Interpreting English Grammar Classes: Theories, Tips, & Tools

Theories, Tips, & Tools

Amelia Bowdell, MA, MA, NIC

Could placing Deaf students in English Language Learner (ELL) grammar classes with interpreters increase their success at obtaining bilingualism? These classes are also referred to as English as a Second Language (ESL), English for Academic Purposes (EAP), or English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classes. In this chapter, strategies will be explored that will look at common linguistic vocabulary and concepts when discussing English grammar. Participants will engage in activities that explore and brainstorm interpretations of grammar concepts. This resource is designed to give interpreters and interpreting students an introduction to relevant theories, tools, and tips to be more effective when interpreting in a grammar class.

Keywords: Interpreting, English Grammar, English Language Learner, Second Language Acquisition, Verb Tense

Background

Grammar provides the path by which language walks and with which we engage with one another. Grammar is part of English instruction at many points in a person’s educational journey. Most notably, grammar is discussed in English and English Language Learner (ELL) classrooms. Being that most people have experienced being in an English classroom, this chapter will focus on the latter common setting for grammar discussion. English grammar topics are often discussed in the context of formal instruction, such as K-12 or higher education. The purpose of this chapter is to provide relevant theories, examples of context when English grammar topics would arise, tools for preparation, and tips for interpreting jargon-heavy grammar concepts.

There are multiple definitions for the English Language Learner (ELL). According to the National Center for Educational Statistics (n.d.), an ELL is defined as an individual whose first language is a language other than English, was not born in the United States, grew up in an area where English is not the main language used or exposed to, and/or is an American Indian or Alaska Native where another language had a significant impact on the individual’s level of English language proficiency. Deaf and hard of hearing international students or those who have immigrated to the United States could qualify under this definition of ELL. According to the Gallaudet Research Institute, under No Child Left Behind Act, 23% of Deaf and hard of hearing K-12 students in the United States are categorized as ELLs because they have a first language that is neither English nor American Sign Language (ASL). According to an article written in the peer-reviewed journal known as “Council for Exceptional Children,” English Language Learner (ELL) is more broadly defined as a diverse group with a variety of first languages, cultures, ethnicities, countries of origin, language proficiencies, socioeconomic status, educational experiences, and time in the United States; it is important to note that this can include people who are born in [or outside] the United States (Sullivan, 2011). This second definition could potentially include all Deaf and hard of hearing students whose first language is not English and who are not currently fluent in English.

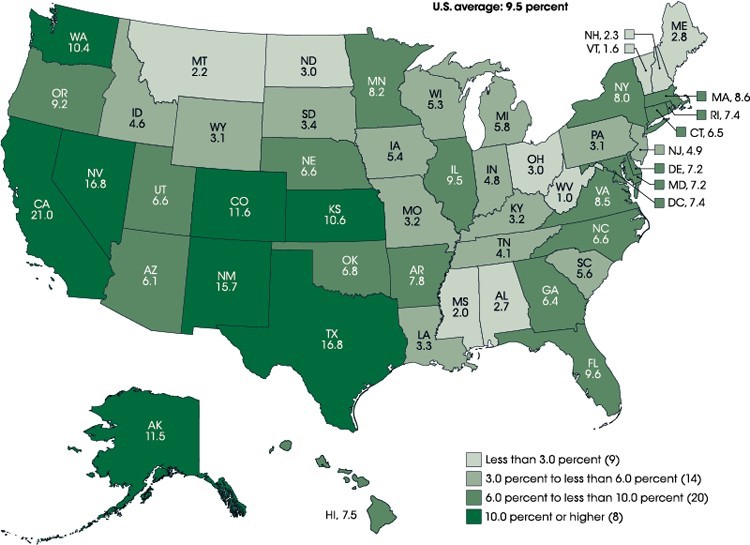

According to the fall 2015 data from the National Center for Educational Statistics that was published in 2018, the percentage of public K-12 United States students who were identified as ELL in the study was 9.5% of 4.8 million students. In the same study, approximately 14.7% of the total ELL population in the United States or 713,000 ELL students were receiving services through the Americans with Disabilities Act; this can include deaf/Deaf students who receive services and/or have an Individualized Education Plan (IEP) (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2018). According to Magrath (2016), many Deaf people face similar difficulties to other ELL students in becoming fluent in English. For example, for some Deaf students, their first language is American Sign Language, which is unique and separate from English and has its own syntax and grammar (Magrath, 2016; National Association of the Deaf, 2019). Learning a new language can be difficult for any student. Knowing that Deaf students can be placed in ELL classrooms is important for interpreters who are or plan to work with Deaf and hard of hearing students because students are in ELL programs to help improve their English proficiency with regard to reading, writing, and grammar. Refer to Figure 1 to see the total percentage of students, including Deaf students, that are identified as ELL’s within each state.

Figure 1. English Language Learners in Public Schools, by state Fall: 2015.

Note: Figure 1. English Language Learners in Public Schools, by state Fall: 2015. Reprinted from “English language learners in public schools,” Retrieved December 2018 from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgf.asp) Copyright 2018 by National Center for Educational Statistics. Reprinted with permission.

ELL programs in the K-12 or college/university settings can be referred to in the literature by a number of other terms such as English as a Second Language (ESL), English Learner (EL), or English for Academic Purposes (EAP). At the community college, college, and university setting, how one is tested for ELL placement varies from one institution to another, such as if a student is an international student or self-identifies that English is not their first language on the college application, the student is then directed to take the ELL Placement Test or Test of English as a Foreign Language (TOFL) instead of the traditional English Placement Test (Arizona Western College, 2019). If the student takes the ELL placement test and the results show they are fluent in English and do not need ELL coursework, then they are encouraged to take the traditional English Placement Test (Arizona Western College, 2019).

Being in an ELL program is not a negative proposition; actually, it presents several opportunities to its participants (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2018). “Participation in these types of programs can improve students’ English language proficiency, which in turn has been associated with improved educational outcomes” (National Center for Educational Statistics, 2018, para. 1). Many ELL programs focus on various skills including but not limited to English reading, writing, and grammar skills (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008).

The goal of an ELL program is for the students to become bilingual (National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum, 2011). In order for a person to be considered bilingual, the individual must have both Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) in two languages (National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum, 2011). Cummins labeled the terms BICS and CALP in 1979 (National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum, 2011).

Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) “describes the development of conversational fluency” (National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum, 2011, para. 17). BICS includes informal and conversational registers of social and conversational language (Bilash, 2011). While a student is learning BICS, they can gradually begin to learn Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP); however, a majority of CALP is learned predominantly after the student learns BICS. The concept of CALP is the development of “language in decontextualized academic situations” (National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum, 2011, para. 17). Usage of CALP requires understanding and applying nuances within the language (Bilash, 2011). Examples of CALP include scholarly sources and textbooks.

Trained ELL instructors use Second Language Acquisition (SLA) methodologies, pedagogies, and techniques to empower students to utilize the knowledge in and of their first language and any other previous language to learn a new language, in this case, English. According to the National Council of Teachers of English (2008), instructors should “position native languages and home environments as resources” or positive and respected tools that can help students learn English (pp.5).

“The way you learned your first language is fundamentally different from the way you learn any additional language” after the age of three (Baker, 2006 & Morehouse, 2017, para. 54). Second Language Acquisition (SLA) is the process of learning one’s second language, third, fourth, or any subsequent language after the age of three (Baker, 2006; Bowdell, 2018). Second Language Acquisition theory supports a variety of philosophies including but not limited to an educational philosophy known as Bilingual-Bicultural education as a way to achieve bilingualism (Baker, 2006). Second Language Acquisition and in turn Bilingual-Bicultural education supports the concept of using one’s knowledge in their first language(s) to learn any subsequent language(s) (Baker, 2006; Bowdell, 2018; Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, 2019). Bilingual-Bicultural education applies to Deaf and hard-of-hearing students as they are being taught language skills in ASL, which can provide the vehicle to learn or improve English skills (Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center, 2019).

Extensive research has been done in the field of Second Language Acquisition (SLA) (National Association for Language Development, 2011). The Center for Applied Linguistics (n.d.) defines Second language acquisition (SLA) research as “the study of how people learn to communicate in a language other than their native language” (para. 2). The landmark research within the field of SLA includes: Behaviorist Learning Theory by Skinner in 1950s versus Mentalist Language Acquisition Theory by Chomsky in the 1960s, Significance of Learners’ Errors by Corder in 1967, ‘Interlanguage’ by Selinker in 1972, Acculturation Model by Schumann in 1978, Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) and Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) by Cummins 1979, The Five Second Language Theories (also known as Input Hypothesis) by Krashen in the 1970s and 1980s, Learner Competence by White in 1980s, ‘Interlanguage’ as a Stylist Continuum by Tarone in 1983, Accommodation Theory by Giles in 1984, Universal Grammar by Chomsky in 1985, Social Identity and Investment in Second Language Learning by Peirce in 1995, Universal Grammar and Multi-Competence by Chomsky in 2007, and Error Analysis by Richards in 2015 (Bowdell, 2018; Ellis, 2008).

The English Language Learner (ELL) classroom setting

English Language Learner classrooms exist in continuing education, K-12, and higher education (such as community college, college, and university) settings (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008). Regardless of the setting, ELL instructors use various techniques in the classroom to support their students learning (Colorín Colorado, 2019). For example, an ELL instructor will avoid using idioms, slang, and contractions (for lower level ELL classes), and the instructor will use lots of visuals in order to explain new concepts (Colorín Colorado, 2019).

Students in ELL classrooms do not only learn English vocabulary (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008). According to the National Council of Teachers of English (2008, p. 4) Students need to learn forms and structures of academic language. They need to understand the relationship between forms and meaning in written language, and they need opportunities to express complex meanings, even when their English language proficiency is limited.

In addition, the instructor can use a lot of highly contextualized grammar and jargon in order to teach grammar rules that are applicable to what the students are learning (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008).

Godfrey (2010) suggested that most students in Interpreter Education Programs’ (IEP) first language is English and they are learning ASL as their second or subsequent language. These IEP students then become the next generation of ASL/English interpreters (Godfrey, 2110). A study done in 2005 by Da ̨browska and Street found that some elements of English grammar including comprehension of passive sentence structure had not been mastered by some native speakers. Upon further examination the data of those who have not attended graduate school or higher, overall the non-native English user group performed better than the native English user group on the same grammar related tasks (Da ̨browska & Street, 2005). Anecdotally, for those people whose first language is English, many of them can read most sentences in English and recognize if it is grammatically correct or not; however, at times if an ELL student asks them why the original sentence was not correct and why the now edited sentence is correct they are unable to explain in detail why this is the case (see Table 1).

Table 1

Incorrect vs. Correct Sentence Example

| Original Passive Sentence: The child was having fright from the bug. | Incorrect |

| Edited Passive Sentence: The child was frightened by the bug. | Correct |

Da ̨browska and Street suggested that the difference in passive sentence comprehension success rate “depends to some extent on metalinguistic skills, which may be enhanced by explicit L2 [ELL] instruction” (2005, p. 605). In an ELL classroom, many instructors spend additional time discussing grammar concepts, compared to a traditional American English classroom (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008). Therefore, that interpreters and/or interpreting students need to learn explicit jargon and techniques for how to interpret English grammar classes is reasonable.

Preparing for the assignment

In preparing for the assignment, the more information interpreters and interpreting students know the better (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 1997 & 2005). According to Dean and Pollard (2013), “all the preparations one does for an assignment… constitute as pre-assignment controls,” which includes the effort to build upon one’s knowledge of the topic in advance (p.19). Controls are how the interpreters and/or interpreting students decide to interact and respond to the particular demands of an interpreting assignment (Dean & Pollard, 2013). Examples that relate to preparing for an ELL interpreting assessment would include knowing the:

- Date, time, and location of assignment

- ELL course level and grade level (if applicable)

- Applicable demographics of the students

- Languages that the various students know

- Language of instruction

- Textbook and other resources used

- The course and unit learning objectives

- Grammar sections the instructor plans to cover (if applicable)

- Grammar related vocabulary that will be discussed and its respective definitions

- Grammar related formulas

- Grammar related rules and exceptions

- What information students are already expected to know by this point

- Review the ASL signs for the various ‘word classes.’

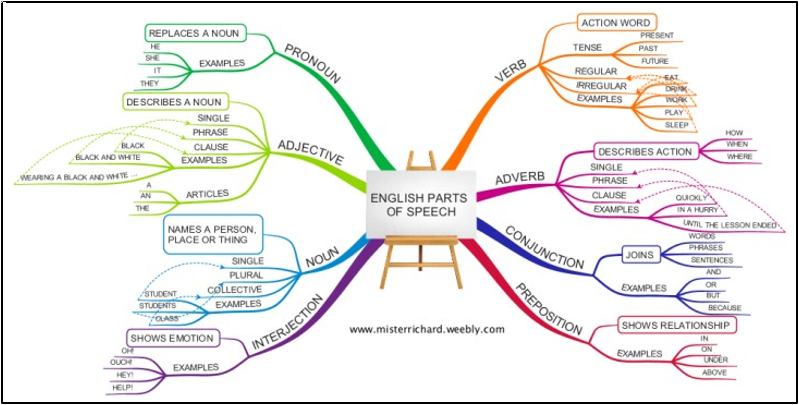

The term ‘word classes’ refers to the seven to eight major parts that are in all signed and spoken languages; these parts are adjective, adverb, conjunction, interjection, noun, pronoun, and verb (Word classes, 2019). Refer to Figure 1 for definitions and examples of each of the ‘word classes.’ The interpreters and/or interpreting students should understand each of these ‘word classes’ jargon, be able to give examples, and know the signs for each because these terms will be used in this setting quite often (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2010).

Figure. 2

Word Classes

Figure 2. From “Learning English: Grammar” by Richard, M. (n.d.). (http://misterrichard.weebly.com/grammar.html). Reprinted with permission.

There is a lot of grammar-related jargon that is used readily in the classroom (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008). The interpreters and interpreting students should get a copy of the class textbook and review the grammar concepts that the instructor plans on teaching. If getting a copy of the textbook is not possible, the interpreter should get a copy of an ELL grammar textbook that has the twelve tenses, or they could search for the specific grammar topic online.

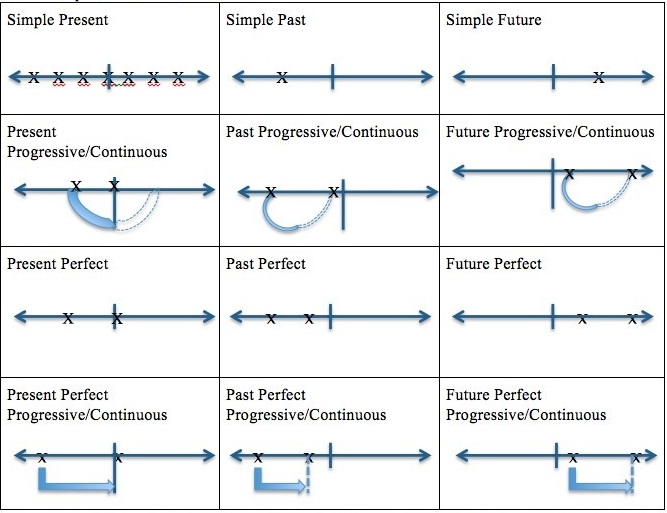

When reviewing grammar concepts, chapters are usually grouped by English tense (Lester, 2008). Tense is indicated in ASL and English differently (Jacobs, 1996). In English, the verb tense indicates when the action is occurring, occurred, started, and ended; therefore in English one modifies the verb to indicate tense (Lester, 2008). There are twelve verb tenses in English (See Table 2 and 3) (Azar & Hagen, 2009). Most verbs in English can take six different basic forms which include: base, infinitive, present, past, present participle, and past participle (Lester, 2008). Refer to Appendix A for a fillable form for pre-assignment controls.

Table 2

Pictorial representation of verb tenses

Note. Adapted from Understanding and using English grammar 4th ed with answer key (p.100) by B. Azar & S. Hagen, 2009, New York, NY: Pearson. Copyright 2009.

Table 3

12 English Verb Tenses

| Verb Tense | Example | Form (Grammar formula) |

| Simple Present | I bake cake everyday.

Robin bakes cake everyday. |

Subject + verb to be + base verb 3rd person singular subject + verb-s |

| Simple Past | Robin baked a cake. | Subject + base verb-ed |

| Simple Future | Robin will bake a cake tomorrow.

Robin is going to bake a cake tomorrow. |

Subject + “will” + base verb

Subject + verb to be + “going to” + base verb |

| Present Progressive/Continuous | Robin is baking right now. | Subject + present form of verb to be + verb+-ing |

| Past Progressive/Continuous | Robin was baking when we arrived. | Subject + past form of verb to be + verb+-ing |

| Future Progressive/Continuous | Robin will be baking when we arrive.

Robin is going to be baking when we arrive. |

Subject + “will” + verb to be + verb+- ing

Subject + “is going to” + verb to be + verb+-ing |

| Present Perfect | I have already baked. Robin has already baked. | Subject + “have” + past participle

3rd person singular subject + “has” + past participle |

| Past Perfect | Robin had already baked when her friend arrived. | Subject + “had” + past participle |

| Future Perfect | Robin will already have baked when her friend arrives. | Subject + “will” + past participle |

| Present Perfect Progressive/Continuous | I have been baking for three hours.

Robin has been baking for three hours. |

Subject + “have been” + verb+-ing

3rd person singular subject + “has been” + verb+-ing |

| Past Perfect Progressive/Continuous | Robin had been baking for three hours before her friend arrived. | Subject + “had been” + verb+-ing |

| Future Perfect Progressive/Continuous | Robin will have been baking for three hours by the time her friend arrives. | Subject + “will have been” + verb+- ing |

Within the specific verb tense, interpreters and/or interpreting students should focus their preparation on knowing the following about the verb tense:Note. Adapted from Understanding and using English grammar 4th ed with answer key (p.101) by B. Azar & S. Hagen, 2009, New York, NY: Pearson. Copyright 2009.

- Name of verb tense

- When is this verb tense used

- Verb tense grammatical formula

- Rules for applying the verb tense correctly

- Exceptions of the rules.

This is also known as name, form, and meaning of the verb tense (Azar & Hagen, 2009). ELL students will learn a given verb tense by first learning when to use it, next they will memorize the various grammar formulas for the new verb tense, and they will simultaneously learn the grammar rules and exceptions that apply to the verb tense (National Council of Teachers of English, 2008). An example of what to study in preparation for a Simple Present tense grammar lesson can be seen in Table 4. A blank fillable version of Table 4 is available in Appendix A. To practice the grammar concepts, the interpreters and interpreting students can refer to Appendix C and D.

Table 4

Simple Present Tense

| Name | Form (Grammar Formula) | Meaning | Example |

| Verb Tense Name | Simple Present Tense | ||

| Affirmative Statement | Subject + verb to be + base verb | Used to show habitual actions or states, general facts, or conditions that are now true | I bake cake every day. |

| Negative Statement | Subject + verb to be + negative + base verb | Used to show habitual actions or states, general facts, or conditions that are not true | I am not a bear. |

| Affirmative Statement with 3rd person singular subjects | 3rd person singular subject + verb+s

*3rd person singular subjects: He, she, it, and name |

Used to show habitual actions or states, general facts, or conditions that are now true | Robin bakes cake every day. |

| Yes/No Questions | Verb to be + subject | Used to ask yes/no questions about habitual actions or states, general facts, or conditions that are now true. | Are you a baker? |

| Wh-Questions | Wh-word + subject

+ base verb |

Used to ask wh-questions about habitual actions or states, general facts, or conditions that are now true. | Will you bake a cake? |

Note. Adapted from Understanding and using English grammar 4th ed with answer key (p.102) by B. Azar & S. Hagen, 2009, New York, NY: Pearson. Copyright 2009.

Tips and tools for interpreting grammar classes

As an interpreter or interpreting student, it is important to match the language of the Deaf or hard-of-hearing consumer(s) (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2005, 2010). For example, if the Deaf or hard-of-hearing consumer uses ASL, then the interpreter should follow suit (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2005, 2010). On the other hand, if the Deaf or hard-of-hearing consumer uses Pidgin Signed English /contact sign, Signing Exact English, Cued-Speech, or another sign system, then the interpreter should do their best to match the consumer. This includes when the instructor is explaining a specific word order for a given tense (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2005, 2010). Some interpreters and/or interpreting students may be tempted to interpret into a form of Manually Coded English for jargon-heavy grammar concepts courses. If the consumer uses a form of contact sign or Manually Coded English such as Signing Exact English, than this technique may be effective. However, if the Deaf consumer utilizes mostly ASL, it is necessary to make the English verb tense concept in ASL and as visual as possible (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2005, 2010). This requires that interpreters and/or interpreting students have a firm grasp of ASL grammar rules and word order. The interpreters or interpreting students could then physically move the parts of the sentence around visually using classifiers to clearly demonstrate the new English verb tense word order and how it differs from ASL word order. If the consumer’s language preference is known in advance, the interpreters and/or interpreting students could anticipate this and could prepare by practicing with sentences that have a similar form to the grammar structure that will be taught. They could begin by explaining the concept of the English sentence in ASL. Next, the interpreter could visually and physically move the parts of the sentence from ASL into English word order, using classifiers. Example sentences of Simple Present tense form can be found in Table 4.

In looking at Table 2, one can see how each verb tense can be represented in a pictorial manner (Azar & Hagen, 2009). Since ASL lends itself to easily expressing visual concepts, one could use classifiers to create and explain the verb tense timeline visually (Jacobs, 1996). Interpreters and/or interpreting students could practice interpreting each of the tense timelines outlined in Table 2 (Azar & Hagen, 2009). As the course continues, the interpreter could refer back and add to the original verb tense timeline that was established as new verb tenses are introduced by the instructor. In this way, students could see how the various English verb tense timelines overlap one another, which provides context for learning and building upon what the student knows (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2010)

In looking at Table 3 and Table 4, one can see that each English tense can be represented in a grammar formula (Azar & Hagen, 2009). Interpreters and/or interpreting students could practice interpreting each of the grammar formulas outlined in Table 3 and Table 4 (Azar & Hagen, 2009). In math and chemistry courses, interpreters and/or interpreting students interpret formulas; the same technique can be used to represent grammar formulas. In a classroom setting, the teacher often writes the grammar formula from left to right on the board behind the interpreter. If the interpreter and/or interpreting student is sitting in the front of the room with the board at their back, they could sign the grammar formula so it aligns with what the student is seeing on the board (behind the interpreter). This could provide continuity for the student learning the new English grammar formula. This is another reason why preparation including learning the grammar formulas and rules prior to the assignment is so important for the interpreter (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2005, 2010).

Practicing specific interpreting skills prior to an assignment should be part of an interpreter’s preparation (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2005, 2010). Interpreters and/or interpreting students could ask if they could observe an ELL classroom prior to their assignment. This would allow them to see how Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theories are applied in an ELL classroom. If this is not possible, an interpreter could watch ELL instructional videos online. One current YouTube channel that is similar to how an in-person ELL instructor teaches using SLA is known as JenniferESL (Lebedev, n.d.). JenniferESL’s YouTube channel is published and aligned with the popular ELL grammar textbook series titled Focus on Grammar (Lebedev, n.d.; Schoenberg, Maurer, Fuchs, Bonner, Westheimer, 2016). The interpreter could practice putting all of the skills to active use by playing a video and mock interpreting it to a Deaf consumer, mentor, fellow student, or recording it to view later for reflection.

Use Appendix A and B to write out pre-assignment controls. Utilize Appendix C and D to practice the various grammar tenses and rules the interpreters and/or interpreting students are learning. Interpreting ELL classes in the K-12 and college/university settings can be difficult; however, building knowledge, preparation, and practice can have a positive impact on the interpreting assignment.

Further Research

This chapter begins to scratch the surface of the complex task of interpreting jargon-heavy English grammar coursework. This chapter could be used as a discussion jumping off point for collaboration between interpreters and interpreting students and all consumers about how to best approach this unique and complex interpreting setting. It is the opinion of this author that a standardized ELL definition be thoroughly researched by all parties to increase success rates for Deaf students in obtaining bilingualism. Further research needs to be done on the success rate of evidenced-based collaboration techniques between all consumers for Deaf ELL students in grammar courses

About the Author

Amelia Bowdell currently works full-time as a Professor and ASL interpreter. She earned her bachelor’s degree in Signed Language Studies: ASL Interpreting, and her first master’s degree related to ESL teaching Second Language Acquisition, pedagogy, and methodology known as Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) from Madonna University. Amelia completed a second master’s degree in Interpreting Studies: Teaching Interpreting from Western Oregon University. She successfully defended and published her master’s thesis related to developing bilingualism in ASL and English using BICS, CALP, and Second Language Acquisition. Amelia has been interpreting since 2005 and has a National Interpreter Certificate (NIC). She has a vast array of interpreting experiences as a staff, agency, and freelance interpreter in a variety of settings including: higher education, K-12, medical, mental health, theatre, business, dance, and various other settings. Amelia has been teaching at the college level for more than ten years. She has presented at multiple state and national conferences on various topics. Her research interests include but are not limited to bilingualism, Second Language Acquisition, ASL linguistics, assessment, and meaning transfer for interpreters. On a personal note, she enjoys spending time with her wonderfully supportive husband Jeffrey and their two loving dogs.

Acknowledgments:

I would like to express my appreciation to Elisa Maroney, Amanda Smith, Sarah Hewlett, Erin Trine, and Vicki Darden for their valuable time and editing suggestions during this publication process. I would also especially like to thank my family for their continued support of my passion for research and knowledge. They are always willing to explore and discuss various research topics together. I am forever grateful to my husband and best friend, Jeffrey Bowdell, for his unwavering love, support, and patience as I venture on this journey.

References

Arizona Western College (2019). Placement Testing. Retrieved from https://www.azwestern.edu/enrollment/testing-services/accuplacer-testing

Azar, B. & Hagen, S. (2009). Understanding and using English grammar 4th ed with answer key. White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Baker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism (4th ed.). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters

Bilash, O. (2011). BICS/CALP: Basic interpersonal communicative skills vs. cognitive academic language proficiency. Retrieved from https://sites.educ.ualberta.ca/staff/olenka.bilash/Best%20of%20Bilash/bics%20calp.html

Bowdell, A. (2018). Developing bilingualism in interpreting students (Masters thesis). Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses/44/

Center for Applied Linguistics. (n.d.). Second Language Acquisition. Retrieved on March 1, 2019 from http://www.cal.org/caela/esl_resources/collections/SLA.html

Colorín Colorado. (2019). Classroom strategies and tools. Retrieved from http://www.colorincolorado.org/teaching-ells/ell-strategies-best-practices/classroom- strategies-and-tools

Da ̨browska, E. & Street, J. (2005). Individual differences in language attainment: Comprehension of passive sentences by native and non-native English speakers. Language Sciences, 28(2006), 604-615.

Dean, R. & Pollard, R. (2013). The Demand Control Schema: Interpreting as a practice profession. North Charleston, SC: Create Space Independent Publishing Platform

Ellis, R. (2008). The study of second language acquisition (2nd ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Gallaudet Research Institute. (2011, April). Regional and national summary report of data from the 2009-10 Annual Survey of Deaf and Hard of Hearing Children and Youth. Washington, DC: Gallaudet Research Institute, Gallaudet University.

Godfrey, L. (2010). Characteristics of effective interpreter education programs in the United States (Doctoral dissertation). University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, Chattanooga, Tennessee. Retrieved from http://cit-asl.org/IJIE/2011_Vol3/PDF/8-Godfrey.pdf

Jacobs, R. (1996). Just how hard is it to learn ASL: The case for ASL as a truly foreign language. In C. Lucas (Ed.), Multicultural aspects of sociolinguistics in Deaf communities (pp. 183- 216). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press

Laurent Clerc National Deaf Education Center. (2019). American Sign Language/English bilingual and early education. Retrieved from http://www.colorincolorado.org/article/american-sign-languageenglish-bilingual-and- early-childhood-education

Lebedev, J. (n.d.). Home. [JenniferESL]. Retrieved on March 1, 2019 from https://www.youtube.com/user/JenniferESL/featured

Lester, M. (2008). McGraw-Hill’s essential ESL grammar: A handbook for intermediate and advanced ESL students. New York, NY: McGraw Hill

Magrath, D. (2016). The need for ESL instruction for Deaf students. Retrieved from http://exclusive.multibriefs.com/content/the-need-for-esl-instruction-for-deaf- students/education

Morehouse, K. (2017). Lingua Core UG: What are L1 and L2 in Language Learning. Retrieved from https://www.linguacore.com/blog/l1-l2-language-learning/

National Association for Language Development in the Curriculum. (2011). Bilingualism and second language acquisition. Retrieved from https://www.naldic.org.uk/eal-initial- teacher-education/resources/ite-archive-bilingualism/

National Association of the Deaf. (2019). What is American Sign Language? Retrieved from https://www.nad.org/resources/american-sign-language/what-is-american-sign-language/

National Center for Educational Statistics. (April, 2018). English Language Learners in public schools. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgf.asp

National Center for Educational Statistics. (April, 2018). English Language Learners in Public Schools: Figure 1 Percentage of public school students who were English language learners, by state: Fall 2015. Retrieved from: https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator_cgf.asp

National Center for Educational Statistics. (n.d.). Glossary. Retrieved on December 20, 2018 from https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/glossary.asp#ell

National Council of Teachers of English (2008). English language learners: A policy research brief. Retrieved from http://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/PolicyResearch/ELLResearchBrief.pd f

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (April, 2017). American Sign Language. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/american-sign- language

National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (December, 2016). Quick statistics about hearing. Retrieved from https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/statistics/quick-statistics-hearing

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (1997). Professional Sign Language Interpreter. In Standard practice papers. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3DKvZMflFLdeHZsdXZiN3EyS0U/view

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (2005). Code of professional conduct. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-_HBAap35D1R1MwYk9hTUpuc3M/view

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (2010). An Overview of K-12 Educational Interpreting. In Standard practice papers. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B3DKvZMflFLdcFE2N25NM1NkaGs/view

Richard, M. (n.d). Learning English: Grammar. Retrieved on March 1, 2019 from http://misterrichard.weebly.com/grammar.html

Schoenberg, I., Maurer, J., Fuchs, M., Bonner, M., & Westheimer, M. (2016). Textbook Series: Focus on Grammar. New York, NY: Pearson Education.

Sullivan, A. (2011). Disproportionality in Special Education Identification and Placement of English Language Learners. Council for Exceptional Children, 77(3), 317-334.

Verb tenses (2019). Oxford Living Dictionaries. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/grammar/verb-tenses

Word classes (2019). Oxford Living Dictionaries. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/grammar/word-classes-or-parts-of-speech

Appendix A

Pre-Assignment Control: Verb tense: Fillable form

| Name | Form

(Grammar Formula) |

Meaning | Example |

| Verb Tense Name | |||

| Affirmative Statement | |||

| Negative Statement | |||

| Affirmative Statement with 3rd person singular subjects |

|

||

| Yes/No Questions |

|

||

| Wh-Questions |

|

(Azar & Hagen, 2009).

Appendix B

Pre-Assignment Control: Collection of Relevant Assignment Information

- ELL Level:

- Applicable demographics: (grade level, approximate age, languages known by the students, and other relevant information)

- Language of instruction:

- Name of the textbook(s):

- Do you have access to it? Yes or No

- If not, think of other online resources you can access to gather information:

- Any other handouts or online resources for the course:

- Course & unit learning objectives:

- Grammar sections to be covered in this lesson:

- Grammar vocab and definitions:

Grammar related rules & exceptions:

- Other Non-grammar related vocab:

- If one or more of the non-grammar vocabulary words are verbs, fill in the table below.

| Base | Infinitive | Present | Past | Present Participle | Past Participle |

| Be | To be | Am, Is, Are | Was, Were | Being | Been |

| See | To see | See, Sees | Saw | Seeing | Seen |

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

|||||

|

|

- Deaf consumer’s language preference (if known):

- Look at Table 2. Practice how to visually represent the applicable verb tense in the consumer’s language preference. Use classifiers if appropriate. Use the space below to write down any notes you would like.

- Looking at Appendix B, practice how to visually represent the applicable grammar formulas in the Deaf consumer’s language preference. Practice signing the grammar formula start on the right and moving toward the left and vice versa.

- Contact the point-of-contact for the interpreting assignment, and ask if an observation can be done in advance.

- Are you able to observe the classroom in advance? Yes or No

- Date, time and location of observation:

- Use online videos to simulate an ELL classroom lecture.

- Record yourself interpreting the mock assignment.

- Watch the video and record your initial reaction to it.

- Take a break.

- Rewatch your video.

- Post-Reaction: What were you proud of? What pre-assignment controls do you feel helped you? What other pre-assignment controls would you employ for similar future assignments?

Appendix C

Note. Appendix C & D has been adapted from Pre-Test by S. Lund, 2019, (Unpublished Handout). Arizona Western College, Yuma, AZ. Adapted with permission.

Instructions

Read sentences 1-16. Determine if each of the sentences is correct or incorrect. If the sentence is correct, circle correct. If the sentence is incorrect, fix it. For a challenge, explain the rationale for the correction. Explaining why the specific correction was needed is good practice because these are the types of questions a student will ask in a grammar class. An answer key for this activity can be found in Appendix D.

- Let’s keep this a secret between you and I.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- Her and Mike eat out often.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- By the time I had arrived, the teacher had already left.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- I could of had a Pepsi.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- I wish I had went with you.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- Me and you need to talk.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- She don’t need nobody to tell her what to do.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- We have less students this year than we did last year.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- Spanish is more easy than French.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- I don’t like them cookies.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- Pizza Hut is better then Domino’s.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- John needs a ride because his car is broke.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- This is the best movie I ever saw.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- The teacher gives us alot of homework everyday.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- If I was you, I wouldn’t repeat that.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

- My new car is red, and its interior is leather.

- Circle: Correct or Incorrect

- Rewrite the sentence without errors:

- Explain the rationale for the correction:

Appendix D.

Verb tense: Checking for comprehension: Answer Key

Note. Appendix C & D has been adapted from Pre-Test by S. Lund, 2019, (Unpublished Handout). Arizona Western College, Yuma, AZ. Adapted with permission.

The brief rationales for the corrections are in reference to Standard American English. The rationales provided below all use the same reference of Azar & Hagan, 2009.

- Let’s keep this a secret between you and me I.

- The rationale for correction:

- Use “I” as the subject of a sentence, and “me” as the object.

- The rationale for correction:

- Her She and Mike eat out often.

- The rationale for correction:

- “She” is a subject pronoun and is used before the verb. “Her” is an object pronoun, which means it is used after the verb.

- By the time I had arrived, the teacher had already left. [delete “had”]

- The rationale for correction:

- The portion of the sentence before the comma is a dependent phrase or dependant clause in Simple Past tense. The grammar formula for Simple Past tense is “Subject + base verb-ed.” For more information, refer to Table 2 and 3.

- I could of have had a Pepsi.

- The rationale for correction:

- This sentence needs to be in Present Perfect tense. Present Perfect tense is used when talking about a past action that is continuing into the present. The grammar formula for Present Perfect is “Subject + “have” + past participle.” For more information, refer to Table 2 and 3.

- The rationale for correction:

- I wish I had went gone with you.

- The rationale for correction:

- Incorrect verb form. This is what someone wishes they had done in the past. The hypothetical situation is written in the past and then it is followed up by the Past Perfect tense. The grammar formula for Past Perfect tense is “Subject + “had” + past participle.” For more information, refer to Table 2 and 3.

- The rationale for correction:

- Me and you You and I need to talk.

- The rationale for correction:

- Use “I” as the subject of a sentence, and “me” as the object. You always write yourself last.

- The rationale for correction:

- She don’t doesn’t need nobody anybody to tell her what to do.

- The rationale for correction:

- In English, double negatives are not grammatically correct; however, they are permissible in some other languages.

- The rationale for correction:

- We have less fewer students this year than we did last year.

- The rationale for correction:

- “Students” is a plural count noun, so we need to use the word “fewer.” The word “less” is used with plural noncount nouns.

- The rationale for correction:

- Spanish is more easy easier than French.

- The rationale for correction:

- For comparative adjectives like in the sentence above, you need to add the suffix “-er” to the and of the adjective. In this situation “easy” ends in a “y,” so you drop the “y” and add “ier.”

- The rationale for correction:

- I don’t like them those cookies.

- The rationale for correction:

- “Them” is an object pronoun and “those” is a demonstrative adjective to describe which ones.

- The rationale for correction:

- Pizza Hut is better then than Domino’s.

- The rationale for correction:

- “Then” is commonly used to express a sense of time, what comes next, or what used to be the case. “Than” is used to compare two things or concepts.

- The rationale for correction:

- John needs a ride because his car is broke broken.

- The rationale for correction:

- “Broke” is the Simple Past tense of the base verb “break.” The car broke in the past and it continues to be “broken.”

- The rationale for correction:

- This is the best movie I have ever saw seen.

- The rationale for correction:

- This sentence is in Present Perfect tense. The grammar formula in “Present Perfect” is “Subject + “have” + past participle form of the verb. “Have” needed to be inserted after the subject. “Saw” is Simple Past form of the verb, so it needed to be changed into the past participle form of the verb. For more information, refer to Table 2 and 3.

- The rationale for correction:

- The teacher gives us alot a lot of homework everyday every day.

- The rationale for correction:

- The word “alot” is not a correct English word in Standard American English. The word “everyday” is an adjective that describes the noun in the sentence. “Every day” is synonymous with the phrase each day.

- The rationale for correction:

- If I was were you, I wouldn’t repeat that.

- The rationale for correction:

- In Simple Past tense the phrase “I was…” would be correct. However, this specific sentence is a hypothetical situation sentence with the purpose to give advice to another person. For hypothetical sentences about giving advice the phrase “If I were you…” is used.

- The rationale for correction:

- My new car is red, and its’ its interior is leather.

- The rationale for correction:

- “It’s” is a contraction for “it is” or “it has.” “Its” is the possessive form of “it,” for example if the object owned or belonged to something.

- The rationale for correction:

References

Azar, B. & Hagen, S. (2009). Understanding and using English grammar 4th ed with answer key. White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Lund, S. (2019). Pre-Test (Unpublished Handout). Retitled as “Verb tense: Checking for comprehension.” Arizona Western College, Yuma, AZ.