6.2 Thinking

Stevy Scarbrough

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this reading, you will be able to:

- Describe the planning, tracking, and assessing process of metacognition.

- Describe what critical thinking is and why it’s important.

- Identify logical fallacies and how to avoid them.

- Describe various ways to engage in creative thinking.

- Describe the process of problem-solving.

Remember the heavy “thinking” you did in high school? Most of it was recalling facts or information you had previously committed to memory. Perhaps in some courses you were asked to support a statement or hypothesis using content from your textbook or class. Your thinking in high school was very structured and tied closely to reflecting what was taught in class.

In college, you are expected to think for yourself; to access and evaluate new approaches and ideas; to contribute to your knowledge base; and to develop or create new, fresh ideas. You will be required to develop and use a variety of thinking skills—higher-order thinking skills—which you seldom used in high school. In college, your instructors’ roles will be not only to supply a base of new information and ideas, as good instructors will challenge you to stretch your skills and knowledge base through critical and creative thinking. Much of their teaching involves the questions they ask, not the directions they give. Your success in college education—and in life beyond college—is directly linked to becoming a better and more complete thinker. Becoming a better and more complete thinker requires mastering some skills and consistent practice.

What Is Thought?

“Cogito ergo sum.” This famous Latin phrase comes from French philosopher René Descartes in the early 1600s. Translated into English, it means “I think, therefore I am.” It’s actually a profound philosophical idea, and people have argued about it for centuries: we exist, and we are aware that we exist, because we think. Without thought or the ability to think, we don’t exist. Do you agree? Even if you think Descartes got it wrong, most would say that thought is intimately connected to being human and that, as humans, we are all thinking beings.

What, then, are thinking and thought? Below are some basic working definitions:

- Thinking is the mental process you use to form associations and models of the world. When you think, you manipulate information to form concepts, to engage in problem-solving, to reason, and to make decisions.

- Thought can be described as the act of thinking that produces thoughts, which arise as ideas, images, sounds, or even emotions.

Metacognition

While reading a difficult passage in a textbook on chemistry you recognize that you are not fully understanding the meaning of the section you just read or its connection to the rest of the chapter. This practice, thinking about how you think, is called metacognition. Students use metacognition when they practice self-awareness and self-assessment. You are the best judge of how well you know a topic or a skill. In college especially, thinking about your thinking is crucial so you know what you don’t know and how to fix this problem, i.e., what you need to study, how you need to organize your calendar, and so on.

If you stop and recognize this challenge with the aim of improving your comprehension, you are practicing metacognition. You may decide to highlight difficult terms to look up, write a summary of each paragraph in as few sentences as you can, or join a peer study group to work on your comprehension. If you know you retain material better if you hear it, you may read out loud or watch video tutorials covering the material. These are all examples of thinking about how you think and adapting your behavior based on this metacognition. Likewise, if you periodically assess your progress toward a goal, such as when you check your grades in a course every few weeks during the term so you know how well you are doing, this too is metacognition.

Beyond just being a good idea, thinking about your own thinking process allows you to reap great benefits from becoming more aware of and deliberate with your thoughts. If you know how you react in a specific thinking or learning situation, you have a better chance to improve how well you think or to change your thoughts altogether by tuning into your reaction and your thinking. You can plan how to move forward because you recognize the way you think about a task or idea makes a difference in what you do with that thought. Examine your thoughts and be aware of them.

Developmental psychiatrist John Flavell (1976) coined the term metacognition and divided the theory into three processes of planning, tracking, and assessing your own understanding. Using metacognition strategies before, during, and after reading, lectures, assignments, and group work can help improve your understanding of course material and help you be more successful in your courses.

Planning

Students can plan and get ready to learn by asking questions such as:

- What am I supposed to learn in this situation?

- What do I already know that might help me learn this information?

- How should I start to get the most out of this situation?

- What should I be looking for and anticipating as I read or study or listen?

As part of this planning stage, students may want to jot down the answers to some of the questions they considered while preparing to study. If the task is a writing assignment, prewriting is particularly helpful just to get your ideas down on paper. You may want to start an outline of ideas you think you may encounter in the upcoming session; it probably won’t be complete until you learn more, but it can be a place to start.

Tracking

Students can keep up with their learning or track their progress by asking themselves:

- How am I doing so far?

- What information is important in each section?

- Should I slow down my pace to understand the difficult parts more fully?

- What information should I review now or mark for later review?

In this part of metacognition, students may want to step away from a reading selection and write a summary paragraph on what the passage was about without looking at the text. Another way to track your learning progress is to review lecture or lab notes within a few hours of the initial note-taking session. This allows you to have a fresh memory of the information and fill in gaps you may need to research more fully.

Assessing

Students can assess their learning by asking themselves:

- How well do I understand this material?

- What else can I do to understand the information better?

- Is there any element of the task I don’t get yet?

- What do I need to do now to understand the information more fully?

- How can I adjust how I study (or read or listen or perform) to get better results moving forward?

Looking back at how you did on assignments, tests, and reading selections isn’t just a means to getting a better grade the next time, even if that does sometimes happen as a result of this sort of reflection. If you rework the math problems you missed on a quiz and figure out what went wrong the first time, you will understand that mathematical concept better than if you ignore the opportunity to learn from your errors. Learning is not a linear process; you will bring knowledge from other parts of your life and from your reading to understand something new in your academic or personal learning for the rest of your life. Using these planning, tracking, and assessing strategies will help you progress as a learner in all subjects.

Critical Thinking

As a college student, you are tasked with engaging and expanding your thinking skills. One of the most important of these skills is critical thinking because it relates to nearly all tasks, situations, topics, careers, environments, challenges, and opportunities. It is a “domain-general” thinking skill, not one that is specific to a particular subject area. Critical thinking is the ability to discover the value of an idea, a set of beliefs, a claim, or an argument. It is a foundation for effective communication, the principal skill used in effective decision making, at the core of creating new knowledge, a way to uncover bias and prejudices. It requires you to use logic to evaluate evidence or information to make a decision or reach a conclusion. The word logic comes from the Ancient Greek logike, referring to the science or art of reasoning. Using logic, a person evaluates arguments and reasoning and strives to distinguish between good and bad reasoning, or between truth and falsehood. Using logic, you can evaluate the ideas and claims of others, make good decisions, and form sound beliefs about the world.

|

Critical Thinking IS |

Critical Thinking is NOT |

|---|---|

|

Questioning |

Passively accepting |

|

Skepticism |

Memorizing |

|

Challenging reasoning |

Group thinking |

|

Examining assumptions |

Blind acceptance of authority |

|

Uncovering biases |

Following conventional thinking |

Engaging in Critical Thinking

The critical thinking process is really nothing more than asking the right questions to understand a problem or issue and then gathering the data you need to complete the decision or take sides on an issue.

What is the problem or issue I am considering really about? Understanding this is key to successful critical thinking. What is the objective? A position? A decision? Are you deciding what candidate in an election will do a better overall job, or are you looking to strengthen the political support for a particular cause? Are you really against a recommendation from your dad, or are you using the issue to establish your independence?

Do you understand the terms related to the issue? Are you in agreement with the proponent’s definitions? For example, if you are evaluating a quotation on the health-care system for use in a paper, your objective might be to decide to use the quotation or not, but before you can make that decision you need to understand what the writer is really saying. If a term like “family” is used, for example, does it mean direct relations or extended family?

What are my options? What are choices that are available to you (if you are making a decision), or what are the “sides” (in the case of a position) you might choose to agree with? What are their differences? What are the likely consequences of each option? In making a decision, it might be helpful to ask yourself, “What is the worst thing that might happen in each scenario?” Examining different points of view is very important; there may be dozens of alternative viewpoints to a particular issue—and the validity of each can change depending on circumstances. A position that is popular or politically correct today may not have been a year ago, and there is no guarantee it will be right in the future. Likewise, a solution to a personal problem that was successful for your roommate may not apply to you. Remember also that sometimes the best option might be a combination of the options you identify initially.

What do I know about each option? First, make sure you have all the information about each option. Do you have all the information to support each of your likely options? What is still missing? Where can you get the information you need? Keep an open mind and don’t dismiss supporting information on any position before you evaluate it carefully.

How good is my information? Now it’s time to evaluate the quality of the support of each option or point of view. Evaluate the strengths and the weaknesses of each piece of supporting evidence. Are all the relevant facts presented? Are some facts presented in misleading ways? Are enough examples presented to support the premise? Consider the source of the supporting information. Who is the expert presenting the facts? That “expert” may have a vested interest in the position. Consider that bias, more for understanding the point of view than for rejecting it. Consider your own opinions (especially when working with emotional issues); are your emotional ties to a point of view getting in your way of clear thinking (your own biases)? If you really like a particular car model, are you giving the financial implications of buying that car a fair consideration? Are there any errors or fallacies in your logic?

Fallacies are defects in logic that weaken arguments. You should learn to identify them in your own thinking so you can strengthen your positions, as well as in the arguments of others when evaluating their strength.

| Fallacy | Description | Examples | How to Avoid it in Your Own Thinking |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalizations | Making assumptions about a whole group of people based on an inadequate sample | Engineering students are nerds.

My economics class is boring, and my friend says her economics class is boring, too—therefore all economics classes are boring. |

What kind of sample are you using? Is it large enough to support the conclusions? You may want to increase your sample size or draw a more modest conclusion by using the word “some” or “many.” |

| Post Hoc/False Clause | Drawing improper conclusions through sequencing. If A comes before B, then A causes B. | I studied biology last term, and this term I’m taking organic chem, which is very confusing. Biology makes chemistry confusing. | When making causal statements, be sure you can explain the process through which A causes B beyond their mere sequence. |

| Ad hominem | Attacking the character of the person making an argument, rather than the merits of the argument. Common in political arguments. | I won’t support Senator Smith’s education bill. He’s had a mistress and marital problems. | Focus on the merits and supporting data of an argument, not on the personality or behavior of the people making the arguments. |

| Bandwagon Appeal/Ad populum | Justifying an issue based solely on the number of people involved. | A parent explains the evidence of the risks of binge drinking. The child rejects the arguments, saying, “When you were my age, you drank too.”

It’s healthy to drink soda; millions of American kids do. |

The popular position is not always the right one. Be wary of arguments that rely exclusively on one set of numbers. |

| Appealing to Authority | Using an endorsement from someone as a primary reason for supporting a point of view. | We should oppose higher taxes; Curt Schilling does.

Pitcher Curt Schilling may be a credible authority on baseball, but is he an authority on taxes? |

Quoting authorities is a valuable tool to build an argument; make sure the authorities you quote are truly subject matter experts on the issue you are discussing. |

| False Dichotomy | Setting up a situation in which it looks like there are only two possible options. If one option is discredited, the other must be accepted. | If you don’t like cats, you must hate animals. | Examine your own thinking. Are there really only two options? Look for the third option. If you were asked to develop a compromise between the two positions, what would it look like? What would its strengths and weaknesses be? |

| Red herring | Avoids addressing the actual argument through diversion or misdirection using an irrelevant issue | When someone is pulled over for running a red light and asks the officer why they aren’t out arresting drunk drivers instead.

When a politician is asked for their position on a topic and the politician describes how much they love their country, rather than answering the question they were asked. |

Think about what you are being asked and give a response that is relevant to the question. |

| Straw Man | Distorting an argument by oversimplifying, exaggerating, taking it out of context, or only focusing on part of it, then arguing against that. | Person 1: “I think we need to get a video doorbell since our packages keep getting stolen.”

Person 2: “So you don’t trust your neighbors?” |

When thinking about an argument being made, you can restate the argument to make sure you understand, then provide your counterpoint. |

Creative Thinking

Creative thinking is the ability to look at things from a new perspective, to come up with fresh solutions to problems. It is a deliberate process that allows you to think in ways that improve the likelihood of generating new ideas or thoughts.

Let’s start by killing a couple of myths:

- Creativity is an inherited skill. Creativity is not something people are born with but is a skill that is developed over time with consistent practice. It can be argued that people you think were “born” creative because their parents were creative, too, are creative simply because they have been practicing creative thinking since childhood, stimulated by their parents’ questions and discussions.

- Creativity is free-form thinking. While you may want to free yourself from all preconceived notions, there is a recognizable structure to creative thinking. Rules and requirements do not limit creative thinking—they provide the scaffolding on which truly creative solutions can be built. Free-form thinking often lacks direction or an objective; creative thinking is aimed at producing a defined outcome or solution.

Creative thinking involves coming up with new or original ideas; it is the process of seeing the same things others see but seeing them differently. You use skills such as examining associations and relationships, flexibility, elaboration, modification, imagery, and metaphorical thinking. In the process, you will stimulate your curiosity, come up with new approaches to things, and have fun!

Tips for Creative Thinking

- Feed your curiosity. Read. Read books, newspapers, magazines, blogs—anything at any time. When surfing the Web, follow links just to see where they will take you. Go to the theatre or movies. Attend lectures. Creative people make a habit of gathering information, because they never know when they might put it to good use. Creativity is often as much about rearranging known ideas as it is about creating a completely new concept. The more “known ideas” you have been exposed to, the more options you’ll have for combining them into new concepts.

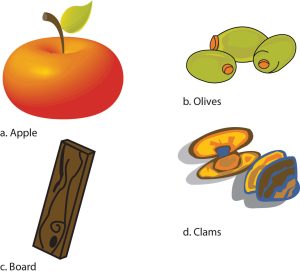

- Develop your flexibility by looking for a second right answer. Throughout school we have been conditioned to come up with the right answer; the reality is that there is often more than one “right” answer. Examine all the possibilities. Look at the items in Figure 6.4 below. Which is different from all the others?

If you chose C, you’re right; you can’t eat a board. Maybe you chose D; that’s right, too—clams are the only animal on the chart. B is right, as it’s the only item you can make oil from, and A can also be right; it’s the only red item.

Each option can be right depending on your point of view. Life is full of multiple answers, and if we go along with only the first most obvious answer, we are in danger of losing the context for our ideas. The value of an idea can only be determined by comparing it with another. Multiple ideas will also help you generate new approaches by combining elements from a variety of “right” answers. In fact, the greatest danger to creative thinking is to have only one idea. Always ask yourself, “What’s the other right answer?”

- Combine old ideas in new ways. When King C. Gillette registered his patent for the safety razor, he built on the idea of disposable bottle caps, but his venture didn’t become profitable until he toyed with a watch spring and came up with the idea of how to manufacture inexpensive (therefore disposable) blades. Bottle caps and watch springs are far from men’s grooming materials, but Gillette’s genius was in combining those existing but unlikely ideas. Train yourself to think “out of the box.” Ask yourself questions like, “What is the most ridiculous solution I can come up with for this problem?” or “If I were transported by a time machine back to the 1930s, how would I solve this problem?” You may enjoy watching competitive design, cooking, or fashion shows (Top Chef, Chopped, Project Runway, etc.); they are great examples of combining old ideas to make new, functional ones.

- Think metaphorically. Metaphors are useful to describe complex ideas; they are also useful in making problems more familiar and in stimulating possible solutions. For example, if you were a partner in a company about to take on outside investors, you might use the pie metaphor to clarify your options (a smaller slice of a bigger pie versus a larger slice of a smaller pie). If an organization you are a part of is lacking direction, you may search for a “steady hand at the tiller,” communicating quickly that you want a consistent, nonreactionary, calm leader. Based on that ship-steering metaphor, it will be easier to see which of your potential leaders you might want to support. Your ability to work comfortably with metaphors takes practice. When faced with a problem, take time to think about metaphors to describe it, and the desired solution. Observe how metaphors are used throughout communication and think about why those metaphors are effective. Have you ever noticed that the financial business uses water-based metaphors (cash flow, frozen assets, liquidity) and that meteorologists use war terms (fronts, wind force, storm surge)? What kinds of metaphors are used in your area of study?

- Ask. A creative thinker always questions the way things are: Why are we doing things this way? What were the objectives of this process and the assumptions made when we developed the process? Are they still valid? What if we changed certain aspects? What if our circumstances changed? Would we need to change the process? How? Get in the habit of asking questions—lots of questions.

Problem Solving

Much of your college and professional life will be spent solving problems; some will be complex, such as deciding on a career, and require time and effort to come up with a solution. Others will be small, such as deciding what to eat for lunch, and will allow you to make a quick decision based entirely on your own experience. But, in either case, when coming up with the solution and deciding what to do, follow the same basic steps.

- Define the problem. Use your analytical skills. What is the real issue? Why is it a problem? What are the root causes? What kinds of outcomes or actions do you expect to generate to solve the problem? What are some of the key characteristics that will make a good choice: Timing? Resources? Availability of tools and materials? For more complex problems, it helps to actually write out the problem and the answers to these questions. Can you clarify your understanding of the problem by using metaphors to illustrate the issue?

- Narrow the problem. Many problems are made up of a series of smaller problems, each requiring its own solution. Can you break the problem into different facets? What aspects of the current issue are “noise” that should not be considered in the problem solution? (Use critical thinking to separate facts from opinion in this step.)

- Generate possible solutions. List all your options. Use your creative thinking skills in this phase. Did you come up with the second “right” answer, and the third or the fourth? Can any of these answers be combined into a stronger solution? What past or existing solutions can be adapted or combined to solve this problem?

- Choose the best solution. Use your critical thinking skills to select the most likely choices. List the pros and cons for each of your selections. How do these lists compare with the requirements you identified when you defined the problem? If you still can’t decide between options, you may want to seek further input from your brainstorming team

Attributions

College Success Author: Amy Baldwin Provided by: OpenStax Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/college-success License: CC BY 4.0

College Success. Provided by: Saylor Academy Located at: https://saylordotorg.github.io/text_college-success/index.html License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0

References

Flavell, J. H. (1976). Metacognitive aspects of problem solving. In L. B. Resnick (Ed.), The nature of intelligence (pp. 231–236). Hillsdale, NJ:

ErlbaumFriedman, T. L. (2008, December 23). Time to reboot America. New York Times. Retrieved April 7, 2025 from http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/24/opinion/24friedman.html?_r=2