13.2 Death and Dying as a Social Problem

Patricia Antoine and Kimberly Puttman

“Nothing is certain but death and taxes.” This phrase summarizes some of the wisdom of living in a modern economy. If we think back to the sociological imagination from Chapter 1, we know that of course, death is personal. It happens to each of us in a unique and individual way. However, death is also a social event. Our families, friends, and communities walk through the process with us. We depend on the social institutions of hospitals and hospices and the businesses of mortuaries and funeral homes to care for us. Even the government must issue death certificates for deaths to be considered valid. In this sense, death is also a social problem. Let’s look at why that is, using the characteristics of a social problem from Chapter 1.

13.2.1 Beyond the Experience of the Individual

Death is one of the most intimate and personal issues a person will ever confront. What happens to an individual is affected by the social context within which it takes place, but death also has broader social implications.

At a micro level of analysis, death and the dying process involves the loss of social roles and a shift in existing roles. For instance, when a parent dies, you lose someone in the parental role. Older siblings, grandparents, or family friends may need to step in and take on parenting responsibilities. Social relationships are also altered. The loss of a member of our social circle affects all who are part of that social network. As a result of a death, the group dynamics and relationships may need to be renegotiated and a new shared meaning developed.

At a social institutional level, death and the resulting loss of a worker, a teacher, or a community leader affects institutional processes and a shift of institutional resources to fill vacated roles. While a single death may have one type of impact, numerous deaths may have a more immediate and significant societal impact. As we discussed in Chapter 1, the COVID-19-related workforce issues disrupted the flow of goods and services worldwide.

13.2.2 Conflict in Values: Right To Die

Figure 13.4. This 9.27-minute video, Right-to-die movement finds new life beyond Oregon [YouTube], discusses the right to die. As you watch the first 5 minutes, you can think about who is making the decision about when to die. Also, what conflict in values is present as we answer this question? Transcript

All human societies have to answer the profound questions of who lives and who dies. We discussed the conflict in values related to who lives when we discussed reproductive justice in Chapter 10. We also see a conflict in values in talking about who dies.

Who gets to decide who dies? What criteria or values do people use in order to make this decision? This conflict in values is expressed in right to die laws. These right to die laws are the laws that allow a person who suffers from a terminal disease and meets the required criteria to choose to end their life on their terms. They provide an option for eligible individuals to legally request and obtain medications from a physician to end their life in a peaceful, humane, and dignified manner. As of 2023, only 10 states and the District of Columbia have a Death with Dignity law.

In recent decades there has been a growing movement to ensure that individuals have the autonomy and agency to control their own end-of-life decisions, including the right to die. The government, with the advice of medical professionals, sets standards, accepted practices, and legal statutes concerning end-of-life options. These regulations and standards may conflict with the personal preferences of those who are in the dying process.

This highlights a fundamental question, “Who has the ultimate right to decide how and when an individual’s life ends?” Those working for the passage of so-called “right-to-die” legislation (also referred to as physician-assisted suicide or physician-assisted death) assert that individuals should be able to make the decision as to how much pain, suffering, and debilitating symptoms at end-of-life they should endure.

The first right-to-die law in the United States was enacted in Oregon in 1997. Oregon’s Death with Dignity Act (DWDA) allows a terminally ill individual to end their own life with a self-administered lethal dose of medication prescribed by a physician for that purpose (Oregon Health Authority 2022). The Oregon law sets out a very structured procedure with specific requirements and criteria that must be met for an individual to utilize this option. Generally, you have to be able to make decisions for yourself, and two physicians must agree. If you would like to learn more about these criteria, look at the Frequently Asked Questions about Death With Dignity [Website]

Those who oppose this type of legislation express fear over a lack of oversight at the moment of death. They cite concerns that the final decision to end one’s own life will be made by others on behalf of those who may be too ill to speak on their own behalf. Some fear the normalization of physician-assisted death to the point that patients will feel responsible for relieving the burden their care places on their loved ones. And many believe it is the job of physicians to alleviate suffering, not the role of the patient to decide.

Beliefs grounded in a sanctity of life orientation strongly emphasize the basic duty to preserve life. This perspective is often grounded in cultural and religious tenets that explain life as being a sacred gift granted to humans accompanied by a requisite responsibility to care for the body. Such an orientation may lead to a preference for using all available medical options to live as long as possible.

Alternatively, others may focus more on the quality of a person’s life. A quality of life perspective argues that when life is no longer meaningful, the obligation to preserve life no longer exists. Although medical technology may be able to extend life, the human experience of living is more important than simply keeping the body medically functioning. From this orientation toward life, the emphasis is placed on the ability to live with dignity and purpose. Decisions concerning the use of end-of-life medical interventions are shaped by the intentional consideration of the distinction between the quantity of life and the quality of that life.

Where do you stand?

13.2.3 Inequality in Life Expectancy

Although death is an inevitability of the human condition, mortality rates vary based on social location. When and how a person dies is more than just the outcome of individual genetics and human physiology. Life expectancy and cause of death are also affected by the social determinants of health that we talked about in Chapter 10, such as access to healthcare, quality of life indicators, geographic location, and socioeconomic variables. Differential patterns in life expectancy and death rates based on gender and race/ethnicity are affected by broader social issues and systemic inequalities.

Social institutional features involving work, family, social class, healthcare, and social construction of gender role expectations contribute to the ongoing differential life expectancy, the number of years a person can expect to live, based on an estimate of the average age that members of a particular population group will be when they die (Ortiz-Ospina 2017). When we look at life expectancy based on gender, we see a difference. Males are predicted to live only 76.3 years on average, while females are expected to live 81.4 years on average (National Center for Health Statistics 2021).

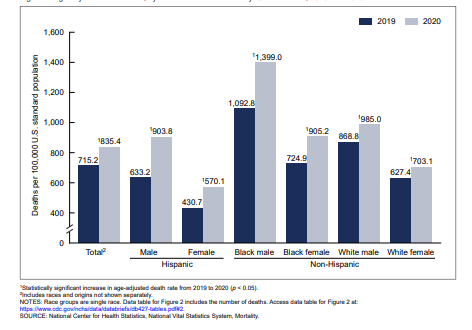

Comparative death rates based on race and ethnicity also reflect systemic inequalities in social systems and people’s social experiences (Figure 13.5).

Figure 13.5. Age-Adjusted Death Rates by Sex and by Race/Ethnicity United States 2019 and 2020. Black males experience the highest rate of death. Part of the difference in rates of death in 2020 was due to COVID-19. Image description

The impact of social inequalities is also evident during significant catastrophic events that challenge society, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. With the emergence of a new virus, this medical crisis strained social institutions and fundamentally interrupted previous patterns of social activity. Any one of us could get COVID-19, but the probability of contracting the virus and the likelihood of death from the infection are affected by social factors. Many of these social risk factors disproportionately impact people based on social location indicators such as race, ethnicity, and social class.

All Cases and Deaths by Race and Ethnicity Among Ages 18+ in California, as of May 9, 2023

|

Race/ Ethnicity |

Number of cases |

Percent of cases |

Number of deaths |

Percent of deaths |

Percent of CA population |

|

Latino |

3,171,021 |

42.5 |

42,360 |

41.9 |

36.3 |

|

White |

2,042,907 |

27.4 |

36,630 |

36.2 |

38.8 |

|

Asian |

816,262 |

11.0 |

11,391 |

11.3 |

16.2 |

|

African American |

420,445 |

5.6 |

7,138 |

7.1 |

6.1 |

|

Multi-Race |

72,825 |

1.0 |

1,715 |

1.7 |

1.7 |

|

American Indian or Alaska Native |

34,503 |

0.5 |

478 |

0.5 |

0.5 |

|

Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander |

58,685 |

0.8 |

593 |

0.6 |

0.3 |

|

Other |

837,322 |

11.2 |

907 |

0.9 |

0 |

|

Total with data |

7,453,970 |

100.0 |

101,212 |

100 |

100 |

Figure 13.6. This chart shows the number of COVID-19 cases and deaths by race and ethnicity in California as of May 9, 2023. Although some of the reported cases and deaths don’t have race and ethnicity associated with them, the trends are clear. If race and ethnicity had no impact on who was more likely to die, the percentage of California’s population and the percentage of deaths would match. They don’t.

As you look at this chart, you may want to start at the last column. This column reflects the percent of California’s total population for a particular group’s race and ethnicity. If race and ethnicity did not influence the rate of catching COVID-19 or dying from COVID-19, you would expect that columns Cases (column 2) and Deaths (column 4) would match the last column. They do not. Instead, we see that White, Asian, and multi-ethnic people have a slightly lower-than-expected death rate. People of all other races and ethnicities have a slightly higher death rate. When you consider what you learned in Chapter 10 about why this is true for health, you can apply those learnings to understanding the consequences of social location on death.

13.2.4 The Social Construction of Death

Determining when a death takes place seems straightforward and obvious. When a person’s body ceases to function, death has occurred. But as one delves deeper into the details and specifics, that task becomes far more complex. Historically, there have long been accounts of people who were determined to be dead when, in fact, they were still very much alive. Although not common, such instances were often a result of shallow breathing or faint heartbeats that went undetected. Advancements in medical technology address this possible problem. At the same time, they introduce new challenges in determining when death occurs. Modern medicine’s ability to artificially keep people alive raises new and difficult questions in determining when death occurs. Therefore, society found a need to clearly define what determines death, delineate the criteria to be used to establish that death has occurred, and develop a process to socially recognize and certify death.

Clinical Death

The customary method of determining death has centered on the cessation of basic vital signs of life – the absence of breathing and a heartbeat. However, advancements in new technology have raised new issues and challenges in using these conventional methods for establishing death. The use of advanced life support systems, such as ventilators, respirators, and various methods of cardio-pulmonary support, can now artificially support life for long periods of time. In these cases, a person can be kept “alive” through mechanical means for days, months, and in some cases, years. While in this state, do we say that the person is alive, or that the person is dead?

With the ability to keep a person breathing and the heart beating through artificial means for long periods of time, the medical community turned to the concept of brain death to determine death. Based on the work of the 1968 Harvard Medical School Ad Hoc Committee, brain death, or what became known as the “whole-brain” definition of death, involved the following criteria: the absence of spontaneous muscle movement (including breathing), lack of brain-stem reflexes, the absence of brain activity, and the lack of response to external stimuli. This criterion for brain death is used to augment the customary use of vital signs when they may be ambiguous.

Legal Death

The definition of death affects many aspects of our daily lives. The death of an individual often triggers government laws that regulate issues directly related to how the body of the deceased is handled and the options for the final disposal of the corpse. Issues arising after death may also require some type of official government documentation verifying a death has occurred. A government-issued death certificate with verified information as to the date, place, and in some cases, the cause of death is needed to execute wills and inheritances, file necessary taxes, assess any civil and criminal liabilities, and a host of other legal issues regulated by the government.

With the broad-based acceptance of the medical criteria for death, legislative discussion ensued to develop a standardized, legal means for determining that a death has occurred. Efforts focused on updating the legal standards used to determine death that closely aligned with the criteria being used by the medical community.

Social Death

Social death involves the loss of social identity, loss of social connectedness, and loss associated with the disintegration of the body (Králová 2015). This can be marked by a specific event, such as biological death. But it can also involve a series of changes, such as the loss of the ability to take part in daily activities, the loss of social relationships, and/or the loss of social identity during end-of-life and the dying process. When there is a social determination of death, a person’s place in society changes. There is a shift in their social status that denotes a separation from society and community. Establishing when social death occurs signals others as to the expected adjustments in social interactions.

Social death can change social role expectations, social status, and social interactions. When a person is dying, they may no longer be able to fulfill their social roles. For instance, a mother or father may no longer be able to care for the children. The children may need to become care providers for the parents. Adult children may become the care provider for an aging parent. The meaning of friendship expectations changes, and social interaction within community or work settings are altered or severed.

After biological death, the status transition of the deceased from the world of the living to the spiritual realm or the world of their ancestors is often denoted by funeral rituals. Socio-cultural beliefs, values, and norms form the basis for the determination and meaning of social death. In the US dominant culture, the meaning of social death may be directly linked to the absence of medical/biological indicators such as breathing, heartbeat, brain-based reflexes, and processes that then lead to various funerary rituals.

In other cultural belief systems, biological death is only one aspect of determining social death. For the Toraja people of Indonesia, social death does not come until the body leaves the home. They often keep the body of the biologically deceased in the home as an ongoing social member of the family and community for weeks, months, or even years. During this time, the person is perceived as being sick or in a prolonged sleep. They are fed and bathed, and their clothes are periodically changed. They are talked to, hugged, caressed, and moved to various settings to ensure they are included in family and community activities. The removal of the body from the home and completion of funerary rituals denotes the change in social status and social determination of death (Arora 2023; Seiber 2017).

The video, Here, Living With Dead Bodies for Weeks—Or Years—Is Tradition [YouTube Video], depicts the Torajan view of death. Please be aware that it contains graphic images of dead bodies and the killing of cows. If this will be triggering for you, you can skip this video. If you do decide to watch it, please consider how death can be social as well as biological. How does this experience of death change your expectations about what it means to be dead?

13.2.5 Interdependent Solutions

The final characteristic of a social problem is that it requires both individual agency and collective action to create social justice. When we apply this characteristic to the experience of death and dying, we can change both the individual willingness to talk about death. We can also create communities that collectively support the experience of dying.

Many of us are afraid to even talk about dying. However, this isn’t the only way to approach death. Instead, we can be open to learning about death and talking about it. We can be death positive. Death positive doesn’t mean that we want to die now. Death positivity means that we are open to honest conversations about death and dying. It is the foundation of a social movement that challenges us to reimagine all things tied to death and dying (Lewis 2022).

One of the ways to have individual agency is to have “the conversation.” In this conversation, you can talk to your parents, your children, your partner, or your friends. You can talk about what you want at the end of life, what you think will happen when you die, how you want your funeral to be, or what gives meaning and value to your life. By having these conversations now, you begin to prepare for the end of your life or the end of life for those you care about. If you’d like to get some ideas about why we talk about death, you could watch Talk About Your Death While You’re Still Healthy [Video].

Figure 13.7 a and b. a) Sociologist and Anthropologist Bernard Crettaz created the idea of the Death Cafe. b) Jon Underwood popularized it. Death Cafes have now been held in over 65 countries. Do you think you would ever attend one?

You can also participate in a Death Cafe. A Death Cafe is a social gathering, usually with tea and cake, where people talk about death. The question may range from, “What do you want to be remembered for?” to “What is the best funeral you ever attended?” Because people talk about death, they support each other and are more prepared to deal with it when it happens (Death Cafe N.d.). If you would like to learn more about this conversation, watch Death Cafes video: Death Cafes: Discussing Death and Especially Life [Video].

Having the conversation and attending a death cafe are taking action at an individual and community level. However, death positivity is also a social movement. Rather than marching with signs, activists are creating compassionate communities. People are forming communities that care for each other, whether physically living together, meeting regularly, or connecting online. Hospice Palliative Care Ontario describes it this way, “A Compassionate Community is a community of people who feel empowered to engage with and increase their understanding about the experiences of those living with a serious illness, care” (Hospice Palliative Care Ontario 2019). At these individual, community, and institutional levels, we see action creating social justice. We’ll examine many more interdependent solutions as the chapter continues.

13.2.6 Licenses and Attributions for Death and Dying as a Social Problem

Open Content, Original

“Death and Dying as a Social Problem” by Patricia Antoine and Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Death positivity” definition from On Death and Dying by Jacqueline Lewis is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 13.5. “Age-adjusted death rates, by sex and race and ethnicity: United States, 2019 and 2020” by Sherry L. Murphy, Kenneth D. Kochanek, Jiaquan Xu, and Elizabeth Arias, CDC is in the Public Domain.

Figure 13.6. “All Cases and Deaths by Race and Ethnicity Among Ages 18+ in California, as of May 9, 2023.” Data from “California: All COVID-19 Cases and Deaths by Race and Ethnicity Among Ages 18+ California Department of Public Health,” California Department of Public Health.

Figure 13.7a. “Bernard Crettaz” by Erling Mandelmann is licensed under CC BY-SA-3.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 13.4. “Right to Die Movement Finds New Life” by PBS NewsHour is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 13.7b. “Jon Underwood” by an unknown artist is included under fair use.