2.1 Academic Planning

Stevy Scarbrough

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this reading, you will be able to:

- Describe the different types of degrees you can pursue in college.

- Discuss how to choose your major.

- Describe what career and technical education is.

- Describe the importance of developing an academic plan.

- Identify resources to help you with your academic plan.

This section provides an overview of academic programs and college degrees that are common among many colleges and universities in the United States. Please note that each institution will have its own specific options and requirements, so the intention of this section is both to help you understand your opportunities and to familiarize you with language that colleges typically use to describe these opportunities. After reviewing this section, you should be better able to formulate specific questions to ask at your school or be better prepared to navigate and search your own college’s website.

Types of Degrees

Whereas in most states high school attendance through the 12th grade is mandatory, or compulsory, a college degree may be pursued voluntarily. There are fields that do not require a degree. Bookkeeping, computer repair, massage therapy, and childcare are all fields where certification programs—tracks to study a specific subject or career without need of a complete degree—may be enough.

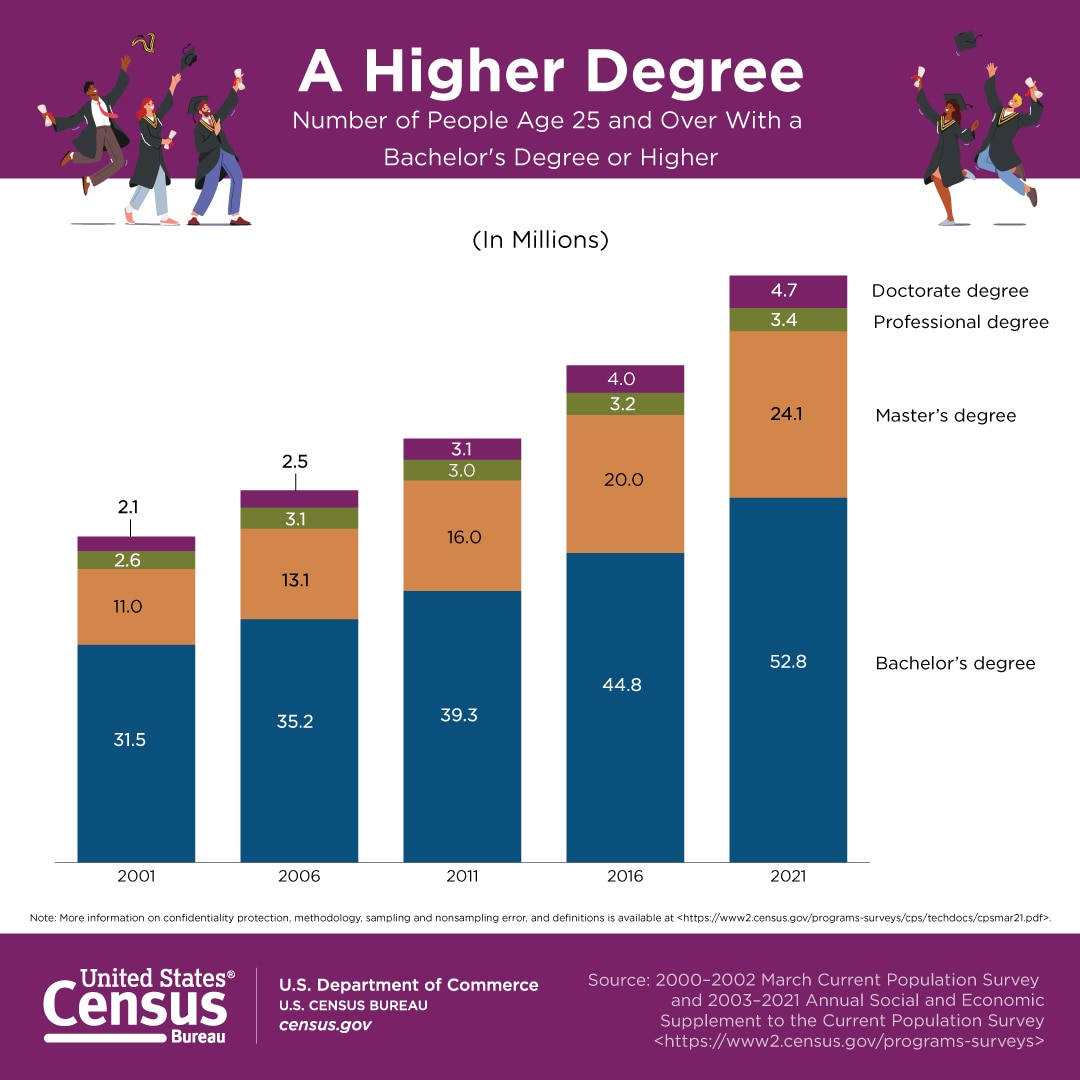

However, many individuals will find that an associate’s or bachelor’s degree is a requirement to enter their desired career field. According to United States Census data published in 2017, more than one-third of the adult population in the country has completed at least a bachelor’s degree, so this may be the degree that is most familiar to you. However, not every job requires a bachelor’s degree, and some require even higher degrees or additional specialized certifications. As you develop your academic plan, it is important to research your field of interest to see what requirements might be necessary or most desirable.

To distinguish between the types of degrees, it is useful to understand that courses are often assigned a number of credits. Credits relate to the calculated hours during a course that a student spends interacting with the instructor and/or the course material through class time, laboratory time, online discussions, homework, etc. Courses at all degree levels are typically assigned a value of one to six credits, although students often need to complete a developmental education course or two, often in English or math. These requirements, which cost as much as typical college courses but do not grant college credit, are meant to provide some basic information students may have missed in high school but that will be necessary to keep up in college-level coursework.

The minimum or maximum number of credits required to graduate with different degrees varies by state or institution, but approximate minimum numbers of credits are explained below. Keep in mind that although a minimum number of credits must be completed to get a certain degree, total credits completed is not the only consideration for graduation—you must take your credits or courses in particular subjects indicated by your college.

To determine your best degree option, it might make sense to do some research to determine what kind of career you’re most interested in pursuing. Visit your campus career center to meet with a counselor to guide you through this process. These services are free to students—similar services can be pricey once you’ve graduated, so take advantage. There are other tools online you can investigate.

Associate’s Degrees

To enter an associate’s degree program, students must have a high school diploma or its equivalent. Associate’s degree programs may be intended to help students enter a technical career field, such as automotive technology, graphic design, or entry-level nursing in some states. Such technical programs may be considered an Associate of Applied Arts (AAA) or Associate of Applied Science (AAS) degrees, though there are other titles as well.

Other associate’s degree programs are intended to prepare a student with the necessary coursework to transfer into a bachelor’s degree program upon graduation. These transfer-focused programs usually require similar general education and foundational courses that a student would need in the first half of a bachelor’s degree program. Transfer-focused associate’s degrees may be called Associate of Arts (AA) or Associate of Science (AS), or other titles, depending on the focus of study.

Bachelor’s Degrees

When someone generally mentions “a college degree,” they are often referring to the bachelor’s degree, or baccalaureate degree. Because it takes four years of full-time attendance to complete a bachelor’s degree, this degree is also referred to as a “four-year degree.” Similar to an associate’s degree, to enter a bachelor’s degree program a student must have completed a high school diploma or its equivalent. Both associate’s degrees and bachelor’s degrees are considered undergraduate degrees, thus students working toward these degrees are often called undergraduates. A student with an associate’s degree may transfer that degree to meet some (usually half) of the requirements of a bachelor’s degree; however, completion of an associate’s degree is not necessary for entry into a bachelor’s degree program.

A bachelor’s degree is usually completed with a minimum of 120 semester credits, or 180 quarter system credits (approximately 40 courses). Some specialized degree programs may require more credits. If an associate’s degree has been transferred, the number of credits from that degree usually counts toward the total credits. For example, if an associate’s degree was 60 credits, then a student must take 60 additional credits to achieve their bachelor’s degree.)

Bachelor of Arts (BA), Bachelor of Science (BS), Bachelor of Science in Nursing (BSN), and Bachelor of Fine Arts (BFA) are the most popular degree titles at this level and differ primarily in their focus on exploring a broader range of subject areas, as with a BA, versus focusing in more depth on a particular subject, as with a BS, BSN, or BFA. Regardless of whether a student is pursuing a BA, BS, BSN, or BFA, each of these programs requires a balance of credits or courses in different subject areas. In the United States, a bachelor’s degree comprises courses from three categories: general education courses, major courses, and electives. A fourth category of courses would be those required for a minor, which we will discuss in more detail in the section on majors and minors.

Core, Required, and Elective Courses

Every college has its own course requirements for different programs and degrees. This information is available in the course catalog (most are now available online). While academic advisors are generally assigned to students to help them plot their path through college and take the most appropriate courses, you should also take this responsibility yourself to ensure you are registering for courses that fit well into your plan for a program completion or degree. In general, there are three types of courses:

- Core courses, sometimes called “general education requirements,” involve a range of courses from which you can choose to meet this general requirement. You may need to take one or more English classes and possibly math or foreign language requirements. You will need a certain number of credits or course hours in certain types of core courses, but you can often choose among various specific courses for how you meet these requirements.

- Required courses in your major are determined by individual academic departments. Whether you choose to major in English, math, engineering, history, a health field, chemistry, business, or any other field, your individual department sets specific required courses you must take and gives you options for a required additional number of credits in the department. You may not need to declare a major for a while, but this is something you can start thinking about now.

- Electives are courses you choose freely to complete the total number of college credits needed for your program or degree. How many electives you may take, how they “count” toward your total, and what kinds of courses are acceptable as electives all vary considerably among different schools and programs.

Most important is that you understand what courses you need and how each counts. Study the college catalog carefully and be sure to talk things over fully with your advisor. Don’t just sign up for courses that sound interesting—you might end up taking courses that don’t count toward your degree at all.

In addition, each term you may have to choose how many courses or hours to take. Colleges have rules about the maximum number of hours allowed for full-time students, but this maximum may in fact be more than you are prepared to manage—especially if you work or have other responsibilities. Taking a light course load, while allowing more time for studying and other activities, could add up over time and result in an extra full year of college (or more!)—at significant additional expense. Part-time students often face decisions based more on time issues. Everyone’s situation is unique, however, and all students should talk this issue over with their advisor each year or term.

Face-to-Face Courses

- a)

b)

Figure 1.4 a) Many core courses at Universities are often large lectures with 100s of students as most students going through the college have to take them. University Lecture – nikolayhg – Pixabay License. b) Upper division courses and community college courses often have smaller class sizes. HCC Government Class – Maryland GovPics – CC BY 2.0.

While most high school classes are fairly small, many college classes are large—up to several hundred students in a large lecture class. Other classes you may take will be as small as high school classes. In large lecture classes you may feel totally anonymous—even invisible—in a very large class. This feeling can get some students in trouble, however. Here are some common mistaken assumptions and attitudes about large classes:

- The instructor won’t notice me sitting there, so I can check e-mail or read for a different class if I get bored.

- The instructor doesn’t know my name or recognize me, so I don’t even need to go to class as long as I can borrow someone’s notes to find out what happens.

- I hate listening to lectures, so I might as well think about something else because I’m not going to learn anything this way anyway.

These comments all share the same flawed attitude about college: it’s up to the instructor to teach in an entertaining way if I am to learn at all—and it’s actually the college’s or instructor’s fault that I’m stuck in this large class, so they’re to blame if I think about or do other things. But remember, in college, you take responsibility for your own learning. Sure, a student is free to try to sleep in a lecture class, or not attend the class at all—the same way a student is “free” to fail any class he or she chooses!

If you dislike large lecture classes but can’t avoid them, the best solution is to learn how to learn in such a situation. Later chapters will give you tips for improving this experience. Just remember that it’s up to you to stay actively engaged in your own learning while in college—it’s not the instructor’s job to entertain you enough to “make” you learn.

There is one thing you need to know right away. Even in a lecture hall holding three hundred students, your instructors do know who you are. They may not know your name right away or even by the end of the term, but they see you sitting there, doing whatever you are doing, looking wherever you are looking—and will form a distinct impression of you. Instructors do have academic integrity and won’t lower your grade on an exam because you slept once in class, but the impression you make just might affect how far instructors go out of their way to offer a helping hand. Interacting with instructors is a crucial part of education—and the primary way students learn. Successful interaction begins with good communication and mutual respect. If you want your instructors to respect you, then you need to show respect for them and their classes as well.

Online Courses

Figure 1.5 Learning Management Systems (LMS) like this one are used to house online classrooms. Psychology in Cinema – Deepak Kumar – CC BY-NC-SA 2.0.

Most colleges now offer online courses or hybrid courses that meet in-person part of the time and a substantial online component. You experience an online course via a computer rather than a classroom. Many different variations exist, but all online courses share certain characteristics, such as working independently and communicating with the instructor (and sometimes other students) primarily through written computer messages. If you have never taken an online course, carefully consider what’s involved to ensure you will succeed in the course.

- You need to own or have frequent access to a recent model of computer with a high-speed Internet connection.

- Without the set hours of a class, you need to be self-motivating to schedule your time to participate regularly.

- Without an instructor or other students in the room, you need to be able to pay attention effectively to the computer screen. Learning on a computer is not as simple as passively watching television! Take notes.

- Without reminders in class and peer pressure from other students, you’ll need to take responsibility to complete all assignments and papers on time.

- Since your instructor will evaluate you primarily through your writing, you need good writing skills for an online course. If you believe you need to improve your writing skills, put off taking an online course until you feel better prepared.

- You must take the initiative to ask questions if you don’t understand something.

- You may need to be creative to find other ways to interact with other students in the course. You could form a study group and get together regularly in person with other students in the same course.

If you feel you are ready to take on these responsibilities and are attracted to the flexibility of an online course and the freedom to schedule your time in it, see what your college has available.

Choosing Your Major

Choosing a college major can have a big impact on your career choices, especially if you are following a technical or vocational program of study. After all, it’s hard to become a pharmacist if you study computer networking. But students often get too anxious about choosing a major or program of studies. Certainly many two-year students have a very clear idea of what they are studying and the job they expect to land after completing their degree, and you probably feel confident enough in your choice of program of study to make the investment for tuition in that program. But there is no need to panic over your choice of major or program of studies:

- Your choice of major or program will be important only for your first job after college; most people change careers (not just jobs, but careers) five times or more in their lifetime, so there is no possible major that will cover that level of flexibility.

- Many majors and programs share foundation courses with other majors, so you can usually change your major without having wasted your time in courses that will be unrelated to your new major. Chances are that if you change your major, it will be to something similar, especially if you have completed an occupational interest survey as recommended earlier in this chapter.

- Most students change their major at least once, and many will change majors two or three times before they graduate.

- If a change in major does cause a delay in completing your degree, it may be a good investment of time to follow a career path you are truly happy with.

Career and Technical Education

When choosing to attend college and your major, it is important to make that decision based on how it will help you work toward your desired career. Not all careers require a Bachelor’s degree. Your desired career may be housed within the Career and Technical Education track. Career and Technical Education (CTE) is typically offered at community colleges and trade schools. CTE provides students with valuable education in high-demand jobs. There are 16 career cluster areas of CTE (ACTE, n.d.; Herrity, 2023):

- Agriculture, food, and natural resources

- Arts, Audio/Visual Technology, and Communications

- Business management and administration

- Construction and architecture

- Education and Training

- Finance

- Government and public administration

- Health Science

- Hospitality and tourism

- Human Services

- Information Technology

- Law, public safety, and security

- Logistics, distribution, and transportation

- Manufacturing

- Sales, marketing, and service

- Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM)

Planning Your Path

As previously noted, most associate’s degrees require a minimum of 60 semester credit hours or 90 quarter credit hours for completion, and bachelor’s degrees minimally require a total of 120 or 180 credits respectively. Some individuals refer to these degrees as “two-year” and “four-year” degrees. To complete an associate’s degree in two years, you would need to take about five classes each semester or four classes each quarter during both years of your attendance. To complete a bachelor’s degree in four years, you would need to take five classes each semester or four classes each quarter during each of your four years. It is therefore entirely possible to complete these degrees in two and four years, particularly if you use the three primary resources that colleges provide to help you with your planning: curriculum maps, academic advisors, and interactive planning technology.

Curriculum Maps

Many colleges and universities will provide curriculum maps, or course checklists to illustrate the sequence of courses necessary to follow this timeline. These timelines often assume that you are ready to take college-level math and English courses and that you will be attending college as a full-time student. If placement tests demonstrate a need for prerequisite math and English coursework to get you up to speed, your timeline will likely be longer.

Many students attend college part-time, often because of family or work responsibilities. This will obviously have an impact on your completion timeline as well. Programs that have special requirements may also require that you plan for additional time. For example, it may be the case that you cannot take other courses while completing clinicals or student teaching, so you will need to plan accordingly. Alternatively, you may be able to speed up, or accelerate, your timeline to degree by taking courses during summer or winter terms. Or if you take fewer than 15 credits per semester, you can take courses during the summer terms to “make up” those credits and stay on track toward those two- or four-year graduation goals.

Academic Advisors

All colleges and universities provide resources such as a curriculum map to assist you with your academic planning. Academic advisors may also be called success coaches, mentors, preceptors, or counselors. They may be staff members, or faculty may provide advisement as an additional role to their teaching responsibilities. Regardless of what your college calls this role, academic advisors are individuals who are able to assist you in navigating the puzzle of your academic plan and piecing your courses and requirements together with your other life obligations to help you meet your goals.

An advisor is an expert on college and major requirements and policies, while you are the expert on your life circumstances and your ability to manage your study time and workload. It is also an advisor’s responsibility to understand the details of your degree requirements. This person can teach you how to best utilize college resources to make decisions about your academic and career path. An advisor can help you connect with other college staff and faculty who might be integral to supporting your success. Together with your advisor, you can create a semester-by-semester plan for the courses you will take and the special requirements you will meet. Refer to the end of this section for a detailed planning template that you could use in this process. Even if your college does not require advising, it is wise to meet with your advisor every semester to both check your progress and learn about new opportunities that might lend you competitive advantage in entering your career.

Academic advisors can help you:

- Set educational and career goals

- Select a major and/or minor

- Understand the requirements of your degree

- Navigate the online tools that track the progress of your degree

- Calculate your GPA and understand how certain choices may impact your GPA

- Discuss your academic progress from semester to semester

- Assist with time management strategies

- Connect with other support and resources at the college such as counseling, tutoring, and career services

- Navigate institutional policies such as grade appeals, admission to special programs, and other concerns

- Strategize how to make important contacts with faculty or other college administrators and staff as necessary (such as discussing how to construct professional emails)

- Discuss transfer options, if applicable

- Prepare for graduate school applications

Interactive Planning Technology

In addition to a curriculum map and an advisor, colleges and universities usually have technological tools that can assist you in your academic planning. Degree audit reporting systems, for example, are programmed to align with degree requirements and can track individual student progress toward completion. They function like an interactive checklist of courses and special requirements. Student planning systems often allow students to plan multiple semesters online, to register for planned courses, and to track the progress of their plan. Though friends and family are well-intentioned in providing students with planning advice and can provide important points for students to consider, sometimes new students make the mistake of following advice without consulting their college’s planning resources. It’s important to bring all of these resources together as you craft your individual plan.

Despite all of the resources and planning assistance that is available to you, creating an individual plan can still be a daunting task. Making decisions about which major to pursue, when to take certain courses, and whether to work while attending school may all have an impact on your success, and it is tough to anticipate what to expect when you’re new to college. Taking the time to create a plan and to revise it when necessary is essential to making well-informed, mindful decisions. Spur-of-the-moment decisions that are not well-informed can have lasting consequences to your progress.

The key to making a mindful decision is to first be as informed as possible about your options. Make certain that you have read the relevant resources and discussed the possibilities with experts at your college. Then you’ll want to weigh your options against your values and goals. You might ask: Which option best fits my values and priorities? What path will help me meet my goals in the timeframe I desire? What will be the impact of my decision on myself or on others? Being well-informed, having a clear sense of purpose, and taking the necessary time to make a thoughtful decision will help to remove the anxiety associated with making the “right” decision, and help you make the best decision for you.

Changes to Your Plan

Though we’ve discussed planning in a great degree of detail, the good news is that you don’t have to have it all figured out in order to be successful. Recall the upside-down puzzle analogy from earlier in this chapter. You can still put a puzzle together picture-side down by fitting together the pieces with trial and error. Similarly, you can absolutely be successful in your academic and career life even if you don’t have it all figured out. It will be especially important to keep this in mind as circumstances change or things don’t go according to your original plan.

Expecting Change

After you’ve devoted time to planning, it can be frustrating when circumstances unexpectedly change. Change can be the result of internal or external factors. Internal factors are those that you have control over. They may include indecision, or changing your mind about a situation after receiving new information or recognizing that something is not a good fit for your values and goals. Though change resulting from internal factors can be stressful, it is often easier to accept and to navigate because you know why the change must occur. You can plan for a change and make even better decisions for your path when the reason for change is, simply put—you! Ray’s story demonstrates how internal factors contribute to his need or desire to change plans.

External factors that necessitate change are often harder to plan for and accept. Some external factors are very personal. These may include financial concerns, your health or the health of a loved one, or other family circumstances, such as in Elena’s example. Other external factors may be more related to the requirements of a major or college. For example, perhaps you are not accepted into the college or degree program that you had always hoped to attend or study. Or you may not perform well enough in a class to continue your studies without repeating that course during a semester when you had originally planned to move on to other courses. Change caused by external factors can be frustrating. Because external factors are often unexpected, when you encounter them you’ll often have to spend more time changing your plans or even revising your goals before you’ll feel as though you’re back on track.

Managing Change

It is important to recognize that change, whether internal or external, is inevitable. You can probably think of an example of a time when you had to change your plans due to unforeseen circumstances. Perhaps it’s a situation as simple as canceling a date with friends because of an obligation to babysit a sibling. Even though this simple example would not have had long-term consequences, you can probably recall a feeling of disappointment. It’s okay to feel disappointed; however, you’ll also want to recognize that you can manage your response to changing circumstances. You can ask yourself the following questions:

- What can I control in this situation?

- Do I need to reconsider my values?

- Do I need to reconsider my goals?

- Do I need to change my plans as a result of this new information or these new circumstances?

- What resources, tools, or people are available to assist me in revising my plans?

When encountering change, it helps to remember that decision-making and planning are continuous processes. In other words, active individuals are always engaged in decision-making, setting new plans, and revising old plans. This continuous process is not always the result of major life-changing circumstances either. Oftentimes, we need to make changes simply because we’ve learned some new information that causes a shift in our plans. Planning, like learning, is an ongoing lifetime process.

Asking for Help

Throughout this reading we have made mention of individuals who can help you plan your path, but noted that your path is ultimately your own. Some students make the mistake of taking too much advice when planning and making decisions. They may forgo their values and goals for others’ values and goals for them. Or they may mistakenly trust advice that comes from well-meaning but ill-informed sources.

In other cases, students grapple with unfamiliar college paperwork and technology with little assistance as they proudly tackle perhaps newfound roles as adult decision makers. It’s important to know that seeking help is a strength, not a weakness, particularly when that help comes from well-informed individuals who have your best interests in mind. When you share your goals and include others in your planning, you develop both a support network and a system of personal accountability. Being held accountable for your goals means that others are also tracking your progress and are interested in seeing you succeed. When you are working toward a goal and sticking to a plan, it’s important to have unconditional cheerleaders in your life as well as folks who keep pushing you to stay on track, especially if they see you stray. It’s important to know who in your life can play these roles.

Mentors

When making academic decisions and career plans, it is also useful to have a mentor who has had similar goals. A mentor is an experienced individual who helps to guide a mentee, the less experienced person seeking advice. A good mentor for a student who is engaged in academic and career planning is someone who is knowledgeable about the student’s desired career field and is perhaps more advanced in their career than an entry-level position. This is a person who can model the type of values and behaviors that are essential to a successful career. Your college or university may be able to connect you with a mentor through an organized mentorship program or through the alumni association. If your college does not have an organized mentor program, you may be able to find your own by reaching out to family friends who work in your field of interest, searching online for a local professional association or organization related to your field (as some associations have mentorship programs as well), or speaking to the professors who teach the courses in your major.

Attributions

College Success Author: Amy Baldwin Provided by: OpenStax Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/college-successLinks to an external site. License: CC BY 4.0Links to an external site.

College Success. Author: Amber Gilewski. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-collegesuccess-2/chapter/text-causes-of-stress/ License: CC BY: Attribution

References

Press FAQs on Career and Technical Education (n.d.). Association for Career & Technical Education. Retrieved from https://www.acteonline.org/press-faqs-on-career-and-technical-education/

Herrity, J. (2023, June 30). Career and technical education: Definition and careers. Indeed. Retrieved from https://www.indeed.com/career-advice/career-development/career-and-technical-education

Brookdale Community College Office of Career and Leadership Development. (2016). Your Career Checklist. Retrieved from: http://www.brookdalecc.edu/career

American College Health Association, 2018 https://www.acha.org/documents/ncha/NCHA-II_Spring_2018_Reference_Group_Executive_Summary.pdf

NIDA’s DrugFacts: Electronic Cigarettes (e-Cigarettes)

“One Year On: Unhealthy Weight Gains, Increased Drinking Reported by Americans Coping with Pandemic Stress.” American Psychological Association, 11 Mar. 2021, www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2021/03/one-year-pandemic-stress

“Stress Management.” Mayo Clinic, 2016, http://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/stress-management/in-depth/stress/art-20046037

Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mental_health

NAMI, https://www.nami.org/NAMI/media/NAMI-Media/Images/FactSheets/Anxiety-Disorders-FS.pd

NIMH, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-faq/index.shtm

https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/how-we-can-all-prevent-suicide/

https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/suicide-faq/index.shtml