non-Hispanic White people.

Black and Brown people have a harder time accessing quality mental health services. When they do receive services, they are more likely to have a negative experience. Some cultures have more stigma around mental health issues than White Americans generally have. This can be a barrier for some immigrants and first- and second-generation Americans to seek services.

For immigrants, mental health providers often lack language and cultural competency skills, which makes the treatment much less effective. Finally People of Color are profoundly underrepresented in research and clinical trials for new treatments. Mental health researchers often don’t consider the unique experiences of People of Color when they develop new treatment options or medications.

12.3.2 Class Issues in Mental Health Treatment

One of the most consistent findings across studies is that lower socioeconomic groups have greater amounts of mental illness. Why is this the case?

One of the earliest studies of the sociology of mental health came from the University of Chicago in the 1930s. You may remember this school from our discussion of Jane Addams in Chapter 1. Sociologists explored whether mental illness caused poverty or whether poverty caused mental illness. The two researchers who led this project—Faris & Dunham—looked at psychiatric admissions to Chicago hospitals by neighborhood. What they found was rather shocking—there was a nine times increased rate of schizophrenia from people who came from poorer neighborhoods, than from more middle-class neighborhoods. The researchers tried to figure out why.

One idea was social selection, the idea that lower class position is a consequence of mental illness. Mentally ill people would drift downward into lower income groups or poorer neighborhoods because they couldn’t keep jobs. In addition to considering social selection, they considered social causation, also. In this model, which Faris & Dunham later refuted, lower class position was a cause of mental illness.

Results of this early study came back mixed. At first, Faris & Dunham said that the isolation and poverty of living in the central city created schizophrenia—cause. But then, they changed their minds and said people with schizophrenia have downward drift and moved to the central, poorer part of town after developing schizophrenia—effect. Later studies have found that Faris & Dunham’s study was actually trying to tell us that it’s both—cause and effect. Social selection theories and social causation theories can be used to account for the relationship between schizophrenia and poverty.

As our infographic on equity and mental health (Figure 12.9) shows, people with mental health issues can struggle with educational and economic stability because sufficient social supports are not in place to support them. Poverty itself can be a risk factor for poor mental health. This optional article from the Guardian, Mental Illness and Poverty: You Can’t Tackle One Without The Other might help you to make more sense of this complex relationship.

12.3.3 Gender

Figure 12.12. Teen Intersectionality Series: Mental Health & Gender [YouTube]. As you watch this 4-minute video, please consider how gender identity and sexual orientation might impact mental health and well-being. Transcript

Gender has often been an explanation for the occurrence of mental health and mental illness. While traditional explanations focus on women, as explored in the previous section, newer research is focusing on the interactions of nonbinary and gender fluid folx (a deliberately non-binary word) and their mental health. The video in Figure 12.12 provides some detail about this experience.

But why is gender such a persistent variable in all of our social problems? To make sense of this, let’s explore the social structure of patriarchy more carefully in the next section.

12.3.4 Unpacking Oppression, Embodying Justice: Patriarchy

Figure 12.13. Gender Fluid Person: People do gender in a variety of ways. Would you identify this person as male, female, fluid, androgynous, or none of the above?

As early as Chapter 2, we started using the word gender in this book. We discussed sexual orientation and gender identity in Chapter 7, but as usual, we have more to say. Traditionally, sociologists defined gender as the attitudes, behaviors, norms, and roles that a society or culture associated with an individual’s biological sex. Gender describes the social differences between female and male or the meanings attached to being feminine or masculine. This definition is somewhat outdated because it labels gender as only female or male rather than seeing gender expression and gender identity as a continuum.

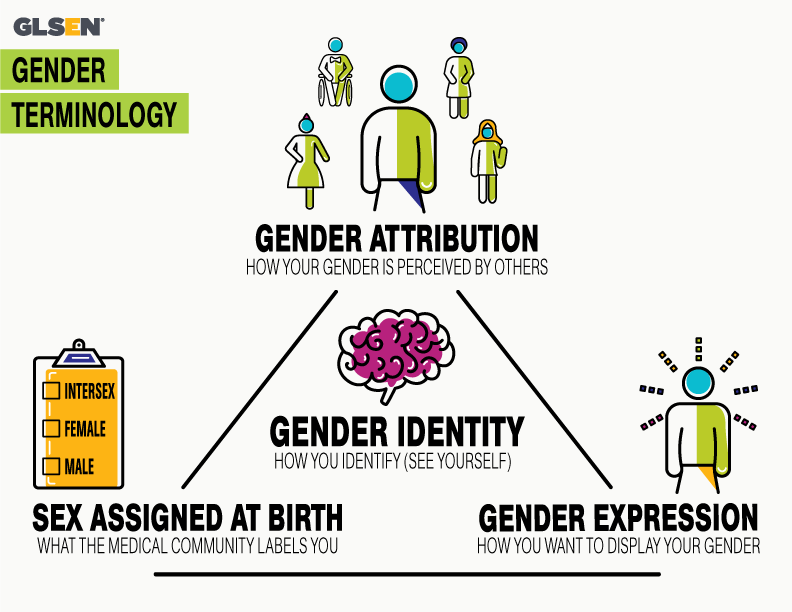

Figure 12.14. This diagram from GLSEN shows the relationship between sex and gender and the different ways gender identity interacts with gender expression and attribution. Why might it be useful to have different layers of gender? Image description

More new words, you say? The Human Rights Campaign Foundation (HRC) defines gender identity as one’s innermost concept of self as male, female, or a blend of both or neither—how individuals perceive themselves and what they call themselves (Human Rights Campaign 2023). One’s gender identity can be the same or different from their sex assigned at birth. For example, you may know yourself as female, even if your physical body has a penis. Alternatively, you may feel like female or male gender labels don’t fit you at all.

HRC further defines gender expression as the external appearance of one’s gender identity, usually expressed through behavior, clothing, body characteristics, or voice, and which may or may not conform to socially defined behaviors and characteristics typically associated with being either masculine or feminine (Human Rights Campaign 2023). Often, your identity and your expression match. Sometimes, you may choose to wear skirts, glitter, and paint your nails, even if your gender identity is male.

Gender, then, is a complex construct. Gender develops throughout life. We may change our gender identity as we age. If this concept challenges you, you may want to watch Paula Stone Willams, a transgender woman, describing what she learned about being male and being female in her TED talk I’ve lived as a man and a woman .

How sociologists understand gender changes as we listen carefully to people who don’t fit in traditional gender boxes. How each of us “does” gender changes as we become more authentically ourselves throughout our lives.

Even though our concept of gender is fluid, our social structures consistently privilege people with a male gender and marginalize people of a female or nonbinary gender. How can we explain the persistence of this oppression?

Figure 12.15. Alda Facio is a Costa Rican jurist, writer, teacher and activist. How might you re-write her definition of patriarchy?

Like our concepts of structural racism in Chapter 3, our society supports the structure of patriarchy. Alda Facio, a Costa Rican jurist, writer, teacher, and activist, offers the following definition of patriarchy:

Patriarchy is a form of mental, social, spiritual, economic and political organization/structuring of society produced by the gradual institutionalization of sexbased political relations created, maintained and reinforced by different institutions linked closely together to achieve consensus on the lesser value of women and their roles.

This is a powerful definition, but it is complicated to understand. Think of it this way. Put simply, feminism is the radical idea that women are people. Patriarchy is the social structure and related behaviors that give men power, and oppression women and people of non-traditional gender. As social problems scholars, we want to understand how patriarchy works in a much deeper way.

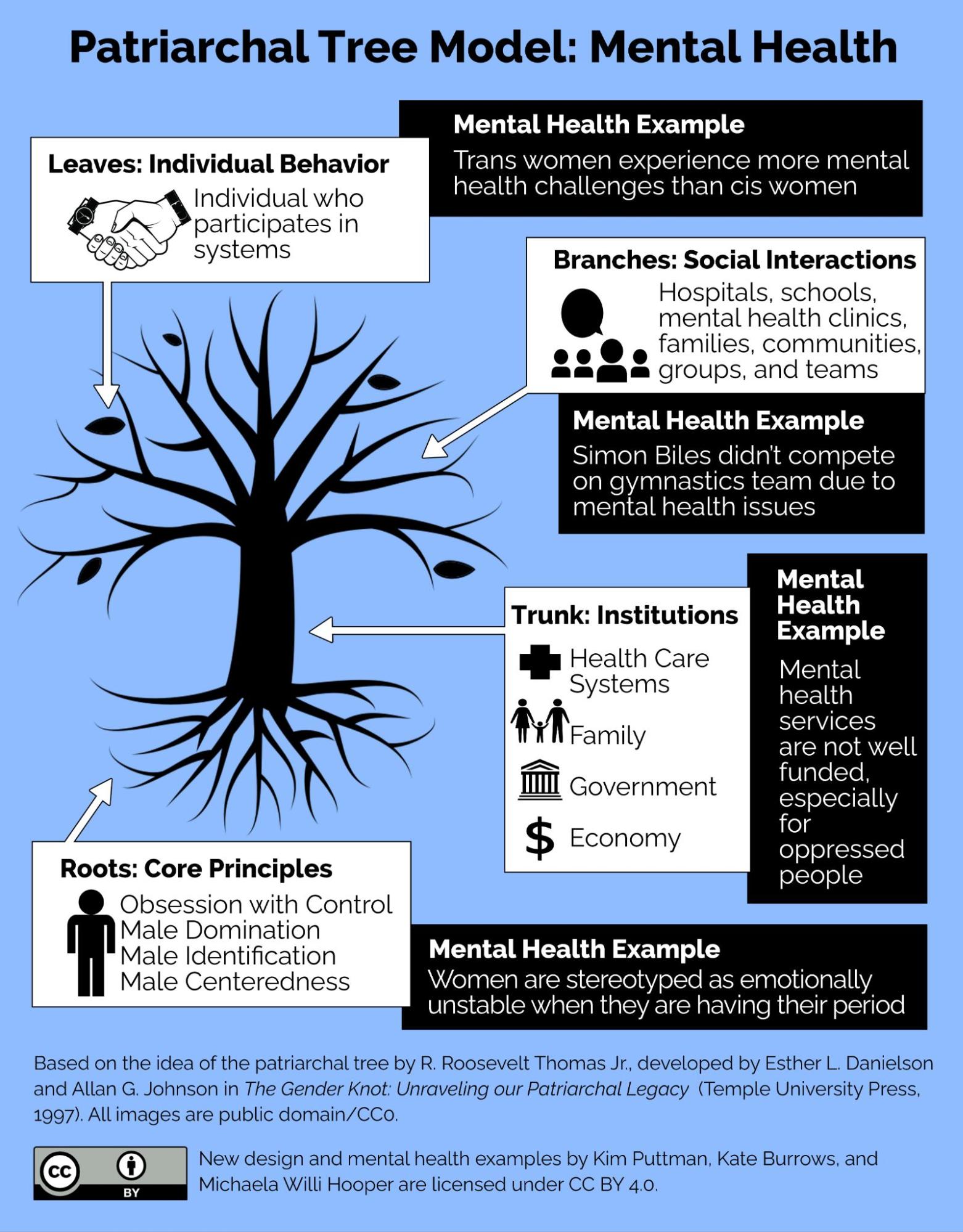

Figure 12.16. Patriarchy is like a tree. It has the roots of core principles, the trunk of institutions, the branches of social interactions and the leaves of individual behavior. Where do you think individual and collective action needs to happen to change this system? Image description

In the drawing of this tree, we notice:

Roots: The roots of the patriarchal tree are the core beliefs and practices that provide an often unconscious base of patriarchy. These underlying principles are obsession with control—controlling women’s bodies, money, and choices. This principle also supports the idea that men should stay in control—of their emotions, lives, and other people’s lives. The second principle, male domination, locates men in positions of authority. Leadership is a male role and a source of male power. The third principle, male identification, locates men at the center of what is right and good. We see this principle in action when we use words like all mankind when we actually mean all people. The fourth and final principle is male centeredness. In this principle, we focus on and value the activities of men and boys, rather than women, girls, and nonbinary gendered people. Combining many of these principles in action, the US Soccer Federation only agreed that female and male soccer players should earn equal pay in 2022. For more on this landmark victory, feel free to read The US National Women’s Soccer Team wins $24 million in equal pay settlement.

Trunk: The trunk of this structural inequality are our institutions, our governments, and our economy. Throughout this book, we have seen examples of gender inequality, often supported by our schools, businesses, and governments. We’ve also seen how these organizations sometimes change to become less patriarchal.

Branches: The branches of our tree are the smaller containers of social interaction, such as families, churches, clubs, work teams, or your favorite gamer’s discord group. At this level, group norms influence the behavior of individuals. In these smaller communities, we explore what it means to do the gender of nonbinary, female, or male. For example, in many heterosexual dual-parent families, members take on traditional gender roles.The father does the outside chores like mowing the lawn, the mother cooks, and the kids do their homework with the help of both their parents.

Leaves: Each of us is a leaf on the patriarchal tree. In our own actions, we can reinforce gender norms, or we can consciously choose to uproot these deep roots. Our choices matter deeply. However, by placing each of us in a system of power, we move away from shame, blame, and a bad person model. Instead, we can examine how social structures of gendered oppression may be reproduced in our own daily interactions. This knowledge empowers us to choose differently.

Because this structure is both deeply rooted and interconnected, it is resistant to change. Also, patriarchy itself becomes a reason for inequality in all of our social problems.

Now it’s your turn to unpack oppression and embody justice

Patriarchy exists as roots, trunk, branches, and leaves.

Find an example of patriarchy at work in the world. This could be a law, policy, practice, story, image, song, personal experience or other kinds of example.

What level of patriarchy is being employed here?

Where do you see the other three levels of patriarchy supporting this example?

What would it take to end patriarchal oppression?

12.3.5 Licenses and Attributions for Social Location and Mental Health

Open Content, Original

“Social Location and Mental Health” by Kathryn Burrows and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 12.11. “Mental Health Service Use in the Past Year among Adults with Serious Mental Illness by Race/Ethnicity and Age Group” by Kimberly Puttman and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Data source: National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 2015–2019, SAMHSA, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality.

Figure 12.16. “Patriarchal Tree Model: Mental Health” by Kimberly Puttman, Kathryn Burrows, and Michaela Willi Hooper is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Based on the idea of the patriarchal tree by R. Roosevelt Thomas Jr., developed by Esther L. Danielson and Allan G. Johnson in The Gender Knot: Unraveling our Patriarchal Legacy (Temple University Press, 1997). All icons are public domain/CC0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 12.13. “Photo of Gender Fluid Person” by Mapbox is licensed under the Unsplash License.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 12.9. “Equity Matters to Mental Health” © the Canadian Mental Health Association is all rights reserved and used with permission.

Figure 12.10. “#TERPSTALK: Intersection of Race and Mental Health” by Maryland Athletics is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 12.12. “Teen Intersectionality Series: Mental Health & Gender” by Gender Spectrum is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 12.14. “Gender Terminology Diagram” by GLSEN is included under fair use.

Figure 12.15. “Photo of Alda Facio” by Women’s Human Rights Institute is included under fair use.