Lead Poisoning in the Modern Community by Mena Moran

Lead Poisoning Background

Throughout the centuries and recent decades, lead has been utilized for paint, gas, sheet lead, solder, pipes, and ammunition. While these materials have been used regularly, lead is exceedingly toxic, and symptoms to the body and the brain can be detrimental, leading to convulsions, comas, kidney failure, reproductive issues, nervous system disruptions, anemia, cancer, and death. Neurologically, lead is known to slow growth and development and contribute to neurological disorders in adulthood (i.e. depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and the lowering of IQ). The measure of lead in the blood (blood lead levels or BLLs), have been high due to this overuse of lead—the average BLL decreasing from 15 micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood (µ/dL) in the 1970s to 5 µ/dL in the 1990s (“Lead Management”, 2011). Because lead is harmful to development, the toxin especially impacts children.

In the city of Flint, Michigan, beginning in 2014, 100,000 people were affected by lead poisoning before officials took action. As a low-income city, the governor of Michigan, Rick Snyder, began to draw water from the Flint River to conserve money in 2013. For many years, the Flint River was known to be toxic and rich in pollutants, and when the river began to supply Flint’s water, elected officials ruled that the water need not undergo treatment. As if this weren’t contaminated enough, lead pipes were used to further distribute the water, and “[d]ue to the water’s poor quality, lead began to seep from the pipes into the city’s water supply” (“Flint Water Crisis”, 2022). In the crisis, clean water was not available until 2019, and many citizens acquired Legionnaires Disease (a form of pneumonia developed by Legionella bacteria), among other mental and physical health tolls, such as rashes and hair loss—there were a total of twelve deaths accounted for. Around this time, the African American population of the city was 57% in 2015 (Sim, 2016). In 2021, a lawsuit was initiated against Michigan, Flint, and officials for duty negligence in the crisis. Similarly, in Wisconsin, in 2018, one quarter of children were tested for lead poisoning, all under the age of six, and accordingly had BLLs “over double the national average” (Shain, 2022). In Milwaukee, Wisconsin, over 40 percent of the water lines contain lead, and half of the city’s households are rented, limiting residents’ choices in the matter of replacement. Costs for replacing lead pipes in Milwaukee have ranged up to $5,000 for just one pipe to $27,000 for a minimal replacement. The CDC claims that no lead level is considered safe, and although this is the goal set by the EPA, the maximum amount of lead permitted in water is 15 parts per billion.

Lead and Schools

A Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) study in 2003 “found that 28 percent of licensed childcare centers in the U.S. contain lead-based paint” (“Lead Management”, 2011). This number has declined due to the raised awareness of lead poisoning, but the problem continues to persist. 74 Federal GSA daycare centers that closed due to the COVID-19 Pandemic were examined after they had reopened—95 percent had not been tested for lead. When advised to test, 50 percent complied, and 7 percent of this half proved to have exceedingly high lead levels (Davidson, 2022). Public schools are increasingly providing lead health screenings for children, who should not have above 10 µ/dL in their blood. Unfortunately, only 43% of public schools in the US test for lead, and of those that test, 37% test positive for elevated lead levels in water (“K-12 Education: Lead Testing of School Drinking Water Would Benefit from Improved Federal Guidance”, 2018) In one study by the National Library of Medicine, it was concluded “that 13% of reading failure and 14.8% of math failure can be attributed to exposure to blood lead concentrations” in Chicago public schools alone (Evens, Forst, Hryhorczuk, et al, 2015). Nationally, it was estimated in 2016-2017 that about three-quarters of school districts had not examined schools for lead-based paint” (Murray & Schatz, 2019). One theory that has continued to gain approval in the 21st century is the correspondence between lead exposure and crime rates. Author Kevin Drum looks at multiple studies showing levels of crime in correlation with lead. The crime rates in the U.S. appear to interact with blood lead levels significantly, peaking in the 1960s and 70s, and declining until the 1990s. You can view the figures in Drum’s article here. (Drum, 2013) With generations of children inhabiting environments with high levels of lead, and with childrens’ propensity to put objects in their mouths (such as lead paint chips and/or toys), neurological disorders are more likely to develop, which may have helped to increase crime during specific time periods.

Redlined and Leadlined

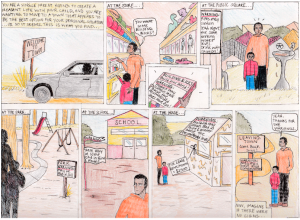

The disappointing truth about where lead poisoning is most distributed involves a long and grueling history of redlining and racism. The effects of redlining African Americans and minorities into segregated areas continues to play out today, as many minorities are low-income and inhabit houses built before 1978, which was the year lead paint was banned in the construction of homes and products. In 2021, in the U.S., it was counted that African Americans had a 21% poverty rate, non-hispanic white populations at 9.5%, and hispanic at 21%, according to the Kaiser Family Foundation (“Poverty by Race/Ethnicity”, 2021). The BLL of non-hispanic Black children has been proven to be significantly higher than that of non-hispanic white kids, at a level of 4.0 μg/dL versus 3.0 μg/dL, and Black children are more likely to live in urban areas (Bravo, Zephyr, Kowal, et al, 2022). In correlation, it is estimated that detectable levels of lead in the blood have tested positive for 58 percent of Black children, 56 percent of Hispanic children, and 49 percent white children nationally (Hauptman, Niles, Gudin, et al, 2021). This also takes into account that Black children are six times more likely to have elevated BLLs than white children in houses built before 1978 (Knight, 2020). Additionally, although lead poisoning is a larger social issue than one may think, it also remains an environmental one as well: lead continues to settle into soil and groundwater permanently. Lead does not decay or biodegrade, making the environment more toxic to inhabit.

Figure: “Redlined & Leadlined”

Despite these concerning events, there have been a number of acts throughout the decades that have attempted to combat lead poisoning, from the 1974 Safe Drinking Water Act, in which the EPA regulates the amount of lead in water for housing and facility development. The Lead Contamination Control Act of 1988 ensures education of lead, as well as health screenings in schools. The Residential Lead-based Paint Hazard Reduction Act (1992 – Title X) monitors the amount of lead paint in housing and construction. Consumer Product Safety Improvement Act (2009) regulates lead in products such as toys, and the Toxic Substances Control Act requires reports and records of lead contamination. You can view more acts to combat lead poisoning at the EPA webpage (“Lead Laws and Regulations”, 2022).

Works Cited

Bravo, Mercedes A. et al. “Racial residential segregation shapes the relationship between early childhood lead exposure and fourth-grade standardized test scores.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 15 Aug. 2022, https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2117868119#supplementary-materials

Davidson, Joe. “Kids at risk of lead contamination in federal child care, watchdog says.” Washington Post, 30 Sep. 2022, p. NA. Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A720309859/OVIC?u=lbcc&sid=bookmark-OVIC&xid=23cca22d. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

Drum, Kevin. “America’s Real Criminal Element: Lead.” Mother Jones, 2013, https://d32ogoqmya1dw8.cloudfront.net/files/integrate/teaching_materials/lead/lead_crime_2013.pdf

Evens, Anne et al. “The impact of low-level lead toxicity on school performance among children in the Chicago Public Schools: a population-based retrospective cohort study”, National Library of Medicine, 7 Apr. 2015, https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25889033/#:~:text=We%20estimated%20that%2013%25%20of,dL%20in%20Chicago%20school%20children.

“Flint Water Crisis.” Gale Opposing Viewpoints Online Collection, Gale, 2022. Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints, link.gale.com/apps/doc/WAZOPU131154091/OVIC?u=lbcc&sid=bookmark-OVIC&xid=f1f43c9a. Accessed 25 Nov. 2022.

Hauptman, Marissa et al. “Individual- and Community-Level Factors Associated With Detectable and Elevated Blood Lead Levels in US Children: Results From a National Clinical Laboratory.” JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(12):1252–1260. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2021.3518 https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2784260

“K-12 Education: Lead Testing of School Drinking Water Would Benefit from Improved Federal Guidance.” U.S.Government Accountability Office, 5 Jul. 2018, https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-382

Knight, Ben. “Lead Poisoning Reveals Environmental Racism in the U.S.” EcoWatch, 7 May 2020, https://www.ecowatch.com/lead-environmental-racism-2645941587.html

“Lead Laws and Regulations.” United States Environmental Protection Agency, 18 Aug. 2022, https://www.epa.gov/lead/lead-laws-and-regulations#:~:text=Lead%20is%20a%20pollutant%20regulated,Recovery%20Act%20(RCRA)%2C%20and

“Lead management.” Environmental Encyclopedia, edited by Deirdre S. Blanchfield, Gale, 2011. Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints, link.gale.com/apps/doc/CV2644150796/OVIC?u=lbcc&sid=bookmark-OVIC&xid=e43c9f75. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022.

Murray, Patty and Schatz, Brian. “GAO-19-461R, K-12 Education: School Districts’ Efforts to Address Lead-Based Paint.” U.S. Government Accountability Office, 9 Jul. 2019, https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-19-461r.pdf

“Poverty Rate by Race/Ethnicity.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 2021, https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/poverty-rate-by-raceethnicity/?currentTimeframe=0&sortModel=%7B%22colId%22:%22Location%22,%22sort%22:%22asc%22%7D

Shain, Susan. “A Lead Problem Worse than Flint’s.” Gale Opposing Viewpoints Online Collection, Gale, 2022. Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints, link.gale.com/apps/doc/FWTPHB028692899/OVIC?u=lbcc&sid=bookmark-OVIC&xid=402034a9. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022. Originally published as “A Lead Problem Worse Than Flint’s,” In These Times, 16 Sep. 2021.

Sim, Bérengère. “Poor and African American in Flint: The water crisis and its trapped population.” 2016, http://labos.ulg.ac.be/hugo/wp-content/uploads/sites/38/2017/11/The-State-of-Environmental-Migration-2016-76-102.pdf

Other viewed/recommended sources not referenced in text:

“African American Neighborhood Built On Toxic Lead Contamination.” Youtube, uploaded by Rebel HQ, 2016, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KNMOitVOw9I

“Lead in Toys Brochure.” Department of Health and Human Services, https://dhhs.ne.gov/Lead%20Documents/LeadInToys.pdf

“Scientists link childhood lead exposure to adult mental health problems.” Living on Earth, 14 Jan. 2022, p. NA. Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints, link.gale.com/apps/doc/A691424430/OVIC?u=lbcc&sid=bookmark-OVIC&xid=74aeb0ef. Accessed 27 Nov. 2022.