Historical, Collective, & Individual Professional Identity Narratives

Erin Trine

Introduction

This section begins with the premise that “learning to become a professional involves not only what we know and can do, but also who we are (becoming). It involves integration of knowing, acting, and being in the form of professional ways of being that unfold over time” (Dall’Alba, 2009, p. 34). How to best support students in this transformative process so they are ready to contribute to their profession and communities is one of the great questions of education. Interpreter educators aspire to support students in their development into professionals who consumers can trust and rely upon to practice with appropriate ethics, competence, and professionalism. Though, the ways this has been attempted has shifted over the years, historically, interpreter education has focused heavily on what students must do to function as interpreters (Ball, 2007) and less on what students must become as professional interpreters. While understandable from the historical context of our field, and not unique to interpreting (Dall’Alba, 2009), this is a phenomenon worth noting for such a relational profession.

Researchers in the fields of education, counseling, and medicine have explored professional identity in emerging professionals for decades (see Andersen, 1995; Connelly and Clandinin, 1999; Damasio,1999; Van Manen,1990; Winslade, J., Crocket, K., Monk, G. & Drewery, W., 2000 amongst others), but research in this area is just recently emerging in interpreting studies (Harwood, 2017; Hunt, 2015). Additionally, Annarino and Hall (2013) found that interpreters need to feel connected to the larger profession in order to value ethical choices in their practice. Who pre-professionals believe themselves to be and how they see themselves situated within the larger context of the profession will have an impact on them as individuals, the profession as a whole, and especially on the consumers they serve. Recognizing this compels us to explore this topic further. In this section we will endeavor to examine and explore the historical, collective, and individual professional identity narratives of the interpreting field in the hopes of fostering a deeper understanding of the narratives we have created as a profession and their impact, as well as move forward together in creating new narratives as individuals, a field, and a community.

The objectives of this section are to:

- Be reflective of the transformational journey required for students to become professionals and have that guide future approaches to preparing the new generations of interpreters.

- Explicate the historical narratives of what interpreting is, who interpreters are, and how that impacts the field and consumers.

- Examine the current narratives in the interpreting field and how that impacts the field, interpreting students, and consumers.

- Analyze what narratives students hold about their interpreting and ability to do the professional work.

- Discuss how experiences impact the professional identity narratives of interpreting students, interns, and working interpreters.

- Consider how interpreting students can approach their identity narratives analytically and accurately to support them in moving toward professional practice.

- Emphasize the importance of recognizing and addressing these narratives through appropriate practices (may include DC-S Supervision, data comparison, and counseling).

- Offer example activities to support students in examining their professional identity narratives.

Professional Identity

In this section we will use a broad understanding of professional identity, in line with Gibson, Dollarhide, and Moss’ (2010) claim that “contemporary definitions of professional identity seem to revolve around three themes: self-labeling as a professional, integration of skills and attitudes as a professional, and a perception of context in a professional community” (p. 21) Contributing authors may offer additional framing for their chapters. This understanding of the term is not about self-confidence, per se, but accurate self-awareness. For example, a healthy professional identity would not result in a student or interpreter being overly confident, but realistically aware of their abilities and limitations professionally. To put it another way: a healthy professional identity in a capable interpreter would produce the opposite of imposter syndrome; a healthy emerging professional identity in an interpreting student would produce accurate recognition of what has been mastered, what has not, and the work needed to move them deeper into the practice of a professional, the process of which allows them to become one. Due to the ontological nature of professional identity, it is not something that an individual could simply claim without doing the work of genuinely becoming a professional.

We also consider professional identity development to be a perpetual ontological exploration that requires vulnerable reflection, intentional work, and integrity. This includes alignment in what the individual recognizes about their professional abilities, the actual skills, mindsets, and attitudes they embody as a professional, and what their colleagues and consumers recognize. Rather than have students that adhere to a static deontological framework of how interpreters should behave, we desire students to truly become professionals and out of their professionalism express values, attitudes, and expectations that align with those of the professional community—esse quam videri. In interpreter education, this undertaking is a co-constructed process that requires students and educators to partner in the process of students becoming professionals:

When we take seriously the ontological dimension of professional education and the ambiguities of learning to become professionals, professional education can no longer stop short after developing knowledge and skills. Acquisition of knowledge and skills is insufficient for embodying and enacting skilful [sic] professional practice, including for the process of becoming that learning such practice entails. Instead, when we take account of ontology, professional education is reconfigured as a process of becoming; an unfolding and transformation of the self over time (Dall’Alba, 2009, p. 42).

This is not only true of the students’ professional identities, but of the interpreter educators’ as well. This perpetual “unfolding and transformation” (Dall’Alba, 2009, p. 42) process is integral to the practice and professional identity of interpreter educators as well as the ability to invite students to join them in this practice. Doing so supports student becoming and also creates space for a collective unfolding toward professional identity as a community and, hopefully, eventually as a field. One of the ways we employ in this practice is through engagement with narratives.

Narrative Inquiry

Narrative inquiry may be incorporated into a variety of qualitative research methods (e.g., phenomenological, case studies, ethnographical and autoethnographical) and may be considered as a methodology itself (Clandinin, 2016). This approach includes a focus on examining lived experiences through narrative form, or storying. For example, in their chapter Hamilton and McAlpine (2019) employ a narrative inquiry approach in which the authors recount personal experiences in narrative form and then analyze their stories for a deeper understanding of the impact and meaning that they internalized from those experiences and how each one contributed to their professional identities.

Readers may also be familiar with the work of Dr. Brené Brown (2010), whose popular work with narrative inquiry includes the power of deeply engaging with our own narratives to move to a place of health and whole-hearted living. Brown is not alone in lauding the powerful effect of examining our lived stories. From the field of counseling, Balatti, Haase, Henderson and Knight (n.d.) state that storying is vital to the development of identity based on neurological research examining how people continually reconstruct their self-image from lived and anticipated experiences. Also from the counseling field, Winslade (2002) explains that storying enables students to connect and integrate aspects of their professional identity through articulating who they are as a professional. He believes such articulation involving “fostering self-descriptions consistent with the performance of the values and skills of…practice” (Dulwich Centre, n.d., para. 15 ) is required for the process of developing professional identity. From this perspective, not only is storying useful for professional identity development, but professional identity development cannot occur without a form of storying aligning one’s self-concept with professional expectations.

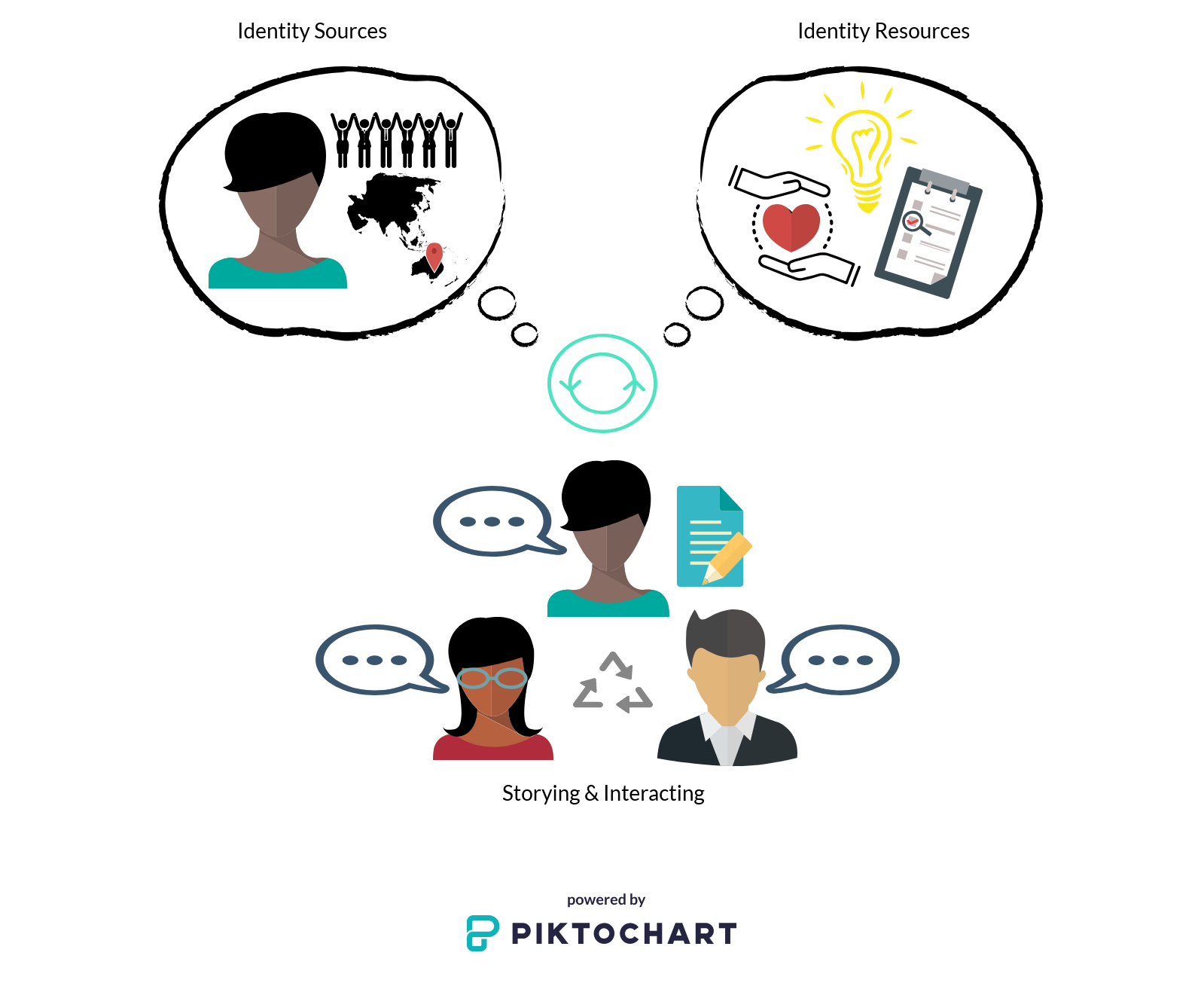

Balatti, Haase, Henderson and Knight (n.d.), from the field of Education, describe the learning identity framework (Falk and Balatti, 2003) to explain how storying impacts identity formation. The framework includes three elements: The first is “identity sources,” which includes any aspects of the intersectional identity of the individual as well as context and place of the individual (Balatti, Haase, Henderson & Knight, n.d., p. 2 ). The second is “identity resources” which includes “behaviours, knowledges, beliefs and feelings,” but also a sense of self-confidence and belonging (Balatti, Haase, Henderson & Knight, n.d., p.3). The third is “storying and interaction,” through which identity is formed, re-formed, and co-constructed (Balatti, Haase, Henderson & Knight, n.d., p.3). Balatti, Haase, Henderson and Knight (n.d.) explain that through interaction within the framework these elements constantly inform each other to shape an ever-evolving identity.

See Figure 4.1 below for a reimagined version of this framework as it relates to an Interpreting context.

Figure 4.1: Learning Identity Framework Adapted from Falk and Balatti, 2003

In Figure 4.1 the identity sources would be the intersectional identity of the individual interpreting student/interpreter, the place she is located, and the profession of interpreting. The identity resources would include the degree to which the interpreting student/interpreter sees herself as an interpreter and as belonging to the professional community; controls she brings to the work; educational standards such as that of an interpreting program; professional standards such as the Entry-to-Practice Competencies (Witter-Merithew & Johnson, 2005), national certification requirements, local credentialing/licensing requirements; consumer expectations; etc. Storying and interaction occurs in community and individually, and the elements inform one another in a continual loop. This becomes a virtuous cycle of perpetual reformulation of the individual’s professional identity as it is strengthened through reflection, storying, and interaction.

The impact of storying and interaction in this framework emphasizes the importance of interpreter educators engaging in co-constructive, or co-authoring, storying practices with students to support their professional identity development. As members of the identity resources community, interpreter educators have the ability to validate a students’ belonging to the community (when appropriate) and to process their narratives with them through storying and interaction such as classroom discussions and assignment feedback. Narrative inquiry approaches to exploring professional identity within our field offer exciting opportunities to support students and colleagues in becoming the healthy professionals consumers need and expect.

It is important to note that although this framework describes a generalized process, not every individual may have the same experience. Emerging professionals with cultural identities that have been historically stigmatized may also need to go through a process of “redefinition” in their professional identity development as Slay and Smith (2011) found in a narrative study of African American journalists. As we continue to explore narrative inquiry as a field it is imperative to recognize what narratives are not present or represented. Rather than wait to release this section until we have the entirety of studies we wish to include here, we have chosen to share this living document as it develops from its inception and provide a continual invitation to you to contribute to it. We hope this resource can serve as a form of storying and interacting for all contributors and readers. We offer this beginning as an example of a possible collective unfolding of our becoming together.

References

Andersen, T. (1995). Reflecting processes: Acts of informing and forming. In S. Friedman (ed), The Reflecting Team in Action: Collaborative practice in family therapy (pp.11-37). New York: Guilford.

Annarino, P., & Hall, C. M. (2013). It takes professional community: A Case Study of Interpreter Professional Development in the Pac Rim. RID VIEWS. Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. Alexandria: Virginia.

Balatti, J., Haase, M., Henderson, L., & Knight, C. (n.d.). Developing teacher professional identity through online learning: A social capital perspective. James Cook University. Retrieved from: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/16476/1/Professional_identity_Balatti_1-4-11.pdf

Ball, C. (2007). The history of American Sign Language interpreting education. (Doctoral dissertation), Available from ProQuest Information and Learning Company. (3258295).

Brown, B. (2010). The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You’re Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You Are. Hazelden Publishing. ISBN-10: 9781592858491

Clandinin, J. (2016). Engaging in Narrative Inquiry. eBook Published 16 June 2016. Imprint Routledge: New York. DOI: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315429618. ISBN: 9781315429601

Connelly, F.D and Clandinin, D.J. (eds). (1999). Shaping a Professional Identity. Stories of Educational Practice. New York: Teachers College Press.

Dall’Alba, G. (2009). Learning professional ways of being: Ambiguities of becoming. Educational Philosophy and Theory, Vol. 41, No. 1. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-5812.2008.00475.x

Damasio, A. R. (1999). The feeling of what happens: Body and emotion in the making of consciousness. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company.

Dulwich Centre. (n.d.), ‘Storying professional identity’ Retrieved from: https://dulwichcentre.com.au/articles-about-narrative-therapy/storying-professional-identity/

Falk, I., & Balatti, J. (2003). Role of identity in VET learning. In J. Searle, I. Yashin-Shaw & D. Roebuck (Eds.), Enriching learning cultures: Proceedings of the 11th Annual International Conference on Post-compulsory Education and Training: Vol. 1 (pp. 179-186). Brisbane: Australian Academic Press.

Gibson, D. M., Dollarhide, C. T., & Moss, J. M. (2010). Professional identity development: A grounded theory of transformational tasks of new counselors. Counselor Education & Supervision, 50, 21-38.

Hamilton, H., & McAlpine, A. (2019). Internal Cartography: Our Professional Identity Journeys. Maroney, E., Smith, A., Hewlett, S., Trine, E., & Darden, V., Eds. (2019). Integrated and open interpreter education: The open educational resource reader and workbook for interpreters. Western Oregon University Digital Commons.

Harwood, N. (2017). Exploring professional identity: a study of American Sign Language/English interpreters (Master’s thesis). Western Oregon University, Monmouth, Oregon. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses/37

Hunt, D. (2015). “The Work is You”: Professional Identity Development of Second-Language-Learner American Sign Language–English Interpreters. [Doctoral dissertation]. Gallaudet University, Washington, DC, USA

Slay, H. S., & Smith, D. A. (2011). Professional identity construction: Using narrative to understand the negotiation of professional and stigmatized cultural identities. Human Relations, Volume: 64 issue: 1, page(s): 85-107. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726710384290

Van Manen, M. (1990). Researching lived experience: Human science for an action sensitive pedagogy. London, Ontario, Canada: State University of New York Press.

Winslade, J., Crocket, K., Monk, G. & Drewery, W. (2000). ‘The storying of professional development.’ In G. McAuliffe & K. Eriksen (eds), Preparing Counsellors and Therapists: Creating constructivist and developmental programs (pp.99-113). Virginia Beach, VA: Association for Counsellor Education and Supervision.

Witter-Merithew, A., & Johnson, L. J. (2005). Toward competent practice: Conversations with stakeholders. Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, Incorporated.