3.6 Individual Enforcement of Civil Rights

While Department of Justice actions allow the federal government to bear the burden of identifying and investigating problems and then enforcing its own laws, more isolated or individual violations are unlikely to be federal government enforcement priorities. In those cases, individuals can and do initiate lawsuits. Impacted individuals might sue a government official or entity—such as a corrections official or a police department—to enforce their civil rights under the Constitution or statutes. These lawsuits take many forms, but they generally claim that a person’s rights were violated and that they suffered some injury as a result of that violation. Lawsuits like this can be critically important to enforcing laws or constitutional provisions that—like so many civil rights provisions—are “on the books” but not being observed in reality.

ADA Enforcement Lawsuits

The ADA is one vehicle for individual civil rights claims. The ADA does not provide for monetary damages; lawsuits may demand change, but they will not compensate a plaintiff. However, attorney fees may be recovered, which can encourage legal service organizations to represent ADA plaintiffs and causes. Additionally, individual states have laws based on the ADA that do allow the collection of monetary damages. Those laws are beyond the scope of this text but are certainly worth investigating in your jurisdiction.

Federal ADA lawsuits claiming criminal justice-related violations of rights can be brought under several different legal “theories” or approaches, all of which essentially assert that a state or local government entity (e.g., a department of corrections) failed to do something that was required to create equity for people with disabilities. An ADA lawsuit might focus on the wrongful arrest of a person, the failure to accommodate a disability, or the failure to train relevant personnel, resulting in disability-related harm. These different theories have a good deal of overlap, and a single set of facts might allow arguments or claims based on different theories (Levin, 2017). Consider how each of the scenarios described below could be framed in different ways to challenge criminal justice professionals’ conduct, preparation, or knowledge based on the ADA:

- Wrongful arrest might be alleged when a person suffering a mental health episode appeared intoxicated and was detained for that behavior. The arrest could be an innocent accident, or it could be a wrongful arrest due to the officer’s unacceptable failure to appreciate information that reasonably would have informed them that the person was displaying signs of a disability rather than voluntary intoxication.

- A reasonable accommodation in response to a mental health crisis call might involve law enforcement including mental health professionals to help avoid a dangerous escalation of events. A deliberate failure to take this safety measure might provide grounds for a complaint of failure to accommodate.

- Finally, failure to train could involve an assertion that a criminal justice professional was not provided with adequate necessary training to keep a person with a disability safe in a particular situation—perhaps a seriously depressed person in jail who was unrecognized and engaged in self-harm. When the failure to recognize the situation and keep the person safe is attributable to a failure to provide proper training, an ADA violation may exist.

The U.S. Department of Justice has published tips and suggestions for criminal justice entities, encouraging adequate training as well as other measures to comply with Title II of the ADA—and presumably avoid legal action (U.S. Department of Justice, Civil Rights Division, 2017). However, as discussed in the next sections, individual claims like those described here are both difficult to bring and challenging to win, even when plaintiffs have experienced serious harm.

Outcomes in Civil Rights Lawsuits

Whether brought pursuant to the ADA or on other legal grounds, civil rights lawsuits are typically complex, lengthy, and expensive. Sometimes these lawsuits can vindicate a particular individual’s rights, and sometimes they promise broader change by establishing a new rule or precedent that applies beyond an individual case. However, these are hard-won victories, and often plaintiffs have a very challenging time even finding and paying skilled legal representatives to pursue these lawsuits. Nevertheless, there are notable examples when lawsuits have brought critical change to the treatment of people with mental disorders.

Advocacy organizations like the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) or disability rights groups may represent individuals in bringing these lawsuits, as they also further the organization’s larger advocacy objectives. For example, the nonprofit Disability Rights Oregon has been engaged in on-and-off litigation for more than 20 years now, ensuring that people with mental disorders who are too impaired or sick to proceed in criminal cases do not languish in jail for weeks and months while awaiting admission to the Oregon State Hospital for evaluation and treatment. If you would like to learn more about this litigation, you can read about Disability Rights Oregon’s mental-health-related work at Disability Rights Oregon [Website].

The Atlanta Legal Aid Society brought a disability rights lawsuit on behalf of Lois Curtis (introduced at the beginning of this chapter) in 1995, resulting in what is usually viewed as the most important Supreme Court decision on the rights of people with mental disorders (figure 3.20). The case of Olmstead v. L.C. (1999) was based on the Americans with Disabilities Act and challenged the disability-based confinement of Curtis and her co-plaintiff. The Olmstead case established the important principle that people with disabilities should not be segregated without justification (Bazelon Center for Mental Health Law, n.d.). See the Spotlight in this chapter to learn more about the Olmstead plaintiffs and their case.

Although Olmstead was not a criminal justice case specifically, its principles have the potential to inform approaches to people with mental disorders in the criminal justice system. Criminal justice scenarios are a common place for separation to occur in the name of protecting people with mental disorders or protecting others from people with mental disorders. Under the law after Olmstead, less restrictive environments have to be considered for people with mental disorders who might otherwise be segregated in the name of providing care. Olmstead has been cited to encourage the diversion of people out of the criminal legal system (discussed in Chapter 4), protest the use of very restrictive or solitary placements in prison, challenge the institutionalization of people before and after criminal convictions, and object to jail-based treatment for accused people who are mentally ill (discussed in Chapter 9). Students and criminal justice professionals should consider how the rule against segregation expressed by Olmstead, which is contrary to the entire notion of imprisoning people with mental disorders, might be employed to reform and reduce incarceration more broadly (McDonough, 2021; Morgan, 2020).

Constitutional Claims: Right to Care and Treatment

Individuals in the criminal justice system can bring claims based on their rights under the Constitution. For example, one particular issue that frequently applies to people with mental disorders in custody is the right to receive adequate medical treatment—including mental health treatment—based on the Eight Amendment to the Constitution. Similarly, prisoners have a related right to be protected from self-harm in the event they are suicidal. In lawsuits regarding these rights, failure to provide adequate care is framed as a violation of a person’s Eighth Amendment right to be free of cruel and unusual punishment.

Constitutional cases are very difficult for plaintiffs to prove and win, as they typically require evidence that the offending jail or prison personnel knew of a serious problem or threat and chose not to provide the required help or treatment, a challenging standard called deliberate indifference (Farmer v. Brennan, 1994). Nevertheless, despite significant obstacles, people injured by lack of mental health care in custody do bring lawsuits, and occasionally they win. When lawsuits based on lack of treatment are successful, and even sometimes when they are not, they can bring attention to problems and help carve out the increasing expectation that the criminal justice system must meet the legitimate needs of people with mental disorders. See Chapter 7 for additional discussion of deliberate indifference in the context of prison-based health care.

Although any number of cases could serve as an example of private litigation being used to enforce prisoners’ rights to mental health care, an Arizona case that was partially resolved in the summer of 2022 is illustrative of both the importance of those cases and the difficulties they pose (figure 3.21). That case, Jensen v. Shinn, was filed by a group of prisoners represented by the ACLU and the Arizona Center for Disability Law in 2012.

The Jensen prisoner plaintiffs were not asking for monetary damages; they were asking for the court to give them some relief from their oppressive living conditions. After twelve years of fighting Arizona prison officials—and producing mountains of evidence of pervasive failure to meet the medical and mental health needs of prisoners in numerous ways—the plaintiffs finally got the case to trial, and a judge ultimately found that the prisoners’ rights had been violated (ACLU, 2024). The evidence showed, overwhelmingly, that health care in the prison was grossly inadequate and that hundreds of people were being kept in restrictive maximum custody for no legitimate reason. In the judge’s 200-page order describing her findings, she characterized prison conditions as cruel and shocking, and she ordered many changes be made—changes that lawyers must now fight to put into effect (ACLU, 2024). If you are interested, you can read more about the ongoing Jensen case, now called Jensen v. Thornell, at the Arizona Center for Disability Law [Website].

SPOTLIGHT: Integration of People with Mental Disorders: The Olmstead Case

In the 1990s, two women, Lois Curtis ( “L.C.”) and Elaine Wilson, both of whom had mental disorders, were confined to a Georgia hospital where they received care funded by the state. Curtis had been at the hospital since she was 11 years old; Wilson had been in and out of many institutions, eventually landing at the hospital. Over time, it became clear to Curtis and Wilson, and to their care providers, that the women were capable of living in less restrictive environments in the community. They both wanted to and were capable of living in home-like settings with proper support. Neither woman required or desired confinement or the care of a hospital. However, the State of Georgia, via its Department of Human Services, refused to fund more independent care, and so the women remained in the hospital—against their wishes and at taxpayer expense. Their hospitalization continued for years.

Curtis and Wilson, represented by an Atlanta Legal Aid lawyer, eventually sued Tommy Olmstead, the Georgia Department of Human Services commissioner. Olmstead’s refusal to shift funding to a community setting had kept Curtis and Wilson segregated in a hospital, but his name was about to become synonymous with the idea that segregation of people with disabilities is wrong (Appelbaum, 2019).

Curtis and Wilson’s lawsuit pointed out that Olmstead’s actions violated Title II of the ADA, which regulates state and local governments. People without their particular disabilities would have had the opportunity to live in the community, and they should have the opportunity to do the same. The ADA, they contended, gave them the right to receive services they might need in the same way nondisabled people would, in a less restrictive, integrated, community-based setting. This right should not be overshadowed by Georgia’s apparent preference for funding institutional care. The women argued that their segregation in a hospital was unnecessary and violated the ADA.

The case made its way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which agreed with Curtis and Wilson. The court ruled that segregation of these women in a hospital—not allowing them to live with others in the community—was not required by the women’s disabilities, but rather was due to the unwillingness of authorities to reasonably modify their response. The perpetuation of unnecessary segregation of these women was discrimination based on disability, which violated the ADA.

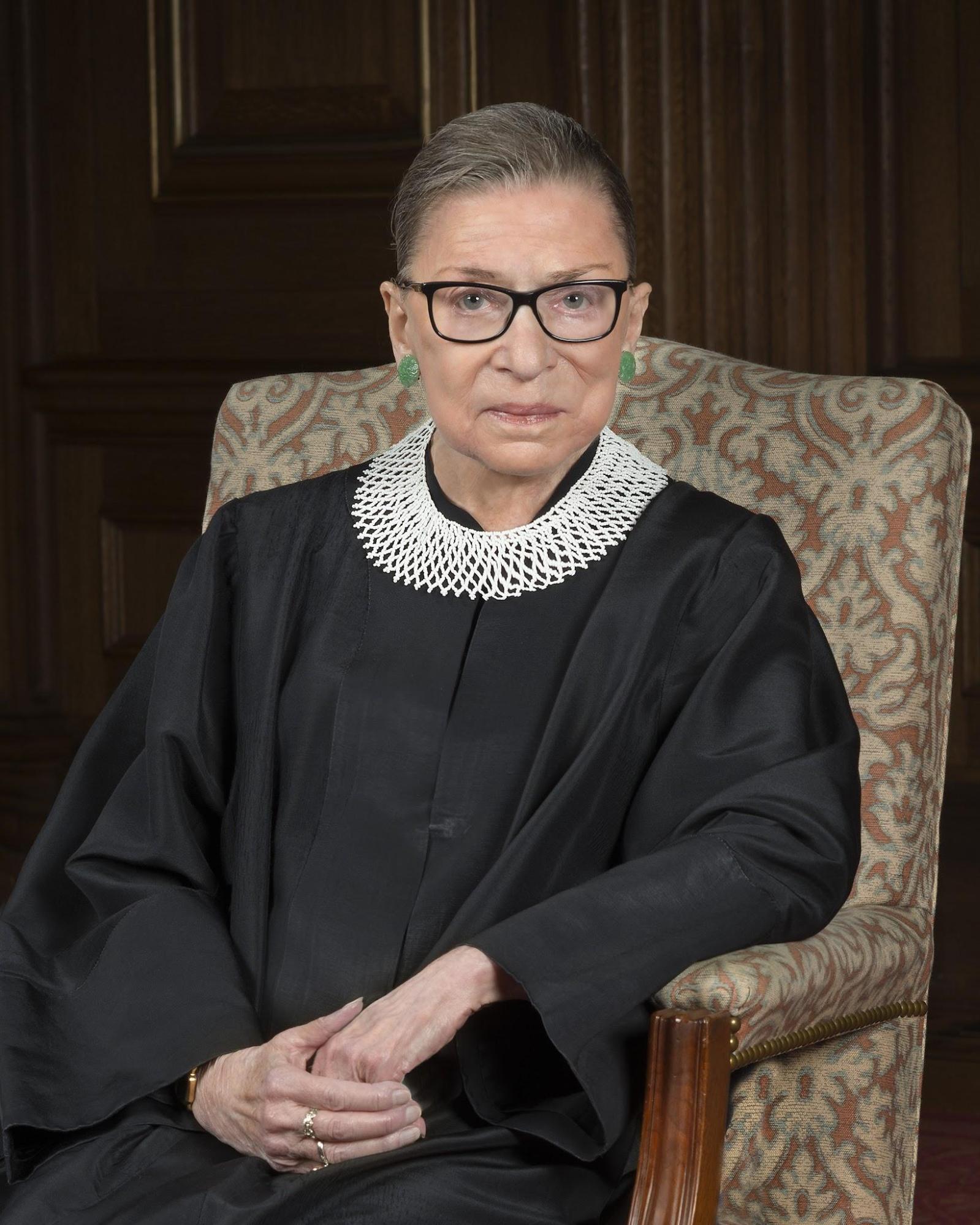

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg (figure 3.22) wrote the court’s 1999 opinion in Olmstead, emphasizing that this type of segregation imposed upon people with mental disorders “perpetuates unwarranted assumptions that persons so isolated are incapable or unworthy of participating in community life” and observed that institutional confinement “severely diminishes the everyday life activities of individuals.” (Olmstead v. L.C., 521 U.S. at 583).

The Olmstead decision was transformational. For Curtis and Wilson, their desire to live in the community was vindicated. For people who experience mental disorders throughout the nation, in all manner of institutional settings and supervised by local governments, the implications of Curtis and Wilson’s case were enormous. The Supreme Court had affirmed that people with disabilities cannot be kept in a limiting or confining environment based on government preference when that type of removal from the community is not justified by the real needs of the person’s care. If people can be included in the community, they should be.

Elaine Wilson died just a few years after she was finally allowed to live in her own home with a caregiver. Like her co-plaintiff, Wilson had begun her life of segregation as a child, after a high fever left her with disabilities, and she was moved in and out of facilities (which she despised) dozens of times. Reportedly, once Wilson was finally living in the community, she experienced joy in her new life: “‘We saw Elaine became very independent and very proud of her independence,’ [a caregiver] said. ‘She loved to shop at Walmart and Kmart and the grocery store. One of her hobbies was to clip grocery coupons in the Sunday paper. She spent hours picking out greeting cards. She loved to visit people and have people come visit her. She was a very social person’” (Henry, 2004).

Until her death in 2022, Lois Curtis also engaged in her community and worked as an artist, pursuits that were not out of reach despite her diagnoses of developmental disability and schizophrenia, once her environment had adjusted to her needs. If you would like, you can see some of Curtis’s artwork [Website] online. Curtis gave one of her self-portraits to President Barack Obama in a ceremony (pictured in figure 3.23) celebrating her advocacy in the Olmstead case (Brandman, 2022).

Lois Curtis was asked in an interview, years after her Supreme Court case, what she would wish for all the people she had helped to move out of institutions and live in their communities. Curtis responded: “I hope they live long lives and have their own place. I hope they make money. I hope they learn every day. I hope they meet new people, celebrate their birthdays, write letters, clean up, go to friends’ houses and drink coffee. I hope they have a good breakfast every day, call people on the phone, feel safe” (Curtis & Sanders, n.d.).

Of course, the victory of Lois Curtis impacted all people with disabilities, but many also see particular meaning in a Black woman fighting for and establishing her right to choice and bodily autonomy. Watch the short video linked in figure 3.24 to hear that perspective from people who admire her legacy.

Licenses and Attributions for Individual Enforcement of Civil Rights

Open Content, Original

“Individual Enforcement of Civil Rights” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

“SPOTLIGHT: Integration of People with Mental Disorders: The Olmstead Case” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

Figure 3.20. Photo of Supreme Court building by Claire Anderson on Unsplash.

Figure 3.21. “Arizona prison facility” by Xugardust is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Figure 3.22. “Ruth Bader Ginsburg 2016 portrait” by Steve Petteway is in the public domain.

Figure 3.23. Photograph of Lois Curtis with President Barack Obama by Pete Souza is in the public domain.

Open Content, All Rights Reserved

Figure 3.24. Lois Curtis Documentary Trailer – 2023 Anniversary of Olmstead v. L.C. (Lois Curtis) by Bazelon Center is licensed under the Standard YouTube License.