8.5 Interventions for Successful Reentry

Although we may appreciate many of the needs and challenges facing a person in the reentry process, the question remains: how do we meet these needs? Numerous interventions exist that can help people living with mental disorders who are reentering the community from jail or prison. These interventions can reduce recidivism as well as accomplish other goals and measures of success, such as addressing mental health symptoms or increasing access to housing and social support.

Three specific forms of intervention are discussed here, chosen because there is significant evidence to support their use in helping formerly incarcerated people with mental disorders. As you read, consider why the interventions discussed here may be particularly helpful to the population that is the focus of our text. These three evidence-based, or proven effective by research, interventions are:

- Medications for substance use disorders

- Case management services

- Peer support and patient navigation

Medications for Substance Use: MOUD and MAUD

Chapter 7 discussed the use of medications for substance use disorders in prisons and jails. Although these medications are highly effective when started in custody and continued in the community, there are barriers to their use in custody. These barriers include security concerns, lack of qualified medical staff to oversee medications, and state or local regulations that limit the prescription of the medications. In the community, there are fewer barriers to medication use, and medications are more frequently employed as a highly effective tool for treating people who experience substance use disorders alone or in combination with other mental disorders.

Medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) and medications for alcohol use disorder (MAUD) are terms used for these medication-based treatments for specific substance use disorders. Medication-assisted treatment, or MAT, is a more general term that is still frequently used to describe these same treatments. The specific and slightly different terms MOUD and MAUD are preferred by some to avoid the word “assisted” in MAT, which implies that medication is merely supplemental or temporary—of “assistance”—in substance use treatment. Instead, the terms MOUD and MAUD indicate that medications for substance use disorders are central to a patient’s treatment, similar to the way other psychiatric medications (e.g., antidepressants or antipsychotics) are used to treat mental disorders (National Institute on Drug Abuse, 2021).

MOUD and MAUD are important reentry interventions because of the very high numbers of people leaving incarceration who meet the criteria for substance use disorders: around 58% of people in state prisons and 63% of people in jails. By comparison, only about 5% of the general adult population meets these criteria (SAMHSA, 2023). MOUD and MAUD are also important because they work. For people reentering the community from criminal justice settings who have certain substance use disorders, MOUD and MAUD are key components of recovery, the process of change through which people improve their health and wellness. These medication approaches lower rates of opioid misuse, decrease fatal and non-fatal overdoses, increase treatment retention, and lower rates of re-incarceration.

Despite the effectiveness of MOUD and MAUD, they are still underused—in some cases due to real barriers and in others due to misperceptions. For example, there is a misunderstanding that these medications must be used alongside other substance use treatment modalities. However, while MOUD and MAUD can be used in combination with counseling and other behavioral health interventions to provide a more comprehensive approach to recovery, the medications are also beneficial alone. Additionally, the use of these medications is not as strictly regulated as some may believe. In fact, most forms of MOUD and MAUD can be provided in various settings, including outpatient treatment programs, physician offices, clinics, and residential treatment programs.

Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

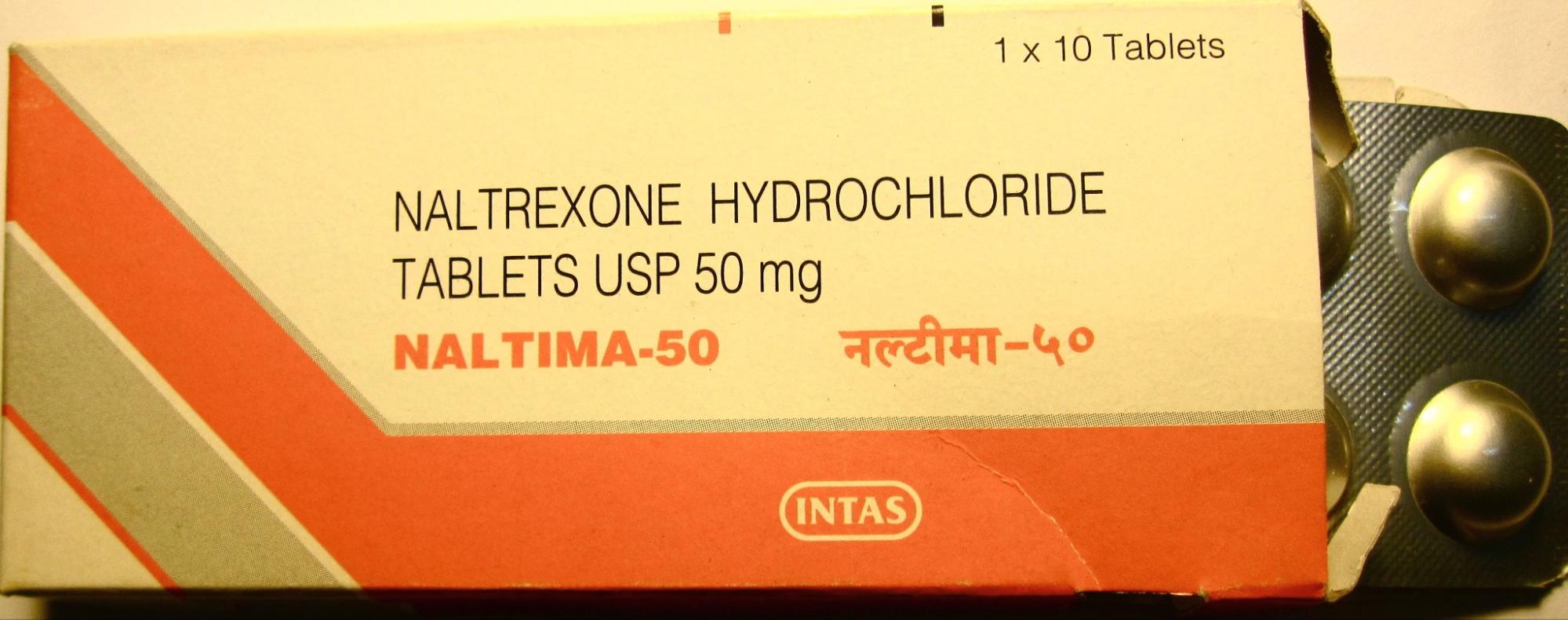

The FDA has approved three medications for treating opioid use disorder, a substance use disorder involving the use of opioid drugs, which include heroin, fentanyl, and prescription opioids (e.g., OxyContin). The medications for opioid use disorder—buprenorphine, methadone, and naltrexone—help prevent deadly overdoses and sustain recovery, and they accomplish these goals using slightly different mechanisms. Buprenorphine works to lower physical dependence on opioids and increase safety in case of overdose. It can be prescribed or dispensed in physician offices. Methadone reduces opioid craving and withdrawal, and it blocks the effects of opioids. Methadone must be dispensed by certified opioid treatment programs. Naltrexone lowers opioid cravings by binding and blocking opioid receptors. Naltrexone (figure 8.10) can be prescribed by any practitioner who is licensed to prescribe medications, and it can be administered in oral form or as an extended-release intramuscular injectable.

Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder

Medications for Alcohol Use Disorder (MAUD) is an approach for treating alcohol use disorder, a substance use disorder involving recurrent and harmful use of alcohol. Treatment with MAUD reduces alcohol use and helps sustain recovery. The most common FDA-approved medications used to treat alcohol use disorder are acamprosate, disulfiram, and naltrexone (figure 8.11). Disulfiram is an oral medication used to prevent and limit alcohol use for individuals by causing negative physical symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, that can deter alcohol use. Acamprosate is an oral medication that is used to maintain recovery by reducing the negative symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. Naltrexone is used to treat alcohol use disorders in the same way it treats MOUD—by reducing alcohol cravings by binding to endorphin receptors and blocking the effects of alcohol. Naltrexone in pill or injectable form can be prescribed by any practitioner who is licensed to prescribe medications.

Outcomes Associated With MOUD and MAUD

Studies gathered and relied upon by the federal government demonstrate that, for people reentering communities from criminal justice settings, MOUD and MAUD have strong positive outcomes in the areas of recidivism, substance use, and treatment engagement. For example, people treated with MOUD or MAUD have lower rates of re-incarceration than people who are only given counseling. People treated with MOUD and MAUD have lower self-reported drug and alcohol use and lower rates of positive drug screens. They also have a decrease in overdoses. Finally, people treated with MOUD and MAUD are more likely to engage in other substance use treatment in the community and more likely to continue participation. For details of the various studies supporting these conclusions, feel free to take a look at SAMHSA’s publication upon which this chapter is based [PDF].

For people with opioid use disorders, starting MOUD before leaving jail or prison is associated with the best outcomes. Providing MOUD, in addition to a strong referral to a community-based MOUD treatment provider upon release, is effective and results in significant positive outcomes for individuals with opioid use disorders. However, as noted, this may not always be possible given barriers to in-custody use of these treatments.

Case Management Services

Case management is another intervention that helps people with mental disorders as they reenter the community. In case management, a provider connects clients to services in the community, including mental health and substance use treatment. For people returning to the community from prison or jail, case management is most effective when it includes a direct handoff from in-custody providers to community services. A direct link ensures continuity of care—or uninterrupted access to care—between criminal justice and community settings. Case managers can serve in various roles (e.g., social workers, therapists, probation officers) depending on the setting, and they often have behavioral health degrees, such as in psychology or social work (figure 8.12).

Case Management Guidelines

In keeping with the RNR model of directing service where it is needed, case management services are generally provided to people who are at medium or high risk of reoffending. A case manager enacts a plan that is built on a person’s identified needs, specifying appropriate interventions or services. All agencies interacting with the person (including jail, probation, and community-based service providers) should use a single case plan that, ideally, is created in custody and follows the person into the community upon release.

The intensity and duration of case management can be tailored to fit the person being supported. It can begin before or after a person is released from custody, and it can continue for just a few months or longer. Case managers typically interact with clients more frequently at the beginning and then at a lower frequency as the intervention continues. For example, a case manager might meet with a person receiving services 1 month before release, then for three sessions in the 1st month after release, and then monthly for the remainder of a year. Or, for a shorter term, the case manager might meet with the person before release, then every week for 3 months with an option to follow up as desired. Case managers can have contact via visits in the field, office visits, or by phone.

Case Management Outcomes

Studies have considered the impact of case management on recidivism as well as other factors, such as mental health and general well-being, substance use, treatment engagement and retention, employment, education, and housing. Overall there are significant, positive outcomes on these factors. Case management has certainly emerged as an effective tool in decreasing recidivism, including both arrests for serious charges and rates of conviction. Case management is associated with increased participation in mental health and substance use treatment, higher levels of social support, and reduction in substance use. People receiving case management after release also received more employment and education services in the months after release than those without case management. They had increased rates of employment and increased educational attainment (for example, attending a college or vocational program upon release). There have also been studies suggesting positive impacts on housing. Notably, these outcomes point to successes beyond measures of recidivism. Case management appears to produce these positive results across gender, racial, and ethnic lines. For details of the various studies supporting these conclusions, feel free to take a look at SAMHSA’s publication upon which this chapter is based [PDF].

Peer Support and Patient Navigation

Peer support and patient navigation are, together, a third form of intervention that positively impacts people living with mental disorders after their release from custody (figure 8.13). Both of these forms of support involve hands-on services that are typically combined with other interventions, such as case management or medications for substance use disorders.

Peer Support

Peer support workers (also known as peer navigators, peer recovery coaches, or simply peers) have lived experience of mental health conditions and/or substance use disorders, and in some cases, criminal justice involvement. Peers have experienced these events themselves, have been successful in the recovery process, and now help others experiencing similar challenges. Peers share their lived experiences with the person they are helping, as they improve access to mental health services, substance use treatment, and other social services (e.g., housing, transportation, food, training and education, and employment). Through shared understanding, respect, and mutual empowerment, peer support workers help clients enter and stay engaged in the recovery process and reduce the likelihood of a recurrence of symptoms.

Patient Navigation

Patient navigation is the use of trained healthcare workers to reduce barriers to care. Patient navigators, like peers, can help clients navigate care and treatment, with a particular focus on dealing with complex healthcare and social services systems. Navigators help connect their clients with services, schedule appointments, and communicate with providers. While peers always have lived experience, patient navigators sometimes have lived experience in addition to other expertise.

Peer Support and Patient Navigation Outcomes

Peer support and patient navigation have positive impacts on several factors, including mental health and general well-being, substance use recovery, and treatment engagement—often for significant periods after release from custody. Although peer support is less studied than patient navigation, peer support is well-understood to be effective in improving mental health and treatment motivation, while reducing the use of substances. These outcomes are especially important when researchers want to look beyond recidivism as a measure of “success” in understanding how to help people in reentry. While these outcomes may be difficult to measure, they are important to acknowledge.

Peer support and patient navigation can occur in any setting and can be effective for any gender, racial, or ethnic group. These interventions often begin before release from custody, allowing the same peer or navigator to support a person as they move into the community. The intensity and duration of peer and patient navigation can vary based on individual needs. These supports have been effective in studies where they were provided for periods ranging from three months to twelve months, with meeting frequency and length adjusted for individual preferences. For details of the various studies supporting these conclusions, feel free to take a look at SAMHSA’s publication upon which this chapter is based [PDF].

Licenses and Attributions for Interventions for Successful Reentry

Open Content, Shared Previously

“Interventions for Successful Reentry” is adapted from Best Practices for Successful Reentry From Criminal Justice Settings for People Living With Mental Health Conditions and/or Substance Use Disorders by Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), which is in the Public Domain. Modifications, by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0, include condensing and revising the content.

Figure 8.10. Naltrexone Hydrochloride marketed under the name Naltima-50 by Mahamaya1 is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

Figure 8.11. Photo by Alexander Grey is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 8.12. Photo by Iwaria Inc. is licensed under the Unsplash License.

Figure 8.13. Photo by Priscilla Du Preez 🇨🇦 is licensed under the Unsplash License.