9 Modes of Inquiry in DIA Learning

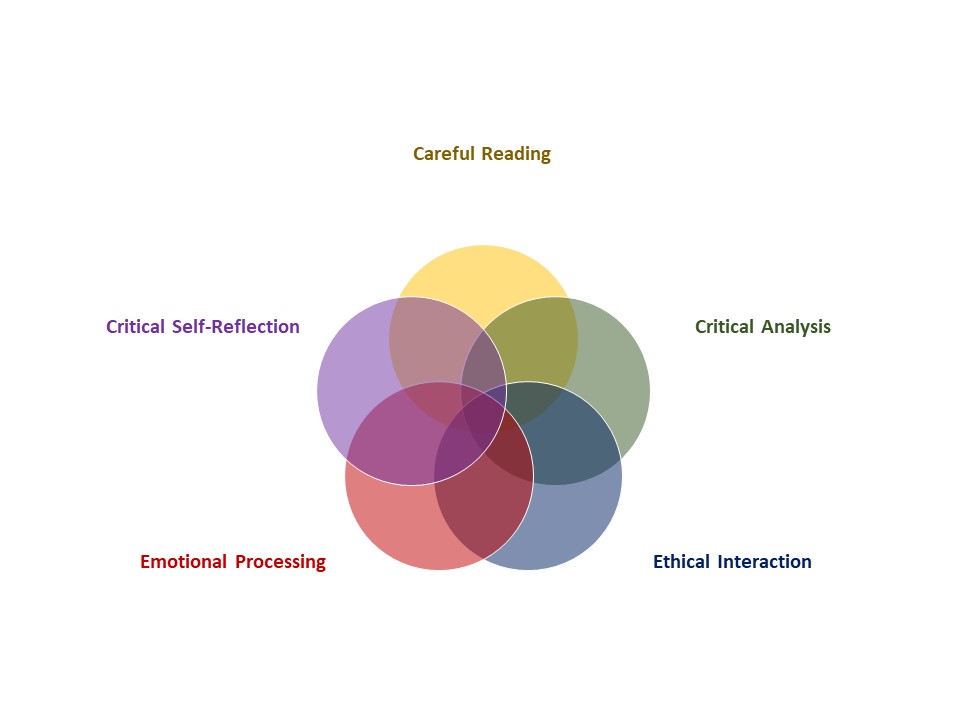

DIA learning engages students in five primary modes of inquiry or ways of learning. These modes of inquiry constitute the core skills of DIA learning. The modes of inquiry include the following:

The DIA requirement criteria articulate these modes. To reiterate, students in DIA courses are supposed to learn careful reading (i.e., engagement with texts from members of historically marginalized communities), critical analysis (i.e., scrutiny of intersecting aspects of identity, uses of power, and structures that perpetuate power) and either ethical interaction (i.e., listening and dialogue) or critical self-reflection (i.e., reflection on social identifications in relation to power). Because emotional labor is inherent to DIA learning, as discussed above, it is also included here because students will be engaged in emotional processing and because such processing, left unchecked or without constructive direction, can manifest in problematic ways that undermine learning.

Not every instructor may want to include all modes explicitly in their DIA course as something to facilitate or assess formally, and how these modes get used or which get more emphasis will depend on the aims of the course. Yet students are likely to be engaged in all these types of inquiry because of their considerable overlap. The question is, to what extent will they be guided to do so in an effective way that allows them to learn and practice the essential skills of cultural and equity literacy that these modes of inquiry enable?

We suggest that the most effective DIA courses will include at least some moments of focused student engagement in and through all five modes. However, including these modes in an explicit way in a course does not require an elaborate set of approaches for each. In fact, as suggested, they often overlap, such as critical self-reflection often involving emotional processing or careful reading entailing a form of ethical interaction with others. Moreover, they can be structured in rather simple ways, ideas for which are indicated below. Ideally, each mode can be scaffolded, modeled, and made part of a community building process. What we emphasize are the various options they provide instructors for developing activities, exercises, and assessments in and through which students can engage in practicing and demonstrating their DIA learning.

A few examples of ideas for how one could include these modes are indicated briefly here:

Careful Reading: Similar to “close reading,” careful reading emphasizes paying close attention to particular details and nuances of a text (this includes multiple forms of media and cultural expression), including interpretation of the social context of its production. In addition, it emphasizes charity and empathy, akin to what the DIA requirement calls “respectful listening,” which presumes an ability to notice one’s reactions and still suspend judgement until basic understanding of an other’s perspective or situation is reached. These emphases are crucial for respectful engagement with diverse others and their experiences, yet in a way that still allows for critical interpretation. Scaffolding and modeling play significant roles in helping students learn how to engage in this mode of inquiry, as does collaborative work as part of a discourse community. Instructors can, for example, provide a list of basic guiding questions that help orient students to various texts and their contexts, allow time in class for small group reading and discussion of key passages (or discussion of a video, photo, etc.), or have students turn in short reading or video viewing responses, such as having them identify three significant key issues, two confusing parts, and one question they wish had been addressed. Numerous resources and activities can enliven how students engage in the inquiry of careful reading.

Critical Analysis: Critical examination of power and how it shapes society is at the heart of DIA learning. Instructors will have students engage in such inquiry using a variety of specific methods and approaches, depending on the field of study emphasized in the class or the nature of the content at hand. That is, there is no special DIA method for the particular form that critical analytical work will take. However, whatever form it does take, such work will focus on the study of power and how it shapes inequalities – this focus is common to all DIA courses and crucial for development of cultural and equity literacy. The dynamics of scaffolding, modeling, and collective discourse can heighten the effectiveness of whatever forms critical analysis takes in a class. Modeling can make a complex process more transparent to students, while scaffolding can break this process into smaller chunks that students can practice and develop over time. And collaboration with peers as part of a critical discourse community can yield a plethora of insights and perspectives. Concretely, instructors can provide “critical questions” checklists, such as the “Ultimate Cheatsheet for Critical Thinking,”[1] prepare handouts that outline specific inquiry steps to take and indicate key areas to consider, facilitate short “believing and doubting” or “pro and con” exercises, organize a class debate or “article on trial” presentation, among numerous other possibilities.[2] These ideas emphasize modeling and structuring of the process of analytical skill building and providing basic tools to practice with, thus making explicit what to do and how to do it. Moreover, they make visible that critical inquiry is a collaborative endeavor among participants in a discourse community, one that students are being invited into during a DIA class. Providing specific tools and resources that students are to use and practice, also “presses” them to think and work and define reality in different ways, rather than simply relying on prior conceptions or ingrained habits

Ethical Interaction: Ethical interaction can take a variety of forms, but at a basic level in a DIA class, it entails respectful listening and civil discussion. Learning to listen is an important skill that one must learn and, more importantly, practice. This requires structured exercises, which can be quite simple. For example, instructors can have students get in pairs, with one student sharing a short commentary that the other student then paraphrases; then they can switch. A variation is to have one student share an insight (summary, opinion, explanation, etc.) while the other student listens and identifies three terms the other student has used, which they feel best represent the key points or indicate what is most significant about what was shared. In a whole group discussion, students can first summarize what a previous student has said about an issue, then extend this insight or offer their own take on it. Of course, instructors can model respectful listening by mirroring back what they hear from students, paraphrasing, asking gentle question to seek clarification or draw more out from a student, and so on. Again, a variety of resources exist to provide ideas. Regarding civil discussion, the class can generate clear ground rules, as discussed above, and students and the instructor can hold each other accountable to them and regularly revisit them and revise as necessary. Structuring a variety of discussions on important topics and issues can also help, creating multiple types of occasion for practice.[3] Some instructors might introduce a formal model for ethical engagement and have students practice interacting in this way. Ethical interaction also includes how students engage in their careful reading, as suggested above, and in their research practices, for example use of decolonizing research methodology (Smith 2012). Once again, scaffolding, modeling and community building can play crucial roles in helping students learn through this mode of inquiry.

Emotional Processing: The presence of emotions is inevitable in a DIA class, as discussed above. Although the DIA requirement does not articulate emotional work as a learning outcome, instructors will need some plan of action for addressing student emotions. Here the suggestion is to treat emotional processing as an essential mode of inquiry for DIA learning. Discussion of feelings and opportunities to reflect on them are thus important to build into the class. Instructor modeling can be as simple as regularly expressing how one feels about issues at focus in the class, or a more elaborate disclosure of one’s evolving feelings in the process of coming to awareness about power and one’s relationship to it. A structured process for students can be as simple as a journal that students keep, which can be combined with more focused self-reflection on identity and power, as discussed in the next mode of inquiry. Journal entries could respond to questions such as “What is going on for me in class?” “Why am I feeling this way?” “What am I really angry/sad/anxious/etc. about?” “What am I afraid of?” “Why do I get upset when this issue comes up?” And so forth. Journals can be shared with instructors or remain exclusively for students to use and read themselves. Emotional processing can also overlap with critical analysis, for example having students identify a particular emotion arising for them and doing research that examines it more closely, including possible tools for transforming it in a productive way. Such work could take the form of student papers or, better yet, presentations or a gallery walk exercise that provides students opportunities to learn from their peers and realize that emotions are not merely personal but social. Such research and assignments could be collaborative in nature, including group projects or group study circles, out of which students write individual papers or other forms of assessment. These same ideas can be used for critical analysis work, too, but the point is to indicate that emotional processing can be structured and even assessed, and thereby inform student learning in a significant way. Scholars such as Young and Davis-Russell (2014), Froyum (2014), and Matias (2016) outline a variety of ways for engaging students in emotional labor in productive ways that include community building considerations and complement other DIA modes of inquiry. TEP also has available a resource handout on “Strategies for Engaging with Difficult Topics, Strong Emotions, and Challenging Moments in the Classroom,” which includes activities and exercises for engaging emotions and discomfort. Additional strategies can be found at TEP’s Teaching in Turbulent Times Toolkit.

Critical Self-Reflection: One significant challenge of self-reflection in a DIA class is that it involves having students turn the methods of critical analysis back on themselves so that they can scrutinize their own relationship to power. This makes self-reflection critical, insofar as students are challenged to identify and acknowledge their positionality in a network of power that shapes unequal relationships; such awareness forms a basis for how one will interact with others and with the systems of power that produce unequal outcomes. Such knowledge is crucial for engaging others ethically and with care and empathy. As discussed above, instructor modeling of such critical reflection – for instance, disclosing how one has come to awareness of one’s own relationship to power or sharing ways that one uses such knowledge to promote change – is vital for opening the space of vulnerability and trust required to do this work and share it in some form (hooks 1994, 21). Creating a scaffolded structure of regular self check-in and reflection is also helpful. This can take the form of journal entries in which students respond to guided prompts that can be designed to elicit their unfolding experience of learning about their own social identifications and relationship to power, including how they are feeling. Such entries could form the basis for a term-long creative project or presentation in which students share a narrative of change over time in their awareness and understanding. Another option is to have students complete short in-class writing exercises on a periodic basis, in which they respond to questions about their experiences engaging with content, lectures, class discussions, or other class activities, and how these might be influencing their evolving understanding. Students could also complete a series of critical incident questionnaires, an anonymous survey about their learning experiences, which thus generate a collective picture of classroom community dynamics, revealing invaluable insights for the instructor. Many format options for critical self-reflection exist and can be adapted for the particular aims of critical self-reflection indicated in the DIA requirement. Of course, instructors can supplement and support such reflection with more general reflective approaches, such as basic metacognitive teaching and learning activities.

Because it is a mirror of the social reality of the United States, the content of DIA courses can be very challenging cognitively and emotionally for students to learn, especially given the context of a society (including higher education spaces) that does not often engage in discussing or addressing such content openly or with explicit attention to the power dynamics involved. By calling up the kinds of inquiry that allow students to engage DIA content with a more open mind and caring heart, in collaboration with others, and with more understanding of power dynamics, including one’s own positionality and potential routes for action, instructors can signal clearly the promise and value of DIA learning. In turn, by organizing specific opportunities for students to practice these modes of inquiry, learn how they interconnect, and understand the standards of rigor indicative of success, instructors can make more visible what kind and quality of work is needed for students to develop cultural and equity literacy skills moving forward in their lives.

- Numerous sources online offer this resource as a downloadable PDF – one need only Google it. ↵

- See Barkley (2010) for a plethora of student engagement exercises, each with detailed instructions and variations. ↵

- TEP offers many discussion resources at https://teaching.uoregon.edu/resources/classroom-discussion-resources ↵