Practice: The Necessary Preparation for working with People

The Necessary Preparation for working with People

Sarah Hewlett

Maybe you are enrolled in an interpreter education program, or maybe you have graduated from a program already and are back for more training. Or even still, maybe you are looking to start into an interpreting program, have found this resource, and now reading anything you can because you like to prepare. Or even still, maybe you are going to skip the program route altogether and plan to ready yourself for the profession via another avenue; whatever floats your boat. But no matter who you are, there is one real thing – interpreting requires practice.

Learning new skills takes work and becoming proficient at a new skill takes even more work. While studying the theory and fundamentals of a skill are vital, practice is also imperative. Whether you are learning ballet, oil painting, accounting, a musical instrument, cooking, or even interpreting between languages, you cannot become a professional in these areas without a lot of practice. Meadows (2013) researched how American Sign Language/English interpreting professionals experience real-world shock upon entering the profession even though they have had intensive training. What can we do during our training to prepare new professionals as much as possible for real-world situations? We could probably practice more thoughtfully, more often, reflect, and repeat.

An Analogy

For the sake of stepping back for a fresh perspective, follow this analogy. Imagine you want to learn how to play the piano. Where to start? There are so many keys and so many different combinations of keys that sound different when played together. The sheet music looks like a foreign language, and there are even key signatures that situate the whole feeling of a song. A song can make you feel things, guys! There are tempos, accidentals, crescendos, decrescendos, and who knows what else. But you like music and you like how the piano sounds. You have fingers and can push the keys. So, you begin an adventure of learning how to play the piano, with the goal of arriving at the level of piano-playing where you are capable of understanding the music theory so deeply that you can “play” with playing, and sound good doing it! You want to be a professional. You will play a composed song with confidence! You could even use your knowledge of music theory and make up your own song – maybe it won’t be catchy, but you know what cords to play when.

You have to start somewhere. Learn what keys are what, how to read music, how to count measures. There are a lot of rules. You can plink out a scale now, and even play “Hot Crossed Buns” like a boss. You take Piano 101, 102, and 103. Heck, you take all the piano classes your university offers. You got As, and you feel pretty proud of your rather quickly acquired knowledge. Your teachers like the songs you play and said you played them very well. You are so proud of your hard work and new abilities, and you have seen professionals out there who play the songs composers in real time. The professionals watch the composer literally writing the song on paper, or they can even read their minds, it seems. The music is really from the composer in real time, just through the pianist. Listeners can even respond, and it just looks all so useful. You want to be that professional who facilitates music to audiences. You sign up for the classes and, holy smokes, it is harder than you thought, but you have cohort members, instructors, and safe spaces to practice your craft.

You complete your program despite the challenges, and you feel victorious after doing something hard – as you should feel! But now, you are kind of on your own. Sure, there are friendly professionals out there, and there are even unfriendly ones. There are very clear composers, and some that you just do not understand what they want you to do, and the listeners all have opinions too. It feels heavy with so many people involved, and it feels like there was so much more to learn. You did not practice all these songs being composed in the community, but you announce that, “If my program had me practice this, I would have done a better job!”

Okay, you see what we are doing. Sometimes, analogies take us away from how close we are. We have a harder time interrupting to become defensive. Having space from focusing solely on the art of interpreting and using other crafts as examples can take a step back lend us some fresh perspective. Again, maybe you are a student currently in an interpreter training program. This chapter is here to give you another friendly reminder that all the practice you are doing in class, and all the practice you are required to do at home (whether or not you are actually doing it but it is required nonetheless) is worth it. It is worth it if you intentionally practice the skills required to interpret. Maybe you have already completed an interpreter education program and are looking for more training; you definitely know and feel that this is a practice profession where you need a solid foundation to be able to handle the myriad of layers that build an interpreted situation.

Useful Practice: Just One Tool of Many

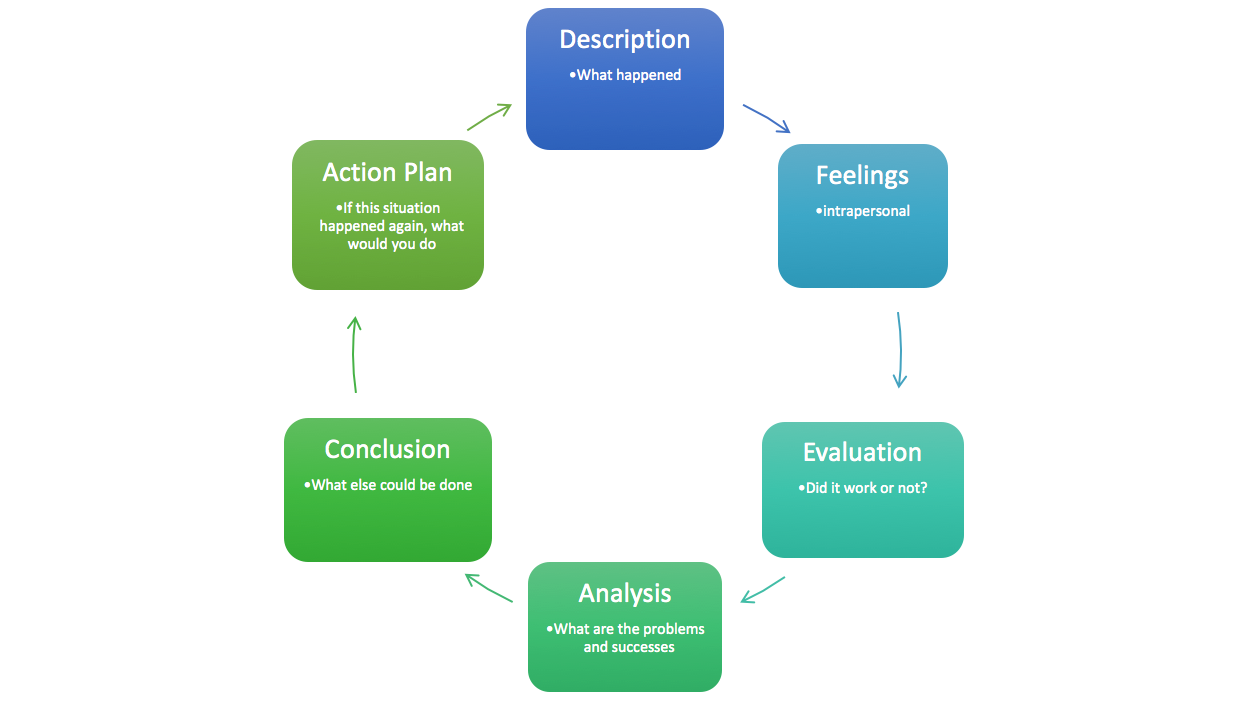

While repetitive practice is crucial to building skills, reflection and implementation of previous learning is the key to improvement. Gibbs (1988) offers a thorough yet simple model that is used widely across practice professions so that each experience can make the next one better. After practicing some aspect of interpreting, whether it be a hard skill or a soft skill, a student can isolate a demand from their experience and follow Gibb’s Reflective Cycle to extrapolate to brainstorm new controls on how to respond should the demand arise in the future. For example, let us use Isabella Interpreter as a hypothetical illustration. Isabella Interpreter is a student in an interpreting program, who is currently enrolled in an Interpreting Practicum class. For this class, students are placed in authentic postsecondary classes to practice interpreting lectures without the presence of a Deaf person. Isabella has a rough experience being thoughtful of her work because she feels that the absence of a Deaf person makes it pointless, yet her whole term will be spent in this setting so that she can practice in a risk free environment. Isabella Interpreter needs to reflect on her intrapersonal feelings and make a plan for how to get the most out of this practice environment. She can follow Gibb’s cycle to strategically plan to make her next practice session more beneficial. Figure 1 shows Gibb’s Reflective Cycle.

Figure 1. Gibbs’ Reflective Cycle. Adapted from Gibbs, G. (1998). Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Future Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic. Oxford.

Gibbs’ model provides a very useful framework that can be cycled through as often as necessary. Isabella Interpreter might identify her feelings of mock interpreting feeling pointless, and go through the cycle as follows:

- Description: I feel ridiculous interpreting from English to ASL with no Deaf person present. The room is full of hearing people. I don’t even know if a Deaf person would understand what I’m doing in here because I can’t see them. There is no backchanneling.

- Feelings: ridiculous, annoyed and frustrated this is an assignment, maybe embarrassed

- Evaluation: I was not thoughtful while practicing today because I just felt silly. I will be in this class all term. This did not work for me.

- Analysis: The problem, for me, is that I feel like I need to look at a Deaf person while interpreting. But for a reason, there is no Deaf student in here. This is a conflict of what I feel like I need and the demand of the situation.

- Conclusion: I see two options. One is that a Deaf person could come to class. A second option is that I can let go of the need to have a consumer. Perhaps I can accept the demand as it is, and focus my energy on interpreting to a camera that I can later watch the recording and analyze my interpretation.

- Action Plan: If this situation happened again, and it will in a couple days, I will put a imagine a Deaf person is watching me. I will set up my phone to record my work to later analyze, but in the moment, I will imagine that my Deaf friend is attending class from a distance, and that I am the interpreter.

This is a brief example of one way this tool could be used. There are other tools available that promote reflection, identification of barriers, and encourage brainstorming action plans, but for the sake of starting with something, this cycle is helpful in identifying problems and potential ways to approach them the next time they arise, for problems will always arise.

Potential for this Section

This section is one slice of a larger work that can include reminders of intentional practice focusing on the technical skills of interpreters, as well as the soft skills that are required in the field. Both technical and soft skills can be worked on separately, and activities can be developed to combine the two in preparation for entering the field where people are depending on your interpretation for participation. This section would benefit from chapter contributions including but not limited to:

- Narratives from the perspective of recent graduates working as professionals, describing the challenges they faced and how they overcame them.

- Practice activities

- Soft-skill practice activities for interpreters

- How to handle resistant participants who prefer not to have an interpreter present

- How to practice professional boundaries with participants who continually try to pull an interpreter out of their professional duties

- How to behave during down time

- Technical-skill practice activities for interpreters from English to ASL

- Technical-skill practice activities for interpreters from ASL to English

- Soft-skill practice activities for interpreters

The notion of practice being required to be proficient is apparent, but knowing how to practice is a skill on its own. Even professionals with years of experience can get into ruts or face challenges in their work that require reflective and intentional practice so the challenge can be overcome. This section could become a resource of a whole host of activities and ideas that students and professionals could try until they find a tool that clicks for them.

References

Gibbs, G. (1988). Learning by Doing: A guide to teaching and learning methods. Further Education Unit. Oxford Polytechnic: Oxford.

Meadows, S. A. (2013). Real-world shock: transition shock and its effect on new interpreters of American Sign Language and English (Master’s thesis). Western Oregon University, Monmouth, Oregon. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/theses/8