8.3 Environmental Inequality and Culture

Kimberly Puttman and Avery Temple

The environmental crisis is a social problem because people contribute to the problem and experience it differently based on their race, class, gender, and ability among other social locations. A portion of this inequality is historically rooted in the destruction of culture caused by colonialism. To understand this, we must define both culture and colonialism.

In every interaction, we all adhere to various rules, expectations, and standards that are created and maintained in our specific culture. In Chapter 1, we learned that these social norms have meanings and expectations. When we do not meet those expectations, we may receive some form of disapproval. For example, someone trying to connect with you may ask: “What do you think of the weather we’re having?” A common response in Oregon might be, “I’m so tired of the rain.” If you ignored the question, you would be violating a norm. Alternatively, if you responded with your detailed analysis of climate change, you would also violate the norm of a “greeting.” These norms and the norm violations are concrete examples of culture.

Culture is the shared beliefs, values, and practices that are transmitted within a social group. Culture includes:

- shared values,

- beliefs that strengthen the values,

- norms, and rules that maintain the values,

- language so that the values can be taught,

- symbols that form the language people must learn,

- arts and artifacts,

- people’s collective identities and memories.

We examine social situations to discover the expectations for norms and behaviors. People who interact within a shared culture create and enforce these expectations. Sociologists examine these circumstances and search for patterns.

8.3.1 Enculturation and Cultural Universals

Anthropologist Edward Tyler (1871) was one of the earliest social scientists to define culture, stating that it was “that complex whole which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits” that people learn from other members of their group. In other words, culture is taught and learned. Anthropologists call the process of learning culture enculturation.

A Western example of enculturation is the belief that we must work to earn the right to live. Children are taught from a young age that we must work jobs until we are old to afford our basic necessities, such as food, shelter, water, and belonging within our communities. This is steadily reinforced throughout adolescence and into adulthood through toys, media, job fairs, career days, and paychecks.

All cultures have to solve similar problems: how to find enough to eat, how to raise children, how to care for the sick, and how to memorialize those who have died. Although cultures vary, they also share common elements. Cultural universals are patterns or traits that are globally common to all societies (Murdock 1949).

One example of a cultural universal is the family unit. Every human society recognizes a family structure that regulates sexual reproduction and the care of children. Even so, how that family unit is defined and how it functions vary. You might remember family difference in individualist and collectivist cultures from Chapter 7. Other cultural universals include customs like funeral rites, weddings, and celebrations of births. Each culture has them, but they may look quite different.

8.3.2 The Culture Wheel

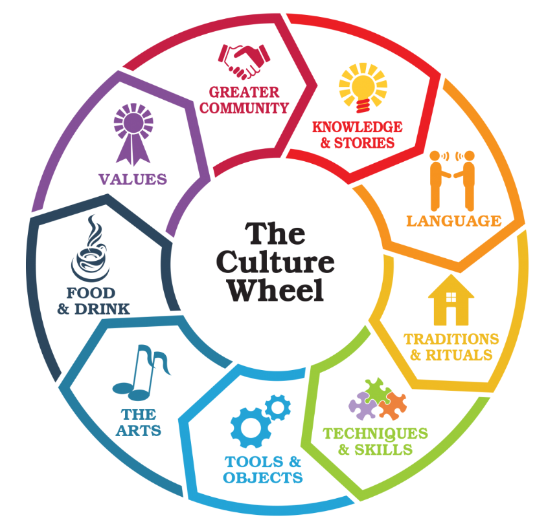

As a sociologist exploring a social problem, you might look at how the cultures of the participants reflect different values, norms, languages, or laws in order to better understand the conflict. To remind ourselves of what these cultural differences can be, we have the culture wheel to help (Figure 8.9).

Figure 8.9. The culture wheel visually represents a specific culture’s beliefs, actions, and backgrounds. The culture wheel helps us to understand what is common and different in many cultures. When you consider your own cultural background, how is it the same or different from the dominant culture? Image Description

How might you use this culture wheel to explain your own culture to someone else? You might find this difficult, because cultures can vary so widely. As we look at conflict related to the environment, we find that it is hard to resolve partly because of deep conflict between culture and the related world views.

According to Allan Johnson, a sociologist you met in Chapter 2, a worldview is:

The collection of interconnected beliefs, values, attitudes, images, stories, and memories out of which a sense of reality is constructed and maintained in a social system and in the minds of individuals who participate in it. (Johnson 2014:180)

Like culture, a worldview helps a person make sense of their world. A worldview is a perception of reality reinforced by people in a society. When worldviews conflict, they are hard to change. But before we can examine the conflict between Indigenous and colonialist world views, we need to learn more about colonialism.

Unpacking Oppression, Living Justice: Colonialism

Many schoolchildren in the United States can tell us that our country began as thirteen colonies. However, this basic understanding is a bit flawed.

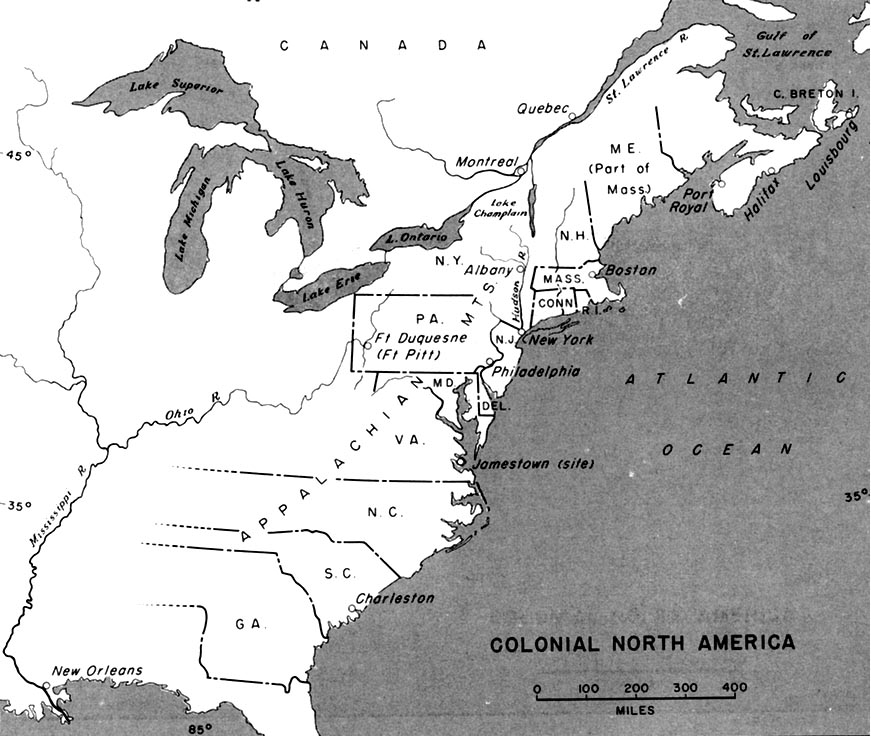

Figure 8.10. Colonial North America (1689-1783). It shows Georgia, South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, Maryland, Delaware, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire and Maine (which was part of Massachusetts). Are you surprised to see Nova Scotia, Quebec, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland?

Immediately before the American Revolution, Great Britain actually had 17 colonies. Thirteen of these colonies had a revolution. They became the new country, the United States of America. The other colonies, Newfoundland, Nova Scotia, Quebec and Prince Edward Island, remained colonies of Great Britain. These original colonies became part of the Confederation of Canada in 1867. Canada became fully independent of Great Britain in 1982.

The school child version of the thirteen colonies also simplifies a much more complicated reality. The more nuanced version of this history includes violence and genocide under the practice of colonialism.

When we say that Great Britain colonized North America, we mean that Great Britain made the laws, provided the leaders, bought animal furs, wood, and minerals, and imposed taxes. The colonizers who lived here were citizens of Great Britain, but had no rights to vote. Indigenous people and enslaved people had even fewer rights.

Figure 8.11. Please watch minutes 16-18:09 of The History of the World: Every Year [YouTube]. This time spans from 1550 to 1970. In this period, we see political colonialism increase and decrease. Note: the video itself takes the perspective of colonizers. For example, Australia shows as empty for most of the video, but we know that the Indigenous Aboriginal people live there for at least 50,000 years.

It can be challenging to imagine the sheer scope of colonial domination. Please watch the video in Figure 8.11, particularly minutes 16 – 18:09. In this video, we see that Spain, Portugal, France, England, China, and Russia were major colonizing powers. Starting about video minute 16, in the 1550s, we can see the expansion of Spain and Portugal into Central and South America. By video minute 16:30, or the1620’s, France, England, and the Netherlands established colonies in North America. By about video minute 17:17, about the year 1800, we see Great Britain establishing colonies in Australia and Canada. Much of Africa was “owned” by Spain, Portugal, and Great Britain. It was only after World War II and the rise of nationalism in the 1950s and 1960s that the power of colonialism waned. The map at video minute 18:09 shows mostly independent states worldwide.

However, very few countries are colonies now. Why is colonialism still relevant? Learning about colonialism is necessary because we still feel the effects of this historical legacy. European world powers established global slavery in this time period. Colonizers killed the people who already lived on the land through disease, war, and resettlement. As we discussed in Chapter 5, colonizers used education as a way of destroying family and community. Colonial practices fuel climate change. Part of the reason for that begins with differences in worldview.

It’s your turn to unpack colonialism and live justice:

Compare the The History of the World Every Year and the Native Lands Digital Map [website]. The Native Lands Digital Map is a Canadian project which maps where Indigenous people live today and in the past.

Consider these questions:

- Who is creating the map? (You might want to look at the About section on the Native Lands page.)

- What is included and excluded?

- What worldview does each map support?

- How might this impact climate change?

8.3.3 Worldview Conflict – Indigenous and Western Perspectives

Although Indigenous peoples worldwide are significantly different from one another, Indigenous people, social scientists, and activists agree that there is a common Indigenous worldview. From Chapter 1, we remember that the social construction of language is important. What do we mean when we say Indigenous? The United Nations describes Indigenous peoples in this way:

Indigenous peoples have in common a historical continuity with a given region prior to colonization and a strong link to their lands. They maintain, at least in part, distinct social, economic, and political systems. They have distinct languages, cultures, beliefs, and knowledge systems. They are determined to maintain and develop their identity and distinct institutions, and they form a non-dominant sector of society. (United Nations N.d.)

The United Nations doesn’t define who is Indigenous on purpose because Indigenous people have the right to identify themselves for themselves.

We’ve summarized some core differences between Indigenous and Western worldviews in the table in Figure 8.12. Each worldview defines relationships to wealth and to land, among other components. In the Indigenous view, land is sacred. Generation after generation, people care for the land and are nourished in return. Wealth is shared. In the Western worldview, land is owned or controlled. The purpose of living is to accumulate individual wealth. This belief supports the economic practices of capitalism. And, as a reminder, it is important to understand that not all Indigenous people have an Indigenous worldview. Not all Western people have a Western worldview.

|

Indigenous Worldview |

Western Worldview |

|---|---|

|

Collectiveness |

Individualism |

|

Shared wealth |

Accumulate wealth |

|

Natural world more important |

People’s laws are more important |

|

Land is sacred. We belong to the land, |

Land is a resource, is dangerous, and must be controlled. |

|

Silence is valued. |

Silence needs to be filled. |

|

Generosity |

Scarcity |

|

Binaries do not exist. |

Binaries are crucial. |

Figure 8.12. Differences between the Indigenous World View and the Western World View. Even creating a chart that divides things into two categories is an example of the Western Worldview.

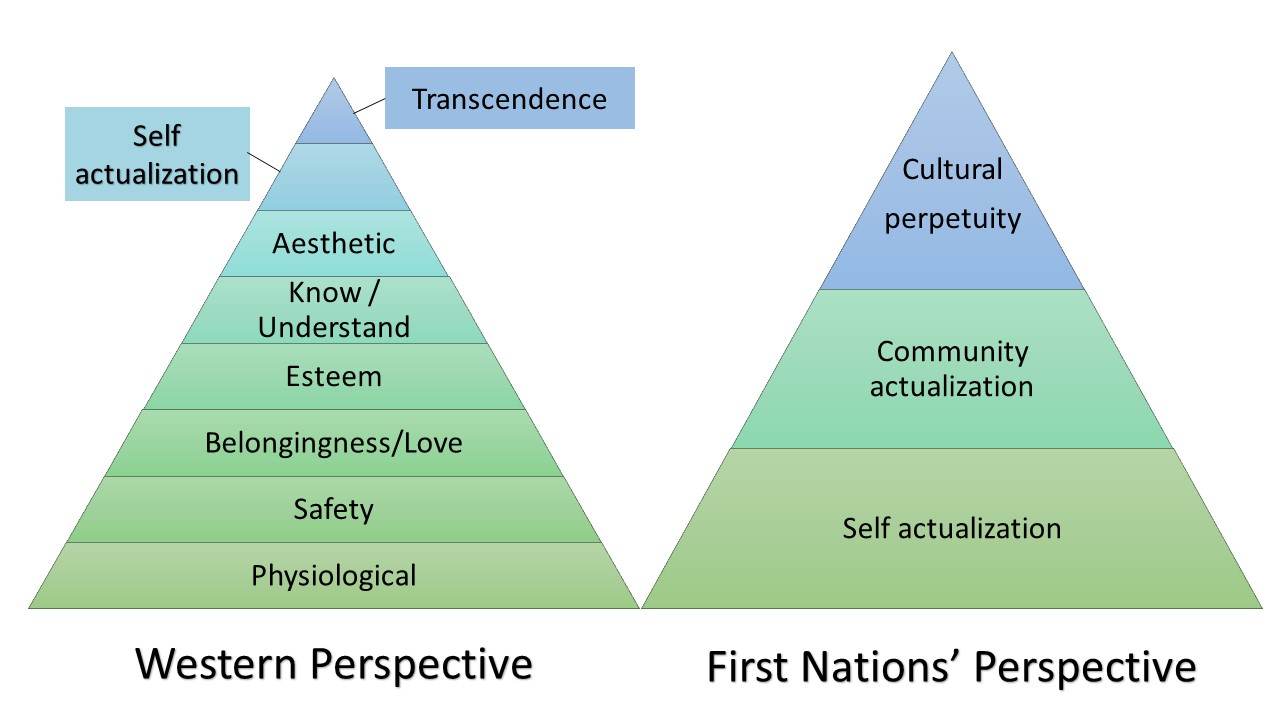

We also see a difference in worldview when we examine how we understand what people need to thrive and grow. You may have seen the triangle on the left of Figure 8.13 at some point in your education. In Figure 8.13, the triangle (left) shows Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

Figure 8.13. Comparison between Maslow’s Hierarchy, labeled as Western Perspective, and First Nations Perspective. Image description.

In 1938, American psychologist Abraham Maslow spent time with the people of the Blackfoot Nation in Canada prior to releasing his Hierarchy of Needs theory (Figure 8.13). Historians think he based the teepee-like structure on ideas from the Blackfoot Nation in North America, but westernized it to focus on the individual rather than the community (Bray 2019).

Maslow focuses on the needs of the individual, starting with the basic physical needs like food, water and shelter, moving to needs related to relationships and belonging, and then on to the highest level needs of becoming your best self.

In comparison, the ideas of the Blackfoot nation emphasize community. The well-being of the individual, the family, and the community are based on connectedness. Self actualization is actually the first layer not close to the last. Community actualization reflects our connection to family, friends, community and the world. We thrive when we contribute to and receive from our community. In addition, this model focuses on time. The top of the teepee is cultural perpetuity. It symbolizes a community’s culture lasting forever.

To learn more about Indigenous worldview from an Indigenous person please read this story, “What I Learned from Coyote,” and this explanation of worldview, “As I had shared with Coyote.” if you like. In them, Jennifer Anaquod, Indigenous educator, researcher, and member of the Muscowpetung Saulteaux First Nation in Saskatchewan, describes her worldview through story. Describing the world through story is part of Indigenous culture.

As powerful as cultures and worldviews are, they need action in the world to become real. One institution that encapsulates our values is the economy. Let’s look next at how colonialism and capitalism work together to exacerbate the social problem of climate change.

8.3.4 Colonialism, Capitalism, and Climate Change

An example that illustrates the differences between the dominant Western perspective today versus the Indigenous or First Nations perspective is the economic system of capitalism. Capitalism is an economic system based on private ownership and the production of profit. This economic system requires endless consumption and use of resources, which is not sustainable on a finite planet.

When the goal is profit, people must buy more and more things. Creating more and more things uses even more planetary resources. This drive for profit shapes our values and our behaviors. For example, capitalism often requires conspicuous consumption, the purchase of expensive luxury goods or services to display one’s wealth and status. It is not enough to have a small house with running water, heat, and electricity.

Instead, capitalism requires that people always want more: a mansion, two cars, a swimming pool, and a fancy vacation. We can see conspicuous consumption at work when we examine what people eat around the world. If you want to learn more, The Great Global Food Gap [website] shows images of what families across the globe buy for food. (Please note: as of 2023, a British pound (£) is worth slightly less than a United States dollar ($)). How much must you spend on food to meet your basic needs? How does that amount change when considering a diet that will make you happy?

Figure 8.14. Carvers Owen James, Herb Sheakley, and tribal member George Dalton, Jr. hoist the Kaagwaantaan house post. They use Traditional Ecological Knowledge to craft art and homes. How does this knowledge reflect a unique worldview?

Unlike capitalism, Indigenous economic systems do not rely on exponential growth and consumption. Many journals from early colonists describe the Americas as places with lush and ample resources. Indigenous peoples had consistently managed and stewarded the land using techniques perfected throughout generations. This knowledge today is called Traditional Ecological Knowledge, or TEK (NPS 2023a). To learn more about TEK, read Native Knowledge: What Ecologists Are Learning from Indigenous People [website].

In addition to the decimation of Indigenous populations and the land that they lived on, colonization supported a worldview that contributed to ecological devastation today. In this view, land should be owned and subjugated, rather than tended and cared for. In the words of authors Laura Dominguez and Colin Luoma (who write using UK English):

The widespread plunder of natural resources was a hallmark of colonisation. Nature was something that was to be commodified in order to enrich the colonial power. In turn, indigenous territories were treated as business enterprises, with seemingly unlimited resources to exploit. Undoubtedly, this had dire environmental consequences…. The ideology that emerged was that nature was something that should be first exploited, then preserved, but all without the input, involvement, or participation of indigenous populations. (Dominguez and Luoma 2020)

Further, colonization supports a worldview that leads its participants to value individual well-being above all else. This leads to a lack of action and concern regarding the well being of our neighbors, plants, and animals who surround us.

An example from Latin America shows the link between colonization, capitalism, and climate change. Uruguayan journalist and poet Edwardo Galeano wrote Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent in 1971. In it, he argued that capitalism based on colonization created poverty in Latin America. He writes:

Latin America is the region of open veins. Everything from the discovery until our times, has always been transmuted into European–or later–United States– capital, and as such has accumulated on distant centers of power. Everything: the soil, its fruits and its mineral-rich depths, the people and their capacity to work and to consume, natural resources and human resources. (Galeano 1971:2)

He also wrote a poem “Las Nadies/The Nobodies,” which describes the impact of colonial capitalism on the people who live in the colonized countries. In it, the people are nobodies. He wrote, “We don’t have culture, but folklore,” among other losses. The people who contribute the least suffer the most cultural and economic loss. If you’d like to listen to this poem, watch Los Nadies/The Nobodies Poem [Video].

The legacy of colonialism and capitalism on climate change continues in Latin America today. The world markets for beef, soybeans, palm oil, wood products, sugar, and coffee support continued deforestation (Union of Concerned Scientists 2016). Deforestation itself is a cause of climate change.

Environmental inequality arises from cultural differences in worldviews, and the economic systems that derive from these worldviews. This conflict provides the context for making sense of the climate crisis today.

8.3.5 Licenses and Attributions for Environmental Inequality and Culture

Open Content, Original

“Environmental Inequality and Culture” by Kimberly Puttman and Avery Temple is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Unpacking Oppressing, Living Justice: Colonialism” by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.12. “Differences between the Indigenous World View and the Western World View” by Avery Temple is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

“Environmental Justice” definition by Kimberly Puttman is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Adapted from “Dumping in Dixie: Race, Class, and Environmental Quality” by Robert D. Bullard, Westview Press.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Enculturation and Cultural Universals” is adapted from “Introduction” and “What is Culture” by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, and Asha Lal Tamang, Introduction to Sociology 3e, Openstax, which is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Modifications: Summarized some content and applied it specifically to the social problem of climate change.

“Conspicuous Consumption” definition is adapted from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary edited by Kenton Bell, which is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

“Cultural Universals” and “Culture” definitions from Introduction to Sociology 3e by Tonja R. Conerly, Kathleen Holmes, Asha Lal Tamang, Openstax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 8.10. “Colonial North America 1689 to 1783” by United States Army Center of Military History is in the Public Domain

Figure 8.13. “Maslow’s Hierarchy and First Nations Hierarchy” from “Connection” by Elizabeth B. Pearce, Wesley Sharp, and Nyssa Cronin, Contemporary Families: An Equity Lens 1e is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Based on research from Rethinking Learning by Barbara Bray.

Figure 8.14. “Carvers Owen James and Herb Sheakley, and tribal member George Dalton, Jr. hoist the Kaagwaantaan house post” by the National Park Service is in the Public Domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 8.9. “The Culture Wheel” © AndreaGrace J. Fonte Weaver is all rights reserved and included with permission.

Figure 8.11. “The History of the World Every Year” by Ollie Bye is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.