8 How did Black Americans in Maxville Experience Joy in an Exclusionary Oregon

Nick Tayer

Introduction: Teaching Through Rather Than About

Section 35, Article 1 of the Constitution of the state of Oregon reads as follows:

No free Negro, or Mulatto, not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside, or be within this state, or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein; an the Legislative Assembly shall provide by penal laws, for the removal, by public officers, of all such Negroes, and Mulattos, and for their effectual exclusion from the state, and for the punishment of persons who shall bring them into the state, or employ, or harbor them.”[1]

This provision of the Constitution would not be rescinded until 1926 and yet between the adoption of this Constitution in 1857 and the repeal of that section in 1926 Black Americans would reside, work, and raise their children in Oregon. Maxville[2] was a segregated logging town founded three years prior to the amendment to the Oregon Constitution to allow for Black Americans to reside in the state. The lives and identities of those who came to Maxville broke away from common conceptions of Black American life. By studying it we get a sliver of a vision of what life was like for Black Americans in the rural West during the Great Migration (specifically 1923 – 1943). We also see how a place once forgotten, today a ghost town, can contribute to our conception of race in the West. Instead of industrial workers in cities or sharecroppers in the South in Maxville Black Americans were loggers and pioneers. Their isolation nestled among the lush forests of the Wallowa Valley in northeastern Oregon gave them a measure of freedom unknown to them in Arkansas and Louisiana, where most of them migrated from. Yet there was also a commonality to their experience in the South, segregation was the law in Maxville and the Ku Klux Klan was a political force in Oregon. In fact it was their support, which likely helped Oregon’s then governor, Walter M. Pierce, win the 1922 gubernatorial election. The nearby regional hub, LaGrande, was also a hub of Klan activity. Despite these similarities Pearl Alice Marsh, a professor of Political Science at the University of California – Berkeley, who was born in Maxville and grew up in nearby Wallowa would title her history of Maxville life “But Not Jim Crow”. It would be this tension between oppression and agency that would define Maxville life as dozens of Black American families would come to call it home throughout the 1920s, 30s, and 40s.

Framework

The notable historian and cofounder of the Annales school of history Marc Bloch once wrote, “When all is said and done, a single word, “understanding”, is the beacon of light in our studies.”[3] If understanding is the historian’s goal then the historian must occasionally seek guidance from others in order to gain this understanding. For our study of Maxville we will be adopting LaGarrett King’s Black Historical Consciousness approach to history. King is a professor of Black American studies at the University of Buffalo and developed this framework to specifically address shortcomings in the study of Black American history. Specifically his view that Black American history was either focused solely on oppression without reference to achievement or that Black American history was amalgamated into whiggish narratives of the United States national history with Black Americans placed on the periphery rather than at the center of that narrative. It is founded upon breaking the Black American experience down into six themes; power and oppression, agency, resistance, and perseverance, the African diaspora, joy, identities, and contention.[4] Studying each of these themes of Black American history has value in understanding the place and experiences of Black Americans in the history of the American West. However, when considering the experiences of the Black Americans who came to Maxville we will focus on two of these six themes. Black Agency, Resistance, and Perseverance, Oregon being a state founded upon the exclusion of Black Americans is but one example of the use of power to oppress Black Americans in the West. Also present in Eastern Oregon at this time was a resurgent Klu Klux Klan. How these factors impacted Black Americans in Maxville and how they resisted and preserved in the face of that oppression is the first theme that studying Maxville allows us to explore. Black Joy is another theme of Black American life which studying Maxville allows us to explore. Maxville had a company baseball team which unlike its Southern counterparts was allowed to play integrated when playing away from Maxville and was allowed to play against White teams. This is just one example of ways in which the Black Americans of Maxville found joy and pride in their daily existences that we will investigate. Before we explore these themes and how they played out in Maxville we must first understand why Maxville came to exist at all.

Pedagogical Applications

When we teach about history we have a content goal, when we teach through history we have a thinking goal, and this lesson is built around a thinking goal. The objective for students in this inquiry lesson is to be able to think about what joy is and how the circumstances beyond our control may limit our access to joy but struggles to eliminate it completely. Teaching through history rather than about it is also about accessing and using sources, both primary and secondary. This lesson relies on three sources; the Oregon Constitution, Pearl Alice Marsh’s “But Not Jim Crow: Family Memories of African American Loggers of Maxville, Oregon”, and the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center which was founded and directed by Gwen Trice. Marsh and Trice are Black American women who are the descendants of loggers of Maxville, who were born and raised in nearby Wallowa shortly after the Maxville logging operation shut down. Both have engaged in extensive interviews with the surviving workers of Maxville to give us insight into what life was like for those living there.

| Essential Question | How did Black Americans in Maxville experience joy in an exclusionary Oregon? |

|---|---|

| Standards | HS.66: Examine & analyze the multiple perspectives & contributions of ethnic & religious groups as well as traditionally marginalized groups within a dominant society & how different values & views shape Oregon, the United States, & the world. |

| Staging | What does Section 35, Article 1 of the Oregon Constitution mean? |

| Supporting Question 1 | What barriers to experiencing joy did Black Americans face in and around Maxville? |

| Formative Performance Task | Describe the barriers Black Americans faced based on analysis of an historical essay on life at Maxville. |

| Featured Sources | Resistance to oppression in Maxville essay. |

| Supporting Question 2 | What did Black joy in and around Maxville look like? |

| Formative Performance Task | List ways in which Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville based on analysis of photographs. |

| Featured Sources | Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center photos. |

| Supporting Question 3 | In what ways were Black Americans able to experience joy in and around Maxville? |

| Formative Performance Task | List ways in which Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville based on analysis of interviews. |

| Featured Sources | Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center interview excerpts. |

| Summative Performance Task | Students will compose a 500 word essay or project of equivalent rigor answering the essential question. |

| Potential Civic Engagement | Oregon History Day Project on either Maxville, Black joy, or Black Americans during exclusion in Oregon. |

Lesson Narrative

Overview and Description of the Essential Question

In this lesson students will examine and analyze the perspectives and contributions of Black Americans in the community of Maxville, Oregon. Specifically students will explore how that community experienced joy in an Oregon that legally prohibited their existence. Students will examine several primary sources from the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center as well as a historical essay and the Oregon constitution.

Staging the Question

Procedure

- Read the passage from the Oregon State Constitution: Section 35, Article 1

- Have students identify key words from the passage.

- Example response: free Negro, Mulatto, residing, adoption, constitution, state, real estate, contracts, maintain, suit, Legislative Assembly, penal laws, removal, public officers, exclusion, punishment, bring, employ, harbor

- Have students utilize those words to create a sentence that summarizes the passage.

- Example response: The constitution stated that no free Negro or Mulatto, who was not residing in the state at the time of its adoption, could come to reside, hold real estate, make contracts, maintain suits, or even be within the state; and the Legislative Assembly had the power to pass penal laws for their removal and exclusion from the state, as well as punish those who brought them into the state, employed or harbored them.

- Have students summarize the passage in their own words.

- Example response: The law says that African Americans who weren’t living in this state before the constitution was made can’t live here, buy property or make any agreements. The government will use the police to kick out black people who are here illegally and punish those who bring them here.

Oregon State Constitution: Section 35, Article 1 & Student Assignment Template

Section 35, Article 1 of the Constitution of the state of Oregon reads as follows:

No free Negro, or Mulatto, not residing in this state at the time of the adoption of this constitution, shall come, reside, or be within this state, or hold any real estate, or make any contracts, or maintain any suit therein; an the Legislative Assembly shall provide by penal laws, for the removal, by public officers, of all such Negroes, and Mulattos, and for their effectual exclusion from the state, and for the punishment of persons who shall bring them into the state, or employ, or harbor them.”

Key Words:

Summary:

In your own words:

Question 1, Formative Task 1, Featured Sources

- Read the essay Resistance to oppression in Maxville. Depending on the class this can be done individually, in pairs, as a class, or as a jigsaw.

- Have students answer each critical thinking question individually.

Analyzing the essay: Resistance to oppression in Maxville

Although Maxville sprang forth from the forest it was not born with a blank slate. Wallowa county had a well established history of exclusion of all non-whites from its founding. Maxville itself sat along the seasonal rounds of the Wallowa band of the Nez Perce Indians. That band had been forcibly relocated to Idaho after confusion over the geography of a reservation in the area combined with local pressure led to that reservation being terminated and resulted in Chief Joseph leading that band on its attempted escape to Canada.[5] This had “opened” the county to settlement and led to its becoming a county in its own right separate from nearby Union county. This was not the end of violent exclusion in the area. In 1887 a local criminal gang massacred thirty-four Chinese miners near Deep Creek in Hells Canyon with the express intent of ensuring that any gold found in the area would be possessed by Whites.[6] Beyond that history Wallowa county was also party to the rising tide of racism in the United States which followed World War I.

Long before the arrival of Maxville and its Black American loggers Wallowa county newspapers had been republishing racist cartoons and articles from around the country. Marsh found an 1895 article that decried the, “flood of negro talk that has discolored recent literature” with later articles advertising minstrel shows or including jokes made at the expense of the country’s Black American population.[7] To give one an idea of how opposed to the introduction of Black Americans to the county residents were believed to be when Henry Ashby the foreman of the logging operation at Maxville went to greet his incoming Black American workers with armed guards for fear of a possible attack by the local Klu Klux Klan.[8] Given such examples of the prevailing attitudes of the area that such an incident was avoided is remarkable.

That Ashby was willing to place his life on the line was not a singular occurrence but nor did it mean that he and the community had shed all of its institutions of oppression that it had inherited from the South. “Bowman Hicks drew racial lines and housing and education out of its own tradition as a Southern town and perhaps to appease some Southern white workers living in Maxville.”[9] This appeasement took the form of segregated schools, segregated housing, segregated baseball teams, and preferential housing for White workers. That preference extended specifically to whether or not one got an actual house at all. White workers and their families had houses and cabins built for them. Black American families and the few Greek immigrants and their families in Maxville were assigned to railcars repurposed as housing. This is at a place where snow is commonly measured in feet rather than inches during the winter, where the rains of spring last past the 4th of July and cool autumn winds begin to blow in early September. However, there were also some accommodations made to the realities of this new life that lead to some integration.

Most apparent to the workers was the willingness of their White colleagues to oppose the local Klan and support the right to live and work in Oregon. Relations with the Klan were tense, not only did Ashby meet each group of Black American migrants to Maxville with an armed guard out of fear of an attack but armed guards were also utilized initially to protect workers in the forest.[10] Even with such precautions, worry over what the Klan might do pervaded operations at Maxville until the potential conflict came to a head. Alan Dale Victor a White resident of Maxville related the following story in an interview with Gwen Trice of the Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center:

Well, it would probably be about the middle ‘20s–a group of Klu Klux Klan members with their hoods on showed up at Maxville. MacMillan, who was the superintendent, and Jim Criley, who was the woods boss, they told them to get the hell out of Maxville. They said, don’t you people ever come back. Jim Criley (sp?) says, maybe you guys have a mask to fool us, but he said, I know who you are. He said I don’t ever want to see your face around here again.[11]

This ended the threat of the Klan but it didn’t mean a complete end to conflict. Although housing, education, and baseball were segregated nearly everything else was integrated. As a result workers shopped together, played together, and often worshiped together. “Bonds between black-and-white loggers were forced for practical reasons integrated labor processes of the timber enterprise in the woods and the danger of the work meant they depended on one another for their safety.”[12] Eventually even the baseball team was integrated for the purpose of playing other teams in the region but there was one line which could never be crossed. “While the family’s experienced new personal liberty there were still social realities of racism in the schools physically segregated housing and little tolerance for interracial romantic relationships.”[13] Oregon followed the South and much of the rest of the nation in outlawing marriages between Whites and Black Americans. Ester Wilfong recounted her brother’s dating experiences, “these were the girls who had to live in that town where they weren’t willing to run the risk of social ostracism by their parents or that their parents would be socially ostracized.”[14] Not only might one be ostracized but also one risked outright violence. Joseph Hillard Jr. is recounted by Marsh as having one incident in which that threat of violence was made explicit:

A friend had been dating a local white girl and not doing a good enough job of covering his tracks. When her mother found out she was dating this black kid named junior, she did some sleuthing and determined incorrectly that I was the culprit. So she called dad and told him he would find me hanging in a tree if I didn’t stop dating her daughter.[15]

This wasn’t the only threat, dances often became a focal point of potential violence as young men would seek out companionship but as a result of these threats most such men dated women from Pendleton or Walla Walla or left Eastern Oregon to find their significant others. The young women had similar frustrations and sought similar remedies. Across the thirty years there would be only one instance where an interracial relationship resulted in marriage, and that required the happy couple to travel to Washington state to circumvent Oregon law prohibiting such a marriage. Over time this resulted in more and more families moving away from Maxville, usually to either nearby LaGrande or to Portland, in search of greater connection with the Black American community.

Critical thinking question 1:

What is the major claim being made by the author of this essay?

What textual evidence supports the author’s claim?

Does the claim that is being presented appear to be fact based or opinion based?

Critical thinking question 2:

What is the “feel” or attitude of the essay?

Give evidence of the “feel” or attitude taken from this essay:

How does this affect the essay’s effectiveness?

Critical thinking question 3:

What are the most convincing or thought-provoking parts of the essay?

Cite textual evidence to support your opinion:

Example Responses

Critical thinking question 1: What is the major claim being made by the author of this essay?

Maxville, a logging town in Oregon, was founded in a region with a history of exclusion and racism towards non-white populations and its African American population struggled in the face of that oppression.

What textual evidence supports the author’s claim?

- The Wallowa band had been forcibly relocated to Idaho

- a local criminal gang massacred thirty-four Chinese miners

- the foreman of the logging operation at Maxville went to greet his incoming Black American workers with armed guards for fear of a possible attack by the local Klu Klux Klan

- segregated schools, segregated housing, segregated baseball teams, and preferential housing for White workers

- little tolerance for interracial romantic relationships

Does the claim that is being presented appear to be fact based or opinion based?

Fact based: each piece of evidence is either sourced from historians or from eye witness accounts.

Critical thinking question 2: What is the “feel” or attitude of the essay?

The attitude of the essay is one of informed neutrality.

Give evidence of the “feel” or attitude taken from this essay:

- “Bonds between black-and-white loggers were forced for practical reasons. Integrated labor processes of the timber enterprise in the woods and the danger of the work meant they depended on one another for their safety.”

- While the family’s experienced new personal liberty there were still social realities of racism in the schools’ physically segregated housing and little tolerance for interracial romantic relationships.”

How does this affect the essay’s effectiveness?

It weighs the scales towards oppression being the dominant force in their lives.

Critical thinking question 3: What are the most convincing or thought-provoking parts of the essay?

The balance between willingness to allow them to live their own lives with the unwillingness to fully integrate. Colleagues were fine, maybe even friendships, but the essay draws a clear line at romance.

Cite textual evidence to support your opinion:

- Well, it would probably be about the middle ‘20s–a group of Klu Klux Klan members with their hoods on showed up at Maxville. MacMillan, who was the superintendent, and Jim Criley, who was the woods boss, told them to get the hell out of Maxville. They said, don’t you people ever come back. Jim Criley (sp?) says, maybe you guys have a mask to fool us, but he said, I know who you are. He said I don’t ever want to see your face around here again.

- A friend had been dating a local white girl and not doing a good enough job of covering his tracks. When her mother found out she was dating this black kid named junior, she did some sleuthing and determined incorrectly that I was the culprit. So she called dad and told him he would find me hanging in a tree if I didn’t stop dating her daughter

Answers will vary to questions 2 and 3. Teachers should be open to a variety of conclusions regarding both the tone and what evidence students find most convincing. These can be addressed either in a class discussion or in a think-pair-share style conversation.

Question 2, Formative Task 2, Featured Sources

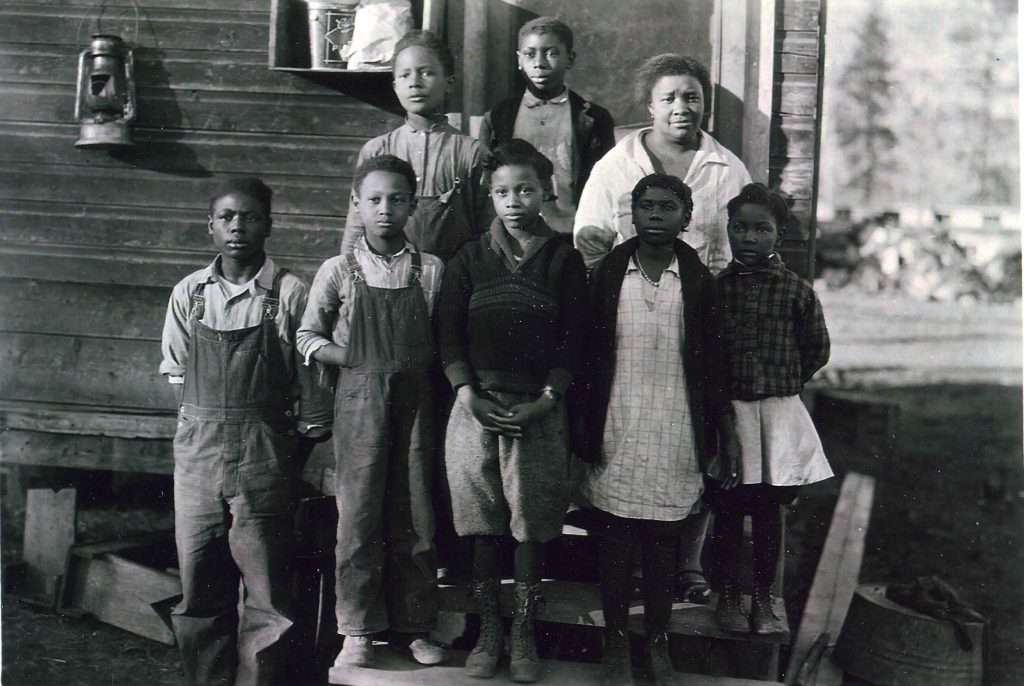

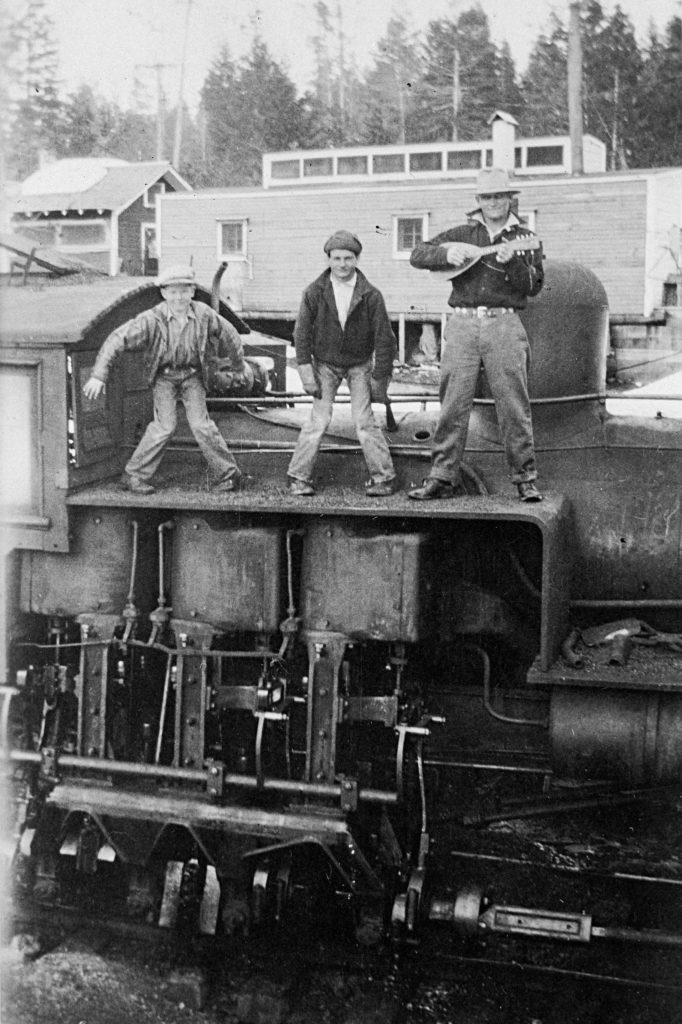

For each of the images in this task the procedure is the same. Example responses are provided beneath each image. The procedure assumes that the images are shared with the class via projector/tv/smart board but they don’t have to be. This procedure also assumes a pair-share model of instruction but can be modified for groups or done strictly individually.

- Display the image to the class.

- Have students individually list who is in the photograph.

- Have students share their list with a partner, noting any differences.

- Have a pair of students share their list with the class. Ask for any additional people noticed by students.

- Have students individually write a sentence describing just the people in the photograph.

- Have students individually list what is in the photograph.

- Have students share their list with a partner, noting any differences.

- Have a pair of students share their list with the class. Ask for any additional people noticed by students.

- Have students individually write a sentence describing just the objects in the photograph.

- Have students individually list actions in the photograph.

- Have students share their list with a partner, noting any differences.

- Have a pair of students share their list with the class. Ask for any additional people noticed by students.

- Have students individually write a sentence describing just the actions in the photograph.

- Finally have students synthesize into a sentence concluding how the photograph could be used as evidence of Black Americans experiencing joy around Maxville, Oregon.

Response Template

People

Details: list who is in the photograph.

Describe: write a sentence describing the people in the photograph.

Objects

Details: list what is in the photograph.

Describe: write a sentence describing an object in the photograph.

Activity

Details: list what is happening in the photograph.

Describe: write a sentence describing what is happening in the photograph.

Assessment

What does this photograph tell you about how Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville?

Example Response

People

Details: list who is in the photograph.

7 children and their mother?

Describe: write a sentence describing the people in the photograph.

Answers may vary.

Objects

Details: list what is in the photograph.

Oil lantern, Wash basin, Stool, Cabin? (Actually a rail car)

Describe: write a sentence describing an object in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Activity

Details: list what is happening in the photograph.

Family photograph

Describe: write a sentence describing what is happening in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Assessment

What does this photograph tell you about how Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville?

Black Americans around Maxville lived hard lives but had the joy of their families.

Example Response

People

Details: list who is in the photograph.

School children and their teachers? Parents?

Describe: write a sentence describing the people in the photograph.

Answers may vary.

Objects

Details: list what is in the photograph.

School building?

Describe: write a sentence describing an object in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Activity

Details: list what is happening in the photograph.

Class photo during the school year

Describe: write a sentence describing what is happening in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Assessment

What does this photograph tell you about how Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville?

Black Americans were excluded from education and would have struggled to experience the joy that comes from education.

Example Response

People

Details: list who is in the photograph.

2 white women, 2 white teenagers, 2 black women, 2 black boys, 1 black infant

Describe: write a sentence describing the people in the photograph.

Answers may vary.

Objects

Details: list what is in the photograph.

Clothes, shacks, cabins

Describe: write a sentence describing an object in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Activity

Details: list what is happening in the photograph.

Sitting together for a staged photograph

Describe: write a sentence describing what is happening in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Assessment

What does this photograph tell you about how Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville?

Black families were able to experience joy by forming friendships with white families.

Example Response

People

Details: list who is in the photograph.

3 white men

Describe: write a sentence describing the people in the photograph.

Answers may vary.

Objects

Details: list what is in the photograph.

Fiddle, locomotive

Describe: write a sentence describing an object in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Activity

Details: list what is happening in the photograph.

Dancing, playing music

Describe: write a sentence describing what is happening in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Assessment

What does this photograph tell you about how Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville?

Black Americans around Maxville were excluded from participating in dancing with their white neighbors.

Example Response

People

Details: list who is in the photograph.

20 people looks like both white and black

Describe: write a sentence describing the people in the photograph.

Answers may vary.

Objects

Details: list what is in the photograph.

Cars, Baseball field, Baseball equipment

Describe: write a sentence describing an object in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Activity

Details: list what is happening in the photograph.

People are playing baseball.

Describe: write a sentence describing what is happening in the photograph.

Answers may vary

Assessment

What does this photograph tell you about how Black Americans experienced joy in and around Maxville?

Black Americans around Maxville experienced joy playing baseball with each other.

Question 3, Formative Task 3, Featured Sources

Procedure

- Read the passage of the interview with Bob Chrisman

- Have students identify key words from the passage.

- Have students utilize those words to create a sentence that summarizes the passage.

- Have students summarize the passage in their own words.

Interview with Bob Chrisman

The only thing that I know is, again, definitely second hand from my father and my uncle Verd Baird that had Baird’s Tavern down here. I guess nobody could beat them. They had the best baseball team in the whole area. Big Amos was just an amazing athlete. I guess he was just something else. I can remember looking at that guy–my gosh, he was just a perfect person when it came physically, just this big, strong man. I guess he ran fast. My uncle Verd, he played a lot of baseball. They had the town team, baseball teams and whatever. He said, ah, we quit playing them–they just beat us so bad. I do know they won about every game they ever played. But that’s all I really know about that.

Example Response

Key Words:

Second hand, Father, Uncle ,Baird’s Tavern, Baseball team, Big Amos, Athlete

Perfect person ,Physically strong ,Town team, Won every game

Summary:

According to what he was told second hand by his father and uncle, the baseball team, led by the physically strong and impressive athlete Big Amos, was unbeatable and won every game.

In your own words:

The passage is about the speaker’s second-hand knowledge from their father and uncle about the Maxville baseball team, which had the best baseball team in the area led by the amazing athlete Amos Marsh. The team won every game, and the speaker describes Amos as a physically perfect person. The uncle had played baseball and had to quit because they couldn’t beat the Maxville team.

Procedure

- Read the passage of the interview with Mattie Langford Wilfong.

- Have students identify key words from the passage.

- Have students utilize those words to create a sentence that summarizes the passage.

- Have students summarize the passage in their own words.

Interview with Mattie Langford Wilfong

Well, we would embroidery and like that. Mostly, we had something to do we would bring over, and we would read the Bible. Most all of us—some of us knitted. I did embroidery work. We did little things, you know, like that together. But, other than that, and you see we would have what we called our little church, because we didn’t go to—there was no church or nothing. No church there and everything, and so I really don’t remember at all going to church in Wallowa. We just—we had a little church there, reading the Bible certain days and we called it our Bible week and like that and Sunday ourselves.

Example Response

Key Words:

Embroidery, Bible, Knitted, Little things ,Church, Wallowa, Bible week, Sunday

Summary:

They had a little church where they would read the Bible and called it Bible week, and on Sundays, they held services themselves since there was no church in Maxville.

In your own words:

The passage describes how the speaker and others in Maxville had no church to attend, so they gathered to do embroidery, knitting, and read the Bible together. They called it their little church and had a Bible week where they would read the Bible on certain days, and on Sundays, they held their own services.

Procedure

- Read the passage of the interview with Ester Wilfong Jr

- Have students identify key words from the passage.

- Have students utilize those words to create a sentence that summarizes the passage.

- Have students summarize the passage in their own words.

Interview with Ester Wilfong Jr. Part 1

In looking at Wallowa, that’s where most of the minority folks who were in the area lived. It was because of the work that they were doing as being hired to work in that area. So dad was out in the woods felling trees and would come home on the weekends to be with the family. I got to the town of Promise, that I remember, early while we were there. Being a child, you don’t look at things as adults do. You don’t see as much as adults do, so you would pass over some things. But I did remember myself and my parents and Joe Patterson, Jr. and his wife, Helen. We went up to Promise to some function, and while there, there was a dance going on. We just sat and watched the people dancing–a different kind of dancing that what Joe and Helen had done–but they did get up and do a little number or two, but it all went well. Then that’s my biggest thing–I remember except going up there once again when Bob Baggett, who was African American and lived there, and he was sort of overseer–somewhat of part of the area–I am not sure, but anyway we went up there to visit with him and his wife, Lillian…

Example Response

Key Words:

Wallowa, minority folks, hired work, dad, woods, felling trees, weekends, family, Promise, child, Joe Patterson Jr., Helen, function, dance, different kind of dancing, Bob Baggett, African American, overseer, visit, Lillian.

Summary:

While living in Wallowa, my dad worked in the woods felling trees and would come home on the weekends to be with our family; as a child, I remember going up to Promise with my parents, Joe Patterson Jr. and his wife, Helen, for a function where we watched a different kind of dancing and later visited Bob Baggett, an African American overseer, and his wife, Lillian.

In your own words:

The passage describes the narrator’s memories of growing up in Wallowa, where most of the Black Americans lived and worked. The narrator recalls going to Promise as a child, where they attended a dance and visited Bob Baggett, an African American overseer in the area. Despite being a child, the narrator still remembers these experiences vividly.

Procedure

- Read the passage of the interview with Ester Wilfong Jr., Part 2

- Have students identify key words from the passage.

- Have students utilize those words to create a sentence that summarizes the passage.

- Have students summarize the passage in their own words.

Interview with Ester Wilfong Jr., Part 2

Oh, there was no dating. This was way back then. If it was dating, it was on the side, that nobody knew about, and the after hours kinds of thing that you have to sneak around to do because those were the white girls–there weren’t that many African American girls there. Most of them were younger than I, so there wasn’t any dating to speak of. There were things that happened, but they weren’t the things that came out in the open. And that might be one of the reasons why that we got along because we were not dating the white girls. I would go to the dances and dance, but Bob and Jim–they were ahead of me both, and they didn’t go to the dances. Once we got to college, I went to the dances there and I did some dating in college, but not in high school because these were the girls who had to live in that town where they weren’t willing to run the risk of social ostracism by their parents or that their parents would be socially ostracized…

Example Response

Key Words:

dating, white girls, African American girls, after hours, sneak around, younger, things happened, social ostracism, college, dances

Summary:

Most African American boys in the town refrained from dating white girls due to social ostracism and the limited availability of African American girls in the area

In your own words:

The passage describes how dating was not common in the speaker’s high school due to the limited number of African American girls and societal pressures. The speaker and their friends did not date white girls and engaged in after-hours activities that were kept secret. The speaker did attend dances but did not date until college. The lack of dating in high school may have contributed to their strong friendships.

Procedure

- Read the passage of the interview with Ester Wilfong Jr., Part 2

- Have students identify key words from the passage.

- Have students utilize those words to create a sentence that summarizes the passage.

- Have students summarize the passage in their own words.

Interview with Ester Wilfong Jr., Part 3

The men who worked in the woods in Wallowa, a number of them lived in Maxville. Some of the families lived there in Wallowa, and dad had wanted us to live in La Grande where he thought there was a better schooling there that I could receive. So, he would come home on the weekends. That’s the time that I would see my father more. I didn’t see him during the week except in the wintertime when it was too cold to go out into the woods. So the experiences that we had were not so much dad and son. He loved to hunt, but I didn’t go hunting with him that much because he didn’t get a chance to hunt that much himself. I did go out a few times, but shooting a deer might be fine for him but I didn’t want to kill a deer. I have always said if you gave those deer a rifle and they could shoot back, there wouldn’t be as many hunters out there. But that’s factitious. No, I was really not a hunter, although I could shoot a rifle fairly well.

Example Response

Key Words:

Wallowa, Maxville, La Grande, schooling, father, weekends, hunting, experiences, son, deer, rifle.

Summary:

Dad worked in the woods in Wallowa and would come home on the weekends, but since it was too cold to work during the winter, I didn’t get to see him as often except when we went hunting together.

In your own words:

The passage describes the relationship between a father and son who lived apart during the week because of the father’s work in the woods. The father wanted his son to receive a better education in La Grande, so he would come home on weekends. Despite the father’s love for hunting, the son did not share his enthusiasm for killing animals.

Optional Summative Performance Task

Students will compose a 500 word essay or project of equivalent rigor answering the question, “How did Black Americans in Maxville experience joy in an exclusionary Oregon?” The Oregon Department of Education official Social Science analysis scoring guide should be used to score the resulting project or essay.

Potential Civic Engagement

Oregon History Day Project on either Maxville, Black joy, or Black Americans during exclusion in Oregon.

Conclusion

By the end of World War II Maxville had ceased to exist as a town. Some of its residents had moved to nearby Wallowa or LaGrande. Many of the Black American logging families traded in their saws for welders at the Kaiser Shipyard in Portland joining a great influx of Black Americans to the city that would increase their population from just under two thousand, in the twenties, thirties, and forties to over nine thousand by 1950.[16] Nearly eight thousand of whom were employed by those shipyards alone.[17] In this sense Maxville was merely a waypoint on those families’ migration from the South similar to how Portland would be a waypoint for over half of the twenty thousand Black Americans who came to work there during World War II but moved on after the war.[18] Many of the houses in Maxville were moved to Wallowa where they provided housing for workers at the new lumber mill there.

Maxville was neither the first, nor the largest segregated community in Oregon. It was however an unusual presence in the state’s northeast corner where the Klu Klux Klan dominated local politics and its largest community had a sundown law on the books prohibiting Black Americans from staying within city limits after dark. It wasn’t unique in its experience of oppression but it also didn’t fit the norms of the era in that integration came long before the courts or legislation required it. It was a place of hard work, fears, and joys. By looking at it through the framework of a Black Historical Consciousness we have been able to focus on both oppression and joy in the lives of those who came to Maxville. With that we have been able to understand how they were able to exist in a place whose laws said upon their arrival that they were not allowed to be there. How despite that limitation, and the limitations of the racism endemic to that time and place, were able to persevere in the face of such oppression. How that perseverance allowed them to resist the bleakness such an existence might have had and instead find joy in their lives. In Maxville they were segregated, and faced threats of lynching, but were never lynched. They raised families and played baseball. They enjoyed plentiful fish and game that the forests they worked in provided. Then they took what meager wealth the rigor and danger of logging had afforded them and moved on to places that would afford their children the opportunity to raise families of their own.

Image Attributions

[Photograph of students and teacher posing in front of Maxville’s segregated Black school] (1926). Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://maxville.squarespace.com/timber-culture-gallery/9i5a3au5xb0eopg8dta4etjp5sx3um. Public domain (CC0).

[Photograph of students and teachers posing in front of Maxville’s White-only school building] (1926). Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://maxville.squarespace.com/timber-culture-gallery/tk11l6oby6yte5w8hkrlrmkathkkt8. Public domain (CC0).

[Photograph of a small group of Black and White children of various ages posing together after desegregation] (1937). Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://maxville.squarespace.com/timber-culture-gallery/1mz6bcjea78rvjn8aou0yn80e0fnmc. Public domain (CC0).

[Photograph of two men and one boy atop a steam locomotive used to transport lumber] (1923). Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://maxville.squarespace.com/timber-culture-gallery/ns1fkp8z6m7mfk7lsbbbxp5ur3qb8c. Public domain (CC0).

[Photograph of the Maxville Wildcats, an integrated local baseball team] (1925). https://maxville.squarespace.com/timber-culture-gallery/shymi0y2c7vo4u1aez5h30zd7wyxpp. Public domain (CC0).

Resources

Primary Sources

Oregon Secretary of State (n.d.). Transcribed 1857 Oregon Constitution. https://records.sos.state.or.us/ORSOSWebDrawer/Recordhtml/9479967

Trice, G. (n.d.). Bob Chrisman [Interview]. Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/bob-chrisman-maxville-elder-interview

Trice, G. (n.d.). Jim Henderson [Interview]. Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/jim-henderson-maxville-elder-interview

Trice, G. (n.d.). Ada Metsopulos [Interview]. Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/ada-metsopulos-maxville-elder.

Trice, G. (n.d.). Alan Dale Victor [Interview]. Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/alen-dale-victor.

Trice, G. (n.d.). Ester Wilfong Jr. [Interview]. Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/ester-wilfong-jr-maxville-elder-interview.

Trice, G. (n.d.). Mattie Langford Wilfong [Interview]. Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center. https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/mattie-langford-wilfong-maxville-elder-interview.

Secondary Sources

Bloch, M. (1963). The historian’s craft; introduction by Joseph R. Strayer. Knopf.

DuBois, W.E.B. (2008). The souls of Black folk. Oxford University Press.

Highberger, M. (2003). The town that was Maxville. Bear Creek Press.

Horsman, R. (2006). Race and manifest destiny: the origins of American racial Anglo-Saxonism. Harvard University Press

Katz, W. L. (1973). The Black west: a pictorial history. Doubleday.

Katz, W. L. (1986). Black Indians: a hidden heritage. Simon & Schuster, 1986.

Katz, W. L. (2017). Black pioneers: an untold story. African Tree Press.

Marsh, P. A. (2019). But not Jim Crow: family memories of African American loggers in Maxville, Oregon. African American Loggers Memory Project.

Steber, R (2013). Red White Black: a true story of race and rodeo. Self-published.

Taylor, Q. (1999). In search of the racial frontier: African Americans in the American west, 1528-1990. W. W. Norton & Company.

Journal Articles

Bussel, R., & Tichenor, D. J. (2017). Trouble in paradise: a historical perspective on immigration in Oregon. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 118(4), 460–87. https://www.ohs.org/oregon-historical-quarterly/back-issues/upload/Bussel-and-Tichenor_Trouble-in-Paradise_OHQ-118_4_Winter-2017_web.pdf.

Horowitz, D. A. (1989). Social morality and personal revitalization: Oregon’s Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 90(4), 365–84. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20614269.

Horowitz, D. A. (1992). The ‘Cross of Culture’: La Grande, Oregon, in the 1920s. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 93(2), 147–67. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20614450.

King, L. (2020). Black history is not American history: toward a framework of black historical consciousness. Social Education, 84(6),335–41. https://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/view-article-2020-12/se8406335.pdf.

McCoy, R. R. (2009). The paradox of Oregon’s progressive politics: the political career of Walter Marcus Pierce. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 110(3), 390–419. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20615986.

Smith, S. L. (2014). Oregon’s Civil War: the troubled legacy of emancipation in the pacific northwest. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 115(2), 154–73. https://www.ohs.org/oregon-historical-quarterly/upload/02_Smith_Oregon-s-Civil-War_115_2_Summer-2014.pdf.

Toy, E. (2006). Whose frontier? The survey of race relations on the pacific coast in the 1920s. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 107(1), 36–63. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20615610.

Trice, G., Martínez, G., & Ho., S. (2017). Migration public history: a roundtable discussion at the Oregon migrations symposium. Oregon Historical Quarterly 118(4), 598–611. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5403/oregonhistq.118.4.0598.

Collections

Oregon Secretary of State (2021). Initiative, referendum, and recall introduction. Oregon Blue Book. https://sos.oregon.gov/blue-book/Pages/state/elections/history-introduction.aspx.

Milner, C. A. (2002). Major problems in the history of the American West: documents and essays. Houghton Mifflin.

Milner, C. A., O’Connor, C. A., & Sandweiss, M. A. (1997). The Oxford history of the American West. Oxford University Press.

Stickroth, K. (2018). Wallowa County history: a continuation. Wallowa County Museum Board.

West, E. (2014). The essential West: collected essays. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Charles Henry Carey, “The Oregon Constitution and Proceedings and Debates of the Constitutional Convention of 1857 (pdf),” The Oregon Constitution and proceedings and debates of the Constitutional Convention of 1857 § (1926), https://sos.oregon.gov/archives/exhibits/constitution/Documents/transcribed-1857-oregon-constitution.pdf, 25. ↵

- Maxville’s location can be best observed using the Oregon History Wayfinder. https://www.oregonhistorywayfinder.org/#/articles/oep/1334 ↵

- Marc Bloch, The Historian's Craft; Introd. by Joseph R. Strayer (New York: Knopf, 1963), 143. ↵

- LaGarrett King, “Black History Is Not American History: Toward a Framework of Black Historical Consciousness,” Social Education 84, no. 6 (2020): pp. 335-341, 339.King defined these themes as follows; Power and oppression: “Power and oppression as Black histories are narratives that highlight the lack of justice, freedom, equality, and equity of Black people experienced throughout history.” Black Agency, Resistance, and Perseverance: “Black agency, resistance, and perseverance are Black histories that explain that although Black people have been victimized, they were not helpless victims.” Africa and the African Diaspora: “Africa and the African Diaspora as Black histories stress that narratives of Black people should be contextualized within the African Diaspora.” Black joy: “Black joy narratives are narratives of Black histories that focus on Black people’s resolve during oppressive history.” Black identities: “Understanding Black identities as Black histories promotes a more inclusive history that seeks to uncover the multiple identities of Black people through Black history.” Black Historical Contention: “Black historical contention is the recognition that all Black histories are not positive. Black histories are complex and histories that are difficult should not be ignored.” ↵

- Marsh, 11. ↵

- Marsh, 11. ↵

- Marsh, 10. ↵

- Marsh, 18. ↵

- Marsh, 19. ↵

- Marsh, 17. ↵

- Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center, Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center, accessed July 25, 2022, https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/alen-dale-victor. ↵

- Marsh, 18. ↵

- Marsh, 24. ↵

- Ester Wilfong JR., Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center, Maxville Heritage Interpretive Center, accessed July 5, 2022, https://www.maxvilleheritage.org/oral-history-collection/ester-wilfong-jr-maxville-elder-interview. ↵

- Marsh, 90 ↵

- Quintard Taylor, In Search of the Racial Frontier: African Americans in the American West, 1528-1990 (New York, NY: W. W. Norton & Company, 1999), 254. ↵

- Taylor, 255. ↵

- Taylor, 269. ↵