9.2 Applying the Social Problems Process to #BlackLivesMatter

Nora Karena

Recall from Chapter 1 that most social problems go through a social problems process consisting of the following stages of development: claimsmaking, media coverage, public reaction, policymaking, social problems work, and policy outcomes (Best 2021:15). In this section, we will trace this pattern through the Portland protests of 2020. This section also explores inequalities in class, race, and policing. As you read, consider how you have observed this pattern in other social problems.

9.2.1 Claimsmaking and Media Coverage

Claimsmaking: In this step, people and groups identify an issue, and they try to convince others to take it seriously. The problem in this step is called a claim “an argument that a particular troubling condition needs to be addressed” (Best 2020:15). In this stage, people who may not agree that a problem exists agree on what to do about it or who should take action

Media Coverage: In the second step, claimsmakers use media to build a base of people and groups who agree with them on the causes, impacts, and desired outcomes of the particular issue at hand.

Figure 9.2. George Floyd was one of a very long list of Black people killed by police and vigilantes in the US. Did you see video footage of Mr. Floyd’s Murder? How did it impact you?

On Monday, May 25, 2020, Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd. One of four Minneapolis police officers who arrested Floyd for allegedly trying to pass a counterfeit twenty-dollar bill, Chauvin forced Floyd to the ground and knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes. Floyd struggled to breathe, cried out in fear and pain to his mother and to his God, and foretold his own death, but Chauvin did not let up until Floyd lost consciousness. Floyd was pronounced dead at the hospital later that afternoon. Like Ahmaud Arbery, killed by White vigilantes in February 2020, and Breonna Taylor, killed by police in March 2020, Floyd is one on a very long list of Black people killed by police and vigilantes in the US (Figure 9.2).

Horrified bystanders captured a video of Floyd’s murder and shared it on social media. In the first week after Floyd’s murder, 3.4 million original posts and 69 billion engagements accounted for around 15% of all posts on Twitter during that week. By June 8th, #BlackLivesMatter was mentioned in 1.2 million original posts (Wirtschafter 2021).

However, this hashtag didn’t start in 2020. #BlackLivesMatter is a hashtag that first went viral in 2013 in response to the acquittal of Trayvon Martin’s murderer. In the decade following its introduction, #BlackLivesMatter became a popular organizing tool on social media. This hashtag draws attention to racist violence in the US It is a code for a set of claims about racism, policing, lynching, and underserved communities. Underserved communities are groups with limited or no access to resources or are otherwise disenfranchised (FEMA 2023).

9.2.2 Claim: Lynching and Racist Policing

Figure 9.3. Journalist Ida B. Wells wrote Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases in 1892 to expose the racial violence in the South. Do you see evidence of racial violence in your community?

Lynchings are extrajudicial killings in which an individual or a mob kidnaps, tortures, and kills persons suspected of crime or social transgressions. Extrajudicial killings are murders by a person with authority, without any legal process (OMCT World Organization Against Torture 2023). In the US, the victims are most often Black men, women, and children. The perpetrators are almost never punished. More than 4,400 lynchings have been documented in the US between 1877 and 1950 (Taylor and Vinson 2020). Racially motivated lynchings are a means of social control that reinforces the dominance of White people within a racial hierarchy.

In the late 19th and early 20th Century, the journalist Ida. B. Wells wrote about lynchings as part of her work to document discrimination against Black people (Figure 9.3). She found that the prevalent myth that Black men were lynched because they raped White women, was just that – a lie. Instead, she argued that lynching was a method of social control to suppress Black freedom and the right to vote by violence and murder.

Sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois, who we met in Chapter 3, led the N.A.A.C.P. in an anti-lynching campaign that reduced lynchings. This campaign inspired the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-20th century. Despite the progressive gains these movements achieved, the murder of Trayvon Martin, an unarmed teenager on his way home, and the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the man who killed him, was a painful reminder that the extrajudicial killing of Black people has never stopped. Explicit racial bias has been demonstrated in some police departments. In a 2022 investigation of the Minneapolis Police Department, researchers found that:

…based on interviews and a review of 700 hours of body camera footage, identified an exhaustive list of slurs that officers and supervisors consistently use against women and Black people, including suspects, witnesses, bystanders and their own colleagues. (Dewan 2022)

They also identified “patterns of discrimination in arrests and use of force (Dewan 2022).”

Portland police also have a well-documented record of individual police officers expressing racist ideas about Black people. A 2012 report documents a long and troubled history of racist policing, including an incident of harassment in which several Portland officers left dead animals at a popular restaurant owned by a Black person. You have the option to read the full 2012 report, Black and Blue: Police-Community Relations in Portland’s Albina District, 1964-1985.

Figure 9.4. Robin DiAngelo is a White working class educator and the author of White Fragility and Nice Racism. She has written extensively about the lengths people will go to to avoid being labeled racist, even when expressing racist ideas. Have you ever been told you were being racist? How did that make you feel? Did you take action to change or heal the harm?

Violence arises from prejudice. As you might remember from Chapter 5, prejudice is an unfavorable preconceived feeling or opinion formed without knowledge or reason that prevents objective consideration of an individual or group. Many advocates for police and policing resist claims of racism by asserting that such attitudes are the result of individual prejudice held by a few “bad apples” rather than a culture of racism. Robin DiAngelo (Figure 9.4), an educator who studies racism, has written extensively about the lengths people will go to to avoid being labeled racist, even when expressing racist ideas (DiAngelo 2018). Most people, including police officers, resist being thought of as racist, but individual racial bias is only one dimension of racism.

Claims of racism and racist policing also rest on racial disparities and historical patterns of policing. Racial disparity is the unequal outcomes of one racial or ethnic group compared with outcomes for another racial or ethnic group (Children’s Bureau 2021:2). Racial disparities are sometimes called racial inequities. For example, BLM organizers and their allies point to higher percentages of Black people being stopped, arrested, imprisoned, and killed by police than White people. In Portland, Black people make up only 5.3% of the city population, yet they account for 22.6% of traffic stops and 16 % of pedestrian stops in 2019. They are also arrested at a rate 4.3 times higher than White people. Furthermore, Black people are killed by Portland police 3.9 times more than White people (Levinson 2021).

This pattern of racial inequity repeats in cities across the US A 2020 study found “that while Black people were much more likely to be pulled over than Whites, the disparity lessens at night, when police are less able to distinguish the race of the driver.” The study also found that Black people were more likely to be searched after a stop, though White people were more likely to be found with illicit drugs (Pierson et al. 2020). In the US, Black men are about 2.5 times more likely to be killed by police than White men. Black women are about 1.4 times more likely to be killed by police than White women (Edwards, Lee, and Esposito 2019).

Claims of racist policing also rest on scholarship about the history of policing in America. For example, Irish police officers in 1830’s Boston were specifically hired to police communities of formerly enslaved people who were Black (NPR 2020). Slave patrols and Jim Crow-era policing of Black communities are well documented (NAACP N.d). Please watch this brief video to learn more about this history (Figure 9.5).

Figure 9.5. Please watch the 4:51 video, NPR Throughline, History of Policing in America [YouTube], to learn more about the history of policing. What structural and individual causes of racist policing do you see? Transcript

This historic construction of racist policing recalls Racial Formation Theory. We explored this theory by Omi and Winant (1986) in Chapter 3. The theory describes how racial classifications are created, changed, and recreated through racial projects, like policing, which attach meaning and power to racial categories. Policing becomes a racist practice when Black people get profiled as more likely to be considered a threat to public safety than White people.

Critical Race Theory, also introduced in Chapter 3, helps us understand how legal statutes like The Anti-Drug Abuse Act of 1986 (H.R.5484) actually create and sustain racial inequity. Another institution that contributes to racial inequities is the United States Criminal Justice System, which relies on legal codes, criminalization, policing, and punishment to mediate conflict, protect property, and maintain social order.

These laws include the Crime Bill (H.R.3355), which significantly expanded prisons and funded 100,000 new police officers. They also include the 1998 Amendments to the Higher Education Act of 1965 (HEA), which limits access to financial aid for students who have been convicted of a drug felony (Whitman and Exarhos 2020).

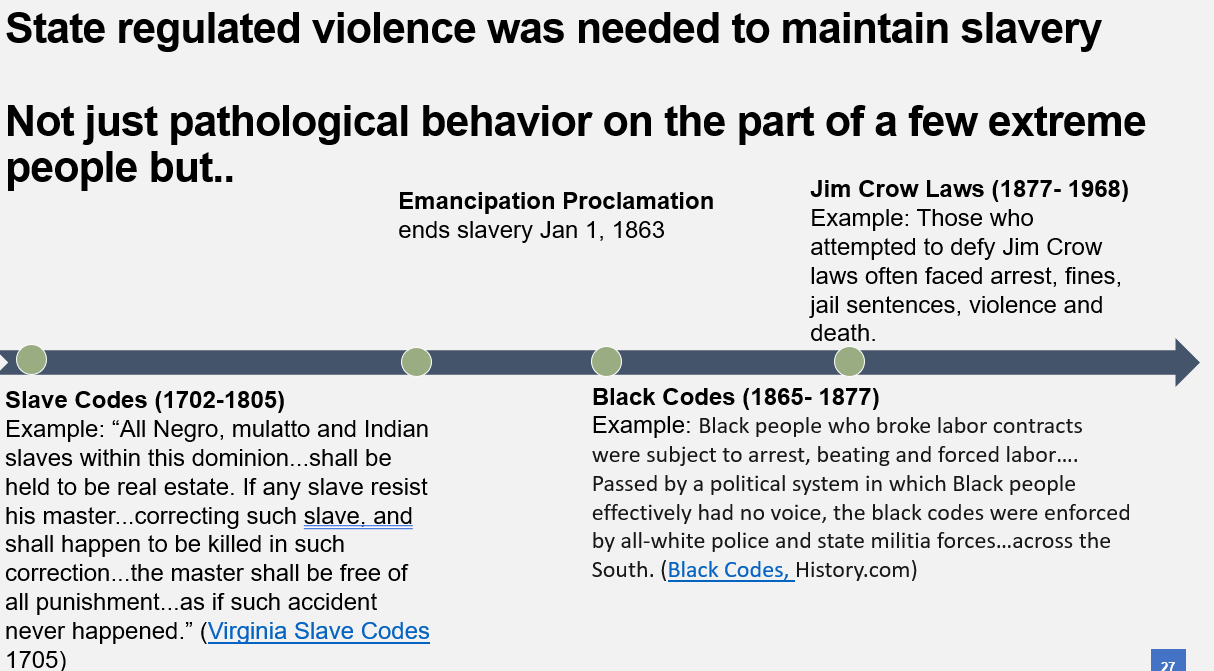

Figure 9.6. State regulated violence was needed to maintain slavery and subsequent racial inequality, using Slave Codes, Black Codes, and Jim Crow laws. Although these three sets of laws are illegal, where do you see racial inequality supported in other laws, policies, or practices? Image description.

Critical race scholarship further places this legislation within the historical context of legal statutes that regulated Black lives. A timeline of these laws and policies is shown in Figure 9.6. These laws began with the Slave Codes. After the Civil War, Slave Codes became Black Codes. They restricted Black people’s right to own property, conduct business, and move freely through public spaces. They fed a convict leasing system that replaced slavery as a source of cheap labor for enslavers. Black Codes then became Jim Crow Laws in many states, legally segregating Black people and White people. In each case, the laws reinforced the racist and incorrect ideas that Black people were dangerous and needed controlling. These ideas are wrong.

9.2.3 Claim: Under-resourced Communities

This claim centers the social devastation of historic racism in BIPOC communities. BIPOC is an acronym that stands for Black, Indigenous, and People of Color. It is used to refer to people whose communities have been historically under-resourced, over-policed, disproportionately impacted by social problems, and underrepresented in terms of institutional power in the United States because of their assigned race category.

The history of exclusion, segregation, and discriminatory lending practices described in Chapter 6 created the social and economic conditions in the under-resourced communities we are looking at in this chapter. Under-resourced communities are areas with relatively high poverty rates that lack robust economic infrastructure. While the term often refers to cities and suburbs with populations of over 250,000 people, many rural communities are also under-resourced (adapted from Eberhardt, Wial, and Yee 2020:5). In the South, Midwest, and Northeast, these neighborhoods are disproportionately Black. In the West, these neighborhoods are disproportionately Latinx.

The legacy of economic exclusion and discrimination is well demonstrated in a 2014 report from Portland State University. The report found that African-American family income is less than half that of White families. The poverty rate among African-American children is nearly 50% compared to 13% for White children. Local unemployment levels in 2009 for African-American people were nearly double the unemployment rate for White people.

Researchers also found that “fewer than one-third of African-American households own their homes, compared to about 60% of White households, and that African-Americans have experienced housing displacement and the loss of community as the historic Albina District has gentrified” (Coalition of Communities of Color 2014:3). The same study also documented substantial disparities for health outcomes like diabetes, stroke, and low birth weight, and in access to health insurance, prenatal care, and mental health care. If you would like to read the full report, consider how The African American Community in Multnomah County: An Unsettling Profile [Report], clearly documents racial inequality.

Demands for police reform and prison abolition argue that policing and the prison system are inadequate responses to the social problems that impact historically disadvantaged communities. The call for “defunding the police” is a call for recognizing that poverty is not caused by crime and for redirecting resources to programs that actually support the well-being of communities disproportionately impacted by poverty.

Figure 9.7. Social geographer and Black activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore traces the physical locations of prisons to better understand how economic systems create privilege and oppression. Along with Angela Davis, she champions prison abolition. What do you think a world without prisons would be like?

Social geographer Ruth Wilson Gilmore (Figure 9.7) applies a Marxist analysis to the economic conditions that accompanied the massive expansion of prisons in California. She demonstrates that the US prison system grew to contain and control surplus labor as low-wage workers in historically disadvantaged communities lost access to jobs during the 1980s and 1990s. She also argues that mass incarceration prevents displaced workers from building robust labor movements that might challenge these exclusionary economic conditions (Wilson Gilmore 2007).

In 1996, Gilmore partnered with Angela Davis, whom we met in Chapter 1, to organize Critical Resistance, a social movement organization that challenges the idea that imprisonment and policing are acceptable solutions for social, political, and economic problems. The contemporary prison abolition movement, with which many BLM organizers are aligned, can trace its roots to these organizing efforts. Please click the link if you’d like to learn more about Critical Resistance.

9.2.4 Public Reaction

Public Reaction: According to Best, in this step, individuals, groups, and organizations begin to align to a particular explanation of the problem and request a change in policy or law. Most of the time, at this step, it is the power of social movements that create the changes in policy or law.

A protest is a public expression of objection, disapproval, or dissent towards an idea or action (Definition of Protest 2023). Social movements have used sustained protests to disrupt civic life, draw attention to how the system is not working, and demand change. Protests began on May 26, 2020, in Minneapolis and around the US, growing to more than 7700 Black Lives Matter-inspired protests by mid-August. Juneteenth weekend alone saw as many as 25 million people in the US, including many celebrities and public figures, publicly demand justice and change.

Figure 9.8. The Pacific Northwest Youth Liberation Front protested during Black Lives Matter protests in Portland, Oregon. Why do you think young people emerge as leaders in movements for social justice?

On Thursday, May 28, 2020, the Pacific Northwest Youth Liberation Front (PNYLF) (Figure 9.8) organized a protest at The Multnomah County Detention Center demanding an end to state-sanctioned violence against Black people. The young, mostly White protesters chanted, “Black Lives Matter,” “I Can’t Breathe,” and “Defund the Police.” PNYLF followers describe themselves as a “decentralized network of autonomous youth collectives dedicated to direct action towards total liberation (Graves 2020). For PNYLF, total liberation includes ending mass incarceration. If you would like to learn more about the history of mass incarceration, check out this fact sheet from The Brennan Center for Justice.

The people who attended the official NAACP protest the next day were also predominantly White. Black civil rights leaders, including past and current leaders of the NAACP, The Portland Urban League, and a City Commissioner, along with local faith leaders, rallied around a symbolic plywood casket. The casket was surrounded by banners to honor the murdered—George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Micheal Brown, and Ahmaud Arbery. They called for an end to racist policing. They called on the growing crowds to “Stop killing us!” and to “Carry your White privilege to the point that it makes a difference.” Despite the peaceful tone of the day, tempers and provocations flared with urgency as evening fell. Police and protesters clashed, and the Portland mayor declared the protest a riot (Graves 2020).

By the third night, the mayor declared a state of emergency, and parts of downtown Portland were boarded up. While most protests were peaceful and non-violent, news reports in July 2020 estimated that damage from the riots cost local businesses, mostly in the vicinity of the Multnomah County Justice Center, about $23 million dollars. Later reports reminded us that a significant portion of the lost revenue was related to COVID-19 business closures, not looting and vandalism (Bailey Jr 2020).

More protesters filled the streets each night. Violence escalated when militarized federal agents were deployed in the streets of Portland. Federal officials, including the Attorney General and the President, defended the action as necessary to protect federal property and to “prevent violence from spreading to other American cities.” Many state and local leaders argued that federal intervention was an unnecessary political stunt that only further escalated tensions (Graves 2020).

Figure 9.9 a and b. Black Lives Matter protesters in Portland included some unexpected groups like the Wall of Moms and Dads with Leaf Blowers. Who protested in your community?

The protesters, now in the thousands, responded as a Wall of Moms, Dads with leaf-blowers, (figures 9.9 a and 9.9 b), a naked White woman, along with a mostly White, multigenerational multitude of first-time protesters, who took turns confronting heavily armed federal forces and demanding an end to racist policing while declaring loudly that “Black Lives Matter.” If you would like to learn more about these protesters, please read these articles: “Hear from the “Wall of Moms”, Dad’s with leaf-blowers, and ‘Naked Athena’: The story behind the surreal photos of Portland protester,

On July 30th, Oregon State Police were once again responding to the protests as federal agents began to withdraw, and the protests became more peaceful, though no less urgent.

The charged protests in downtown Portland were not the only protests for Black Lives in the state. Thirty-three Oregon towns saw overwhelmingly peaceful protests like the 25-50 people enthusiastically singing “Black Lives Matter” as they paraded up and down the main street in Manzanita every weekend throughout that grim COVID summer. More than 2,000 cities in 60 countries around the world saw similar protests (Wikipedia 2022).

It was and remains a contested, often heated conversation. Around the state, smaller groups of pro-police counter-protesters refuted claims of racist policing in Oregon and declared that, in fact, “Blue Lives Matter.”

9.2.5 Policy Making, Social Problems Work, and Policy Outcomes

The last three steps in Best’s model of the social problems process are policymaking, social problems work, and policy outcomes. As a reminder:

Policy Making: In the policy making step, governments create new laws, and institutions create new policies to implement a response to a social problem.

Social Problems Work: Once a new policy is put into place or the law is signed, institutions must act to implement the change.

Policy Outcomes: In this step, claims makers examine the outcomes of the policies and actions taken to respond to the social problem. Often, the outcome of this step is the refinement of a claim and a request for more action.

Protests were not the only way Oregonians responded to the murder of George Floyd. The small town of Vernonia was one of several that issued resolutions supporting equality and inclusion. Book clubs and racial equity work groups were convened. BLM took center stage as the whole state seemed to enter into an urgent public conversation about racism in Oregon, alternatives to policing, and what it might look like if Black lives really mattered here. If you’d like to learn more about this work, please review the blog Victory in Vernonia.

In June, more than 800 people, organized by Unite Oregon and Imagine Black, testified at city budget hearings and urged city officials to redirect $50 million dollars from policing to community support and to sever connections between Portland Public Schools and the Portland Police Bureau. The city budget cut $15,000,000 in funding for School Resource Officers and two other controversial policing programs. The Mayor also responded with a list of 19 proposed police reforms, 13 of which he achieved within the year. If you would like to learn more about Unite Oregon and Imagine Black, please check out their websites.

In July 2020, The Electoral Justice Project of the Movement for Black Lives introduced the Breathe Act, which “offers a radical reimagining of public safety, community care, and how we spend money as a society.” Two Members of Congress, Rashida Talib and Ayanna Pressley stepped up to champion the measure’s “four simple ideas”:

- Divest federal resources from incarceration and policing.

- Invest in new, non-punitive, non-carceral approaches to community safety that lead states to shrink their criminal-legal systems and center the protection of Black lives—including Black mothers, Black trans people, and Black women.

- Allocate new money to build healthy, sustainable, and equitable communities.

- Hold political leaders to their promises and enhance the self-determination of all Black communities (Movement For Black Lives 2020).

You can learn more about the Breathe Act if you would like to.

In April 2021, the Portland City Counsel’s Racial Equity Steering Committee issued a 65-page report with recommendations for police reform that included improved racial equity training and assessment, along with proposed changes in the way law enforcement responds to houselessness and mental health crises (Abdurraqib 2021).

In 2021, the Oregon legislature passed HB 2930 to hold police more accountable for sexual assault and racial bias. By August 2022, the commission formed to draft the new rules and released a draft proposal for public comment. The proposal has been widely criticized for being too lenient and allowing officers who commit serious crimes to keep their jobs (Levinson 2022).

Portland police followed through on several of the requests, including more robust anti-bias training (Byrne 2021). Police agencies across the state have prioritized increasing racial and gender diversity in their recruitment and have begun to screen new hires for racial bias. However, these efforts have not been broadly supported by police officers. The majority of police personnel surveyed in 2021 thought that additional anti-bias training was unnecessary, and 15% of respondents said they had plans to leave within the year. A respondent quoted in the report described a general feeling within the rank and file that had been “betrayed” by “city leaders, elected officials, and community” (Gennaco et. al. 2022:47). Those who advance an abolitionist vision, in which there are no under-resourced communities, assert that we can’t train our way out of racism.

A growing coalition of organizers emerging from the 2020 protests continues to work towards decarceration, transformative justice, and community care. For example, Don’t Shoot PDX, which was organized in 2016, continues to offer programming for young people impacted by racial injustice and police violence, as well as “mutual aid [including] food, household supplies, and clothing distributions to marginalized families, houseless communities, indigenous reservations and rural populations in the region” and legal outreach community members who experience racism and discrimination (Don’t Shoot PDX 2022). If you’d like to learn more about Don’t Shoot PDX, you can check out their website at Don’t Shoot PDX.

9.2.6 Unpacking Oppression: Anti-Racist Social Justice

Before we discuss how sociologists might explain the inequalities that resulted in #BlackLivesMatter, it is important to understand how racism works. It is even more important to harness our own antiracist power. Let’s dive deeper!

Recall from Chapter 2 that identities are socially constructed, and that meanings change over time. When we think about how racism works as the sum total of racist policies, ideas, and inequitable outcomes, we can understand how racism is a process by which racial identity is socially constructed and reconstructed.

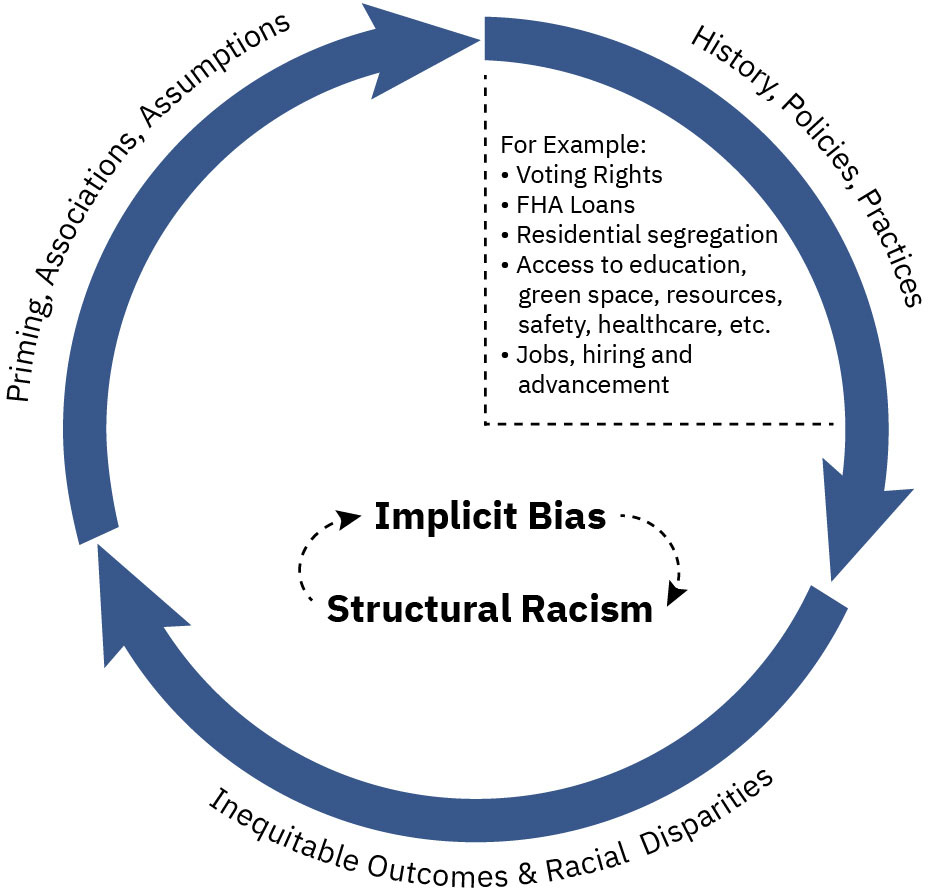

Figure 9.10. Implicit Bias and Structural Racialization (Osta and Vasquez N.d.). While racial bias is a component of racism that must be acknowledged and addressed, it is also critical to understand the work racial biases and other racist ideas do to justify specific policies, which produce and sustain inequitable outcomes and racial disparities. This is why antiracism pays attention to policy change as well as challenging racist associations and assumptions. You can practice antiracism by answering the “Your Turn” questions at the end of this section. Image Description

Have you ever had or heard a conversation like this?

“What do you mean, Black lives matter? Don’t you mean all lives matter?”

“Of course, all lives matter, but it doesn’t seem like Black lives matter when people who are Black are being killed by police and imprisoned at higher percentages than people who are White, and it’s been that way for a long time. If Black lives mattered more, the police wouldn’t be killing and locking up so many Black people.”

When Alicia Garza, Patrice Cullors, and Ayo Tometti boldly proclaimed that Black Lives Matter, they gave us a framework for talking about racism that challenges social norms about calling out racism.

If we only think about racism as hateful feelings about people who are different, we miss the systems and social structures that those ideas inspired. A common definition of racism is racial prejudice plus power equals racism. In other words, racist ideas, which can be conscious or unconscious, can inspire interpersonal hostility, but personal or institutional power is required for racist actions to occur. If you’d like a deeper dive into how the racist ideas we learn can become implicit bias, check out module one from Kirwan Institute’s Implicit Bias Module Series.

It can also be useful to look beyond individual biases and think about racism in terms of structural racism and institutional or systemic racism. As we learned in Chapter 3, structural racism refers to the social structures that emerge from racist ideas, policies, and practices and which produce racial inequities. Structural and systemic racism can be identified by the presence of racial inequity.

Racial inequity shows up as either disproportionality or disparities. As a reminder, disproportionality is the overrepresentation or underrepresentation of a racial or ethnic group compared with its percentage in the total population. Disparities are unequal outcomes of one racial or ethnic group compared with outcomes for another racial or ethnic group.

For example, when Black people are killed by Portland police 3.9 times more than White people, we recognize outcome disparities (Levinson 2021). If you’d like to review this data for yourself, please read Portland has 5th worst arrest disparities in the nation according to data [website]. Similarly, since Portland police arrest Black people at a rate 4.3 higher than White people, we can say that Black people are over-represented in Portland jails. Because those inequities are racially defined, we can say that the institution or system, in this case, policing in Portland is racist.

Once constructed, racist systems and institutions can continue to impact people unevenly, even if the people who currently hold power do not share all of the same founding racist ideas (Bonilla-Silva 2015). Understanding the structural and systemic dimensions of racism helps us understand how persistent racist policies, procedures, and systems can sustain racial inequity, even as racist ideas begin to recede or at least change.

It’s your turn to unpack oppression and create antiracist social justice

The historian Ibram X. Kendi describes an anti-racist as someone supporting an antiracist policy through their actions or expressing an antiracist idea (Kendi 2019:13). To better understand the relationships between racist ideas, racist policies, and racial inequities, try this exercise:

Step 1: Identify a racial inequity (disparate outcome or a disproportionate representation) related to a social problem you have learned about in this book.

Step 2: Identify some of the policies, practices, or historical legacies that create or maintain the inequity.

Step 3: Identify some of the racist ideas that justify the policies or practices.

Step 4: Practice being anti-racist by identifying at least one policy that would reduce the inequity and one anti-racist idea that would challenge the racist idea.

Step 5: What are actions you can take to:

- Support policy changes that could reduce racial inequities?

- Challenge the racist ideas that support old racist policies?

If you need help visualizing this process, the chart in Chapter 6, Figure 6.18, Racist Policies, Racist Inequities, and Racist Ideas in Housing might be useful.

9.2.7 Licenses and Attributions for Applying the Social Problems Process to #BlackLivesMatter

Open Content, Original

“Applying the Social Problems Process to #BlackLivesMatter” by Nora Karena is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 9.6. “Infographic: State Regulated Violence Was Needed to Maintain Slavery” by Kimberly Puttman and Michelle Culley, Open Oregon Educational Resources, is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Prejudice” definition by Nora Karena is adapted from the Open Education Sociological Dictionary by Kenton Bell, and is licensed under CC BY SA 4.0.

“Racial Disparity” definition from “Child Welfare Practice to Address Racial Disproportionality and Disparity” (p. 2) by the Children’s Bureau is in the Public Domain.

“Underserved Communities” definition from “Glossary” by FEMA is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.2. “George Floyd Memorial” by Fibonacci Blue is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Figure 9.3. “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases, book cover, 1892” by Ida B. Wells is in the Public Domain.

Figure 9.4. “Robin DiAngelo, PhD, 2021” by Jason P Toews is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

Figure 9.7. “Ruth Wilson Gilmore” by Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 9.9a. “Untitled_1.23.1” by Tony is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

All Rights Reserved Content

“Your Turn Exercise” inspired by Kendi, Ibram X. 2019. How To Be An Antiracist. New York: One World.

“Under-resourced Communities” definition is adapted from “The New Face of

Under-Resourced Communities” (p. 5) © Peter Eberhardt, Howard Wial, and Devon Yee

Initiative for a Competitive Inner City and is included under fair use.

Figure 9.5. “History of Policing in America | Throughline” by NPR Podcasts is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.

Figure 9.8. “Photo of The Pacific Northwest Youth Liberation Front” by PNWYLF is included under fair use.

Figure 9.9b. “Portland dads” by Hermits United is included under fair use.

Figure 9.10. “Implicit Bias and Structural Racialization” by National Equity Project is included under fair use.