5 Important Situational Factors to Consider

L. Dee Fink (2013) reminds us that the initial phase of course design starts with consideration of important “situational factors” that can impact how well the class works. That is, designing a course that aims to provide students with significant learning experiences involves more than simply assembling a list of topics or a list of activities. In addition to content and teaching methods, other important factors include who students are and what kinds of experiences, interests, knowledges, skills, and aspirations they bring to the course. Similarly, instructors must consider who we are and what we are bringing into relationship with our students, the course content, and the methods we use. Plus, teaching and learning is part of larger contexts, including our academic departments and the university, our scholarly fields of study, our local communities and the wider social systems in which we are nested, and the historical legacies shaping these.

Important Situational Factors to Consider

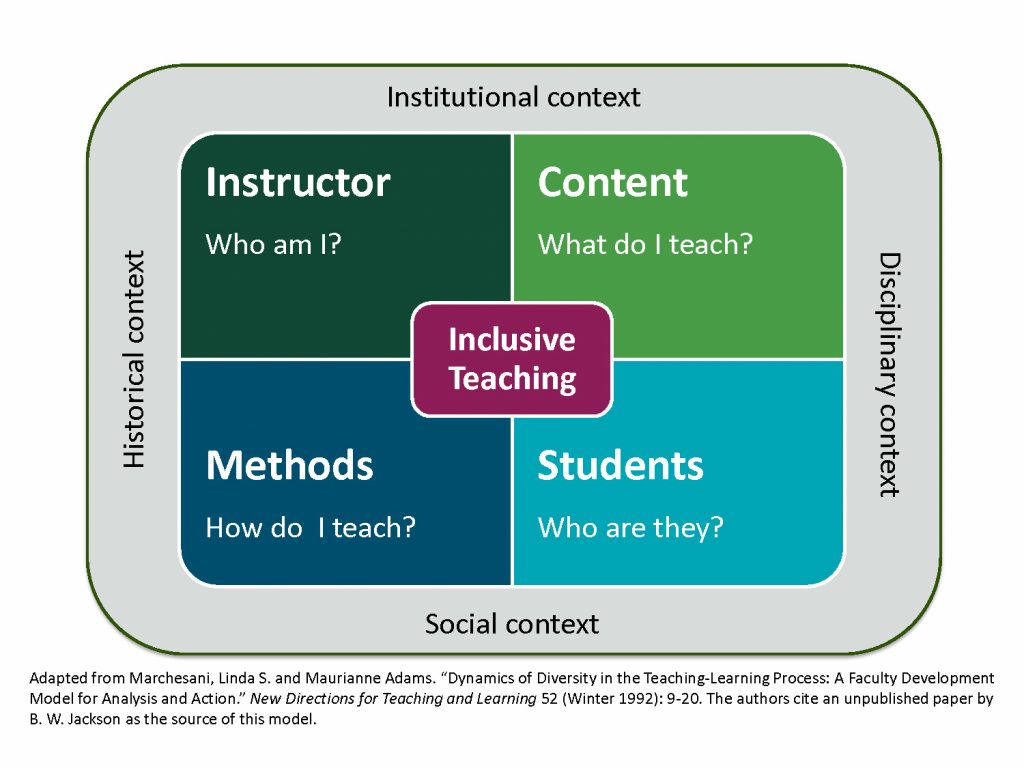

One way to explore the important factors noted above is to engage in reflection and consider how they work together as the necessary conditions for critically informed, inclusive teaching. The following graphic, adapted from Bailey Jackson (see Marchesani and Adams, 1992), articulates these factors and their interrelationships:

Specific questions to reflect on include the following:

Who am I? What assumptions do I bring to my teaching; what assumptions do I make about students? How has my own background shaped or enabled my intellectual journey? Do I find ways for my students to know me as a person with hopes, curiosities, even failures? Do they understand how to, and feel invited to, address and talk with me? How do my social identities position me in relation to my students, my institution, my field of study, etc.?

Who are my students? How will I find out? Do I know at least some of my students’ names? What strengths, anxieties, experiences, and identities do they bring to our work together? Can I make a place for those strengths, experiences, and identities to be clear assets in my classroom? Can I help relieve students’ anxieties or fears? What are my students’ own goals for their learning? How do they learn well? Do they feel anonymous? Like they don’t belong in my classroom? How can I counteract those feelings and build their sense of connection and agency?

What content and information will I convey? Does my course material reflect the diversity of the field, including the racial, ethnic, and gender diversity of its scholars and practitioners? More broadly, do I present knowledge as evolving and developed through heterogeneous conversation? Or are “non-traditional” topics and voices marginalized? Do I build a bridge between my content and my students’ lives—underscoring its possible urgency or beauty or value for them? Do I explicitly break down the process of expert thinking to invite them in?

What teaching methods will I employ? Am I using a range of strategies and modes of student engagement? What values do my methods signal to students? Do I draw on different kinds of talents and experiences my students bring to the class? Am I giving students low-stakes chances to practice, receive feedback, and reflect, and do I adjust my approach to respond to trends in their understanding? Do I engage with the scholarship of teaching and learning in my field? Am I aware of, and draw upon, anti-oppressive pedagogies pertinent to my teaching and learning context?

How are relevant contexts shaping my course? How has the history of my field or this particular course shaped what is included in its content, how it is taught, and which kinds of learners are centered in it, and which might be marginalized or excluded? How has this course evolved over time, and in what ways – and for what reasons – has it been altered or adapted to its current form? Which trends in my discipline, field of study, or other pertinent scholarly contexts should I be considering for how I organize and teach my course? Are there any departmental or institutional expectations or initiatives that might be influencing the aims, structure, or curricular elements of the course? What is happening socially, politically, economically, culturally, etc. in my community, region or nation that is related to the content of my course or might be affecting me or my students’ sense of wellbeing? How should I bring such contexts into the class?

Reflecting critically and honestly on the above questions can help identify gaps in our teaching or content knowledge and thus highlight areas for enhancing our own learning and skills; generate a list of priorities for emphasis in our course aims or organization and thus center certain questions or goals more strategically; and clear the ground for more informed, inclusive decision-making. For DIA courses in particular, mindful engagement with these situational factors can help make power dynamics more visible and navigable; it can also help uncover assumptions, ideas, structures, or practices that may seem “natural” or “obvious” but, upon further consideration, might be directing our teaching in certain ways that work against our intentions or interests, and those of our students (Brookfield 2017, 9-19). As Stephen Brookfield notes, “critically reflective teachers try to understand the power dynamics of their classrooms and what counts as a justifiable exercise of teacher power” (1997, 19). That is, DIA instructors can productively use virtually the same criteria their courses seek to enact for student learning – identities, power, structures, agency, reflection – as critical lenses for initiating the DIA course design process. Such critically reflective work can help instructors enhance their cultural and equity literacy and instructional fluency with DIA learning goals. This in turn bolsters instructors’ capacities to engage students in DIA learning.[1]

- For more background on equity literacy, see Gorski and Swalwell (2015). They identify four important abilities that underpin equity literacy: “Recognize even subtle forms of bias, discrimination, and inequity; Respond to bias, discrimination, and inequity in a thoughtful and equitable manner; Redress bias, discrimination, and inequity, not only by responding to interpersonal bias, but also by studying the ways in which bigger social change happens; Cultivate and sustain bias-free and discrimination-free communities, which requires an understanding that doing so is a basic responsibility for everyone in a civil society” (37). ↵