5.6 Other Modern Criminological Theories

Apart from classicalism and positivism, the following theories represent most of the modern criminological theories used by criminologists today.

Strain Theory

Strain theories suggest that people may turn to crime when they face stress or pressure in life. Emile Durkheim thought that inequality and crime weren’t directly linked unless society’s norms broke down due to rapid change. Robert K. Merton believed in the American Dream but saw that not everyone had equal opportunities to achieve it. When people face barriers to their goals, they might adapt in different ways: by conforming, innovating, ritualizing, retreating, or rebelling.

Merton focused on economic strains, but Albert Cohen thought status was also important, especially for teens in lower-class families. Cohen found that some teens turned to crime to gain status among peers. Robert Agnew later expanded on strain theory, saying that strains can come from many sources and lead to negative emotions like anger and depression, which can push people towards crime as a way to cope.

In simpler terms, strain theories suggest that when people feel pressure or face obstacles, they may resort to crime as a way to deal with their problems.

Learning Theories

In the previous section, strain theories focused on social structural conditions that contribute to people experiencing strain, stress, or pressure. Strain theories explain how people can respond to these structures. Learning theories complement strain theories because they focus on the content and process of learning.

Early philosophers believed human beings learned through association. This means that humans are a blank slate, and our experiences build upon each other. It is through experiences that we recognize patterns and linked phenomena. For example, ancient humans used the stars and moon to navigate. People recognized consistent patterns in the stars that enabled long-distance travel over land and sea.

Classical Conditioning

A few centuries later, Ivan Pavlov was studying the digestive system of dogs. His assistants fed the dogs their meals. Pavlov noticed that even before the dogs saw food, they began to salivate when they heard the assistants’ footsteps. The dogs associated the oncoming footsteps with the upcoming food. This type of learning is called classical conditioning, as noted in figure 5.7.

The acquisition of this learned response occurred over time. Human beings most certainly learn via classical conditioning, but it is a passive and straightforward approach to learning. You may feel fearful when you see flashing blue lights in your rearview mirror, salivate when food is cooking in the kitchen, or dance when you hear your favorite song. You passively learn from these events paired with your experiences.

Operant Conditioning

B.F. Skinner (1937) was also interested in learning, and his theory of operant conditioning transformed modern psychology. Operant conditioning is a form of active learning where organisms learn to behave based on reinforcements and punishments. Using rats and pigeons, Skinner wanted animals to learn a simple task through reinforcement. A reinforcement is any event that strengthens or maximizes a behavior that should continue or increase. Positive reinforcement is the addition of something desirable, and negative reinforcement is the removal of something unpleasant. For example, if you wanted more people to wear seatbelts, you would want to reinforce the behavior. A positive reinforcement is praise or a reward for buckling up. A negative reinforcement is the seat belt alarm that comes in newer cars. It rings until you buckle up, and once you do, the ringing stops. Both examples reinforce the behavior but in different ways.

Punishments are given to discourage or reduce a behavior. A positive punishment gives something unpleasant, and a negative punishment takes something away. For example, parents who want their teenager to stop breaking curfew can punish the teen in two ways. A positive punishment is scolding. A negative punishment is taking away the teen’s driving privileges. Both punishments aim to stop the breaking of curfew, but in different ways.

Optional Activity: Punishment Exercise

How does the Criminal Justice System positively punish offenders? How does the Criminal Justice System negatively punish? Give examples of both.

Differential Association Theory

In 1947, sociologist Edwin Sutherland introduced the differential association theory to explain how people learn criminal behavior. Here are the key points:

- Criminal behavior is learned through communication with others.

- Learning criminal behavior mainly happens within close personal groups.

- When learning criminal behavior, people also learn techniques and attitudes related to committing crimes.

- People’s views on the legality of certain actions are influenced by the opinions of those around them.

- People become delinquent when they have more exposure to pro-criminal views than anti-criminal views.

- The frequency, duration, priority, and intensity of these associations affect the likelihood of criminal behavior.

- Learning criminal behavior follows the same mechanisms as any other type of learning.

- Criminal behavior is not solely determined by general needs and values; otherwise, everyone would behave criminally.

- People interpret their situations, which influences whether they follow or break the law. This explains why siblings raised in the same environment can have different behaviors.

Social Learning Theory

In the late 1990s, criminologist Ronald Akers combined ideas from operant conditioning and differential association theory to create his “social learning” or “differential reinforcement” theory (Akers, 1994). This theory looks at how people learn, keep, and change criminal behavior through rewards and punishments in social and non-social situations.

According to Akers, “differential associations” are the people you spend time with regularly, and “definitions” are the meanings you give to your actions. These meanings can be general, like religious or moral beliefs, or specific, like how you view a particular behavior, such as stealing.

In this theory, friends play a big role in shaping behavior. “Differential reinforcements” refer to the balance between the rewards or punishments you expect and what you actually get. For example, if a young person vandalizes a building and their friends praise them for it, they might keep vandalizing to get more praise, which reinforces the behavior.

Akers also talked about “imitation” or “modeling,” saying that people can learn by watching others being rewarded or punished. So, if someone sees others being rewarded for certain behavior, they might copy it, especially if it seems to bring good things.

Lastly, there are theories that focus on what is learned rather than how it’s learned. Subcultural theories say that people in different neighborhoods might learn different things about crime, police, government, or religion. For example, people in disadvantaged areas might learn ideas that justify criminal behavior or violence, while those in wealthier areas might learn different values. Where you grow up can shape what you learn about these things.

Control Theories

Control theories ask why more people do not engage in illegal behavior. Instead of assuming criminals have a trait or have experienced something that drives their criminal behavior, control theories assume people are naturally selfish and, if left alone, will commit illegal and immoral acts. Control theories aim to identify the types of controls a person may have that prevent them from becoming uncontrollable.

Early control theorists argued that there are multiple controls on individuals. Personal controls are exercised through reflection and following prosocial normative behavior. Social controls originate in social institutions like family, school, and religious conventions. Jackson Toby (1957) introduced the phrase “stakes in conformity,” which is how much a person has to lose if he or she engages in criminal behavior.

The more stakes in conformity a person has, the less likely they are to commit a crime. For example, a married teacher with kids has quite a bit to lose if they decide to start selling drugs. If caught, they could lose their job, get divorced, and possibly lose custody of their children. However, juveniles tend not to have kids, nor are they married. They may have a job but not a career. Since they have fewer stakes in conformity, they would be much more likely to commit crime compared to the teacher.

Optional Activity: Parenting Exercise

Parenting can be a challenging responsibility. They are supposed to teach children how to behave. Ideally, parents have control over their children in many ways.

- What are ways parents have “direct” control over their children?

- What are ways parents have “indirect” control over their children?

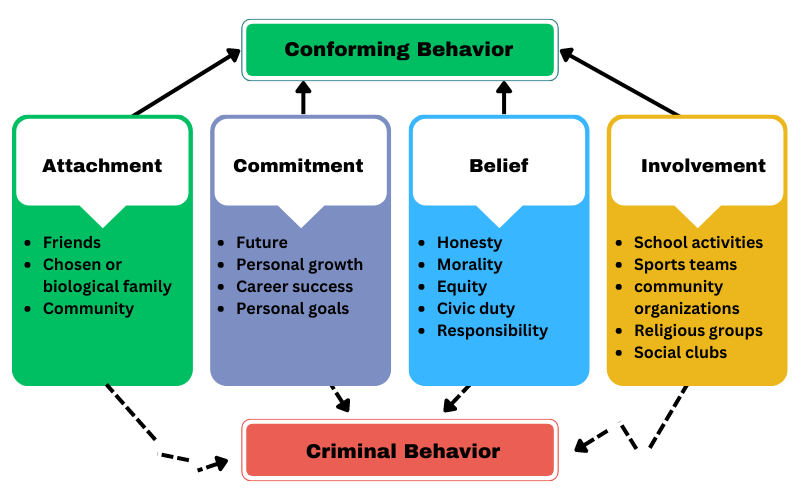

In 1969, Travis Hirschi argued that all humans have the propensity to commit crime, but those who have strong bonds and attachments to social groups like family and school are less likely to do so. Often known as social bond theory or social control theory, Hirschi presented four elements of a social bond: attachment, commitment, involvement, and belief.

Attachment refers to the affection we have towards others. If we have strong bonds, we are more likely to care about their opinions, expectations, and support. Attachment involves an emotional connectedness to others, especially parents, who provide indirect control. Commitment refers to the rational component of the social bond. If we are committed to conformity, our actions and decisions will mirror our commitment. People invest time, energy, and money into expected behavior like school, sports, career development, or playing a musical instrument. These are examples of Toby’s “stakes in conformity,” as shown in figure 5.8.

If people started committing a crime, they would risk losing these investments. Involvement and commitment are related. Since our time and energy are limited, Hirschi thought people who were involved in socially accepted activities would have little time to commit a crime. The observational phrase “idle hands are the devil’s worship” fits this component. Belief was the final component of the social bond. Hirschi claimed some juveniles are less likely to obey the law. Although some control theorists believed juveniles are tied to the conventional moral order and “drift” in and out of delinquency by neutralizing controls (Matza, 1964), Hirschi disagreed. He believed people vary in their beliefs about the rules of society. The essential element of the bond is an attachment. Eventually, Hirschi moved away from his social bond theory into the general theory of crime.

Control theories are vastly different from other criminological theories. They assume people are selfish and would commit crimes if left to their own devices. However, socialization and effective child-rearing can establish direct, indirect, personal, and social controls on people. These are all types of informal controls.

Critical Theories

Critical theories emerged in the United States during the 1960s and 70s. This period of intense political upheaval led to a generation of scholars questioning society and traditional crime theories. These critical theories share five key ideas.

- They emphasize the connection between power and inequality. People with power, whether political or economic, have a significant advantage in society.

- They argue that crime is a political concept. Not all criminals are caught, and those who are often face unequal punishment. The poor are disproportionately affected by law enforcement, while the wealthy receive lenient treatment.

- Critical theories suggest that the criminal justice system primarily serves the interests of the ruling class and capitalists.

- These theories point to capitalism as the root cause of crime. Capitalist societies often neglect the needs of the poor, prioritizing profit and growth over ethical considerations.

- Critical theories propose that the solution to crime lies in creating a fairer and equitable society, both politically and economically.

Feminist Theories

Feminist criminology started in the 1970s because the main criminology theories didn’t consider women’s experiences in the justice system. It’s a way of looking at crime and justice that focuses on gender differences. Feminist criminologists want to show how gender inequality and power imbalances affect crime, victimization, and how crime is handled.

They’ve criticized theories like Merton’s and social learning for being too focused on men and not recognizing how gender plays a role in crime. However, some feminist criminologists think these theories could still be useful if they’re adjusted to include both men and women. For example, Agnew’s strain theory now considers different sources of stress, including problems in relationships, which can be important for understanding why women might break the law. Also, life course theories look at events like having a baby, which could change whether someone keeps committing crimes or not.

Critical Race Theory

Legal scholars developed Critical Race Theory (CRT) in the 1960s and 1970s to analyze how racism motivates every major institution in society, including the law. This framework rejects the idea that it is possible for society to be “colorblind,” or that it is possible to resolve racial inequity by ignoring race itself. Instead, CRT considers the historical contexts in which social structures are created and protected, paying particular attention to the role of race and gender in shaping access to power and justice. CRT explains that racism is not merely individual bias or prejudice but is embedded in legal systems and policies (ABA, 2021). This theory provides valuable tools for examining how historical and contemporary injustices impact marginalized communities. Critics, however, argue that emphasizing racial differences and systemic issues can overshadow the progress that has been made and may lead to increased polarization (Gonzalez, 2020). Despite the debate, CRT remains a significant and influential framework in discussions about race, justice, and equality in America.

Social Reaction Theories

Social reaction theories focus on how people or institutions label, react to, and try to control offenders. These theories suggest that the labels we assign to individuals who commit crimes are significant because they influence how others perceive them. These labels are created through our interactions with others and carry a lot of meaning.

Not everyone who commits a crime is labeled a criminal, and labeling theories try to explain why. They say that what’s considered a crime can change depending on where and when it happens. For example, using marijuana might be legal in one state but not in another.

Labeling theorists also talk about the effects of being labeled as a criminal. If someone gets that label, they might start to see themselves that way too. John Braithwaite came up with the idea of “reintegrative shaming,” which is about forgiving and respecting the person who did wrong. This approach tries to bring them back into the community without keeping the label of “criminal” on them.

But in some places, like the United States, people are often treated with “stigmatizing shaming.” This means they’re punished and labeled as criminals, even after they’ve served their time. For example, some states make convicted offenders say they’re felons on job applications. This kind of treatment pushes people toward more crime. Reintegrative shaming, on the other hand, tries to change behavior by showing respect and understanding.

Licenses and Attributions for Other Modern Criminological Theories

Open Content, Original

Figure 5.8. The Stakes of Conformity by Trudi Radtke is in the Public Domain.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Other Modern Criminological Theories” is adapted from “5.9. Strain Theories, 5.10. Learning Theories, 5.11. Control Theories, 5.12. Other Criminological Theories” by Brian Fedorek in SOU-CCJ230 Introduction to the American Criminal Justice System by Alison S. Burke, David Carter, Brian Fedorek, Tiffany Morey, Lore Rutz-Burri, and Shanell Sanchez, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Modified by Sam Arungwa, Megan Gonzalez and Trudi Radtke, revised by Roxie Supplee, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, with editing for clarity.

“Feminist Theories” by Trudki Radke and Megan Gonzalez is adapted from “11.1 Foundations of Feminist Criminology” by Dr. Rochelle Stevenson; Dr. Jennifer Kusz; Dr. Tara Lyons; and Dr. Sheri Fabian in Introduction to Criminology, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Revised by Roxie Supplee, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, with editing for clarity.

Figure 5.7. Pavlov’s Classical Conditioning Diagram is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0.

An approach to criminology that emphasizes the use of scientific methods to study crime and develop solutions.

Theories that focus on how social and economic strain can push people into crime. These theories assume that human beings are naturally good but that bad things happen, which push people into criminal activity.

An explanation that attempts to make sense of our observations about the world.

Theories that focus on how people learn criminal behavior through processes of reinforcement and imitation.

A penalty imposed on someone who has committed a crime.

The criminal justice system is a major social institution that is tasked with controlling crime in various ways. It includes police, courts, and the correction system.

A system of rules enforced through social institutions to govern behavior.

Theories that explain why more people do not engage in illegal behavior. These theories often assume people are naturally selfish and, if left alone, would commit crimes.

A critical framework that examines the relationship between gender, crime, and justice.

Theories that focus on the social construction of crime and why not everyone who commits a crime is labeled as a criminal. These theories point out that definitions of crime can vary over time and place.