7.2 Active Listening

Stevy Scarbrough

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this reading, you will be able to:

- Explain why regular class attendance class is important.

- Define active learning.

- Identify effective participation strategies.

- Identify strategies for obtaining content from a class you missed.

Students don’t always want to go to class. They may have required classes that they find difficult or don’t enjoy, or they may feel overwhelmed by other commitments or feel tired if they have early morning classes. However, even if instructors allow a certain number of unexcused absences, you should aim to attend every class session. Class attendance enhances class performance in the following ways:

- Class participation: If you don’t attend class, you can’t participate in-class activities. Class activities are usually part of your final grade, and they can help you apply concepts you learn from lectures and reading assignments.

- Class interaction: If you rely on learning on your own (by doing the reading assignments outside of class, for example), you’ll miss out on class discussions with fellow students. Your classmates will often have the same questions as you, so going to class enables you to learn from them and ask your instructor about topics you all find difficult.

- Interaction with the instructor: There is a reason why classes are taught by instructors. Instructors specialize in the subjects they teach, and they can provide extra insight and perspective on the material you’re studying. Going to class gives you the chance to take notes and ask questions about the lectures. Also, the more you participate, the more your instructors will come to know you and be aware of any help or support you might need. This will make you feel more comfortable to approach them outside of class if you need advice or are struggling with the course material.

- Increased learning: Even though you will typically spend more time on coursework outside of the classroom, this makes class sessions even more valuable. Typically, in-class time will be devoted to the most challenging or key concepts covered in your textbooks. It’s important to know what these are so you can master them—also they’re likely to show up on exams.

Let’s compare students with different attitudes toward their classes:

Carlos wants to get through college, and he knows he needs the degree to get a decent job, but he’s just not that into it. He’s never thought of himself as a good student, and that hasn’t changed much in college. He has trouble paying attention in those big lecture classes, which mostly seem pretty boring. He’s pretty sure he can pass all his courses as long as he takes the time to study before tests. It doesn’t bother him to skip classes when he’s studying for a test in a different class or finishing a reading assignment he didn’t get around to earlier. He does make it through his first year with a passing grade in every class, even those he didn’t go to very often. Then he fails the midterm exam in his first sophomore class. Depressed, he skips the next couple classes, then feels guilty and goes to the next. It’s even harder to stay awake because now he has no idea what they’re talking about. It’s too late to drop the course, and even a hard night of studying before the final isn’t enough to pass the course. In two other classes, he just barely passes. He has no idea what classes to take next term and is starting to think that maybe he’ll drop out for now.

Karen wants to have a good time in college and still do well enough to get a good job in business afterward. Her sorority keeps a file of class notes for her big lecture classes, and from talking to others and reviewing these notes, she’s discovered she can skip almost half of those big classes and still get a B or C on the tests. She stays focused on her grades, and because she has a good memory, she’s able to maintain OK grades. She doesn’t worry about talking to her instructors outside of class because she can always find out what she needs from another student. In her sophomore year, she has a quick conversation with her academic advisor and chooses her major. Those classes are smaller, and she goes to most of them, but she feels she’s pretty much figured out how it works and can usually still get the grade. In her senior year, she starts working on her résumé and asks other students in her major which instructors write the best letters of recommendation. She’s sure her college degree will land her a good job.

Logan enjoys their classes, even when they have to get up early after working or studying late the night before. They sometimes get so excited by something they learn in class that they rush up to the instructor after class to ask a question. In class discussions, they are not usually the first to speak out, but by the time another student has given an opinion, they have had time to organize their thoughts and enjoys arguing their ideas. Nearing the end of their sophomore year and unsure of what to major in given their many interests, they talk things over with one of their favorite instructors, whom they have gotten to know through office visits. The instructor gives Logan some insights into careers in that field and helps them explore their interests. Logan takes two more courses with this instructor over the next year, and they are comfortable in their senior year going to him to ask for a job reference. When they do, they’re surprised and thrilled when he urges them to apply for a high-level paid internship with a company in the field—that happens to be run by a friend of his.

Think about the differences in the attitudes of these three students and how they approach their classes. One’s attitude toward learning, toward going to class, and toward the whole college experience is a huge factor in how successful a student will be. Make it your goal to attend every class; don’t even think about not going. Going to class is the first step in engaging in your education by interacting with the instructor and other students. Here are some reasons why it’s important to attend every class:

- Miss a class and you’ll miss something, even if you never know it. Even if a friend gives you notes for the class, they cannot contain everything said or shown by the instructor or written on the board for emphasis or questioned or commented on by other students. What you miss might affect your grade or your enthusiasm for the course. Why go to college at all if you’re not going to go to college?

- While some students may say that you don’t have to go to every class to do well on a test, that is very often a myth. Do you want to take that risk?

- Your final grade often reflects how you think about course concepts, and you will think more often and more clearly when engaged in class discussions and hearing the comments of other students. You can’t get this by borrowing class notes from a friend.

- Research shows there is a correlation between absences from class and lower grades. It may be that missing classes causes lower grades or that students with lower grades miss more classes. Either way, missing classes and lower grades can be intertwined in a downward spiral of achievement.

- Your instructor will note your absences, even in a large class. In addition to making a poor impression, you reduce your opportunities for future interactions. You might not ask a question the next class because of the potential embarrassment of the instructor saying that was covered in the last class, which you apparently missed. Nothing is more insulting to an instructor than when you skip a class and then show up to ask, “Did I miss anything important?”

- You might be tempted to skip a class because the instructor is “boring,” but it’s more likely that you found the class boring because you weren’t very attentive or didn’t appreciate how the instructor was teaching.

- You paid a lot of money for your tuition. Get your money’s worth!

Active Listening

Active listening is a particular communication technique that requires the listener to provide feedback on what they hear to the speaker, by way of restating or paraphrasing what they have heard in their own words. The goal of this repetition is to confirm what the listener has heard and to confirm the understanding of both parties. The ability to actively listen demonstrates sincerity, and that nothing is being assumed or taken for granted. Active listening is most often used to improve personal relationships, reduce misunderstandings and conflicts, strengthen cooperation, and foster understanding.

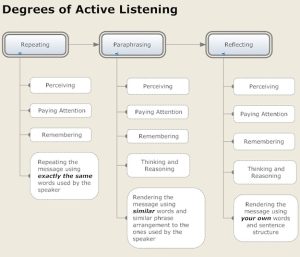

When engaging with a particular speaker, a listener can use several degrees of active listening, each resulting in a different quality of communication with the speaker. This active listening chart shows three main degrees of listening: repeating, paraphrasing, and reflecting.

Active listening can also involve paying attention to the speaker’s behavior and body language. Having the ability to interpret a person’s body language lets the listener develop a more accurate understanding of the speaker’s message.

Principles of Active Listening

- Focus on what is being said. Give the speaker your undivided attention. Clear your mind of anything else.

- Don’t prejudge or assume you already know the material. You want to understand what the person is saying; you don’t need to agree with it.

- Repeat what you just heard. Confirm with the speaker that what you heard is what they said.

- Ask the speaker to expand or clarify. If you are unsure you understand, ask questions; don’t assume.

- Listen for verbal cues and watch for nonverbal cues. Verbal cues are things your instructor says that communicate the importance. Examples are, “This is an important point” or “I want to make sure everyone understands this concept.” Your instructor is telling you what is most important. Nonverbal cues come from facial expressions, body positioning, arm gestures, and tone of voice. Examples include when the instructor repeats herself, gets louder, or starts using more hand gestures.

- Listen for requests. A speaker will often hide a request as a statement of a problem. If a friend says, “I hate math!” this may mean, “Can you help me figure out a solution to this problem?”

Listening in a classroom to learn can be challenging because you are limited by how, and how much, you can interact with an instructor during the class. The following strategies help make listening at lectures more effective and learning more fun.

- Get your mind in the right space. Prepare yourself mentally to receive the information the speaker is presenting by following the previous prep questions and by doing your assignments (instructors build upon work presented earlier).

- Get yourself in the right space. Sit toward the front of the room where you can make eye contact with the instructor easily. Most instructors read the body language of the students in the front rows to gauge how they are doing and if they are losing the class. Instructors also believe students who sit near the front of the room take their subject more seriously and are more willing to give them help when needed or to give them the benefit of the doubt when making a judgment call while assigning grades.

- Eliminate distractions. There are two types of distractions: internal and external distractions.

- Internal distractions are things like being hungry, tired, or distracted by other thoughts. Try to manage these by being well-rested and having a healthy meal before class.

- External distractions are things like a ringing cell phone or people talking in the hallway. To manage these distractions, turn your cell phone off and pack it away in your backpack. If you are using your laptop for notes, close all applications except the one that you use to take notes.

- Look for signals. Each instructor has a different way of telling you what is important. Some will repeat or paraphrase an idea; others will raise (or lower) their voices; others will write related words on the board. Learn what signals your instructors tend to use and be on the lookout for them. When they use that tactic, the idea they are presenting needs to go in your notes and in your mind—and don’t be surprised if it appears on a test or quiz!

- Listen for what is not being said. If an instructor doesn’t cover a subject or covers it only minimally, this signals that that material is not as important as other ideas covered in greater length.

- Sort the information. Decide what is important and what is not, what is clear and what is confusing, and what is new material and what is a review. This mental organizing will help you remember the information, take better notes, and ask better questions.

- Take notes. We cover taking notes in much greater detail later in the next chapter, but for now, think about how taking notes can help recall what your instructor said and how notes can help you organize your thoughts for asking questions.

- Ask questions. Asking questions is one of the most important things you can do in class. Most obviously it allows you to clear up any doubts you may have about the material, but it also helps you take ownership of (and therefore remember) the material. Good questions often help instructors expand upon their ideas and make the material more relevant to students. Thinking through the material critically in order to prepare your questions helps you organize your new knowledge and sort it into mental categories that will help you remember it.

What to Do If…

- Your instructor speaks too fast. Crank up your preparation. The more you know about the subject, the more you’ll be able to pick up from the instructor. Exchange class notes with other students to fill in gaps in notes. Visit the instructor during office hours to clarify areas you may have missed. You might ask the instructor—very politely, of course—to slow down, but habits like speaking fast are hard to break!

- Your instructor has a heavy accent. Sit as close to the instructor as possible. Make connections between what the instructor seems to be saying and what they are presenting on the board or screen. Ask questions when you don’t understand. Visit the instructor during office hours; the more you speak with the instructor the more likely you will learn to understand the accent.

- Your instructor speaks softly or mumbles. Sit as close to the instructor as possible and try to hold eye contact as much as possible. Check with other students if they are having problems listening, too; if so, you may want to bring the issue up with the instructor. It may be that the instructor is not used to the lecture hall your class is held in and can easily make adjustments.

Now That’s a Good Question…

Are you shy about asking questions? Do you think that others in the class will ridicule you for asking a dumb question? Students sometimes feel this way because they have never been taught how to ask questions. Practice these steps, and soon you will be on your way to customizing each course to meet your needs and letting the instructor know you value the course.

- Be prepared. Doing your assignments for a class or lecture will give you a good idea about the areas you are having trouble with and will help you frame some questions ahead of time.

- Position yourself for success. Sit near the front of the class. It will be easier for you to make eye contact with the instructor as you ask the question. Also, you won’t be intimidated by a class full of heads turning to stare at you as you ask your question.

- Don’t wait. Ask your questions as soon as the instructor has finished a thought. Being one of the first students to ask a question also will ensure that your question is given the time it deserves and won’t be cut short by the end of class.

- In a lecture class, write your questions down. Make sure you jot your questions down as they occur to you. Some may be answered in the course of the lecture, but if the instructor asks you to hold your questions until the end of class, you’ll be glad you have a list of the items you need the instructor to clarify or expand on.

- Ask specific questions. “I don’t understand” is a statement, not a question. Give the instructor guidance about what you are having trouble with. “Can you clarify the use of the formula for determining velocity?” is a better way of asking for help. If you ask your question at the end of class, give the instructor some context for your question by referring to the part of the lecture that triggered the question. For example, “Professor, you said the Union troops were emboldened by Lincoln’s leadership. Was this throughout the Civil War, or only after Gettysburg?”

- Don’t ask questions for the sake of asking questions. If your question is not thought out, or if it appears that you are asking the question to try to look smart, instructors will see right through you

Effective Participation Strategies

Like listening, participating in class will help you get more out of class. It may also help you stand out as a student. Instructors notice the students who participate in class (and those who don’t), and participation is often a component of the final grade. “Participation” may include contributing to discussions, class activities, or projects. It means being actively involved. The following are some strategies for effective participation:

- Be a team player: Although most students have classmates they prefer to work with, they should be willing to collaborate in different types of groups. Teamwork demonstrates that a student can adapt to and learn in different situations.

- Share meaningful questions and comments: Some students speak up in class repeatedly if they know that participation is part of their grade. Although there isn’t necessarily anything wrong with this, it’s a good practice to focus on quality vs. quantity. For instance, a quieter student who raises her hand only twice during a discussion but provides thoughtful comments might be more noticeable to an instructor than a student who chimes in with everything that’s said.

- Be prepared: As with listening, effective participation relies on coming to class prepared. Students should complete all reading assignments beforehand and also review any notes from the previous meeting. This way they can come to class ready to discuss and engage. Be sure to write down any questions or comments you have—this is an especially good strategy for quieter students or those who need practice thinking on their feet

Guidelines for Participating in Classes

Smaller classes generally favor discussion, but often instructors in large lecture classes also make some room for participation. A concern or fear about speaking in public is one of the most common fears. If you feel afraid to speak out in class, take comfort from the fact that many others do as well—and that anyone can learn how to speak in class without much difficulty. Class participation is actually an impromptu, informal type of public speaking, and the same principles will get you through both: preparing and communicating.

- Set yourself up for success by coming to class fully prepared.

- Complete reading assignments.

- Review your notes on the reading and previous class to get yourself in the right mindset.

- If there is something you don’t understand well, start formulating your question now.

- Sit in the front with a good view of the instructor, board or screen, and other visual aids. In a lecture hall, this will help you hear better, pay better attention, and make a good impression on the instructor. Don’t sit with friends—socializing isn’t what you’re there for.

- Remember that your body language communicates as much as anything you say. Sit up and look alert, with a pleasant expression on your face, and make good eye contact with the instructor. Show some enthusiasm.

- Pay attention to the instructor’s body language, which can communicate much more than just words. How the instructor moves and gestures, and the looks on their face, will add meaning to the words—and will also cue you when it’s a good time to ask a question or stay silent.

- Take good notes, but don’t write obsessively—and never page through your textbook (or browse on a laptop).

- Don’t eat or play with your cell phone.

- Except when writing brief notes, keep your eyes on the instructor.

- Follow class protocol for making comments and asking questions.

- In a small class, the instructor may encourage students to ask questions at any time, while in some large lecture classes, the instructor may for ask questions at the end of the lecture. In this case, jot your questions in your notes so that you don’t forget them later.

- Don’t say or ask anything just to try to impress your instructor. Most instructors have been teaching long enough to immediately recognize insincere flattery—and the impression this makes is just the opposite of what you want.

- Pay attention to the instructor’s thinking style. Does this instructor emphasize theory more than facts, wide perspectives over specific ideas, abstractions more than concrete experience? Take a cue from your instructor’s approach and try to think in similar terms when participating in class.

- It’s fine to disagree with your instructor when you ask or answer a question. Many instructors invite challenges. Before speaking up, however, be sure you can explain why you disagree and give supporting evidence or reasons. Be respectful.

- Pay attention to your communication style. Use standard English when you ask or answer a question, not slang. Avoid sarcasm and joking around. Be assertive when you participate in class, showing confidence in your ideas while being respectful of the ideas of others. But avoid an aggressive style that attacks the ideas of others or is strongly emotional.

When your instructor asks a question to the class:

- Raise your hand and make eye contact, but don’t call out or wave your hand all around trying to catch their attention.

- Before speaking, take a moment to gather your thoughts and take a deep breath. Don’t just blurt it out—speak calmly and clearly.

When your instructor asks you a question directly:

- Be honest and admit it if you don’t know the answer or are not sure. Don’t try to fake it or make excuses. With a question that involves a reasoned opinion more than a fact, it’s fine to explain why you haven’t decided yet, such as when weighing two opposing ideas or actions; your comment may stimulate further discussion.

- Organize your thoughts to give a sufficient answer. Instructors seldom want a yes or no answer. Give your answer and provide reasons or evidence in support.

When you want to ask the instructor a question:

- Don’t ever feel a question is “stupid.” If you have been paying attention in class and have done the reading and you still don’t understand something, you have every right to ask.

- Ask at the appropriate time. Don’t interrupt the instructor or jump ahead and ask a question about something the instructor may be starting to explain. Wait for a natural pause and a good moment to ask. On the other hand, unless the instructor asks students to hold all questions until the end of class, don’t let too much time go by, or you may forget the question or its relevance to the topic.

- Don’t ask just because you weren’t paying attention. If you drift off during the first half of class and then realize in the second half that you don’t really understand what the instructor is talking about now, don’t ask a question about something that was already covered.

- Don’t ask a question that is really a complaint. You may be thinking, “Why would so-and-so believe that? That’s just crazy!” Take a moment to think about what you might gain from asking the question. It’s better to say, “I’m having some difficulty understanding what so-and-so is saying here. What evidence did they use to argue for that position?”

- Avoid dominating a discussion. It may be appropriate in some cases to make a follow-up comment after the instructor answers your question, but don’t try to turn the class into a one-on-one conversation between you and the instructor.

If You Must Miss a Class…

- Plan in advance: Although nobody can plan to be sick, students should give their instructors advanced notice if they know they will need to miss class for something like a doctor’s appointment. This is not only respectful to the instructor, but they may be able to give you any handouts or assignments that you might otherwise miss. If you anticipate that class will be canceled on account of bad weather, etc., make sure you have all the materials, notes, etc. that you need to work at home. In college, “snow days” are rarely “free days”—i.e., expect that you will be responsible for all the work due on those days when school reopens.

- Talk to fellow students: Ask to borrow class notes from one or two classmates who are reliable note takers. Be sure to also ask them about any announcements or assignments the instructor made during the class you missed.

- Talk to your instructor: Even if you have already emailed or called your instructor, check in with him or her before or after the next class period to collect any missed handouts and ask if anything was assigned. While you can’t expect the instructor to repeat the lecture, you can ask what you should do to stay caught up. But remember the worst thing you can say to an instructor: “I missed class—did you talk about anything important?”

- Do the reading assignment(s) and any other homework. Take notes on any readings to be discussed in the class you missed. If you have questions on the reading or homework, seek help from your classmates. Completing the homework and coming prepared for the next session will demonstrate to your instructor that you are still dedicated to the class.

Attributions

Active Listening in the Classroom. Authored by: Heather Syrett. Provided by: Austin Community College. License: CC BY-NC-SA-4.0

Class Attendance in EDUC 1300. Authored by: Jolene Carr. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/class-attendance. License: CC BY 4.0

Chapter 4: Listening, Taking Notes, and Remembering in College Success. Authored by: Anonymous. Provided by: University of Minnesota. Located at: http://www.oercommons.org/courses/college-success/view. License: CC BY-NC-SA-4.0