7.1 Active Reading

Stevy Scarbrough

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this reading, you will be able to:

- Explain how reading in college is different from reading in high school.

- Identify common types of reading tasks assigned in a college class.

- Describe the purpose and instructor expectations of academic reading.

- Identify effective reading strategies for academic texts using the SQ3R System.

- Describe strategies to help you read effectively.

- Identify vocabulary-building techniques to strengthen your reading comprehension.

Think back to a high school history or literature class. Those were probably the classes in which you had the most reading. You would be assigned a chapter, or a few pages in a chapter, with the expectation that you would be discussing the reading assignment in class. In class, the teacher would guide you and your classmates through a review of your reading and ask questions to keep the discussion moving. The teacher usually was a key part of how you learned from your reading.

If you have been away from school for some time, it’s likely that your reading has been fairly casual. While time spent with a magazine or newspaper can be important, it’s not the sort of concentrated reading you will do in college. And no one will ask you to write in response to a magazine piece you’ve read or quiz you about a newspaper article.

College Reading Expectations

In college, reading is much different. You will be expected to read much more. For each hour you spend in the classroom, you will be expected to spend two or more additional hours studying between classes, and most of that will be reading. Assignments will be longer (a couple of chapters is common, compared with perhaps only a few pages in high school) and much more difficult. College textbook authors write using many technical terms and include complex ideas. Many college authors include research, and some textbooks are written in a style you may find very dry. You will also have to read from a variety of sources: your textbook, ancillary materials, primary sources, academic journals, periodicals, and online postings. Your assignments in literature courses will be complete books, possibly with convoluted plots and unusual wording or dialects, and they may have so many characters you’ll feel like you need a scorecard to keep them straight.

In college, most instructors do not spend much time reviewing the reading assignment in class. Rather, they expect that you have done the assignment before coming to class and understand the material. The class lecture or discussion is often based on that expectation. Tests, too, are based on that expectation. This is why active reading is so important—it’s up to you to do the reading and comprehend what you read.

Types Of College Reading Materials

As a college student, you will eventually choose a major or focus of study. In your first year or so, though, you’ll probably have to complete “core” or required classes in different subjects. For example, even if you plan to major in English, you may still have to take at least one science, history, and math class. These different academic disciplines (and the instructors who teach them) can vary greatly in terms of the materials that students are assigned to read. Not all college reading is the same. So, what types can you expect to encounter?

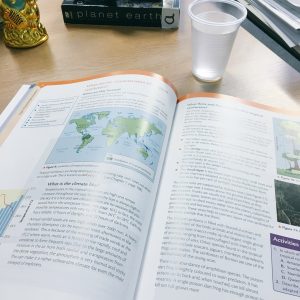

Textbooks

Probably the most familiar reading material in college is the textbook. These are academic books, usually focused on one discipline, and their primary purpose is to educate readers on a particular subject; ”Principles of Algebra,” for example, or “Introduction to Business.” It’s not uncommon for instructors to use one textbook as the primary text for an entire course. Instructors typically assign chapters as readings and may include any word problems or questions in the textbook, too.

Articles

Instructors may also assign academic/peer reviewed articles or news articles. Academic articles are written by people who specialize in a particular field or subject, while news articles may be from recent newspapers and magazines. For example, in a science class, you may be asked to read an academic article on the benefits of rainforest preservation, whereas in a government class, you may be asked to read an article summarizing a recent presidential debate. Instructors may have you read the articles online or they may distribute copies in class or electronically.

The chief difference between news and academic articles is the intended audience of the publication. News articles are mass media: They are written for a broad audience, and they are published in magazines and newspapers that are generally available for purchase at grocery stores or bookstores. They may also be available online. Academic articles, on the other hand, are usually published in scholarly journals with fairly small circulations. While you won’t be able to purchase individual journal issues from Barnes and Noble, public and school libraries do make these journal issues and individual articles available. It’s common to access academic articles through online databases hosted by libraries.

Literature and Nonfiction Books

Instructors use literature and nonfiction books in their classes to teach students about different genres, events, time periods, and perspectives. For example, a history instructor might ask you to read the diary of a girl who lived during the Great Depression so you can learn what life was like back then. In an English class, your instructor might assign a series of short stories written during the 1960s by different American authors, so you can compare styles and thematic concerns.

Literature includes short stories, novels or novellas, graphic novels, drama, and poetry. Nonfiction works include creative nonfiction—narrative stories told from real life—as well as history, biography, and reference materials. Textbooks and scholarly articles are specific types of nonfiction; often their purpose is to instruct, whereas other forms of nonfiction are written to inform, to persuade, or to entertain.

Purpose Of Academic Reading

Casual reading across genres, from books and magazines to newspapers and blogs, is something students should be encouraged to do in their free time because it can be both educational and fun. In college, however, instructors generally expect students to read resources that have particular value in the context of a course. Why is academic reading beneficial?

- Information comes from reputable sources: Web sites and blogs can be a source of insight and information, but not all are useful as academic resources. They may be written by people or companies whose main purpose is to share an opinion or sell you something. Academic sources such as textbooks and scholarly journal articles, on the other hand, are usually written by experts in the field and have to pass stringent peer review requirements in order to get published.

- Learn how to form arguments: In most college classes except for creative writing, when instructors ask you to write a paper, they expect it to be argumentative in style. This means that the goal of the paper is to research a topic and develop an argument about it using evidence and facts to support your position. Since many college reading assignments (especially journal articles) are written in a similar style, you’ll gain experience studying their strategies and learning to emulate them.

- Exposure to different viewpoints: One purpose of assigned academic readings is to give students exposure to different viewpoints and ideas. For example, in an ethics class, you might be asked to read a series of articles written by medical professionals and religious leaders who are pro-life or pro-choice and consider the validity of their arguments. Such experience can help you wrestle with ideas and beliefs in new ways and develop a better understanding of how others’ views differ from your own.

Active Learning When Reading

Many instructors conduct their classes mainly through lectures. The lecture remains the most pervasive teaching format across the field of higher education. One reason is that the lecture is an efficient way for the instructor to control the content, organization, and pace of a presentation, particularly in a large group. However, there are drawbacks to this “information-transfer” approach, where the instructor does all the talking and the students quietly listen: students have a hard time paying attention from start to finish; the mind wanders. Also, current cognitive science research shows that adult learners need an opportunity to practice newfound skills and newly introduced content. Lectures can set the stage for that interaction or practice, but lectures alone don’t foster student mastery. While instructors typically speak 100–200 words per minute, students hear only 50–100 of them. Moreover, studies show that students retain 70 percent of what they hear during the first ten minutes of class and only 20 percent of what they hear during the last ten minutes of class.

Thus it is especially important for students in lecture-based courses to engage in active learning outside of the classroom. But it’s also true for other kinds of college courses—including the ones that have active learning opportunities in class. Why? Because college students spend more time working (and learning) independently and less time in the classroom with the instructor and peers. Also, much of one’s coursework consists of reading and writing assignments. How can these learning activities be active? The following are very effective strategies to help you be more engaged with, and get more out of, the learning you do outside the classroom:

- Write in your books: You can underline and circle key terms, or write questions and comments in the margins of their books. The writing serves as a visual aid for studying and makes it easier for you to remember what you’ve read or what you’d like to discuss in class. If you are borrowing a book or want to keep it unmarked so you can resell it later, try writing keywords and notes on Post-its and sticking them on the relevant pages.

- Annotate a text: Annotations typically mean writing a brief summary of a text and recording the works-cited information (title, author, publisher, etc.). This is a great way to “digest” and evaluate the sources you’re collecting for a research paper, but it’s also invaluable for shorter assignments and texts since it requires you to actively think and write about what you read.

- Create mind maps: Mind maps are effective visuals tools for students, as they highlight the main points of readings or lessons. Think of a mind map as an outline with more graphics than words. For example, if a student were reading an article about America’s First Ladies, they might write, “First Ladies” in a large circle in the center of a piece of paper. Connected to the middle circle would be lines or arrows leading to smaller circles with visual representations of the women discussed in the article. Then, these circles might branch out to even smaller circles containing the attributes of each of these women.

In addition to the strategies described above, the following are additional ways to engage in active reading and learning:

- Work when you are fully awake, and give yourself enough time to read a text more than once.

- Read with a pen or highlighter in hand, and underline or highlight significant ideas as you read.

- Interact with the ideas in the margins (summarize ideas; ask questions; paraphrase difficult sentences; make personal connections; answer questions asked earlier; challenge the author; etc.).

- As you read, keep the following in mind:

- What is the CONTEXT in which this text was written? (This writing contributes to what topic, discussion, or controversy? Context is bigger than this one written text.)

- Who is the intended AUDIENCE? (There’s often more than one intended audience.)

- What is the author’s PURPOSE? To entertain? To explain? To persuade? (There’s usually more than one purpose, and essays almost always have an element of persuasion.)

- How is this writing ORGANIZED? Compare and contrast? Classification? Chronological? Cause and effect? (There’s often more than one organizational form.)

- What is the author’s TONE? (What are the emotions behind the words? Are there places where the tone changes or shifts?)

- What TOOLS does the author use to accomplish her/his purpose? Facts and figures? Direct quotations? Fallacies in logic? Personal experience? Repetition? Sarcasm? Humor? Brevity?

- What is the author’s THESIS—the main argument or idea, condensed into one or two sentences?

- Foster an attitude of intellectual curiosity. You might not love all of the writing you’re asked to read and analyze, but you should have something interesting to say about it, even if that “something” is critical.

Reading Strategies For Academic Texts

Recall from the Active Learning section that effective reading requires more engagement than just reading the words on the page. In order to learn and retain what you read, it’s a good idea to do things like circling keywords, writing notes, and reflecting. Actively reading academic texts can be challenging for students who are used to reading for entertainment alone, but practicing the following steps will get you up to speed.

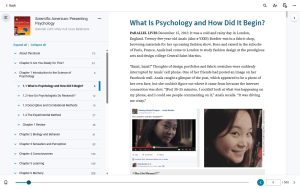

SQ3R

SQ3R is a reading comprehension method named for its five steps: Survey, Question, Read, Recite, and Review. The method was introduced by Francis Pleasant Robinson, an American education philosopher in his 1946 book Effective Study.

The method offers an efficient and active approach to reading textbook material. It was created for college students but is extremely useful in a variety of situations. Classrooms all over the world have begun using this method to better understand what they’re reading.

- Survey –You can gain insight from an academic text before you even begin the reading assignment. For example, if you are assigned a nonfiction book, read the title, the back of the book, and table of contents. Scanning this information can give you an initial idea of what you’ll be reading and some useful context for thinking about it. You can also start to make connections between the new reading and the knowledge you already have, which is another strategy for retaining information. Survey the document by scanning its contents, gathering the necessary information to focus on topics, and help set study goals.

- Read the title, introduction, summary, or a chapter’s first paragraph(s). This helps to orient yourself to how this chapter is organized and to understand the topic’s key points.

- Go through each boldface heading and subheading. This will help you to create a mental structure for the topic.

- Check all graphics and captions closely. They’re there to emphasize certain points and provide rich additional information.

- Check reading aids and any footnotes. Emphasized text (italics, bold font, etc.) is typically introduced to catch the reader’s attention or to provide clarification.

- Question – During this stage, you should note any questions on the subjects contained in the document. It is helpful to survey the textbook again, this time writing down the questions that you create while scanning each section. You can easily find what questions need to be answered by looking at the Learning Objectives at the beginning of a chapter, the headings, and sub-headings within the chapter and the Chapter Summary or Key Points at the end of a chapter. These questions become study goals and they will become information you’ll actively search later on while going through each section in detail.

- Write your questions down so you can fill in the answers as you read.

- Make sure to answer the questions in your own words, rather than copying directly from the text.

- Read – Read each section thoroughly, keeping your questions in mind. Try to find the answers and identify if you need additional ones. Mind Mapping can probably help to make sense of and correlate all the information.

- Recall/Recite – In the recall (or recite) stage, you should go through what you read and try to answer the questions you noted before. Check-in after every section, chapter, or topic to make sure you understand the material and can explain it, in your own words. It’s worth taking the time to write a short summary, even if your instructor doesn’t require it. The exercise of jotting down a few sentences or a short paragraph capturing the main ideas of the reading is enormously beneficial: it not only helps you understand and absorb what you read but gives you ready study and review materials for exams and other writing assignments. Pretend you are responsible for teaching this section to someone else. Can you do it? It’s at this stage that you consolidate knowledge, so refrain from moving on until you can recall the core information.

- Review – Reviewing all the collected information is the final step of the process. In this stage, you can review the collected information, go through any particular chapter, expand your own notes, or discuss the topics with colleagues and other experts. An excellent way to consolidate information is to present or teach it to someone else. It always helps to revisit what you’ve read for a quick refresher. Before class discussions or tests, it’s a good idea to review your questions, summaries, and any other notes you have taken.

Additional Strategies for Textbook Reading

The SQ3R system provides a proven approach to effective learning from texts. Following are some strategies you can use to enhance your reading even further:

- Pace yourself. Figure out how much time you have to complete the assignment. Divide the assignment into smaller blocks rather than trying to read the entire assignment in one sitting. If you have a week to do the assignment, for example, divide the work into five daily blocks, not seven; that way you won’t be behind if something comes up to prevent you from doing your work on a given day. If everything works out on schedule, you’ll end up with an extra day for review.

- Schedule your reading. Set aside blocks of time, preferably at the time of the day when you are most alert, to do your reading assignments. Don’t just leave them for the end of the day after completing written and other assignments.

- Get yourself in the right space. Choose to read in a quiet, well-lit space. Your chair should be comfortable but provide good support. Libraries were designed for reading—they should be your first option! Don’t use your bed for reading textbooks; since the time you were read bedtime stories, you have probably associated reading in bed with preparation for sleeping. The combination of the cozy bed, comforting memories, and dry text are sure to invite some shut-eye!

- Avoid distractions. Active reading takes place in your short-term memory. Every time you move from task to task, you have to “reboot” your short-term memory and you lose the continuity of active reading. Multitasking—listening to music or texting on your cell while you read—will cause you to lose your place and force you to start over again. Every time you lose focus, you cut your effectiveness and increase the amount of time you need to complete the assignment.

- Avoid reading fatigue. Work for about fifty minutes, and then give yourself a break for five to ten minutes. Put down the book, walk around, get a snack, stretch, or do some deep knee bends. Short physical activity will do wonders to help you feel refreshed.

- Read your most difficult assignments early in your reading time, when you are freshest.

- Make your reading interesting. Try connecting the material you are reading with your class lectures or with other chapters. Ask yourself where you disagree with the author. Approach finding answers to your questions like an investigative reporter. Carry on a mental conversation with the author.

- Highlight your reading material. Most readers tend to highlight too much, hiding key ideas in a sea of yellow lines, making it difficult to pick out the main points when it is time to review. When it comes to highlighting, less is more. Think critically before you highlight. Your choices will have a big impact on what you study and learn for the course. Make it your objective to highlight no more than 15-25% of what you read. Use highlighting after you have read a section to note the most important points, key terms, and concepts. You can’t know what the most important thing is unless you’ve read the whole section, so don’t highlight as you read.

- Annotate your reading material. Marking up your book may go against what you were told in high school when the school owned the books and expected to use them year after year. In college, you bought the book. Make it truly yours. Although some students may tell you that you can get more cash by selling a used book that is not marked up, this should not be a concern at this time—that’s not nearly as important as understanding the reading and doing well in the class! The purpose of marking your textbook is to make it your personal studying assistant with the key ideas called out in the text. Use your pencil also to make annotations in the margin. Use a symbol like an exclamation mark (!) or an asterisk (*) to mark an idea that is particularly important. Use a question mark (?) to indicate something you don’t understand or are unclear about. Box new words, then write a short definition in the margin. Use “TQ” (for “test question”) or some other shorthand or symbol to signal key things that may appear in test or quiz questions. Write personal notes on items where you disagree with the author. Don’t feel you have to use the symbols listed here; create your own if you want, but be consistent. Your notes won’t help you if the first question you later have is “I wonder what I meant by that?”

- Get to Know the Conventions. Academic texts, like scientific studies and journal articles, may have sections that are new to you. If you’re not sure what an “abstract” is, research it online or ask your instructor. Understanding the meaning and purpose of such conventions is not only helpful for reading comprehension but for writing, too.

- Look up and Keep Track of Unfamiliar Terms and Phrases. Have a good college dictionary such as Merriam-Webster handy (or find it online) when you read complex academic texts, so you can look up the meaning of unfamiliar words and terms. Many textbooks also contain glossaries or “key terms” sections at the ends of chapters or the end of the book. If you can’t find the words you’re looking for in a standard dictionary, you may need one specially written for a particular discipline. For example, a medical dictionary would be a good resource for a course in anatomy and physiology. If you circle or underline terms and phrases that appear repeatedly, you’ll have a visual reminder to review and learn them. Repetition helps to lock in these new words and their meaning get them into long-term memory, so the more you review them the more you’ll understand and feel comfortable using them.

- Make Flashcards. If you are studying certain words for a test, or you know that certain phrases will be used frequently in a course or field, try making flashcards for review. For each key term, write the word on one side of an index card and the definition on the other. Drill yourself, and then ask your friends to help quiz you. Developing a strong vocabulary is similar to most hobbies and activities. Even experts in a field continue to encounter and adopt new words. The following video discusses more strategies for improving vocabulary.

Online Texts

Reading online texts presents unique challenges for some students. For one thing, you can’t readily circle or underline key terms or passages on the screen with a pencil. For another, there can be many tempting distractions while reading online – just a quick visit to social media sites or to check your email.

While there’s no substitute for old-fashioned self-discipline, you can take advantage of the following tips to make online reading more efficient and effective:

- Get a browser extension that allows you to highlight and annotate your online text.

- If possible, download the reading as a PDF, Word document, etc., so you can read it offline.

- Get an app or browser extension that disables your social media sites for specified periods of time.

- Adjust your screen to avoid glare and eye strain, and change the text font to be less distracting (for those essays written in Comic Sans).

- Follow the SQ3R system, taking notes and answering questions as you go. Since highlighting and annotating are more difficult with online texts, it is imperative that you take quality notes.

- Look for reputable online sources. Professors tend to assign reading from reputable print and online sources, so you can feel comfortable referencing such sources in class and for writing assignments. If you are looking for online sources independently, however, devote some time and energy to critically evaluating the quality of the source before spending time reading any resources you find there. Find out what you can about the author (if one is listed), the Website, and any affiliated sponsors it may have. Check that the information is current and accurate against similar information on other pages. Depending on what you are researching, sites that end in “.edu” (indicating an “education” site such as a college, university, or other academic institution) tend to be more reliable than “.com” sites. Check with a librarian for help in identifying reputable online sources.

Building Your Vocabulary

Gaining confidence with the unique terminology used in different disciplines can help you be more successful in your courses and in college generally. A good vocabulary is essential for success in any role that involves communication, and just about every role in life requires good communication skills. We include this section on vocabulary in this chapter on reading because of the connections between vocabulary building and reading. Building your vocabulary will make your reading easier, and reading is the best way to build your vocabulary.

Learning new words can be fun and does not need to involve tedious rote memorization of word lists. The first step, as with any other aspect of the learning cycle, is to prepare yourself to learn. Consciously decide that you want to improve your vocabulary; decide you want to be a student of words. Work to become more aware of the words around you: the words you hear, the words you read, the words you say, and those you write.

In addition to the suggestions described earlier, such as looking up unfamiliar words in dictionaries, the following are additional vocabulary-building techniques for you to try:

- Read everything and read often. Reading frequently both in and out of the classroom will help strengthen your vocabulary. Whenever you read a book, magazine, newspaper, blog, or any other resource, keep a running list of words you don’t know. Look up the words as you encounter them and try to incorporate them into your own speaking and writing.

- Be on the lookout for new words. Most will come to you as you read, but they may also appear in an instructor’s lecture, a class discussion, or a casual conversation with a friend. They may pop up in random places like billboards, menus, or even online ads!

- Write down the new words you encounter, along with the sentences in which they were used. Do this in your notes with new words from a class or reading assignment. If a new word does not come from a class, you can write it on just about anything, but make sure you write it. Many word lovers carry a small notepad or a stack of index cards specifically for this purpose.

- Infer the meaning of the word. The context in which the word is used may give you a good clue about its meaning. Do you recognize a common word root in the word? What do you think it means?

- Look up the word in a dictionary. Do this as soon as possible (but only after inferring the meaning). When you are reading, you should have a dictionary at hand for this purpose. In other situations, do this within a couple hours, definitely during the same day. How does the dictionary definition compare with what you inferred? Install a reliable dictionary app on your phone or computer. Look for ones that also pronounce the word.

- Make connections to words you already know. You may be familiar with the “looks like . . . sounds like” saying that applies to words. It means that you can sometimes look at a new word and guess the definition based on similar words whose meaning you know. For example, if you are reading a biology book on the human body and come across the word malignant, you might guess that this word means something negative or broken if you already know the word malfunction, which shares the “mal-” prefix.

- Write the word in a sentence, ideally one that is relevant to you. If the word has more than one definition, write a sentence for each.

- Say the word out loud and then say the definition and the sentence you wrote.

- Use the word. Find an occasion to use the word in speech or writing over the next two days.

- Schedule a weekly review with yourself to go over your new words and their meaning.

Attributions

Active Reading Strategies. Authored by: Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. License: CC BY-NC-SA-4.0

Active Learning in EDUC 1300. Authored by: Jolene Carr. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/active-engagement/. License: CC BY 4.0

Chapter 5: Reading to Learn in College Success. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: University of Minnesota. Located at: http://www.oercommons.org/courses/college-success/view. License: CC BY-NC-SA-4.0

Reading Strategies in EDUC 1300. Authored by: Jolene Carr. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/reading-strategies/. License: CC BY 4.0

SQ3R. Provided by: Thousand Insights. Located at: https://thousandinsights.wordpress.com/2009/01/25/sq3r/. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

SQ3R. Provided by: Wikipedia. Located at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SQ3R. License: CC BY-SA 3.0

Understanding SQ3R Presentation. Authored by: Student Success Center OCtech. Located at: https://youtu.be/d0uVLSacIzA. License: CC BY 3.0