Lead in Minority Communities by Luke Scovel

Lead in Minority Communities

Introduction

Lead has been a problem in the U.S. for centuries. Lead was ubiquitous in paint and pipes until 1978, when it was banned for use in new housing (EPA, 2023). A large portion of low-income housing is old and deteriorating, which causes increased risk for anyone living in these areas (Chen et al., 2022). This is an example of an environmental injustice because it disproportionately affects low-income and minority communities. Children are especially affected due to higher absorption levels and possible developmental defects (Henderson & Wells, 2021). Small amounts of lead are not harmful for adults, but any amount of lead is harmful for children (Chen et al., 2022). People of color, and more specifically children of color, are much more likely to be exposed to high levels of lead from inadequate housing. This project will provide examples on how lead can affect minorities and children, and detail what the current regulations are and how they should be changed.

Results

From 1999 to 2019, the percentage of housing units with lead paint declined from 38 million to 35 million, but the number of housing units that contained deteriorating lead paint increased from 13.6 million to 18.2 million (Jacobs & Brown, 2023). Only 11.1% of households that received government housing assistance had higher levels of lead, while 19.9% of households that did not receive assistance had higher levels of lead (Cox et al., 2021).

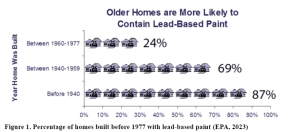

Figure 1. Percentage of homes built before 1977 with lead-based paint (EPA, 2023)

While the number of homes that were constructed containing lead declined leading up to the federal ban in 1978, millions of homes still contain lead that was never removed.

58% of children from majority black areas and 56% of children from majority hispanic areas had detectable blood lead levels compared to 49% from predominantly white neighborhoods (Chen, 2022). Childhood lead exposure has been linked to “cognitive impairments and behavioral disorders in childhood, as well as criminal arrests, psychopathology, and reduced earnings in adulthood” (Braun et al., 2021).

Example

The Freddie Gray case is one example of police brutality on a black person that has been linked to increased lead levels during childhood. Freddie Gray grew up in extreme poverty in Baltimore where he was exposed to significant amounts of lead due to contaminated housing. Tests taken between 1992 and 1996 showed that Gray had significant amounts of lead in his blood, which led to a lawsuit against their landlord. As children are known to have increased mental deficiencies when exposed to lead, it is thought that this may have contributed to Freddie’s behavior issues and led to his death at the hands of police in Cleveland, Ohio (Henderson & Wells, 2021).

Current lead laws are insufficient

Lead regulations are weak at the federal level. The 1978 law banned any new usage of lead in houses, but millions of homes already contained lead that wasn’t required to be removed. It wasn’t until 1992 that actual regulations were put into place on how the government would go about removing lead from contaminated housing, but they still didn’t require any kind of mass testing for housing built before 1978 (Chen, 2022).

As stated before, any amount of lead exposure can be harmful for children. In 2019, the EPA updated its lead level standards after removal to 10 micrograms (µg) of lead in dust per square foot (ft2) for floor dust and 100 µg/ft2 for window sill dust from 40 and 250 μg/ft2 respectively (EPA, 2023). According to a study done on the EPA’s updated lead regulations,

“The 2019 EPA dust lead hazard standard does not adequately protect children from residential dust lead hazards… there was a 45% and 33% higher risk of having blood lead concentrations ≥5 μg/dL at the newly revised floor and windowsill dust lead hazards of 10 and 100 μg/ft2 compared to the HOME Study standards of 5 and 50 μg/ft2” (Braun et al., 2021).

These updated regulations were a step in the right direction, however lead still poses a large risk to children.

What should be changed

The main problems that need to be addressed to resolve the larger issue are government provided low-income housing and lead regulations. As shown by the statistics I have provided in this report, government housing assistance resulted in lower lead exposure risk. Increased funding for government housing programs should be considered. The other large problem within this issue is inadequate regulations for when lead should be removed from contaminated housing. Currently there is no large-scale program to investigate old housing for lead contamination. More stringent regulations on the levels of lead within housing should be implemented (Braun et al., 2021).

Conclusion

In this project, I examined scientific data from multiple sources to better understand and analyze the problem of lead contamination in minority communities. Lead contamination in housing has led to disproportionate, life-long harms on minority and low-income communities all over the U.S, perpetuating the cycle of poverty for as long as these people are unable to afford better housing and regulations are insufficient to protect them from hazards. This ends up resulting in a generational issue for minorities as they are unable to escape from the cycle of poverty due to increased financial and social burdens. The U.S. needs better environmental justice regulations for these communities. From my research I have determined that a nationwide survey of housing built before 1978 should be undertaken to identify housing that contains possible hazards, and when contamination is found it should be completely removed. Improved housing assistance programs would also be beneficial to these communities by providing safer housing with less of a financial burden.

References

Chen, K. (2022). A Community Voice on Lead Paint: Examining the Role of Cost-Benefit Analysis in Environmental Regulation. Ecology Law Quarterly, 49(2), 437–470. https://www.ecologylawquarterly.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/49.2_Chen_Internet.pdf

EPA. (2023). Lead. Environmental Protection Agency. https://www.epa.gov/lead

Jacobs, D. E., & Brown, M. J. (2023). Childhood Lead Poisoning 1970-2022: Charting Progress and Needed Reforms. Journal of Public Health Management & Practice, 29(2), 230–240. https://doi-org.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/10.1097/PHH.0000000000001664

Braun, J.M., Yolton, K., Newman, N. et al. Residential dust lead levels and the risk of childhood lead poisoning in United States children. Pediatr Res 90, 896–902 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41390-020-1091-3

Henderson, S., & Wells, R. (2021). Environmental Racism and the Contamination of Black Lives: A Literature Review. Journal of African American Studies, 25(1), 134–151. https://doi-org.ezproxy.libweb.linnbenton.edu/10.1007/s12111-020-09511-5

Cox, D., Dewalt, G., O’Haver, R., Biell, J. et al. (2021). American Healthy Homes Survey II Lead Findings. Department of Housing and Urban Development. https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/HH/documents/AHHS%20II_Lead_Findings_Report_Final_29oct21.pdf?ref=tome-control-de-su-salud