6.1 Learning

Stevy Scarbrough

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this reading, you will be able to:

- Describe the Uses and Gratification Model as it applies to motivation and learning.

- Describe the benefits of using different learning styles for various subjects and activities.

- Describe the different levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy.

- Describe how to make decisions about your own learning.

To begin with, it is important to recognize that learning is work. Sometimes it is easy and sometimes it is difficult, but there is always work involved. For many years people made the error of assuming that learning was a passive activity that involved little more than just absorbing information. Learning was thought to be a lot like copying and pasting words in a document; the student’s mind was blank and ready for an instructor to teach them facts that they could quickly take in. As it turns out, learning is much more than that. In fact, at its most rudimentary level, it is an actual process that physically changes our brains. Even something as simple as learning the meaning of a new word requires the physical alteration of neurons and the creation of new paths to receptors. These new electrochemical pathways are formed and strengthened as we utilize, practice, or remember what we have learned. If the new skill or knowledge is used in conjunction with other things we have already learned, completely different sections of the brain, our nerves, or our muscles may be tied in as a part of the process. A good example of this would be studying a painting or drawing that depicts a scene from a story or play you are already familiar with. Adding additional connections, memories, and mental associations to things you already know something about expands your knowledge and understanding in a way that cannot be reversed. In essence, it can be said that every time we learn something new we are no longer the same.

In addition to the physical transformation that takes place during learning, there are also a number of other factors that can influence how easy or how difficult learning something can be. While most people would assume that the ease or difficulty would really depend on what is being learned, there are actually several other factors that play a greater role.

In fact, research has shown that one of the most influential factors in learning is a clear understanding about learning itself. This is not to say that you need to become neuroscientists in order to do well in school, but instead, knowing a thing or two about learning and how we learn in general can have strong, positive results for your own learning. This is called metacognition, you learned about it in section 5.2.

Some of the benefits to how we learn can be broken down into different areas such as:

- motivation for learning,

- types of learning goals,

- and methods of learning.

In this section you will explore these different areas to better understand how they may influence your own learning, as well as how to make conscious decisions about your own learning process to maximize positive outcomes.

Motivation for Learning

In the middle of the last century, experts held some odd beliefs that we might find exceptionally strange in our present age. For example, many scholars were convinced that not only was learning a passive activity, but that mass media such as movies, television, and newspapers held significant control over us as individuals. The thinking at that time was that we were helpless to think for ourselves or make choices about learning or the media we consumed. The idea was that we just simply ingested information fed to us and we were almost completely manipulated by it.

What changed this way of thinking was a significant study on audience motivations for watching different political television programs (Blumler & McQuail, 1969). The study found that not only did people make decisions about what information they consumed, but they also had preferences in content and how it was delivered. In other words, people were active in their choices about information. What is more important is that the research began to show that our own needs, goals, and personal opinions are bigger drivers for our choices in information than anything else. This gave rise to what became known as the Uses and Gratification Theory (UGT).

At first, personal choices about television programs might seem a strange topic for a chapter on learning, but if you think about it, learning at its simplest is the consumption of information to meet a specific need. You choose to learn something so you can attain certain goals. This makes education and UGT a natural fit.

Applying UGT to education is a learner-centered approach that focuses on helping you take control of how and what you learn. Not only that, but it gives you a framework as an informed learner and allows you to choose information and learning activities with the end results in mind. The next section examines UGT a little more closely and shows how it can be directly applied to learning.

The Uses and Gratification Model

The Uses and Gratification model is how people are thought to react according to UGT. It considers individual behavior and motivation as the primary driver for media consumption. In education this means that the needs of the learner are what determine the interaction with learning content such as textbooks, lectures, and other information sources. Since any educational program is essentially content and delivery (the same as with any media), the Uses and Gratification model can be applied to meet student needs, student satisfaction, and student academic success. This is something that is not recognized in many other learning theories since they begin with the premise that it is learning content and how it is delivered that influences the learner more than the learner’s own wants and expectations.

The main assumption of the Uses and Gratification model is that media consumers will seek out and return to specific media sources based on a personal need. For learners this is exceptionally useful since it gives an insight and the ability to positively influence their own motivations, expectations, and the perceived value of their education.

If you understand the key concepts of the Uses and Gratification model, you can make informed decisions about your own learning: how you learn, which materials you use to learn, and what motivates you to learn. An example of this is looking at how someone chooses to study for an exam, first reading the appropriate chapters, then making a list of chapter concepts and reviewing what was known, then returning to learn the information needed to fill the gaps. Each activity was chosen by the learner based on how well it fit their needs to help reach the goal of doing well on an exam.

Here we should offer a brief word of caution about being wary when choosing materials and media. There is a great deal of misleading and inaccurate information presented via the Internet and social media. Making informed decisions about your learning and the material you consume includes checking sources and avoiding information that is not credible.

In his book Key Themes in Media Theory, Laughey (2007) presents the UGT model according to its original authors as a single sentence that divides each area of influence into the following concerns:

- Social and psychological origins of …

- needs, which generate …

- expectations of …

- the mass media or other sources, which lead to …

- differential patterns of media exposure, resulting in …

- needs gratification and …

- other unintended consequences.

Taken as a list or a single sentence, this can be a bit overwhelming to digest. There are many things being said at the same time, and they may not all be immediately clear. To better understand what each of the “areas of concern” are and how they can impact learning, each has been separated and explained in the table below.

| Area of Concern | What it means for you | How it applies to learning | Real-world example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Social and psychological origins of … | Your motivations, not only as a student but as a person, and both the social and psychological factors that influence you | This can be everything from the original motivation behind enrolling in school in the first place, down to more specific goals like why you want to learn to write and communicate well. | A drive to be self-supporting and to take on a productive role in society. |

| 2. needs, which generate … | Better job, increased income, satisfying career, prestige | This can include the area of study you select and the school you choose to attend. | Pursuing a degree to seek a career in a field you enjoy. |

| 3. expectations of … | Expectation and perception (preconceived and continuing) of educational material | What you expect to learn to fulfill goals and meet needs. | Understanding what you need to accomplish the smaller goals. An example would be “study for an exam.” |

| 4. the mass media or other sources, which lead to… | The content and learning activities of the program | Selection of content aimed at fulfilling needs. Results are student satisfaction, perceived value, and continued enrollment. | Choosing which learning activities to use (e.g., texts, watch videos, research alternative content, etc.). |

| 5. differential patterns of media exposure, resulting in … | Frequency and level of participation | How you engage with learning activities and how often. Results are student satisfaction and perceived value, and continued enrollment. | When, how often, and how much time you spend in learning activities. |

| 6. needs gratification and … | Better job, increased income, satisfying career, prestige, more immediate goals like pass an exam, earn a good grade, etc. | Needs fulfillment and completion of goals. | Learning activities that meet your learning needs, including fulfillment of your original goals. |

| 7. other unintended consequences. | Increased skills and knowledge, entertainment, social involvement and networking | Causes positive loop-back into 4, 5, and 6, reinforcing those positive outcomes. | Things you learn beyond your initial goals. |

The UGT model asks you to reflect on the following questions:

- What is it that motivates you to learn something?

- What need does it fulfill?

- What do you expect to have happen with certain learning activities?

- How can you choose the right learning activities to better ensure you meet your needs and expectations?

- What other things might result from your choices?

Methods of Learning

Several decades ago, a new way of thinking about learning became very prominent in education. It was based on the concept that each person has a preferred way to learn. It was thought that these preferences had to do with each person’s natural tendencies toward one of their senses. The idea was that learning might be easier if a student sought out content that was specifically oriented to their favored sense. For example, it was thought that a student who preferred to learn visually would respond better to pictures and diagrams.

Over the years there were many variations on the basic idea, but one of the most popular theories was known as the VAK model. VAK was an acronym for the three types of learning, each linked to one of the basic senses thought to be used by students: visual, aural, and kinesthetic. What follows is an outline of each of these and the preferred method.

- Visual: The student prefers pictures, images, and the graphic display of information to learn. An example would be looking at an illustration that showed how to do something.

- Aural: The student prefers sound as a way to learn. Examples would be listening to a lecture or a podcast.

- Kinesthetic: The student prefers using their body, hands, and sense of touch. An example would be doing something physical, such as examining an object rather than reading about it or looking at an illustration.

In many ways these ideas about learning styles made some sense. Because of this, educators encouraged students to find out about their own learning styles. They developed tests and other techniques to help students determine which particular sense they preferred to use for learning, and in some cases learning materials were produced in multiple ways that focused on each of the different senses. That way, each individual learner could participate in learning activities that were tailored to their specific preferences.

While it initially seemed that dividing everyone by learning styles provided a leap forward in education, continued research began to show that the fixation on this new model might not have been as effective as it was once thought. In fact, in some cases, the way learning styles were actually being used created roadblocks to learning. This was because the popularization of this new idea brought on a rush to use learning styles in ways that failed to take into account several important aspects that are listed below:

- A person does not always prefer the same learning style all the time or for each situation. For example, some learners might enjoy lectures during the day but prefer reading in the evenings. Or they may prefer looking at diagrams when learning about mechanics but prefer reading for history topics.

- There are more preferences involved in learning than just the three that became popular. These other preferences can become nearly impossible to make use of within certain styles. For example, some prefer to learn in a more social environment that includes interaction with other learners. Reading can be difficult or restrictive as a group effort. Recognized learning styles beyond the original three include: social (preferring to learn as a part of group activity), solitary (preferring to learn alone or using self-study), or logical (preferring to use logic, reasoning, etc.).

- Students that thought they were limited to a single preferred learning style found themselves convinced that they could not do as well with content that was presented in a way that differed from their style (Pashler, McDaniel, Rohrer, & Bjork, 2009). For example, a student that had identified as a visual learner might feel they were at a significant disadvantage when listening to a lecture. Sometimes they even believed they had an even greater impairment that prevented them from learning that way at all.

- Some forms of learning are extremely difficult in activities delivered in one style or another. Subjects like computer programming would be almost impossible to learn using an aural learning style. And, while it is possible to read about a subject such as how to swing a bat or how to do a medical procedure, actually applying that knowledge in a learning environment is difficult if the subject is something that requires a physical skill.

Knowing and Taking Advantage of Learning in a Way That Works for You

The problem with relying on learning styles comes from thinking that just one defines your needs. Rather than being constrained by a single learning style, or limiting your activities to a certain kind of media, you may choose media that best fit your needs for what you are trying to learn at a particular time.

Following are a couple of ways you might combine your learning style preference with a given learning situation:

- You are trying to learn how to build something but find the written instructions confusing so you watch a video online that shows someone building the same thing.

- You have a long commute on the bus but reading while riding makes you dizzy. You choose an aural solution by listening to pre-recorded podcasts or a mobile device that reads your texts out loud.

These examples show that by recognizing and understanding what different learning styles have to offer, you can use the techniques that are best suited for you and that work best under the circumstances of the moment. You may also find yourself using two learning styles at the same time – as when you watch a live demonstration or video in which a person shows you how to do something while verbally explaining what you are being shown. This helps to reinforce the learning as it utilizes different aspects of your thinking. Using learning styles in an informed way can improve both the speed and the quality of your learning.

The Purpose of Learning Objectives

Using Bloom’s Taxonomy

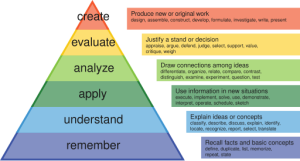

In 1956, Dr. Benjamin Bloom, an American educational psychologist who was particularly interested how people learn, chaired a committee of educators that developed and classified a set of learning objectives, which came to be known as Bloom’s taxonomy. This classification system has been updated a little since it was first developed, but it remains important for both students and teachers in helping to understand the skills and structures involved in learning.

Bloom’s taxonomy divides the cognitive domain of learning into six main learning-skill levels, or learning-skill stages, which are arranged hierarchically—moving from the simplest of functions like remembering and understanding, to more complex learning skills, like applying and analyzing, to the most complex skills—evaluating and creating. The lower levels are more straightforward and fundamental, and the higher levels are more sophisticated.

The following table describes the six main skillsets within the cognitive domain and gives you information on the level of learning expected for each. Read each description closely for details of what college-level work looks like in each domain (note that the table begins with remembering, the lowest level of the taxonomy).

| Main Skill Levels Within the Cognitive Domain | Description | Examples of Related Learning Skills (specific actions related to the skillset) |

|---|---|---|

| Remembering | When you are skilled in remembering, you can recognize or recall knowledge you’ve already gained, and you can use it to produce or retrieve definitions, facts, and lists. Remembering may be how you studied in grade school or high school, but college will require you to do more with the information. | identify · relate · list · define · recall · memorize · repeat · record · name |

| Understanding | Understanding is the ability to grasp or construct meaning from oral, written, and graphic messages. Each college course will introduce you to new concepts, terms, processes, and functions. Once you gain a firm understanding of new information, you’ll find it easier to comprehend how or why something works. | restate · locate · report · recognize · explain · express · identify · discuss · describe · review · infer · illustrate · interpret · draw · represent · differentiate · conclude |

| Applying | When you apply, you use or implement learned material in new and concrete situations. In college, you will be tested or assessed on what you’ve learned in the previous levels. You will be asked to solve problems in new situations by applying knowledge and skills in new ways. You may need to relate abstract ideas to practical situations. | apply · relate · develop · translate · use · operate · organize · employ · restructure · interpret · demonstrate · illustrate · practice · calculate · show · exhibit · dramatize |

| Analyzing | When you analyze, you have the ability to break down or distinguish the parts of material into its components, so that its organizational structure may be better understood. At this level, you will have a clearer sense that you comprehend the content well. You will be able to answer questions such as what if, or why, or how something would work. | analyze · compare · probe · inquire · examine · contrast · categorize · differentiate · contrast · investigate · detect · survey · classify · deduce · experiment · scrutinize · discover · inspect · dissect · discriminate · separate |

| Evaluating | With skills in evaluating, you are able to judge, check, and even critique the value of material for a given purpose. At this level in college, you will be able to think critically, Your understanding of a concept or discipline will be profound. You may need to present and defend opinions. | judge · assess · compare · evaluate · conclude · measure · deduce · argue · decide · choose · rate · select · estimate · validate · consider · appraise · value · criticize · infer |

| Creating | With skills in creating, you are able to put parts together to form a coherent or unique new whole. You can reorganize elements into a new pattern or structure through generating, planning, or producing. Creating requires originality and inventiveness. It brings together all levels of learning to theorize, design, and test new products, concepts, or functions. | compose · produce · design · assemble · create · prepare · predict · modify · plan · invent · formulate · collect · generalize · document combine · relate · propose · develop · arrange · construct · organize · originate · derive · write |

Reading and interpreting learning objectives is a metacognitive act, as the information can help you determine the level of learning expected of you and give you clues as to how you can prepare for assessment. For example, if your objective is to identify the parts of an atom, you should first recognize that being able to “identify” information falls within the domain of “remembering”; you will need to memorize the parts and be able to correctly label them. Flashcards, labeling a diagram, or drawing one yourself should be sufficient ways to prepare for your test. If, however, your objective is to calculate atomic mass, you will need to know not only the parts of the atom but also how to account for those parts to come up with the atomic mass; “calculate” falls within the domain of “applying,” which requires you to take information and use it to solve a problem in a new context.

Making Decisions about Your Own Learning

As a learner, the kinds of materials, study activities, and assignments that work best for you will derive from your own experiences and needs (needs that are both short-term as well as those that fulfill long-term goals). In order to make your learning better suited to meet these needs, you can use the knowledge you have gained about UGT and other learning theories to make decisions concerning your own learning. These decisions can include personal choices in learning materials, how and when you study, and most importantly, taking ownership of your learning activities as an active participant and decision maker. In fact, one of the main principles emphasized in this chapter is that students not only benefit from being involved in planning their instruction, but learners also gain by continually evaluating the actual success of that instruction. In other words: Does this work for me? Am I learning what I need to by doing it this way? While it may not always be possible to control every component of your learning over an entire degree program, you can take every opportunity to influence learning activities so they work to your best advantage.

Make Mistakes Safe

Create an environment for yourself where mistakes are safe and mistakes are expected as just another part of learning. The key is to allow yourself the opportunity to make mistakes and learn from them before they become a part of your grades. You can do this by creating your own learning activities that you design to do just that. An example of this might be taking practice quizzes on your own, outside of the more formal course activities. The quizzes could be something you find in your textbook, something you find online, or something that you develop with a partner. In the latter case you would arrange with a classmate for each of you to produce a quiz and then exchange them. That particular exercise would serve double learning duty, since to create a good quiz you would need to learn the main concepts of the subject, and answering the questions on your partner’s quiz might help you identify areas where you need more knowledge.

The main idea with this sort of practice is that you are creating a safe environment where you can make mistakes and learn from them before those mistakes can negatively impact your success in the course. Better to make mistakes on a practice run than on any kind of assignment or exam that can heavily influence your final grade in a course.

Make Everything Problem Centered

When working through a learning activity, the practical act of problem-solving is a good strategy. Problem-solving, as an approach, can give a learning activity more meaning and motivation for you, as a learner. Whenever possible it is to your advantage to turn an assignment or learning task into a problem you are trying to solve or something you are trying to accomplish.

In essence, you do this by deciding on some purpose for the assignment (other than just completing the assignment itself). An example of this would be taking the classic college term paper and writing it in a way that solves a problem you are already interested in.

Typically, many students treat a term paper as a collection of requirements that must be fulfilled—the paper must be on a certain topic; it should include an introduction section, a body, a closing, and a bibliography; it should be so many pages long, etc. With this approach, the student is simply completing a checklist of attributes and components dictated by the instructor, but other than that, there is no reason for the paper to exist.

Instead, writing it to solve a problem gives the paper purpose and meaning. For example, if you were to write a paper with the purpose of informing the reader about a topic they knew little about, that purpose would influence not only how you wrote the paper but would also help you make decisions on what information to include. It would also influence how you would structure information in the paper so that the reader might best learn what you were teaching them. Another example would be to write a paper to persuade the reader about a certain opinion or way of looking at things. In other words, your paper now has a purpose rather than just reporting facts on the subject. Obviously, you would still meet the format requirements of the paper, such as number of pages and inclusion of a bibliography, but now you do that in a way that helps to solve your problem.

Make It Occupation Related

Much like making assignments problem centered, you will also do well when your learning activities have meaning for your profession or major area of study. This can take the form of simply understanding how the things you are learning are important to your occupation, or it can include the decision to do assignments in a way that can be directly applied to your career. If an exercise seems pointless and possibly unrelated to your long-term goals, you will be much less motivated by the learning activity.

An example of understanding how a specific school topic impacts your occupation future would be that of a nursing student in an algebra course. At first, algebra might seem unrelated to the field of nursing, but if the nursing student recognizes that drug dosage calculations are critical to patient safety and that algebra can help them in that area, there is a much stronger motivation to learn the subject.

In the case of making a decision to apply assignments directly to your field, you can look for ways to use learning activities to build upon other areas or emulate tasks that would be required in your profession. Examples of this might be a communication student giving a presentation in a speech course on how the Internet has changed corporate advertising strategies, or an accounting student doing statistics research for an environmental studies course. Whenever possible, it is even better to use assignments to produce things that are much like what you will be doing in your chosen career. An example of this would be a graphic design student taking the opportunity to create an infographic or other supporting visual elements as a part of an assignment for another course. In cases where this is possible, it is always best to discuss your ideas with your instructor to make certain what you intend will still meet the requirements of the assignment.

Attributions

College Success Author: Amy Baldwin Provided by: OpenStax Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/college-success License: CC BY 4.0

Learning Framework: Effective Strategies for College Success. Author: Heather Syrett Provided by: Austin Community College Located at: https://oercommons.org/courseware/8434 License: CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

References

Blumler, J. G., & McQuail, D. (1969). Television in politics: Its uses and influence. University of Chicago Press.

Laughey, D. (2007). Key themes in media theory. Open University Press.

Pashler, H., McDaniel, M., Rohrer, D., & Bjork, R. (2009). Learning styles: Concepts and evidence. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9(3), 105-119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01038.x (Original work published 2008)