1 Introduction to New Media Art

What is New Media Art?

Is New Media Art truly “new”? How is New Media Art both different from traditional art forms and informed by art history? What is the distinction between New Media Art and new media? How does New Media Art employ and respond to emerging technologies? In what ways does New Media Art blur the boundaries between the sciences and the arts? How does New Media Art challenge other strict categories, including the supposed separation between art and life and the division between online and “irl” challenged by writer Nathan Jurgenson? Why is New Media Art so difficult to define?

This book explores these questions in multiple ways by proposing a long historical context for the technologies and ideas related to New Media Art in the twenty-first century. In this first chapter, we introduce Elements of New Media Art, which are woven throughout the rest of the book and propose a framework through which we can consider the long history of New Media Art.

Stop & Reflect: New Media Art

Take 5 minutes and write down words, ideas or images that arise for you when you hear the term “New Media Art”.

(Keep in mind that the term combines the concept of New Media with the concept of Art. What do you already know about those two concepts?)

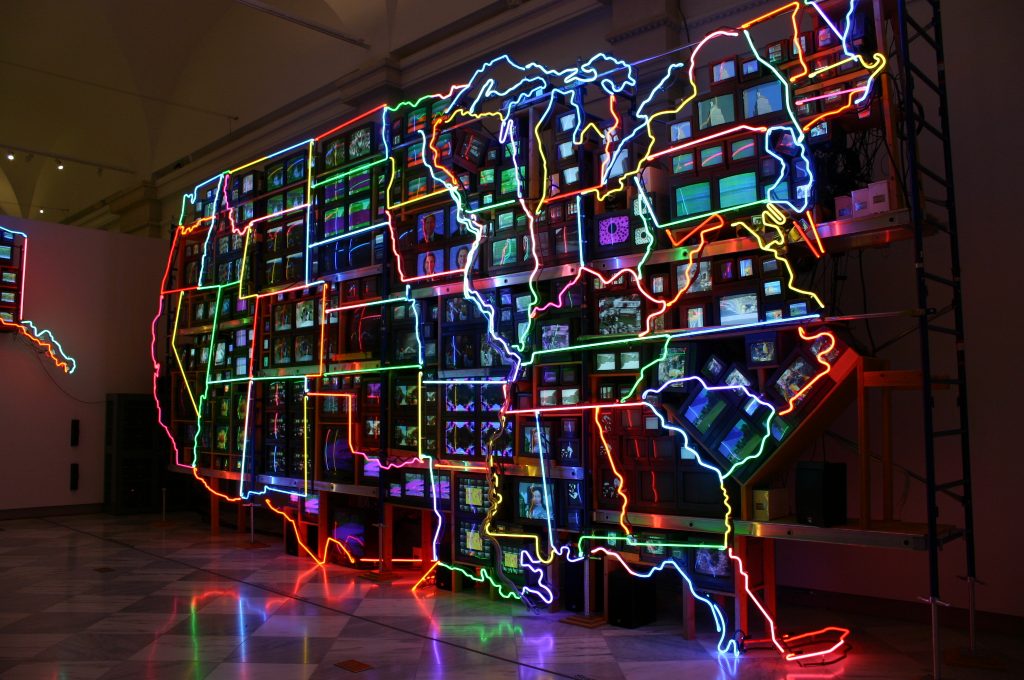

Early New Media artists like Nam June Paik (1932-2006), saw liberatory potential in the many new technologies being introduced in the late twentieth century. Paik and others felt that technology could radically open up the world and give more people a chance to make and share art. Paik even predicted many developments that have shaped the trajectory of New Media Art, including the Internet and video conferencing (à la Zoom).

Others saw potential in digital connection, but Paik identified the communication possibilities of these new technologies. Paik also foresaw the development of video as an artistic medium, the innovation of smart phones and apps, and the rise of global media, arguing that global communication could help unite the world. This last prediction seems heartbreaking in the early 21st century, when the world feels deeply fractured, in large part thanks to the very technologies Paik predicted.

The revolutionary potential of the Internet and other digital technologies that Paik and so many others hoped for throughout the 80s and 90s, might feel lost to us in the early twenty-first century. However, scholar and curator Legacy Russell argues that, despite the fact that the Digital Revolution did not result in the radical social and cultural transformation promised, New Media artists today continue to effectively mobilize via social media and other digital platforms to glitch systems of oppression, challenge the status quo and open new possibilities for interaction and new ways of thinking about what it means to be an artist and a human in this strange, complicated world.

While this textbook is not comprehensive, we aim to explore many artists who have done and are still doing this work. We also plan to continue expanding our exploration in future editions. We have not tried to create a definitive art history of New Media Art because we don’t think that definitive histories are possible or desirable. We have instead tried to create a book in motion, because the field of New Media Art is constantly being constructed. This also means that the Elements of New Media Art that frame this book should not be considered a comprehensive list, but a set of propositions or ways of thinking about approaches to New Media Art.

Elements of New Media Art

- Expands the definition of art

- Democratizes access to art

- Exploits new technology for artistic purposes

- Merges new media with old media

- Readymade – uses objects or material from everyday life

- Remixing – uses images or things made by others in new ways

- Chance – removes the artist’s total control

- Time – unfolds over time

- Ephemeral – isn’t meant to or can’t last forever

- Intangible – not an object, without physical form

- Liveness – happens in real time, the artist is there

- Variable – always different, changing

- Interactive – viewers are involved and can change and manipulate the work

- Collaborative – the artist is a facilitator and viewers make the art with them

- Replicable – can be copied multiple times and exist in different states

- Connectivity – made possible because of new global connections

- Glitch – Challenges the status quo

- (Adapted from work by Lev Manovich, Legacy Russell, Mark Tribe and Susan Morris.)

Stop & Reflect: Elements of New Media Art

- Examine the Elements of New Media Art listed above. Are there examples of art that you’re already familiar with that relate to any of these elements?

- What examples from your own life can you connect to any of these elements?

- What’s a good example of something you have encountered that is ephemeral (not lasting forever)?

- What have you encountered (or enacted) in your life that challenges the status quo? Consider these questions for each one of the Elements of New Media Art and be prepared to share your thoughts with your colleagues if you’re reading this book in preparation for a class discussion.

New Media Art is not new

So, what is New Media Art? By now you know that this question has multiple answers. Some contradict each other and some have yet to be proposed. The word “new” suggests novelty, but many elements of New Media Art were first explored by artists more than a century ago, and some even earlier. So many elements of New Media Art are not really new at all. (See the chapters on Printmaking, Photography and Early Film for some great examples.)

A better way of thinking about the “new” is that New Media Art is labelled such because it is different from more traditional art media like painting and sculpture, which have their origins in Prehistory, more than 30,000 years ago. Painting and sculpture were also the primary art mediums privileged in the concept of “Fine Art” that Europeans invented during The Enlightenment. In developing the concept of Fine Art and the Art Academies that trained artistic professionals, European thinkers misunderstood and marginalized many forms of creative making across the globe. Distinctions between what is art and what is not art were also used to support colonizing expansion and exploitation. The European Art Academies created a hierarchy of artistic mediums and paved the way for the modernist idea of art as an object that is looked at, made by one individual, existing in one space, with only one form and valued for its uniqueness and originality. As we will see, New Media Art offers entirely new ways of thinking about and experiencing art.

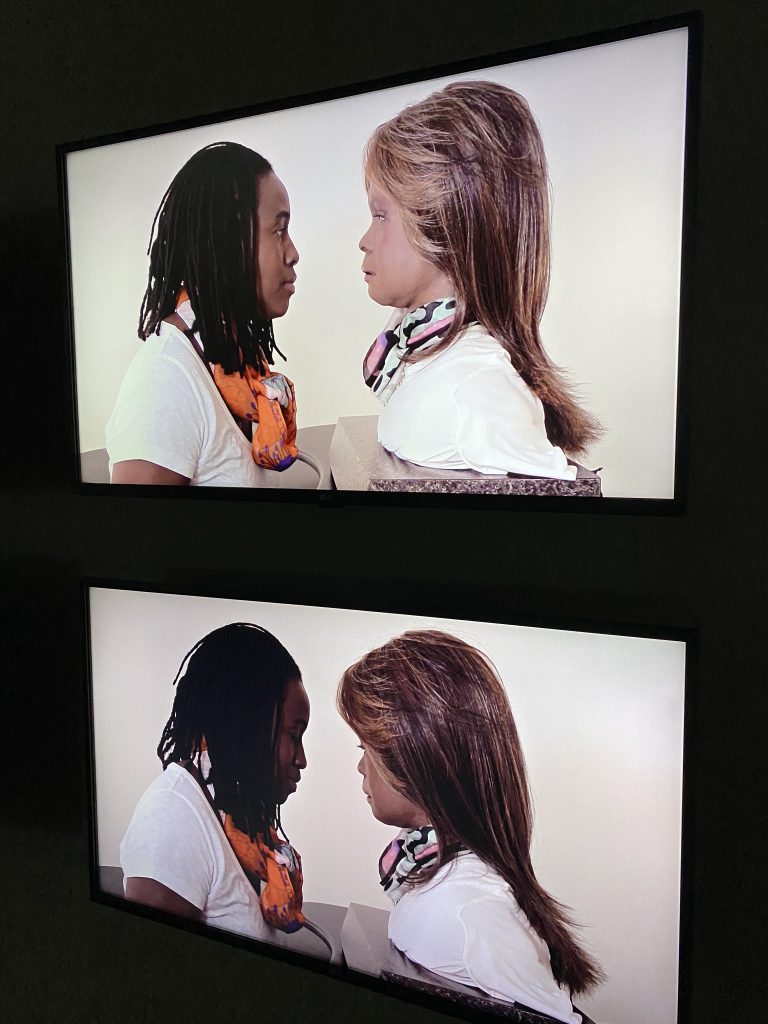

New Media Art encompasses many different approaches to art making, but it is probably most closely associated with art made possible by the new technologies of the Digital Age such as computer-based art, electronic music, social media, digital photography, net art, video games, interactive installation art, and projects employing virtual or augmented reality. One example is the project Conversations with Bina48, initiated in 2014 by the artist Stephanie Dinkins (born 1964). The project involves Dinkins filming conversations she conducts with an intelligent computer named Bina48 (Breakthrough Intelligence via Neural Architecture, 48 exaflops per second). Throughout the conversations covering family, love, race, religion, and robot ethics, Dinkins and Bina48 explore many of the same questions examined by philosophers and artists for millennia. Conversations with Bina48 also considers the complexities of artificial intelligence, algorithmic power and data mining in a racialized and racist world. What happens when the future is being primarily built by white men? In order to address gender and racial inequities in the tech world, the world that is building our future through algorithms, Dinkins has advocated for more access in BIPOC communities to technology and tools for shaping the technological future. In interviews, Dinkins has situated her work in a context prepared by Civil Rights leaders who explained that what we have is not a technology problem, but a race problem. Some New Media Art, like Dinkins’ work, engages critically and meaningfully with this problem.

Elements of New Media Art: Time and Liveness

New Media Art also encompasses art that uses actual time and actual space as design elements, instead of trying to create an illusion of time and space as more traditional art media like painting and sculpture do. This approach includes some of the digital approaches listed above, like Nam June Paik’s work which often blurs the boundaries between sculpture and video art. New Media Art also encompasses the time-based arts of video art, land art, social practices and performance art. Of these approaches, performance art is the only one that usually requires the presence of the artist. Performance art is often ephemeral. A performance happens once and if it is ever reperformed, it is a different work of art because the context and thus the meaning of the work has changed. For example, the artist Lorraine O’Grady (born 1934) started performing her piece, Mlle Bourgeoise Noire in 1980 by attending art openings in New York City unannounced and performing actions including reading poems to the art world attendees. The photograph above is from Mlle Bourgoise Noire’s invasion at the opening of the Persona exhibition at the New Museum in 1981. O’Grady titled this exhibition The Nine White Personae Show and exclaimed the following poem to the audience assembled at the opening:

WAIT wait in your alternate/alternative spaces

spitted

on fish hooks of hope

be polite

wait to be discovered

be proud

be independent

tongues cauterized

at openings no one attends

stay in your place

after all

art is only for art’s sake

THAT’S ENOUGH

don’t you know sleeping beauty needs more than a kiss to awake

now is the time for an INVASION!

O’Grady’s performances are good examples of New Media Art that challenges the status quo, in this case, the marginalization of Black women and artists of color in major museums and New York art galleries. O’Grady herself has explained that she engaged in this performance led by the firm belief that art has the power to change the world. In this sense, O’Grady’s work is an ancestor of the glitch feminist approaches to New Media Art articulated by Legacy Russell.

The Mlle Bourgoise Noire performances also provide a clear example of how ephemeral and context specific performance art can be. O’Grady has noted that after the performances, throughout the 80s and 90s, two iconic photographs were often reprinted and distributed without context and sometimes even without a description of the project. The lack of context contributed to misunderstandings of the work in O’Grady’s view and points to the complexities of trying to write about, study and analyze ephemeral and context specific works of New Media Art.

In the same way that some New Media Art is decontextualized and thus misunderstood, anthropologist David Harvey has argued that technology is often removed from its broader context, its longer history and its cultural impact when it is discussed in the 21st century. This book aims to challenge that mystification of technology, by presenting the long history of New Media Art concepts and engaging with artists who have explored the cultural impacts and the potentials of new technology with their work for centuries.

Elements of New Media Art: Expands the definition of Art

All media were once new media

Because this book is meant as an introduction to New Media Art, we will examine projects that make use of emerging technologies with a focus on projects that are concerned with the cultural, political and aesthetic possibilities of those tools. But we will also examine New Media Art in the broader context of more traditional art media, drawing on the work of New Media theorists like Lev Manovich and others.

The first half of this book introduces a history of technologies that impacted the world of art before the Digital Revolution of the 1990s. We look back this far in order to explore how New Media strategies are part of a much longer history of image making and storytelling. As Lev Manovich has explained, “All media were once new media” and most of the elements of New Media Art we’ll examine in this textbook have precedents in technological innovations of the past. Since the Renaissance in the fifteenth century, artists have been using new intellectual, scientific and technological developments in ways that radically extend the conventional art media of sculpture and painting. So we will examine the convergence of technology, science, art, design and culture since the introduction of movable type printing to Europe in the 15th century, which is where this exploration of New Media Art begins.

Elements of New Media Art: Replicable

In the Printmaking chapter of this textbook, we explore how artists have used new technologies in the past to challenge the status quo and encourage people to see the world around them in exciting new ways. Printing challenged the logic of the traditional art world, by providing the first reliable method for making multiple copies of images and words. Traditional art media assumes a one-of-a-kind art object, made by a single artistic genius and distributed through a set of exclusive galleries, museums or auction houses. In contrast, the logic of New Media Art embraces the existence of numerous copies and many different states of the same work. Moreover, the distribution of New Media Art often bypasses the gallery system. Printing paved the way for these new approaches to artistic media. When the first printing and experiments with movable type were developed in China more than a thousand years ago, average people began to have more exposure to images and words, through objects like playing cards and printed money. So printing is a technology that had an early impact on how people access and think about visual culture.

Elements of New Media Art: Democratizes access to art

In the chapter on Early Photography, we continue our historical exploration with a look at the impactful new technology of photography, invented in the nineteenth century. Like printing, photography is a powerful precedent to New Media Art because it democratized image making around the world and increased the amount of images that average people had access to in the twentieth century. In the 1850s, few people had access to a camera, but a short 100 years later, it would have been unusual to meet someone who didn’t own a camera. By the 1950s, photographic images had become the daily visual diet of people living in urban centers across the world. Photography is part of the lineage of New Media Art because it gave power to average people, allowing them to make their own images and tell their own stories. Additionally, photographic manipulation is as old as the development of photography, allowing artists to invent new realities, another strategy of New Media Art.

Elements of New Media Art: Merges old media with new media

In the chapter on Early Film and Animation we examine the earliest gifs and movies from the late nineteenth century and discusses their impacts on later developments in New Media Art. Just like photographers experimented with new technology, artists working in early film and early animation used strategies from traditional art media like painting to experiment with the technology of film. Some early film artists were also interested in thinking about what motion pictures could do that painting and photography could not, so they proposed new directions for image making in this infant medium.

Additionally, in the Early Video Art chapter we examine the impact of television and portable video cameras on artists, like Nam June Paik, who linked his interests in electronics, music, performance, chance, Buddhism, and Korean shamanism, to create innovative work merging the traditional art media of sculpture with the new media of video. In the chapter covering Digital Video Art we examine the shift to digital video and the merging of video sculpture with installation art in the new cavernous museum spaces of the postmodern era. In these chapters, we also draw a distinction between art that uses digital technologies as tools for creating more traditional art objects and digital-born art that is created, stored and distributed via digital technologies, using digital tools as a medium.

Elements of New Media Art: Variable

The artist Rafael Lozano-Hemmer (born 1967) employs digital technologies to create immersive installations that are dependent on viewer engagement and are therefore variable, meaning that the installations change as each new person engages with the work. In Pulse Index, first created in 2010 and reinstalled at the Hirschhorn Museum in Washington DC in 2019 as part of a larger exhibition of the artist’s Pulse series, Lozano-Hemmer collected the fingerprints and heartbeats of every person who visited the show. The biometric data of the last 10,000 users was then projected onto the curved walls of the Hirschhorn gallery in an ever growing grid that changed with the electrical pulses of each new human who entered the space.

Art and Technology in the Late Industrial Age

We can find the conceptual roots of New Media Art in early twentieth-century Europe, because artists in this time of turmoil invented entirely new artistic languages and techniques that form the foundation of New Media strategies and are still used by artists today. In the 1900s when the first motion pictures were made, there were many other radical shifts in technology. Inventions like the airplane, automobiles, skyscrapers, light bulbs, radios, phonographs, portable typewriters, electric elevators, telephones, and even aerial bombing, were all introduced for the first time. Historians have argued that any one of these new technologies would have caused a serious revolution in human behavior, but people experienced many of these new technologies all at once. And some artists began to look for ways to explore and express the strange, exciting, and terrifying world they saw unfolding around them. Artists began to seek new ways of representing space, time, and movement in order to open people’s eyes and ears to the beauty and horrors of the modern machine age.

One technique some artists used to reference the chaos of the machine age was simultaneity, often by showing multiple viewpoints in one painting as Georges Braque (1882-1963) and Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) explored in Cubism or multiple camera angles in one film sequence as visible in the experiments of Fernand Léger (1881-1951). Prior to the twentieth-century, life had seemed more static, but science and technology were forcing people to experience time, motion, and space more dynamically. Reality was in a constant state of flux in the early twentieth-century and some artists began to highlight the uncertainty and ambiguity that permeated their world.

This period, called the Machine Age by some, began more than 100 years after the first wave of the Industrial Revolution. By the 1920s, artists, designers and architects had finally developed a set of aesthetic forms and principles that spoke more dynamically and effectively to the new realities of the industrial world. So it took artists about 150 years to build new artistic languages out of the impacts of industrialism. And the world has only been living through the Digital Revolution for a few decades at this point. What kind of new languages are New Media artists currently inventing? What will they be proposing 100 years from now? What new aesthetic forms and principles will ultimately speak more effectively to the new realities of our global and digital world? What is the role of New Media Art in engaging with some of the most pressing concerns of the twenty-first century?

The Dada Precedent

Many historians link the history of New Media Art to the early twentieth-century, when the Dada movement emerged in Zurich, then Berlin, Cologne, Paris, and New York. Dada artists were highly critical of traditional institutions and the bourgeois culture that they felt led Europe into the First World War. They were horrified by the industrialization of warfare and became interested in engaging with the world of technology (including mechanically reproduced images and objects) in critical ways. They began to radically challenge traditional ideas about art and propose new ways of engaging with the modern world. As artist Mark Tribe has argued, New Media Art is similarly a response to the revolution of information technology. Dada artists critically engaged with the mechanization of cultural forms, and New Media artists critically engage with the digitization of cultural forms.

Lev Manovich has noted that many Dada strategies reappear in New Media Art. For example, Dada artists were among the first to use their body and time as artistic mediums leading to the development in New Media Art known as Performance Art. Another significant example is the Readymade, which involved the artist introducing objects from life into art by choosing something that has already been made and calling it art. The artist Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) coined the term Readymade to explain his process of taking something that was already made, particularly something mass produced by a machine and removing it from its usual context by inserting it into an art context. This approach emphasized the importance of context in how people interpret, understand, utilize and appreciate things in their daily lives. Many New Media artists also explore the importance of context and how one’s ideas and understandings can change depending on the position(s) from which one is experiencing something.

The most famous (or infamous) Readymade is a piece called Fountain. Today there is debate about whether or not Fountain is a work by Marcel Duchamp or Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven (1874-1927), but what we do know is that the piece was a machine-made urinal, dated and signed “R. Mutt” and submitted to an art exhibition in 1917. This work, while rejected from the exhibition by the jury, ended up demonstrating how the context of fine art can often impact the way we value and understand an object. A urinal is a plumbing fixture people pee in until an artist signs it and enters it into an art show, where it’s placed on a pedestal to be aesthetically appreciated. Fountain and the many other Readymades by Duchamp, suggest that the way art is identified and interpreted is not natural, but cultural. Some things are considered “art” and others considered “not art” based on cultural context and the word “art” itself has a variety of different meanings depending on the language and cultural context in which it is being used. For example many creative works were never made to be exhibited in a museum and don’t fit into the specific definition of art maintained by Euro-American art history. Readymades highlight this complexity and some New Media Artists use this strategy to further question traditional definitions of art. (Here is an explanation of R. Mutt’s Fountain written by Marcel Duchamp in 1917.)

Elements of New Media Art: The Glitch

Readymades opened the doors for New Media Art by posing questions that future generations of artists continue to explore. Does art have to be about technique or skill? Does art have to be about an individual artist and their expression? What if a work of art just makes the person engaging with it think or feel? Do works of art have to look certain ways or be made with certain techniques to contrast with “real things”? How do we know if something is art or not? Who gets to decide what is art and what isn’t? And why should we make this distinction at all? Humans have been making beautiful and complicated things for millennia with a variety of goals in mind. Readymades show that the aesthetic function of traditional European art has a very specific (and very recent) context.

The idea of “Fine Art” being a single object, made by one artist, that you look at in a museum and appreciate for its beauty with no other purpose, was invented in the 18th century, and solidified when the first public museums opened in Europe. It is this model that New Media Art challenges. And Dada artists paved the way for this new direction by shifting focus from the eye to the mind. Dada suggests that art doesn’t have to be about skill, materials or form. Instead art can be about process. Art can be about what is being said. And this shift from the art object to the idea or concept has had a major influence on New Media Art. (For another look at the development of art as an idea rather than an object, see this short history of Conceptual Art from the Tate Gallery.)

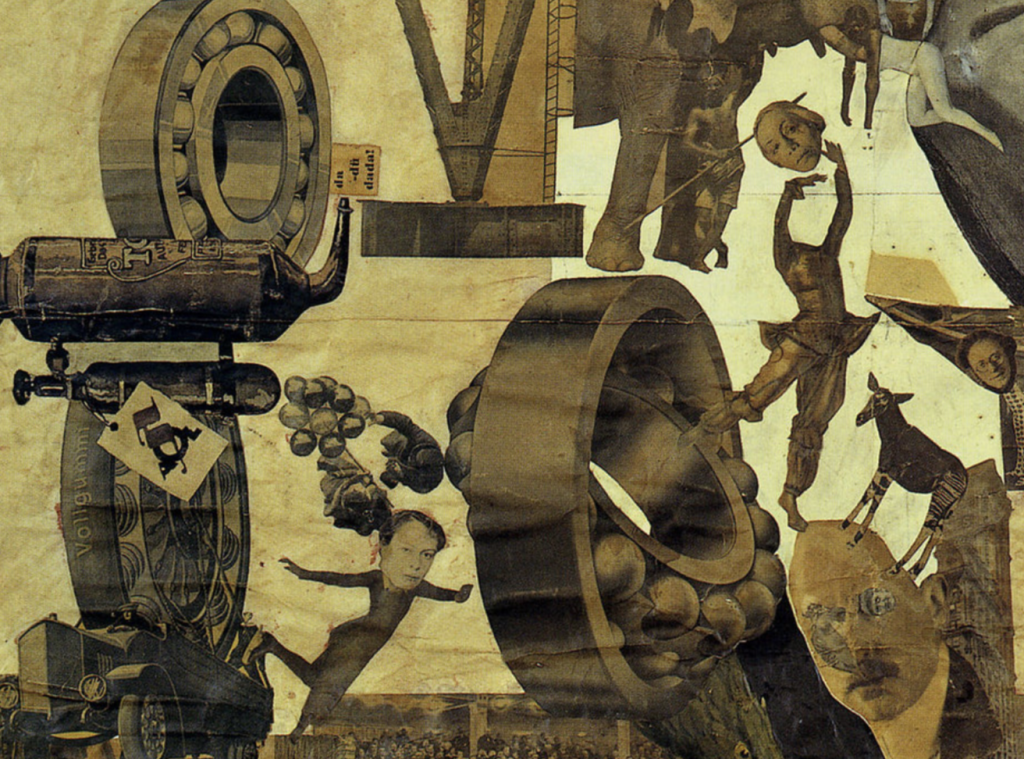

Elements of New Media Art: Remixing

Most art made in Europe in the early twentieth-century privileged evidence of the artist’s originality and mastery. However, Dada art, including Readymades, tried to show that art making doesn’t have to be about mastery. Dada proposed that creativity could be about remixing. Dada artists like Marcel Duchamp and Hannah Höch (1889-1978), often appropriated objects from mass culture or borrowed images from the mass media and manipulated them to create new meaning. Of course, artists have always influenced each other and imitated each other, but the concept of remixing (or appropriation) was truly born in the early twentieth-century when mechanical reproduction enabled new forms of copying and repurposing images made by others to communicate in new ways. In the 1920s, Höch repurposed images she cut from German women’s fashion magazines to expose the objectification and commodification of gender in the post-war era.

Dada photomontage was only one critical approach to popular culture in the twentieth-century. In the 1960s, Pop artists in the US and UK remixed popular advertising, pulp fiction and comics to explore the realities of capitalism, consumerism and celebrity in the mid-century. The Situationists International, also developed a concept called détournement, which involves appropriating familiar images from the mass media or ubiquitous political slogans, and using them in ways that subvert their original message and expose their embedded ideology. This strategy was used on graffiti and posters during the 1968 Paris uprising and it later influenced Punk and Riot Grrrl design and groups like the Billboard Liberation Front, which used images from the spectacle to disrupt its seamless flow.

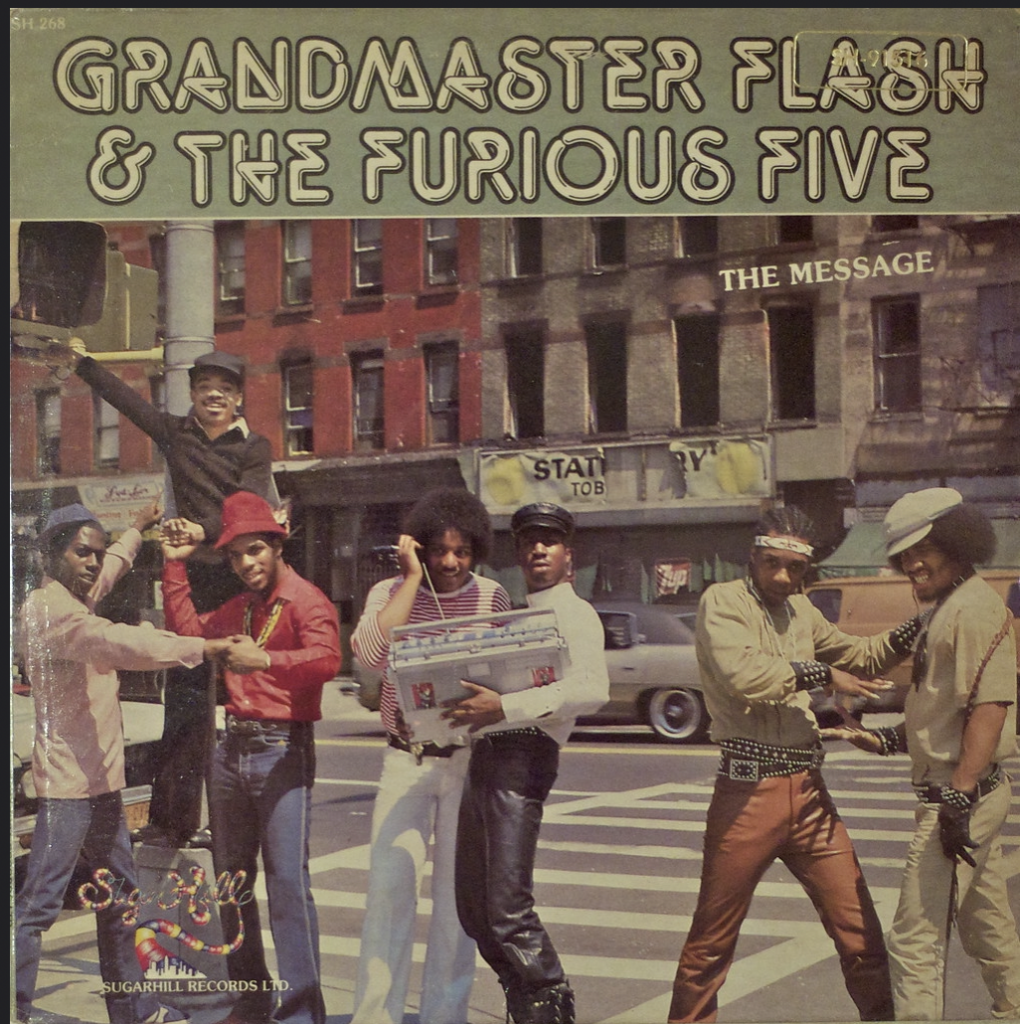

Perhaps most closely connected to the intermedia elements of New Media Art, Hip Hop DJs in the 1970s and 1980s started sampling beats, phrases and lines of music from older records, remixing works of art by earlier artists into new dynamic work that existed in dialogue with the poems written by MCs, the movements created by B-Boys and B-Girls and the painted images and words created by graffiti artists. The debut album The Message by hip hop giants Grandmaster Flash (born 1958) and the Furious Five provides an early, though certainly not the first, example of hip hop remixing. Songs on the album include samples of funk beats by the Jimmy Castor Band, fragments of disco songs by Chic and new wave riffs by the Tom Tom Club. The first single from the album, also titled “The Message” provides an early example of critical social commentary that has remained a significant element of hip hop music, continued by later groups like Public Enemy, KRS-One and Black Star. Hip Hop sampling and remixing has had a major influence on New Media artists today and provides an early example of the elements of New Media Art permeating all aspects of life.

The development of the World Wide Web in the 1990s provided artists with even easier access to found images, found sounds and found texts, and many artists became interested in engaging with this new abundant source material that was always growing as new sources were constantly being added. Digital technologies made it much easier to copy and paste so by the 1990s, borrowing and remixing had become a significant creative act. Of course, at the same time that remixing became an increasingly important artistic strategy, intellectual property laws were also becoming more restrictive. The recording industry, movie studios and other corporate content owners were increasingly concerned about unauthorized copying and distribution of their assets. Copyright terms were extended and violations were aggressively policed. This book explores the ways that some New Media artists and New Media theorists have responded and continue to embrace remixing in the twenty-first century as our digital environment continues to evolve.

One powerful example of a recent work of remixing informed by both the joyous sampling of hip hop and the critical appropriation of Dada is Arthur Jafa’s (born 1960) Love is the Message, The Message is Death. (Content warning: police violence) This is a video epic that appropriates archival film, videos with “Getty images” watermarks, and grainy smart phone videos posted online to tell a complicated story of contemporary visual culture. Writer and Rhizome editor Aria Dean, has situated this work within the Black Radical Tradition, as a video that explores the way American culture views Blackness and Black people, and exposes how those views are deeply informed by white supremacist visual culture. Jafa’s video also alternates images of Black excellence and joy with violence and suffering, which Dean has connected with the call and response structure of Black church gatherings. Jafa’s remixing also brings moments together that have never been juxtaposed before, to propose new ways of thinking critically about the visual world we carry around in our pockets.

Elements of New Media Art: Chance

Dada artists, along with the later Surrealists, also used chance as an art making strategy to jar audiences out of their complacency and encourage them to see the world around them with new eyes. Some artists saw chance as a way of rejecting the focus on the individual, genius artist. Chance shows up through audience involvement in early Dada performance work, where the artists could not control the outcome. Additionally, Dada poets developed rules for their process of creation and scholars like Lev Manovich have connected those rules to algorithms that form the basis of all software and computer operations. In his article “Avant-Garde as Software” Manovich proposes that the 1920s avant-garde is one of the most significant predecessors to contemporary New Media Art. Because avant-garde artists and designers in the early twentieth-century invented an entirely new set of visual and spatial languages and communication techniques that we still use today. These techniques became embedded in the commands and interface metaphors of computer software according to Manovich.

Dada artists (and the Italian Futurists) were also interested in opening people’s ears to the noises and sounds of everyday life in the Machine Age. They can therefore be considered precursors to later experimental musicians like John Cage (1912-1992), whose approach to art making is deeply engaged with New Media strategies. Cage was very interested in opening people’s ears to the sounds of the world around them. Additionally, Cage employed algorithmic precedents and chance to compose his music, including basing instructions for musical compositions on the I-ching. Cage had a major influence on Fluxus and Neo-Dada artists and his own compositions from the 1950s and 60s anticipated numerous experiments in interactive New Media Art.

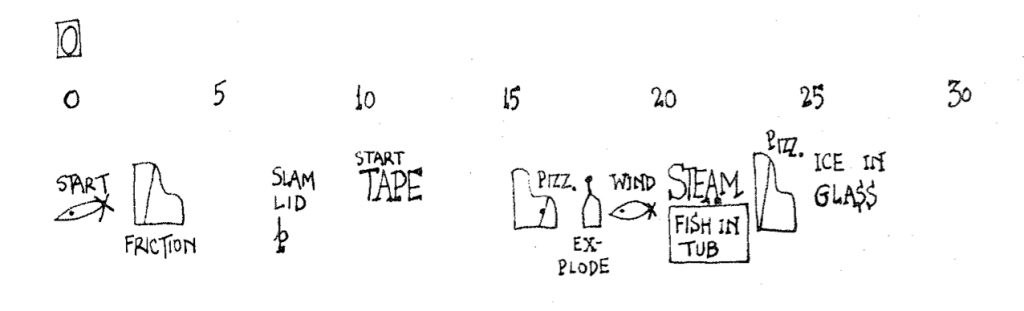

Cage’s work proposes that the distinction traditional art history tries to draw between art and the rest of the world is in fact, a false distinction. Cage and the artists he inspired attempted to embrace the art in daily life. Cage even famously explained that “There is no such thing as silence. Something is always happening that makes a sound.” His 1959 composition, Water Walk, provides a good example of this approach with sounds made by “instruments” drawn from a variety of items related to water and found in most homes.

Elements of New Media Art: Interactive

The Fluxus and Neo-Dada Precedent

In this book, we also consider approaches that engage the Elements of New Media Art and were influenced by Dada, John Cage, and the groups he influenced, including the development of Social Practice Art. Social Practice Art fully engages the New Media strategy of active viewer participation by trying to erase the notion of a viewer and proposing that everyone can be a creator. As you’ll read in the chapter on Social Practice Art, it’s a development that was influenced by artists like the Fluxus artists working internationally after WWII. Many artists started to feel that their social bonds were becoming fragmented in the modern world and they wanted to challenge this fragmentation by providing open-ended alternatives to people’s disconnected lives.

Some artists began to think that the best way to revitalize culture and forge stronger social bonds was to creatively integrate art into everyday life. These artists in the 1960s and 1970s tried to challenge traditional relationships between the viewer, the artist and the art work by inventing new ways of making and experiencing art. Many of these artists argued that art could encompass actions and ideas as well as objects, influenced by Dada. For example, the group that called itself Fluxus, designed open-ended events based on the creative execution of instructions or event scores. Fluxus event scores blur the boundaries between art and life and between the viewer and the artist. They can be realized in a variety of ways and by anyone. They require full engagement and presence in order to be made real.

Elements of New Media Art: Collaborative

Fluxus events and other experimental developments in the 1960s initiated a shift from passive audience reception to active participation, that earlier twentieth-century artists proposed. Traditional art mediums result in works of art that are objects viewers gaze at, but New Media Art is more interactive. In fact, one of the hallmarks of New Media Art is participation, viewer engagement and sometimes even creation. This is in part because the Digital Revolution has fundamentally reshaped the way cultures are created, experienced and understood. New Media Art also provides the public more opportunities to be active producers of art or participants in the production, instead of passive observers.

However, there are different levels of interactivity and some New Media Art projects allow viewers to themselves become artists, leaving traces on the work or dramatically altering it, whereas other New Media Art projects respond to audience input, but are not altered by that input. In both cases, the presence of the viewer is vital. Without the viewer, many New Media Art projects would not be activated. Yet some projects provide space for more intense interaction than others.

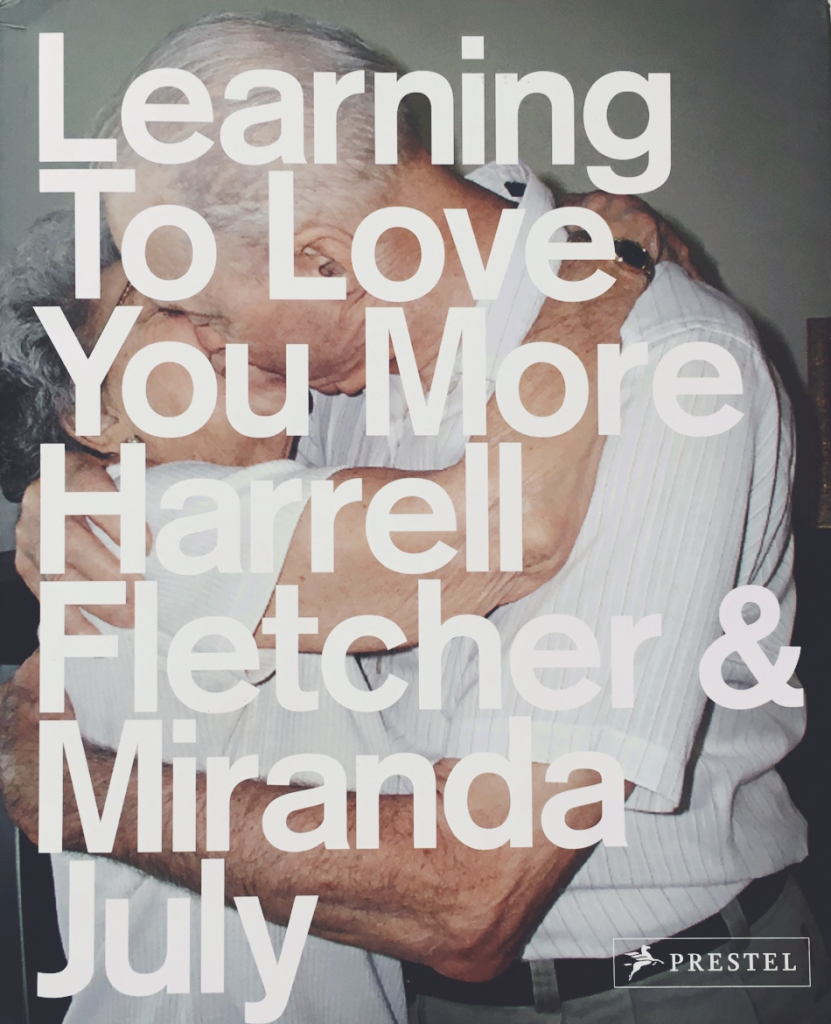

One example is the collaborative project initiated by Miranda July (born 1974) and Harrell Fletcher (born 1967), titled Learning to Love You More. Starting in 2002, July and Fletcher began sharing assignments online. Anyone who wanted could complete the assignment instructions and submit documentation of their work to be posted on their website. Assignments like “Make a Neighborhood Field Recording” and “Take a Picture of Your Parents Kissing” were completed by thousands of participants and shared online as well as eventually in museum exhibitions and a published book. These assignments recall Fluxus event scores and provided a recipe or framework within which anyone could meaningfully explore aspects of what it means to be human and to meaningfully relate to other humans in the digital age.

The Feminist Art Precedent

For a generation of artists in the 1950s and 1960s who had witnessed the destruction of the Holocaust and the atomic bomb, the body and specifically their own body, offered a powerful medium to communicate shared physical and emotional experiences. In the politicized environment of the 1960s, many artists used performance art specifically to address emerging social concerns. And in this period, feminist artists became major innovators. Feminist artists in the 1970s, began to use their own bodies in live performances, realizing that it was an effective way to expose the context of art history and challenge historical representations of women. Additionally, unlike traditional art forms such as painting and sculpture, performance art forced viewers to engage with a real person and their real emotional and physical states. The critical challenges lodged by feminist artists against the status quo of the art world, the argument that the personal can be political and the embrace of creative forms of making that had been marginalized in Western art history, all provided a framework for thinking about how New Media Art could challenge traditional narratives and oppressive structures.

Elements of New Media Art: Connectivity

The Industrial Age becomes the Information Age

The formative years of New Media Art followed the end of the Cold War, when many artists were critical of capitalism and the victory of free-market ideology symbolized by the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Many left-leaning artists saw the Internet as an opportunity to realize progressive, anti-capitalist ideals, including embracing a “gift economy” with works of New Media Art circulated for free or exchanged via websites and listservs. Artists leaned into the roles of mediators or facilitators rather than sole creator. Works of art began to engage viewers in new ways. They began to rely on a constant flow of information and many became open structures in the process. Digital technologies even further challenged traditional notions of the what an artist, audience member and work of art even is.

How is New Media Art different from Traditional Art?

New Media Art reflects dramatic changes in traditional ideas about how and why art should be made. New Media Art is often made by artists who aspire to question traditional notions of what art is, what art can be about, who makes art and why. As we will see in this book, these are questions that many artists were beginning to ask long before the Digital Age. As early as the nineteenth century, artists were beginning to contradict what had previously passed for art and to make work that challenged people’s expectations about what they should be able to see in an art gallery or exhibition space. For example in nineteenth century France, people rejected Gustave Courbet’s (1819-1877) The Stonebreakers, because it looked different than traditional Academic painting and it introduced an image of hard, back breaking labor to an art audience that wanted to escape and to be entertained when they looked at art. French viewers had a similar reaction to French Impressionism in the 1870s, deeming it not art because the painting style didn’t look finished enough compared to the so-called “licked finish” of Academic paintings.

According to the musician Brain Eno (born 1948), “Nearly all of the history of art history is about trying to identify the source value in cultural objects. Color theories, and dimension theories, golden means, all of those sort of ideas, assume that some objects are intrinsically more beautiful and meaningful than others. New cultural thinking [or New Media thinking] isn’t like that. It says that we confer value on things. We create the value in things. It’s the act of conferring that makes things valuable.”

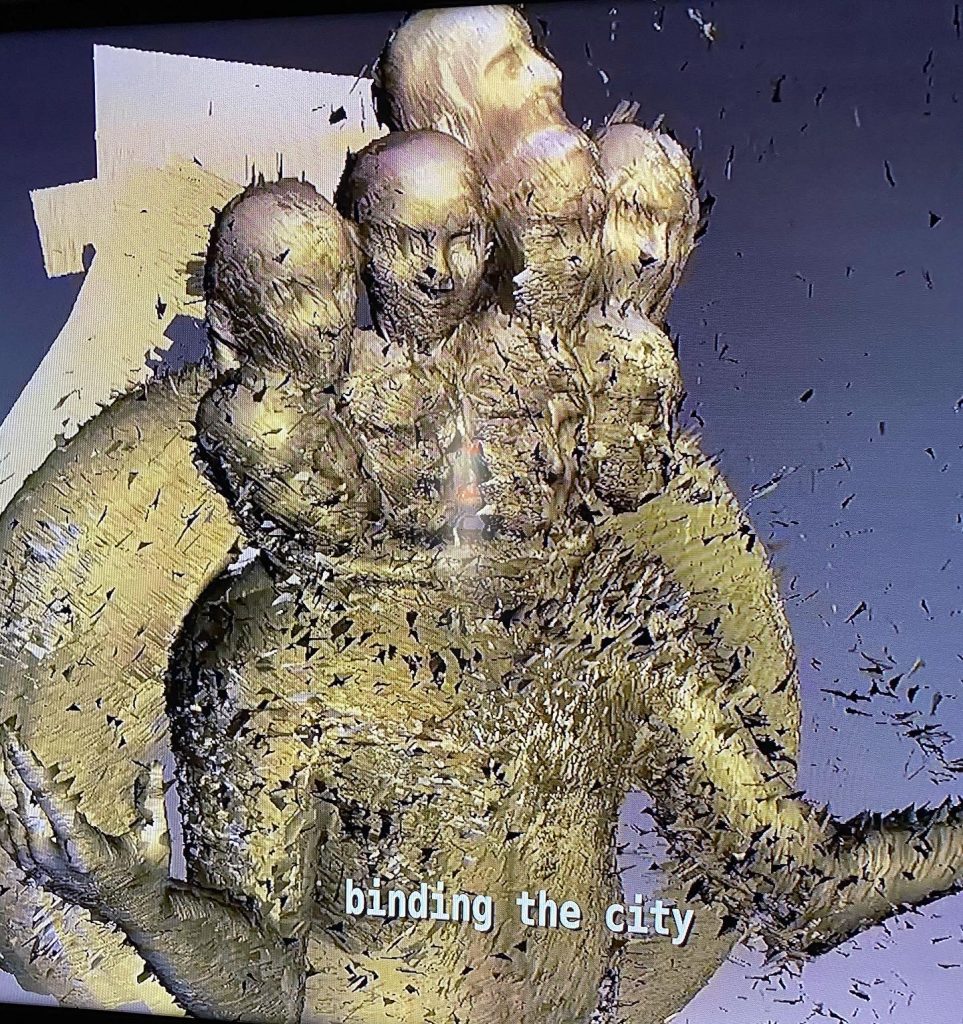

New Media artist Morehshin Allahyari (born 1985) uses digital tools to raise questions about how the value conferred on cultural artifacts and narratives is informed by historical power imbalances and the colonizing framework of art history. In She Who Sees the Unknown, Allahyari uses 3-D modeling to re-figure female goddesses and Jinn figures from Persian and Arabic narratives that have often been misrepresented and under-valued in Western culture. Allahyari’s work thus examines the past and explodes gender, cultural and social norms through the medium of emerging technologies.

Artists have been challenging expectations and expanding the boundaries of art for centuries. In this book, you will encounter work by many New Media artists who have made things or proposed things that would not have been defined as art in the past. Many New Media artists deliberately challenge viewers’ expectations about what a work of art should look like and how a work of art can function. However, all of the works introduced in this textbook have redefined the concept of art in powerful ways, and the best way of engaging with this book is to approach each work of art with curiosity, by asking questions and trying discover meanings. The goal is not to find one answer, but to participate in a dialogue, to examine how each work of art is situated within the broader framework of New Media Art and to consider what each work of art contributes to the global human dialogue that we all participate in thanks to the Digital Revolution.

New Media and 4-D Art

Before the twentieth-century, art history used to focus on two-dimensional and three-dimensional art. Two-dimensional art like painting and drawing has a flat surface, with shapes that are given an illusion of mass and an illusion of space and movement by an artist using value, line and color. (See the Visual Analysis chapter for more information on the visual elements and principles of design as they relate to New Media Art too.) Three-dimensional art like sculpture has actual mass, not an illusion of mass. It also employs space as a design element.

Before the twentieth-century, 2-D and 3-D art were the only two categories of art that were collected, exhibited and considered Fine Art in Europe. Many forms of New Media Art, including film and video art are instead four-dimensional, or Time-Based Art. These works of art go beyond the flat surface of two-dimensional art and they go beyond the static nature of most three-dimensional art. Four-dimensional art incorporates actual motion and actual elapsed time as part of its design. (Check out this description of 4-D Art from Medium and look at the 4-D Design Program at Cranbrook for more ideas about how 4-D art is defined today.)

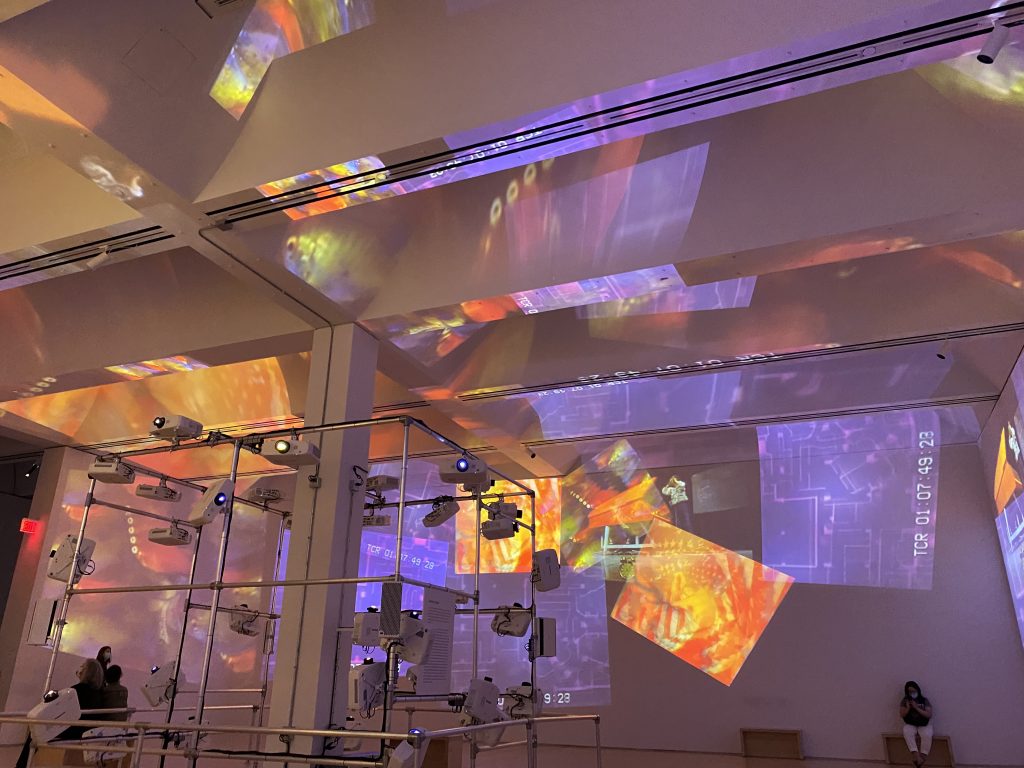

For example, the artist Nam June Paik paid homage to an iconic work of 2-D art by the Italian Renaissance artist Michelangelo (1475-1564), by creating a new 4-D Sistine Chapel. Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling is a series of static paintings featuring stories from the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. Michelangelo painted these stories on the ceiling of a chapel in Vatican City at the request of the Pope. You have to travel to Rome to see these paintings, and you are meant to view them in reverent silence. In 1993, Paik created a new Sistine Chapel for the Digital Age. His chapel can be reinstalled in many locations. It was first shown at the Venice Biennale and most recently has been on view in San Francisco at the Museum of Modern Art. It consists of multiple video screens playing loops of videos made by Paik himself and mixed with appropriated videos from commercial television. The installation juxtaposes moments of silence and calm, with rapidly moving images and loud sounds, creating an immersive experience that perhaps seemed strange and new in the early 1990s, but today feels as if the installation honors or exposes most people’s day-to-day experience with visual culture.

When considering the differences between traditional art media and New Media Art, consider why some artists began to shift away from traditional modes of expression and how the Digital Revolution created new ways of valuing, evaluating and engaging with art. How can we understand projects that employ emerging technologies but don’t engage with the Elements of New Media Art? What are some of the differences between Nam June Paik’s 1990s Sistine Chapel video installation and the commercial digital recreation of Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel that toured the US in 2022? Does the traveling Sistine Chapel exhibition engage with the Elements of New Media Art or is it more related to elements of Traditional Art Media?

Differences between Traditional Media and New Media in Art:

| TRADITIONAL ART MEDIA | NEW MEDIA ART |

| A one of a kind object. | Work in multiple states or copies. |

| Made by a single artist. | Collaborative authorship with other artists and/or the viewer. |

| Geographically limited. | Can be accessed anywhere. |

| Work has an end or is finite. | Work is in a state of flux; the viewer can change or “complete” the work. |

| One way communication; the viewer is passive. | Two way communication; the viewer is an active participant in the work’s creation and completion. |

| Art is something you look at. | Art is something you interact with. |

| The artist has control over what the viewer sees. | The artist has limited control. |

| The content and presentation cannot be separated. | The content and presentation can be separated; the viewer provides the medium. |

| Artwork is distributed by galleries and official institutions, like museums. | Artwork bypasses gallery and museum systems. |

Look & Consider: Traditional Art Media

To explore the differences between Traditional and New Art Media let’s consider another famous Italian Renaissance painting, the Mona Lisa. The painting was completed between 1503 and 1519 by the artist, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519). To the left is a digital image of the original oil on wood panel painting. If you’ve never seen the Mona Lisa before, you can read more about its history in this detailed Wikipedia entry.

Review the table above and consider which qualities of Traditional Art Media you think apply to Leonardo’s painting and why.

Explain how the painting is geographically limited, a one of a kind object, one way communication, something you look at.

What other elements of “Traditional Art Media” resonate as you examine this painting?

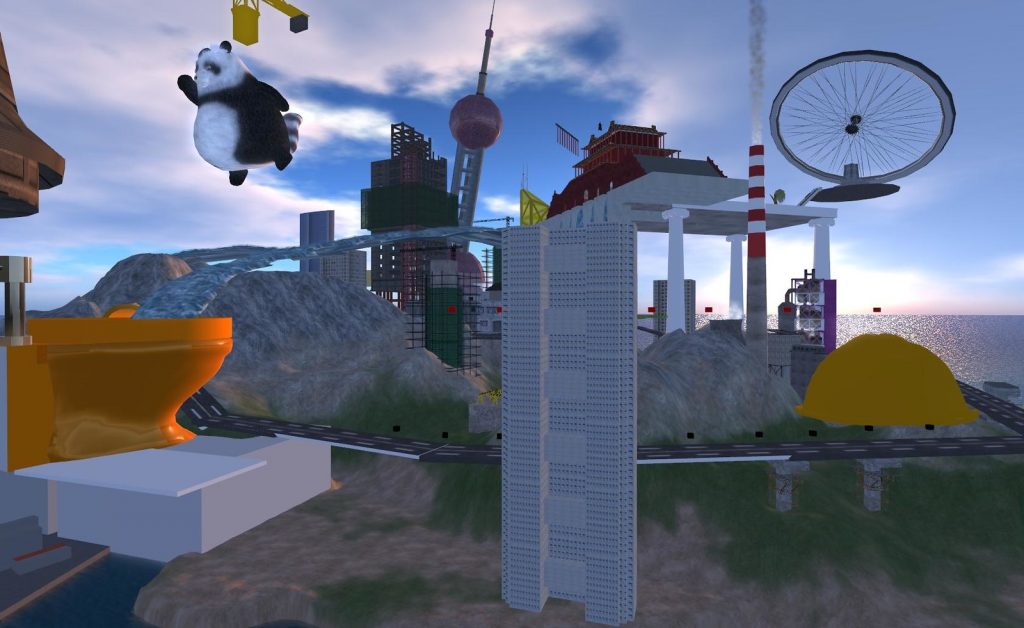

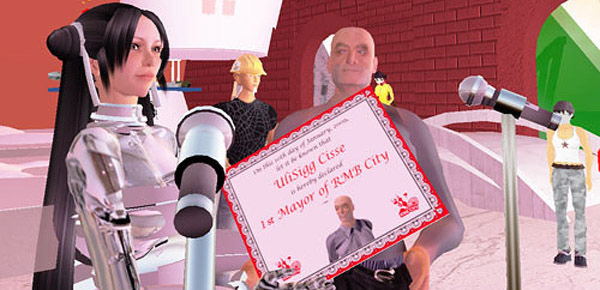

Watch & Consider: Cao Fei

You’ve considered the Mona Lisa as a good example of Traditional Art Media. Now watch this interview with the artist Cao Fei on Art:21 (13:43 minutes). Cao Fei’s (born 1978) work is another good example of New Media Art so consider some of the ways her work relates to the qualities of New Media in the table above while listening to this interview.

Take notes in response to the following questions after watching the video:

- What makes Cao Fei’s work a good example of New Media Art? (Which of the Elements of New Media Art does her work engage with?)

- What are some examples of role-playing and avatar creation in Cao Fei’s work? What kinds of characters and avatars does she create and allow viewers to create? Why do you think this approach is of interest to Cao Fei?

- Why does Cao Fei support the ability to fantasize in her art? In what ways can imagination contribute to building new worlds? How might fantasy be a strategy to cope with something that is overwhelming or seems beyond one’s reach?

- Cao Fei says that she thinks it is common in the nature of human beings to dream of establishing one’s own rules of the game. How does Cao Fei’s work in Second Life or in her videos provide a platform to experiment with dreaming and imagining new futures?

- What are some major differences between Cao Fei’s work and more traditional art media like painting or sculpture?

Comparison: Traditional Media + New Media

Questions to Consider:

- What are some of the most significant differences between the Mona Lisa by Leonardo da Vinci and RMB City by Cao Fei?

- Why is Cao Fei’s RMB City NOT geographically limited?

- Why is RMB City NOT a one of a kind object?

- Why is RMB City NOT one way communication?

- What are some of the major differences between the ways these two works of art engage the audience?

- What kind of meanings are generated by both works of art? What are some differences in the meanings you can draw from each one?

- Are there other differences that mark the Mona Lisa as traditional art media and mark RMB City as New Media Art? If so, explain what you’re seeing.

Conclusion

We will continue to consider the various ways that New Media Art both differs from and is building on traditional art media throughout the rest of this textbook. As you explore the other chapters in this resource, you’ll also have many opportunities to consider how the works of art you’re examining relate to the proposed Elements of New Media Art and other concepts presented in this chapter. Remember that this entire textbook is a preliminary and exploratory look at a field that is constantly evolving, so your engagement with New Media Art while using this textbook is only a starting point. Our ideas about and understanding of this field will continue to grow as we move through the rest of our lives encountering experiences proposed by artists who work in New Media.

Key Takeaways

By working through this chapter, you will begin to:

- Identify the central issues we’ll explore throughout this textbook.

- Explain why the study of New Media Art is important today.

- Recognize that there are many different definitions of words like “art” and “artist” and that those varying definitions are representative of particular historical moments and cultures by considering the differences between New Media in art and Traditional Art Media.

- Identify and explain some of the many elements, definitions and categories of New Media Art.

Selected Bibliography

Acland, Charles R., ed. Residual Media. University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Bell, Adam and Charles Traub, eds. Vison Anew: The Lens and Screen Arts. University of California Press, 2015.

Bishop, Claire. Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London and Brooklyn: Verso, 2012.

Bishop, Claire, ed. Participation (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Bolter, Jay Davide and Richard Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

Cornell, Lauren. Mass Effect: Art and the Internet in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2015.

Cook, Sarah. Information (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2016.

Goldberg, RoseLee. Performance Art: From Futurism to the Present. Thames and Hudson, 2011.

Grau, Oliver. Ed. Media Art Histories. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2007.

Greene, Rachel. Internet Art. Thames and Hudson, 2004.

Gronlund, Melissa. Contemporary Art and Digital Culture. Routledge, 2016.

Grosenick, Uta, Reena Jana and Mark Tribe. New Media Art. Taschen, 2006.

Hansen, Mark B.N., New Philosophy for New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2006.

Harvey, David. “The Fetish of Technology: Causes and Consequences.” Macalaster International. Summer 2003.

Kester, Grant. The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaboration in a Global Context. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2012.

Kholeif, Omar. Moving Image (Whitechapel: Documents of Contemporary Art). Cambridge, MA, MIT Press, 2015.

Manovich, Lev. “Avant-garde as Software“. 1999.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002.

Manovich, Lev. “The Practice of Everyday (Media) Life.” March 10, 2008.

Marx, Leo. “Technology: The Emergence of a Hazardous Concept”. Social Research. The Johns Hopkins University Press. Vol. 64, No. 3, Technology and the rest of culture. (Fall 1997): 965-988.

Montfort, Nick and Noah Wardrip-Fruin, eds. The New Media Reader. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2003.

Morris, Susan. Museums and New Media Art. A research report commissioned by The Rockefeller Foundation. October 2001.

Moss, Ceci. Expanded Internet Art: Twenty-First Century Artistic Practice and the Informational Milieu. (International Texts in Critical Media Aesthetics). Bloomsbury Academic, 2019.

Paul, Christiane. Digital Art. 3rd edition. Thames and Hudson, 2015.

Paul, Christiane. New Media in the White Cube and Beyond: Curatorial Models for Digital Art. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2008.

Quaranta, Domenico. Beyond New Media Art. LINK editions, 2013.

Reisser, Martin and Andrea Zaap. New Screen Media: Cinema / Art / Narrative. British Film Institute, 2002.

Respini, Eva. Art in the Age of the Internet: 1989 to Today. Yale University Press, 2018.

Ryan, Susan Elizabeth, “What’s So New about New Media Art?” Intelligent Agent, 2003.

Rush, Michael. New Media in Art. Thames and Hudson, 2005.

Russell, Legacy. Glitch Feminism. Verso, 2020.

Shanken, Edward. Art and Electronic Media. Phaidon Press. 2009.

Shirkey, Clay. Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing without Organizations. New York: Penguin. 2008.