Orientation to the Interpreted Interaction

Colleen Jones

Abstract

Data has shown that a lack of information for hearing consumers can result in confusion, distraction, and a negative impression of the Deaf consumer (Jones, 2017). This chapter explains the importance of education for consumers that supports their understanding of working with interpreters, which is called orientation to the interpreted interaction or consumer orientation. Readers are encouraged to consider how various approaches to consumer orientation can incorporate elements of the Function, Expectations, and Inclusion (FEI) model, who might be responsible for conducting orientation, when it could take place, and how different options fall on a decision-making spectrum. Activities for students developing their understanding of orientation to the interpreted interaction are included.

Introduction

Interpreters work in a variety of spaces with consumers from all walks of life. In just one week an interpreter might encounter dozens of consumers. Some will have familiarity with working with interpreters, and some will be novices. Regardless of their experience, some consumers will quickly pick up on how to effectively and respectfully communicate with people who use a different language, while others will struggle.

People are not born understanding the function of the interpreter, how to work with interpreters, or how to be inclusive of everyone in the interpreted interaction. Misunderstandings can have negative impacts on consumers, the message, and the interpreter. As will be explained in this chapter, education for consumers—also known as orientation to the interpreted interaction or consumer orientation—is critically important.

What Happens When Orientation is Omitted?

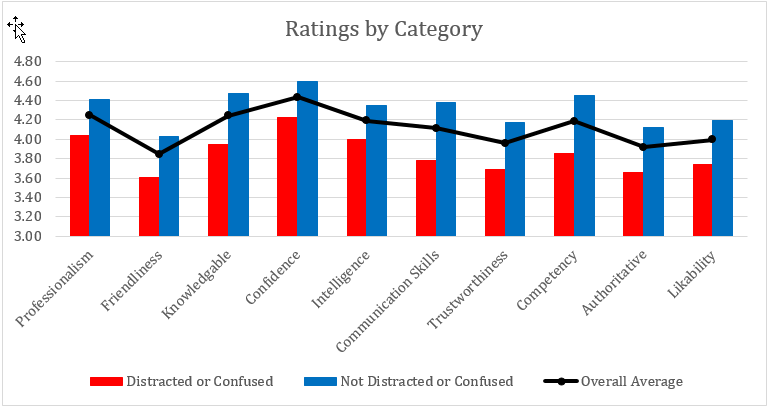

Recent studies have demonstrated the importance of consumer orientation by examining the impact on consumers when orientation is omitted. Jones (2017) conducted a study of 357 hearing North Americans who are not fluent in American Sign Language (ASL). As part of the survey, participants were asked to watch a video of a presentation in ASL while listening to an interpretation of the message in spoken English, and then provide both qualitative and quantitative responses to questions that were intended to gauge their impression of the presenter. The survey did not introduce the presenter or the interpreter and did not include an orientation that would tell participants what to expect. Almost half (44%) of participants’ open-ended responses indicated feelings of confusion or distraction while watching the video (p. 58). Furthermore, those who indicated feelings of confusion or distraction gave the presenter lower-than-average scores in all ten soft skill categories- professionalism, friendliness, knowledgeability, confidence, intelligence, communication skills, trustworthiness, competency, authoritative, and likability (p. 59). Figure 1 shows the average rating in each soft skill category as well as ratings from participants who were confused and/or distracted and ratings from participants who were not confused and/or distracted.

Figure 1: Ratings in each soft skill category

Part of the demographic information collected for this survey included whether participants were familiar with interpreters—participants could indicate that they were very familiar, somewhat familiar, or not at all familiar. Interestingly, responses to this question had little bearing on whether participants indicated confusion or distraction while watching the video—47% of those who were not familiar with interpreters indicated confusion or distraction versus 44% of those who were very familiar with interpreters (Jones, 2017, p. 64). It seems intuitive that consumers who have previous experience working with interpreters would not need consumer orientation, but these results indicate that might not be the case.

These findings are important because they suggest that a lack of orientation can set the interpreter and the consumers up for failure. The data indicate that regardless of how engaging the people are, how insightful the content of the message, or how accurate the interpretation, when consumers are busy trying to figure out what the heck is going on they are less able to engage and attend to the message. In this scenario, everyone involved in the interaction has the potential to be impacted. The hearing consumer may feel confused about the process and has missed out on the content of the message. The Deaf consumer may have picked up on cues that they were not heard and wonder why. The interpreter may feel unsatisfied with their work because they could feel that something was missing but they are not sure what it is.

The hearing consumer’s impression of the Deaf consumer is equally important. The soft skills measured in this study have a direct impact on career success and can make or break whether someone gets a job offer, has access to upward mobility, and experiences success in their workplace. The data suggests that regardless of the Deaf person’s expertise and the interpreter’s skill, a lack of consumer orientation may have a negative impact in all of these areas.

Why do Consumers Need Orientation?

While many aspects of interacting with another person are unchanged by the presence of an interpreter, the experience can still throw consumers for a loop. Consumer orientation is an important topic to consider because research has shown that hearing consumers often misunderstand the interpreter’s job, their relationship with the Deaf person, and how to work with interpreters effectively (Hsieh, 2010; Kredens, 2017; Metzger, 1999).

In one example of this, Leeds (2009, as cited in Llewellyn-Jones & Lee, 2014) surveyed doctors’ clinics in the United Kingdom. In spite of the fact that the clinics who participated in the study all held contracts with an agency that was providing fully qualified interpreters, when asked who was interpreting for their Deaf patients, 54% “thought the person accompanying the patient was a ‘friend’, 15% a ‘carer’, and 8% a ‘social worker’” (p. 43).

While it is often true that the Deaf consumer has more experience working with interpreters than the hearing consumer does, interpreters should keep in mind that there may be gaps in the Deaf consumer’s understanding of how the interpreter will function in any given scenario and how all parties can best work together. Although this chapter is geared toward education for the hearing consumer, many of the principles outlined here could apply to orientation for the Deaf consumer as well.

Why Have Best Practices Not Been Developed?

In spite of the fact that interacting with consumers is an integral part of what interpreters do, very little has been written about this interaction outside of the process of interpreting the message. No standards or best practices have been established for the education of consumers or the interpreter’s part in this. One likely reason for this is that interpreters feel constrained by their ethical codes and the myth of invisibility.

It is commonly understood that when the Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf (RID) was established in 1964, many interpreters had been approaching the work from a paternalistic ‘helper’ or caretaking approach. In response to this, a Code of Ethics was developed, and the inevitable pendulum swing led to interpreters being characterized as “conduits” or “machines” in an attempt to respect the autonomy of Deaf consumers (Witter-Merithew, 1999, p. 2). Even though subsequent models of interpreting have moved away from this impersonal approach to the work, research has shown that interpreters still employ specific techniques in an attempt to appear invisible (Witter-Merithew, Swabey, & Nicodemus, 2011; Hsieh, 2010).

Interpreters’ attempts to remain invisible can be further supported by a conservative interpretation of the current Code of Professional Conduct (Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf, 2005). Tenet 2.5, for example, advises that interpreters “refrain from providing counsel, advice, or personal opinions” (p. 3) and tenet 3.5 says that interpreters should “conduct and present themselves in an unobtrusive manner” (p. 3). Several influential researchers have agreed that a literal reading of these tenets discourages interpreters from interacting with consumers (Dean & Pollard, 2005; Llewellyn-Jones & Lee, 2014; Witter-Merithew et al., 2011).

All of this is not to say that interpreters do not have the best of intentions. There is a fine line between interacting appropriately in order to improve communication access and inserting one’s self to the point of impeding consumers from participating in the interaction themselves. To further complicate things, this line moves dramatically from one scenario to the next and depends upon who the consumers are. For this reason, the models and discussions of consumer orientation in this chapter are meant to allow maximum flexibility. Application will depend on the interpreter’s judgment, the needs and preferences of consumers and other stakeholders, and a myriad of other factors that vary from one assignment to the next.

FEI Model for Consumer Orientation

Effective consumer orientation includes three elements: Function of the interpreter, Expectations for what the interaction will be like, and Inclusion for all parties (FEI). Depending on the setting and the consumer, each element may be touched on briefly or may be expanded upon in more depth. Regardless of whether the orientation to the interpreted interaction takes ten seconds or ten minutes, these three elements can be included.

Function: How will the interpreter function in the context of this interaction?

Examples:

- I am the interpreter for your meeting with John today.

- I will be standing to the side of the stage interpreting your presentation into American Sign Language.

- When you speak, I will listen to what you are saying then interpret it into American Sign Language. When the Deaf person makes a comment, they will sign it in ASL and I will watch what they are saying and then interpret it into English so you can understand them.

- Feel free to speak as you naturally would. If any clarification is needed for the interpreting process or if we need to make adjustments to better facilitate communication I will let you know.

- There are two interpreters today and we will be working as a team. One of us will be interpreting the message and the other will be monitoring for accuracy and ready to support when needed.

Expectations: What can the consumer expect when working with an interpreter? How might this experience differ from a typical monolingual interaction?

Examples:

- You might notice a bit of a pause while I am processing the message and then interpreting it.

- I will be standing a bit behind you so the Deaf person can make eye contact with you and see me at the same time. My voice will be behind you, but the person interacting with you is in front of you.

- The two interpreters will be switching every fifteen to twenty minutes.

Inclusion: What can be done to ensure the interaction is inclusive and satisfactory for everyone?

Examples:

- I can only interpret for one person at a time, so if there is cross-talk or a side conversation, some people will miss out on it because it has not been interpreted. As the chairperson, can you pay attention to turn-taking and make sure people aren’t talking on top of each other?

- Even though my voice will be coming from behind you, go ahead and look at the Deaf person when they are signing to you. It is respectful and you will be able to pick up on their facial expressions and body language.

- Instead of talking to me, go ahead and speak directly to the Deaf person and use first person language. You don’t have to say, “Ask her if she’s going to the meeting,” you can just say, “Are you going to the meeting?”

Who Should Conduct Consumer Orientation?

It is important to recognize that the interpreter is not always the appropriate person to conduct the orientation to the interpreted interaction. Consumer orientation could be conducted by the Deaf consumer, a hearing consumer, a coordinator or agency, an advocate, or a facilitator. The choice of who should conduct the orientation depends on the individuals involved, their relationships with each other, the power dynamics in that particular situation, timing and availability, as well as other factors. This decision requires communication between the interpreter and the stakeholders, and is best supported by a mutual understanding of the importance of consumer orientation.

Consumer Orientation as a Spectrum

When considering how to conduct consumer orientation, it can be helpful to think of how various options fall on a spectrum. This approach to the work is helpful because there are no right or wrong decisions—any part of the spectrum may be appropriate for different situations.

The first spectrum to consider is a level of formality spectrum (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Level of formality spectrum

Informal consumer orientation may be appropriate when the setting is casual, the consumers know each other well, or when a slip-up or misunderstanding will have minimal impact. An example of informal consumer orientation would be a low-key reminder of one or more elements from the FEI model. Formal consumer orientation may be appropriate when the setting is more formal, it is vitally important that everyone is on the same page, or when misunderstandings would have a significant impact on individuals or on the interpreted message. An example of formal consumer orientation would be a written document describing how interpreters will function during a legal trial and that becomes part of the official court record.

The second spectrum is Dean and Pollard’s (2004) liberal-conservative spectrum (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Liberal-conservative spectrum

Dean and Pollard’s demand-control schema explains that control options, which are potential responses to job challenges, can range from liberal (described as “active, creative, or assertive”) to conservative (described as “reserved or cautious”; 2004, p. 3). An example of a liberal approach to consumer orientation would be arriving at a job early and seeking out the hearing consumer in order to conduct a preliminary orientation. An example of a conservative approach would be omitting the pre-assignment orientation and allowing the Deaf consumer to decide whether to address misunderstandings such as the use of third person language.

The third spectrum is Llewellyn-Jones and Lee’s (2013) presentation of self spectrum (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Presentation of self spectrum

Low presentation of self is defined as “behaviors associated with the machine model or ‘invisible’ interpreter, e.g., not interacting with the participants,” while high presentation of self is defined as “presentation of self in ways that are consistent with the situation, e.g., introducing one’s self” (Llewellyn-Jones & Lee, 2013, p. 59). An example of a decision about consumer orientation that aligns with low presentation of self would be waiting to interact with any of the hearing consumers until the Deaf consumer arrives. An example of high presentation of self would be introducing one’s self and having a conversation that includes elements from the FEI model without the Deaf consumer present.

Again, it is important to note that none of these approaches are automatically right or wrong. Use of these various spectrums can help interpreters analyze their decisions and identify opportunities to expand their options.

When Should Consumer Orientation be Conducted?

For many people, it is easy to assume that consumer orientation should take place just before an assignment begins at the time that the interpreter introduces himself or herself. It is worthwhile, however, to consider other options for when effective orientation might occur. Jones (2018) wrote:

Orientation could take place before the interpreter arrives for a face-to-face interaction—perhaps as part of the assignment booking process or as part of an orientation for newly hired employees at a company where interpreters are frequently used. Likewise, interpreters may finish an assignment and decide that the parties could benefit from further explanation before they meet again. There may be times when an interaction needs to be interrupted briefly to make adjustments that will facilitate communication and make the interaction more accessible to one or more participants.

It is also possible that as awareness of the need for consumer orientation grows, individuals or organizations may develop resources that include pertinent information from the FEI model. Interpreters and other stakeholders (i.e., coordinators, consumers, and agencies) may have the option of referring consumers to these resources before and after assignments.

Conclusion

Misunderstandings during interpreted interactions can have a negative impact on consumers, the interpreted message, and interpreters. Education for consumers—also known as orientation to the interpreted interaction or consumer orientation—can support their understanding of what it means to work with an interpreter and how to do so effectively. The FEI (Function, Expectations, Inclusion) model for consumer orientation provides a framework for orientation in any format. In addition to elements from the FEI model, interpreters can consider who might be best suited to conduct orientation in a given setting, when orientation should take place, and where potential options fall on various spectrums. Activities for students considering and practicing consumer orientation can be found in the next section.

Activities

Brainstorm: What are some key phrases that explain the function of the interpreter? What information can be shared with consumers that helps them understand why the interpreter is here and what the interpreter will be doing?

Observe: Observe a working interpreter. Take notes on all of the ways you notice that the interpreted interaction is different from a monolingual interaction. What do you notice that might cause confusion for someone who is not familiar with interpreters and their process?

Consider: Working alone or in a group, choose several potential control options for consumer orientation. List the consequences and resulting demands for each option, then discuss what you notice.

Inquire: Interview one or more working interpreters. Ask what Deaf and hearing consumers can do to make the interpreter’s job easier and to ensure that the interaction is inclusive of all participants. Ask what consumers could do that would make the interpreter’s job more challenging or the interaction less inclusive. Ask what the interpreter does to ensure consumers know what to expect during the interpreting process.

Practice: Using the FEI model and information from the above activities, write out a script for orienting a consumer, then practice introducing yourself and providing this consumer orientation. What information will you share if you have only ten seconds? Thirty seconds? Five minutes?

Come up with a specific scenario where you, as an interpreter, might encounter a consumer who has never worked with interpreters before, then a scenario where the consumer is experienced in working with interpreters. Write a script and practice orienting each of these consumers. Practice orienting a Deaf consumer using ASL. Practice orienting a hearing consumer using spoken English.

About the Author

Colleen Jones is a nationally certified interpreter and presenter from Seattle, Washington. She holds undergraduate degrees from Cal Poly, San Luis Obispo, and Seattle Central Community College, and a master’s degree from Western Oregon University. Colleen’s interpreting work is focused on medical, business, and DeafBlind settings, and she has published research on the topics of gender bias and consumer orientation.

Acknowledgements

This study was originally published as my Master’s thesis at Western Oregon University. I am forever grateful for the support and guidance of my thesis committee members, Ellie Savidge, Amanda Smith, and Dr. Elisa Maroney.

References

Dean, R. K., & Pollard, R. Q. (2005). Consumers and service effectiveness in interpreting work: A practice profession perspective. In M. Marschark, R. Peterson, & E. A. Winston (Eds.), Sign language interpreting and interpreter education (pp. 259– 282). Retrieved from https://intrpr.github.io/library/dean-pollard-practiceprofessions.pdf

Dean, R. K., Pollard, R. Q., & English, M. A. (2004). Observation-supervision in mental health interpreter training. CIT: Still shining after, 25, 55-75.

Hsieh, E. (2010). Provider–interpreter collaboration in bilingual health care: Competitions of control over interpreter-mediated interactions. Patient Education and Counseling, 78(2), 154-159.

Jones, C. (2017). Perception in American Sign Language interpreted interactions: Gender bias and consumer orientation (Master’s Thesis). Western Oregon University, Monmouth, Oregon. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses/41/

Jones, C. (2018, November). Perception in ASL Interpreted Interactions: Consumer Orientation. Paper presented at the Conference of Interpreter Trainers, Salt Lake City, UT. Retrieved from https://www.cit-asl.org/new/perception-in-asl-interpreted-interactions-consumer-orientation/

Kredens, K. (2017). Conflict or convergence? Interpreters’ and police officers’ perceptions of the role of the public service interpreter. Language and Law, 3(2), 65-77.

Llewellyn-Jones, P., & Lee, R. G. (2014). Redefining the role of the community interpreter: The concept of role-space. United Kingdom: SLI Press.

Metzger, M. (1999). Sign language interpreting: Deconstructing the myth of neutrality. Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Registry of Interpreters for the Deaf. (2005). NAD-RID code of professional conduct. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/0B-_HBAap35D1R1MwYk9hTUpuc3M/view

Witter-Merithew, A. (1999). From benevolent care-taker to ally: The evolving role of sign language interpreters in the United States of America. Gebärdensprachdolmetschen: Dokumentation der Magdeburger Fachtagung (Theorie und Praxis 4), Hamburg: Verl hörgeschädigte kinder, 55-64.

Witter-Merithew, A., Swabey, L., & Nicodemus, B. (2011). Establishing presence and role transparency in healthcare interpreting: a pedagogical approach for developing effective practice. Rivista di Psicolinguistica Applicata, 11(3), 79-94.