8.2 Studying and Test Taking

Stevy Scarbrough

Learning Objectives

Upon completion of this reading, you will be able to:

- Describe the pomodoro technique.

- Identify three myths about studying.

- Describe three strategies for memorizing and learning material.

- Describe three strategies for studying.

- Define test anxiety

- Identify sources of test anxiety and techniques for preventing and controlling it.

Kerri didn’t need to study in high school. She made good grades, and her friends considered her lucky because she never seemed to sweat exams or cram. In reality, Kerri did her studying during school hours, took excellent notes in class, asked great questions, and read the material before class meetings—all of these are excellent strategies. Kerri just seemed to do them without much fuss.

Then when she got to college, those same skills weren’t always working as well. Sound familiar? She discovered that, for many classes, she needed to read paragraphs and textbook passages more than once for comprehension. Her notes from class sessions were longer and more involved—the subject material was more complicated and the problems more complex than she had ever encountered. College isn’t high school, as most students realize shortly after enrolling in a higher ed program. Some old study habits and test-taking strategies may serve as a good foundation, but others may need major modification.

It makes sense that, the better you are at studying and test taking, the better results you’ll see in the form of high grades and long-term learning and knowledge acquisition. And the more experience you have using your study and memorization skills and employing success strategies during exams, the better you’ll get at it. But you have to keep it up—maintaining these skills and learning better strategies as the content you study becomes increasingly complex is crucial to your success. Once you transition into a work environment, you will be able to use these same skills that helped you be successful in college as you face the problem-solving demands and expectations of your job. Earning high grades is one goal, and certainly a good one when you’re in college, but true learning means committing content to long-term memory.

Preparing to Study

Studying takes dedication, but you can still learn some techniques to help you be a more effective learner. Two major and interrelated techniques involve avoiding distractions to the best of your ability and creating a study environment that works to help you concentrate.

Avoiding Distractions

We have always had distractions—video games, television shows, movies, music, friends—even housecleaning can distract us from doing something else we need to do, like study for an exam. That may seem extreme, but sometimes vacuuming is the preferred activity to buckling down and working through calculus problems! Cell phones, tablets, and portable computers that literally bring a world of possibilities to us anywhere have brought distraction to an entirely new level. When was the last time you were with a large group of people when you didn’t see at least a few people on devices?

When you study, your biggest challenge may be to block out all the competing noise. And letting go of that connection to our friends and the larger world, even for a short amount of time, can be difficult. Perhaps the least stressful way to allow yourself a distraction-free environment is to make the study session a definite amount of time: long enough to get a significant amount of studying accomplished but short enough to hold your attention.

You can increase that attention time with practice and focus. Pretend it is a professional appointment or meeting during which you cannot check e-mail or texts or otherwise engage with your portable devices. We have all become very attached to the ability to check in—anonymously on social media or with family and friends via text, chat, and calls. If you set a specific amount of time to study without interruptions, you can convince your wandering mind that you will soon be able to return to your link to the outside world. The Pomodoro Technique is a good way to break up your study session so that you maintain your focus.

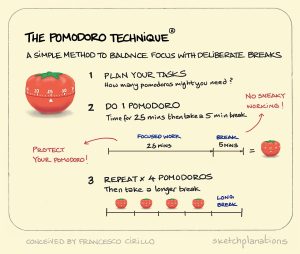

The Pomodoro Technique was developed by Francesco Cirillo. The basic concept is to use a timer to set work intervals that are followed by a short break. The intervals are usually about 25 minutes long and are called pomodoros, which comes from the Italian word for tomato because Cirillo used a tomato-shaped kitchen timer to keep track of the intervals.

A modified version for studying:

- Decide on the task to be done. (What class/topic? Are you reading, taking notes, reviewing?)

- Set your time for 25 minutes.

- Work on the task.

- When the timer goes off, take a 5 minute break. You have just finished one pomodoro.

- Go back and repeat Steps 1-4. To keep your mind from wandering or getting bored, you can switch to a different class/topic, or stick with the class/topic you started with. After four pomodoros take a longer break of 15–30 minutes. You can continue doing as many pomodoros in a row as you like to fit into your study session.

There are several reasons this technique is deemed effective for many people. One is the benefit that is derived from quick cycles of work and short breaks. This helps reduce mental fatigue and the lack of productivity caused by it. Another is that it tends to encourage practitioners to break tasks down to things that can be completed in about 25 minutes, which is something that is usually manageable from the perspective of time available. It is much easier to squeeze in three 25-minute sessions of work time during the day than it is to set aside a 75- minute block of time.

When you prepare for your optimal study session, remember to do these things:

- Put your phone out of sight—in another room or at least some place where you will not see or hear it vibrate or ring. Just flipping it over is not enough.

- Turn off the television or music (more on that in the next section).

- Unless you are deliberately working with a study group, study somewhere alone if possible or at least away from others enough to not hear them talking.

If you live with lots of other people or don’t have access to much privacy, see if you can negotiate some space alone to study. Ask others to leave one part of the house or an area in one room as a quiet zone during certain hours. Ask politely for a specific block of time; most people will respect your educational goals and be willing to accommodate you. If you’re trying to work out quiet zones with small children in the house, the bathtub with a pillow can make a fine study oasis.

Debunking Study Myths

MYTH #1: You can multitask while studying.

How many times do you eat in the car? Watch TV while you write out a grocery list? Listen to music while you cook dinner? What about type an e-mail while you’re on the phone with someone else and jot down notes about the call? The common term for this attempt to do more than one thing at a time is multitasking, and almost everyone does it at some point. On some days, you simply cannot accomplish all that you want to get done, so you double up. The problem is, multitasking doesn’t really work.

Research on multitasking has found that students who try to read texts while engaging in some form of instant messaging take a significantly longer amount of time to read the same text as students who focus solely on reading with no distractions, but performed similarly to their peers on reading comprehension (Fox, Rosen, & Crawford, 2009). However, adding time constraints, such as would be found in real-world conditions, like having to go to work, students who were multitasking while trying to study suffered significant impairments in their performance (Lee, Lin & Robertson, 2012; Srivastava, 2013). These effects to performance are also present when students attempt to multitask during class such as texting ( Ellis, Daniels & Jauregui, 2010, Rosen, Lim, Carrier & Cheever, 2011, Dietz & Henrich, 2014) and using laptops, which can also create distractions for students nearby (Sana, Weston, & Cepeda, 2013).

MYTH #2: Highlighting main points of a text is useful.

Another myth of studying that seems to have a firm hold is that the idea of highlighting text—in and of itself—is the best way to review study material. It is one way, and you can get some benefit from it, but don’t trick yourself into spending too much time on this surface activity and consider your study session complete. Annotating texts or notes is a first-step type of study practice. If you allow it to take up all your time, you may want to think you are fully prepared for an exam because you put in the time. Actually, you need much more time reviewing and retrieving your lessons and ideas from the text or class lecture as well as quizzing yourself to accomplish your goal of learning so you can perform well on the exam. Highlighting is a task you can do rather easily, and it makes you feel good because you are actively engaging with your text, but true learning needs more steps.

MYTH #3: Studying effectively is effortless.

There is nothing effortless about studying. This is why so many students don’t put in the time necessary to learn complex material: it takes time, effort, and, in some cases, a little drudgery. This is not to say that the outcome, learning—and maybe making an A—is not pleasant and rewarding. It is just that when done right, learning takes focus, deliberate strategies, and time. Think about a superstar athlete who puts in countless hours of drills and conditioning so that they make their work on the field look easy. If you can also enjoy the studying, the skill development, and the knowledge building, then you will most likely be more motivated to do the work.

Memorization Strategies

Everyone wishes they had a better memory or a stronger way to use memorization. You can make the most of the memory you have by making some conscious decisions about how you study and prepare for exams. Practicing effective memorization is when you use a trick, technique, or strategy to recall something—for another class, an exam, or even to bring up an acquaintance’s name in a social situation. Really whatever works for you to recall information is a good tool to have. You can create your own quizzes and tests to go over material from class. You can use mnemonics to jog your memory. You can work in groups to develop unique ways to remember complex information. Whatever methods you choose to enhance your memory, keep in mind that repetition is one of the most effective tools in any memory strategy. Do whatever you do over and over for the best results.

Using Mnemonics

Mnemonics (pronounced new-monics) are a way to remember things using reminders. Did you learn the points of the compass by remembering NEWS (north, east, west, and south)? Or the notes on the music staff as FACE or EGBDF (every good boy does fine)? These are mnemonics. When you’re first learning something and you aren’t familiar with the foundational concepts, these help you bring up the information quickly, especially for multistep processes or lists. After you’ve worked in that discipline for a while, you likely don’t need the mnemonics, but you probably won’t forget them either. You can certainly make up your own mnemonics, but be careful that your reminder isn’t so complex and convoluted that it is more difficult to remember than the information you were relating it to.

Practicing Concept Association

When you study, you’re going to make connections to other things—that’s a good thing. It shows a highly intelligent ability to make sense of the world when you can associate like and even somewhat unlike components. If, for instance, you were reading Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” and you read the line that he had been in Birmingham, you may remember a trip you took with your family last summer through Alabama and that you passed by and visited the civil rights museum in Birmingham. This may remind you of the different displays you saw and the discussions you had with your family about what had happened concerning civil rights in the 1950s,’60s, and ’70s in the United States.

This is a good connection to make, but if your assignment is to critique the literary aspects of King’s long epistle, you need to be able to come back to the actual words of the letter and see what trends you can see in his writing and why he may have used his actual words to convey the powerful message. The connection is fine, but you can’t get lost in going down rabbit holes that may or may not be what you’re supposed to be doing at the time. Make a folder for this assignment where you can put things such as a short summary of your trip to Alabama. You may eventually include notes from this summary in your analysis. You may include something from a website that shows you information about that time period. Additionally, you could include items about Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and death and his work for civil rights. All of these elements may help you understand the significance of this one letter, but you need to be cognizant of what you’re doing at the time and remember it is not usually a good idea to just try to keep it all in your head. The best idea is to have a way to access this information easily, either electronically or in hard copy, so that if you are able to use it, you can find it easily and quickly.

Generating Idea Clusters

Like mnemonics, idea clusters are nothing more than ways to help your brain come up with ways to recall specific information by connecting it to other knowledge you already have. For example, Andrea is an avid knitter and remembers how to create complicated stitches by associating them with nursery rhymes she read as a child. A delicate stitch that requires concentration because it makes the yarn look like part of it is hiding brings to mind Red Riding Hood, and connecting it to that character helps Andrea recall the exact order of steps necessary to execute the design. You can do the same thing with song lyrics, lines from movies, or favorite stories where you draw a connection to the well-known phrase or song and the task you need to complete.

Three Effective Study Strategies

There are more than three study strategies, but focusing on the most effective strategies will make an enormous difference in how well you will be able to demonstrate learning (also known as “acing your tests”). Here is a brief overview of each of the three strategies:

- Spacing—This has to do with when you study. Hint: Don’t cram; study over a period of days, preferably with “breaks” in between.

- Interleaving—This has to do with what you study. Hint: Don’t study just one type of content, topic, chapter, or unit at a time; instead, mix up the content when you study.

- Practice testing—This has to do with how you study. Hint: Don’t just reread content. You must quiz or test your ability to retrieve the information from your brain.

Spacing

We all know that cramming is not an effective study strategy, but do we know why? Research on memory suggests that giving yourself time in between study sessions actually helps you forget the information. And forgetting, which sounds like it would be something you don’t want to do, is actually good for your ability to remember information long-term. That’s because every time you forget something, you need to relearn it, leading to gains in your overall understanding and “storage” of the material. The table below demonstrates how spacing works. Assume you are going to spend about four and a half hours studying for a Sociology exam. Cramming would have you spending most of those hours the night before the exam. With spacing, on the other hand, you would space out your studying on different days throughout the week.

| Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | Monday | |

| Cramming | Study for 4.5 hours | Sociology Exam | |||||

| Spacing | Study for 90 minutes | Study for 90 minutes | Study for 90 minutes | Sociology Exam |

Interleaving

One particular studying technique is called interleaving, which calls for students to mix up the content that is being studied. This means not just spending the entire study session on one sort of problem and then moving on to a different sort of problem at a later time.

If you take the schedule we used for the spacing example above, we can add the interleaving concepts to it. Notice that interleaving includes revisiting material from a previous chapter or unit or revisiting different types of problems or question sets. The benefit is that your brain is “mixing up” the information, which can sometimes lead to short-term forgetting but can lead to long-term memory and learning.

| Tuesday | Wednesday | Thursday | Friday | Saturday | Sunday | Monday |

|

Reread Sociology, Chapter 1. Reorganize notes |

Reread Sociology, Chapter 1 and 2 Take Ch 1 online quiz. Create Chapter 2 concept map |

Reread Sociology, Chapters 1-3. Take online quizzes for chapters 2 and 3. Reorganize notes. Create practice test |

Reread notes. Review items missed on online quizzes. Take practice test and review challenge areas. |

EXAM in sociology, Chapters 1-3 |

Practice Testing

You can do a practice “test” in two ways. One is to test yourself as you are reading or taking in information. This is a great way to add a little variety to your studying. You can ask yourself what a paragraph or text section means as you read. To do this, read a passage in a text, cover up the material, and ask yourself, “What was the main idea of this section?” Recite aloud or write down your answer, and then check it against the original information.

Another, more involved, way to practice test is to create flashcards or an actual test by writing a test. This takes more time, but there are online programs such as Quizlet that make it a little easier. Practice testing is an effective study strategy because it helps you practice retrieving information, which is what you want to be able to do when you are taking the real test.

One of the best ways to learn something is to teach it to someone else, so ask a friend or family member if you can explain something to them, and teach them the lesson. You may find you know more about the subject than you thought . . . or you may realize quickly that you need to do more studying. Why does teaching someone else rank as one of the most effective ways to learn something? It is a form of practice testing that requires you to demonstrate you know something in front of someone else! No one wants to look like they don’t know what they are talking about, even if it your audience is another classmate.

Test Taking

Once you are practicing good study habits, you’ll be better prepared for actual test taking. Since studying and test taking are both part of learning, honing your skills in one will help you in the other.

Probably the most obvious differences between your preparation for an exam and the actual test itself is your level of urgency and the time constraints. A slight elevation in your stress level can actually be OK for testing—it keeps you focused and on your game when you need to bring up all the information, thinking, and studying to show what you’ve learned. Properly executed, test preparation mixed in with a bit of stress can significantly improve your actual test-taking experience.

Establishing Realistic Expectations for Test Situations

Would you expect to make a perfect pastry if you’ve never learned how to bake? Or paint a masterpiece if you’ve never tried to work with paints and brushes? Probably not. But often we expect ourselves to perform at much higher levels of achievement than that for which we’ve actually prepared. If you become very upset and stressed if you make any score lower than the highest, you probably need to reevaluate your own expectations for test situations. Striving to always do your best is an admirable goal. Realistically knowing that your current best may not achieve the highest academic ratings can help you plot your progress.

Realistic continuous improvement is a better plan, because people who repeatedly attempt challenges for which they have not adequately prepared and understandably fail (or at least do not achieve the desired highest ranking) often start moving toward the goal in frustration. They simply quit. This doesn’t mean you settle for mediocre grades or refrain from your challenges. It means you become increasingly aware of yourself and your current state and potential future. Know yourself, know your strengths and weaknesses, and be honest with yourself about your expectations.

Prioritizing Time Surrounding Test Situations

Keep in mind that you don’t have any more or less time than anyone else, so you can’t make time for an activity. You can only use the time everyone gets wisely and realistically. Exams in college classes are important, but they are not the only significant events you have in your classes. In fact, everything leading up to the exam, the exam itself, and the post-exam activities are all one large continuum. Think of the exam as an event with multiple phases, more like a long-distance run instead of a 50-yard dash. Step back and look at the big picture of this timeline. Draw it out on paper. What needs to happen between now and the exam so you feel comfortable, confident, and ready? If your instructor conducts some sort of pre-exam summary or prep session, make sure to attend. These can be invaluable. If this instructor does not provide that sort of formal exam prep, create your own with a group of classmates or on your own.

Test Anxiety

For many test-takers, preparing for a test and taking a test can easily cause worry and anxiety. In fact, most students report that they are more stressed by tests and schoolwork than by anything else in their lives, according to the American Test Anxiety Association. Most of us have experienced this. It is normal to feel stress before an exam, and in fact, that may be a good thing. Stress motivates you to study and review, generates adrenaline to help sharpen your reflexes and focus while taking the exam, and may even help you remember some of the material you need. But suffering too many stress symptoms or suffering any of them severely will impede your ability to show what you have learned. Test anxiety is a psychological condition in which a person feels distressed before, during, or after a test or exam to the point where stress causes poor performance. Anxiety during a test interferes with your ability to recall knowledge from memory as well as your ability to use higher-level thinking skills effectively.

- Roughly 16–20% of students have high test anxiety.

- Another 18% have moderately high test anxiety.

- Test anxiety is the most common academic impairment in grade school, high school, and college.

Below are some effects of moderate anxiety:

- Being distracted during a test

- Having difficulty comprehending relatively simple instructions

- Having trouble organizing or recalling relevant information

- Crying

- Illness

- Eating disturbance

- High blood pressure

- Acting out

- Toileting accidents

- Sleep disturbance

- Cheating

- Negative attitudes towards self, school, subjects

Below are some effects of extreme test anxiety:

- Overanxious disorder

- Social phobia

- Suicide

Poor test performance is also a significant outcome of test anxiety. Test-anxious students tend to have lower study skills and lower test-taking skills, but research also suggests that high levels of emotional distress correlate with reduced academic performance overall. Highly test-anxious students score about 12 percentile points below their low-anxiety peers. Students with test anxiety also have higher overall dropout rates. And test anxiety can negatively affect a student’s social, emotional, and behavioral development, as well as feelings about themselves and school.

Why does test anxiety occur? Inferior performance arises not because of intellectual problems or poor academic preparation. It occurs because testing situations create a sense of threat for those who experience test anxiety. The sense of threat then disrupts the learner’s attention and memory. Other factors can influence test anxiety, too. Students with disabilities and students in gifted education classes tend to experience high rates of test anxiety. If you experience test anxiety, have hope! Experiencing test anxiety doesn’t mean that there’s something wrong with you or that you aren’t capable of performing well in college. The trick is to keep stress and anxiety at a level where it can help you do your best rather than get in your way.

Strategies for Preventing and Controlling Test Anxiety

There are steps you should take if you find that stress is getting in your way:

- Be prepared. A primary cause of test anxiety is not knowing the material. If you take good class and reading notes and review them regularly, this stressor should be greatly reduced if not eliminated. You should be confident going into your exam (but not overconfident).

- Practice! One of the best ways to prepare for an exam is to take practice tests. To overcome test-taking anxiety, practice test-taking in a test-like environment, like a study room in the library. Practice staying calm, relaxed, and confident. If you find yourself feeling overly anxious, stop and start again.

- Avoid negative thoughts. Your own negative thoughts—“I’ll never pass this exam” or “I can’t figure this out, I must be really stupid!”—may move you into a spiraling stress cycle that in itself causes enough anxiety to block your best efforts. When you feel you are brewing a storm of negative thoughts, stop what you are doing and clear your mind. Don’t practice having anxiety! Allow yourself to daydream a little; visualize yourself in pleasant surroundings with good friends. Don’t go back to work until you feel the tension release. Sometimes it helps to take a deep breath and shout “STOP!” and then proceed with clearing your mind. Once your mind is clear, repeat a reasonable affirmation to yourself—“I know this stuff”—before continuing your work.

- Visualize success. Picture what it will feel like to get that A. Translate that vision into specific, reasonable goals and work toward each individual goal. Take one step at a time and reward yourself for each goal you complete.

- It’s all about you! Don’t waste your time comparing yourself to other students in the class, especially during the exam. Keep focused on your own work and your own plan. Exams are not a race, so it doesn’t matter who turns in their paper first. Certainly, you have no idea how they did on their exam, so a thought like “Kristen is already done, she must have aced it, I wish I had her skills” is counterproductive and will only cause additional anxiety.

- Have a plan and follow it. As soon as you know that an exam is coming, you can develop a plan for studying. As soon as you get your exam paper, you should develop a plan for the exam itself. We’ll discuss this later in this chapter. Don’t wait to cram for an exam at the last minute; the pressure you put on yourself and the late-night will cause more anxiety, and you won’t learn or retain much.

- Make sure you eat well and get a good night’s sleep before the exam. Hunger, poor eating habits, energy drinks, and lack of sleep all contribute to test anxiety.

- Chill! You perform best when you are relaxed, so learn some relaxation exercises you can use during an exam. Before you begin your work, take a moment to listen to your body. Which muscles are tense? Move them slowly to relax them. Tense them and relax them. Exhale, then continue to exhale for a few more seconds until you feel that your lungs are empty. Inhale slowly through your nose and feel your ribcage expand as you do. This will help oxygenate your blood and reenergize your mind.

- Come early and prepared. Come to the exam with everything you need like your pencils, erasers, calculator, etc. Arrive to class early so you aren’t worried about time. Try to avoid the pre-exam chatter of your classmates, as this may contribute to your anxiety. Instead, pick your favorite chair and focus on relaxing.

- Put it in perspective. Take a minute to think about the three most important things in your life. They may be your family, your health, your friendships. Will you lose any of these important things as a result of the exam? An exam is not life or death and it needs to be put in perspective.

Health and wellness cannot be overstated as factors in test anxiety. Studying and preparing for exams can be easier when you take care of your mental and physical health.

Attributions

College Success Author: Amy Baldwin Provided by: OpenStax Located at: https://openstax.org/details/books/college-success License: CC BY 4.0

Testing Strategies in EDUC 1300. Authored by: Linda Bruce. Provided by: Lumen Learning. Located at: https://courses.lumenlearning.com/sanjacinto-learningframework/chapter/testing-strategies. License: CC BY 4.0

References

Aagaard, J. (2019). Multitasking as distraction: A conceptual analysis of media multitasking research. Theory & Psychology, 29(1), 87–99. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354318815766

Dietz, S. & Henrich, C. (2014). Texting as distraction to learning in college students. Computers in Human Behavior, 36, 163-167. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.03.045

Ellis, Y., Daniels, B. & Jauregui, A. (2010). The effect of multitasking on the grade performances of business students. Research in Higher Education Journal, 8, 1-10. Retrieved from https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1595375

Fox, A. B., Rosen, J. & Crawford, M. (2009). Distractions, distractions: Does instant messaging affect college students’ performance on a concurrent reading Comprehension Task? Cyber Psychology and Behavior, 12(1), 51-53. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2008.0107

Lee, J., Lin, L. & Robertson, T. (2012). The impact of media multitasking on learning. Learning, Media and Technology, 37(1), 94-104. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439884.2010.537664

Srivastava, J. (2013). Media multitasking performance: Role of message relevance and formatting cues in online environments. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(3), 888-895. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.12.023

Rosen, L., Lim, A., Carrier, L. M. & Cheever, N. (2011). An empirical examination of the educational impact of text message-induced task switching in the classroom: Educational implications and strategies to enhance learning. Psicología Educativa, 17(2), 163-177. https://doi.org/10.5093/ed2011v17n2a4

Sana, F., Weston, T. & Cepeda, N. J. (2013). Laptop multitasking hinders classroom learning for both users and nearby peers. Computers & Education, 62, 24-31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2012.10.003