4.9 Substantive Law: Punishment: Incarceration and Confinement Sanctions

Substantive criminal law not only tells us what actions are considered crimes but also sets the rules for how people who commit crimes should be punished. All parts of the government—like the executive branch, the judicial branch, and the legislative branch—play a role in deciding these punishments. When someone is found guilty of a crime, one of the most important jobs of a judge is to decide what punishment they should get. This is called imposing a sentence.

It used to be that judges had a lot of say in deciding how long someone would be punished, but nowadays, many places have mandatory sentencing, which means that judges have less freedom in making these decisions, and it’s more up to the prosecutors. So, deciding punishments is a team effort involving judges, prosecutors, and lawmakers. Over the past 30 years, people have also had a say in this through things like voting on propositions, referendums, and initiatives, which have a big impact on the kinds of punishments that are decided for different crimes.

Incarceration/Confinement Sentence

Confinement sanctions include incarceration in prisons and jails, incarceration in boot camps, house arrest, civil commitment for violent sexual offenders, short-term shock incarceration, electronic monitoring, etc. Most believe that confinement is the only effective way to deal with violent offenders. Although people question the efficacy of prison, incarceration somewhat protects society outside the prison from dangerous offenders. Prison is effective at incapacitation but rarely is it effective at rehabilitation. In fact, serving time in prison often reinforces criminal tendencies.

State and federal approaches to incarcerating individuals have shifted in response to prevailing criminal justice thinking and philosophy. Over time, governments have embraced four different approaches to sentencing offenders to incarceration: indeterminate, indefinite, determinate, or definite. Criminal codes may incorporate more than one single approach. These approaches can be seen as a spectrum of judicial discretion. Indefinite and indeterminate sentences, at one end, are those that allow judges and parole boards the most discretion and authority. Determinate and definite sentences, at the other end, allow little or no discretion. Currently, most states are following determinate sentencing coupled with sentencing guidelines, mandatory minimums, habitual offender statutes, and penalty enhancement statutes.

Indeterminate-Indefinite Sentencing Approach

For much of the twentieth century, statutes commonly allowed judges to sentence criminals to imprisonment for indeterminate periods. Under this indeterminate sentencing approach, judges sentenced the offender to prison for no specific time frame and the offenders’ release was contingent upon getting paroled, or rehabilitated. Because some criminals would quickly be reformed but other criminals would be resistant to change, indeterminate sentencing’s open-ended time frame was deemed optimal for allowing treatment and reform to take its course. The decline of popular support for rehabilitation has led most jurisdictions to abandon the concept of indeterminate sentencing. Indefinite sentences give judges discretion, within defined limits, to set a minimum and maximum sentence length. The judge imposes a range of years to be served, and a parole board decides when the offender will ultimately be released.

Determinate-Definite Sentencing Approach

Under determinate sentencing, judges have little discretion in sentencing. The legislature sets specific parameters for the sentence, and the judge sets a fixed term of years within that time frame. The sentencing laws allow the court to increase the term if it finds aggravating factors, factors indicating the offender or offense is worse than other similar crimes, and reduce the term if it finds mitigating factors, factors indicating the offender or offense is less serious than other similar crimes. With determinate sentencing, the defendant knows immediately when he or she will be released. In determinate sentencing, offenders may receive credit for time served while in pretrial detention and “good time” credits. The discretion that judges are allowed in initially setting the fixed term is what distinguishes determinate sentencing from definite sentencing.

Definite sentencing completely eliminates judicial discretion and ensures that offenders who commit the same crimes are punished equally. The definite sentence is set by the legislature with no leeway for judges or corrections officials to individualize punishment. Currently, no jurisdiction embraces this inflexible approach that prohibits any consideration of aggravating and mitigating factors in sentencing. Although mandatory minimum sentencing embraces some aspects of definite sentencing, judges may still impose longer than the minimum sentence and therefore retain some limited discretion.

Presumptive Sentencing Guidelines

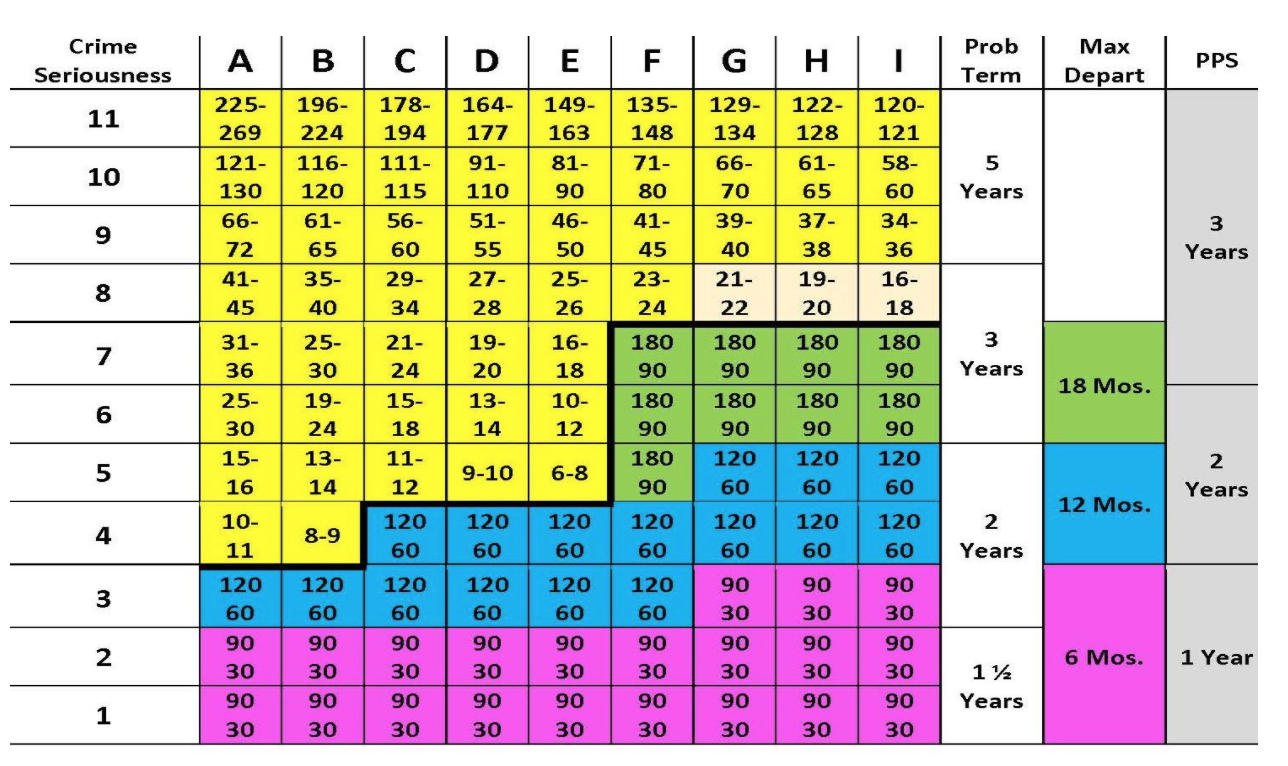

In the 1980s, state legislatures and Congress, responding to criticism that wide judicial discretion resulted in greater sentence disparities, adopted sentencing guidelines drafted by legislatively established commissions. Guideline sentencing allows for judicial discretion, but at the same time, limits that discretion. In figure 4.1 above, you can see just how detailed and complex these sentencing guidelines are in Oregon. Judges must generally make findings when sentencing the offender to a term of incarceration that is different from the presumptive sentence. The judge must indicate which aggravating factors or mitigating factors informed the departure. The Sentencing Reform Act of 1984 [Website] first established federal sentencing guidelines. The Act applied to all crimes committed after November 1, 1987, and its purpose was “to establish sentencing policies and practices for the federal criminal justice system that will assure the ends of justice by promulgating detailed guidelines prescribing the appropriate sentences for offenders convicted of federal crimes” (Scheb & Scheb, 2012). It created the United States Sentencing Guideline Commission and gave it the authority to create guidelines.

The Commission dramatically reduced the discretion of federal judges by establishing a narrow sentencing range and required that judges who departed from the ranges state in writing their reasons. The Act also established an appellate review of federal sentences and abolished the U.S. Parole Commission. Most states have adopted some version of sentencing guidelines, from the very simple to the very complex, and many states restrict their guidelines to felonies. Although limiting judicial discretion, state sentencing guideline schemes allow some wiggle room if the judge finds that the case differs from a typical case.

Other Mandatory Sentences-Penalty Enhancements

Legislatures have also exercised their authority over sentencing by passing laws that enhance criminal penalties for crimes against certain victims, for crimes committed with weapons, or for hate crimes. For example, Congress passed the Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act of 1994, which included several provisions for enhanced penalties for drug trafficking in prisons and drug-free zones. States have passed gun enhancements and hate crime enhancements. For example, Oregon’s ORS 161.610 [Website] authorizes enhanced penalties for the use of a firearm during the commission of a felony.

Concurrent and Consecutive Sentences

Frequently, judges sentence defendants for multiple crimes and multiple cases at the same sentencing hearing. Judges have the option of running terms of incarceration either concurrently (at the same time) or consecutively (back-to-back). States vary as to whether the default approach on multiple sentences is consecutive sentences or concurrent sentences.

Licenses and Attributions for Substantive Law: Punishment: Incarceration and Confinement Sanctions

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Substantive Law: Punishment: Incarceration and Confinement Sanctions” is adapted from “3.8. Substantive Law: Punishment: Incarceration and Confinement Sanctions” by Lore Rutz-Burri in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modifications by Sam Arungwa, revisions by Roxie Supplee, licensed CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 include revising for clarity.

A system of rules enforced through social institutions to govern behavior.

A penalty imposed on someone who has committed a crime.

A facility that houses people convicted of serious crimes and sentenced to long terms of incarceration.

Removing an individual from society for a set period to prevent them from committing crimes.

The process of helping someone who has committed a crime change their behavior and become a productive member of society.

The release of a prisoner under supervision after serving a portion of their sentence.

Factors that make a crime more serious and warrant a harsher punishment.

Circumstances that lessen the seriousness of a crime and may lead to a lighter sentence.

The authority of a court to hear and decide a case.

The criminal justice system is a major social institution that is tasked with controlling crime in various ways. It includes police, courts, and the correction system.