1.3 Mental Disorders in Modern Times: The Rise of Institutional Treatment

Somewhat later, America had its own “father of psychiatry,” Dr. Benjamin Rush, who in 1812 wrote the first psychiatry textbook to be printed in the United States: Observations and Inquiries Upon the Diseases of the Mind (Penn Medicine, n.d.-a). In addition to practicing medicine, Rush was a signer of the Declaration of Independence and a civic leader who was outspoken in his opposition to slavery and support of education—including the education of girls (University of Pennsylvania, n.d.). However, some of Rush’s voiced beliefs conflicted with his actions, as he is reported to have been a slaveholder for a period (Dickinson College, n.d.). Rush’s progressive views, limited as they were, extended to the treatment of patients with mental disorders.

The Creation of State Hospitals

By the early 1800s, American communities following in European footsteps had created some asylums for people with mental disorders. The higher-end asylums followed the lead of the French doctor Pinel, engaging in what was called “moral treatment” of patients. Benjamin Rush was a practitioner of this approach. Moral treatment for people with mental illness was based on the idea that patients could become well if they were treated kindly and in ways that appealed to the supposed “rational” parts of their minds.

Moral treatment specifically rejected the harsh treatments that had previously been used to respond to mental disorders, as well as the negative judgment or thinking that an ill person was somehow “bad” (Penn Medicine, n.d.-b). Instead, the moral approach idealized peace, quiet, and seclusion. American asylums, as opposed to the dungeons of 17th-century Europe, were intended to provide this peaceful atmosphere in hopes of curing their residents (D’Antonio, n.d.).

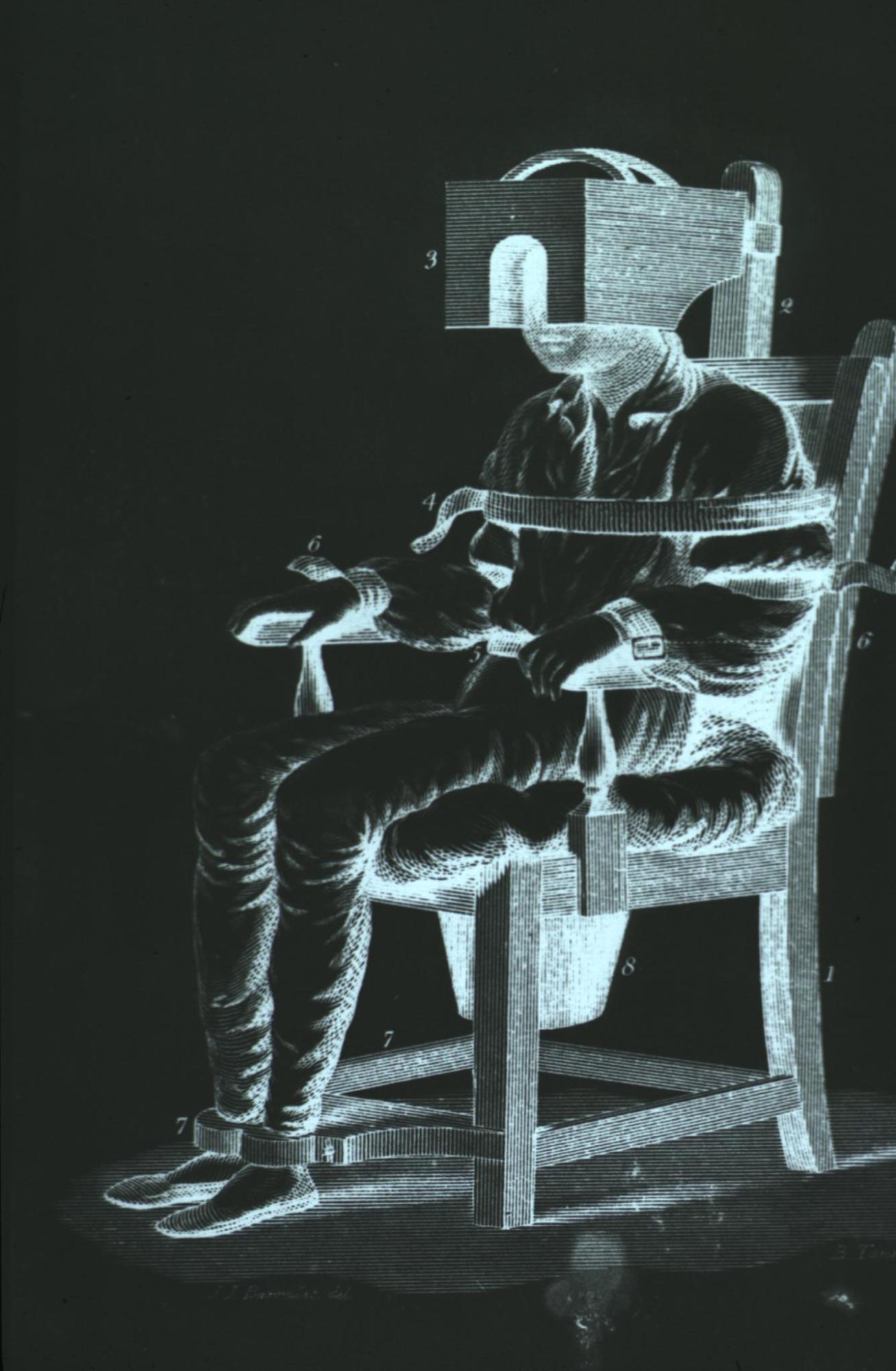

The active treatments for mental illness offered in American asylums remained very limited in the 1800s. Treatments still included older approaches such as bloodletting, but Dr. Rush also introduced some new innovations. He created a “tranquilizer chair” (figure 1.7) and a “gyrator,” which would spin restrained patients to encourage better blood circulation. The tranquilizer chair especially, though obviously troubling by today’s standards, was a step forward in that it was intended to calm patients by restraining their heads and bodies without the use of an even harsher straightjacket (Penn Medicine, n.d.-b).

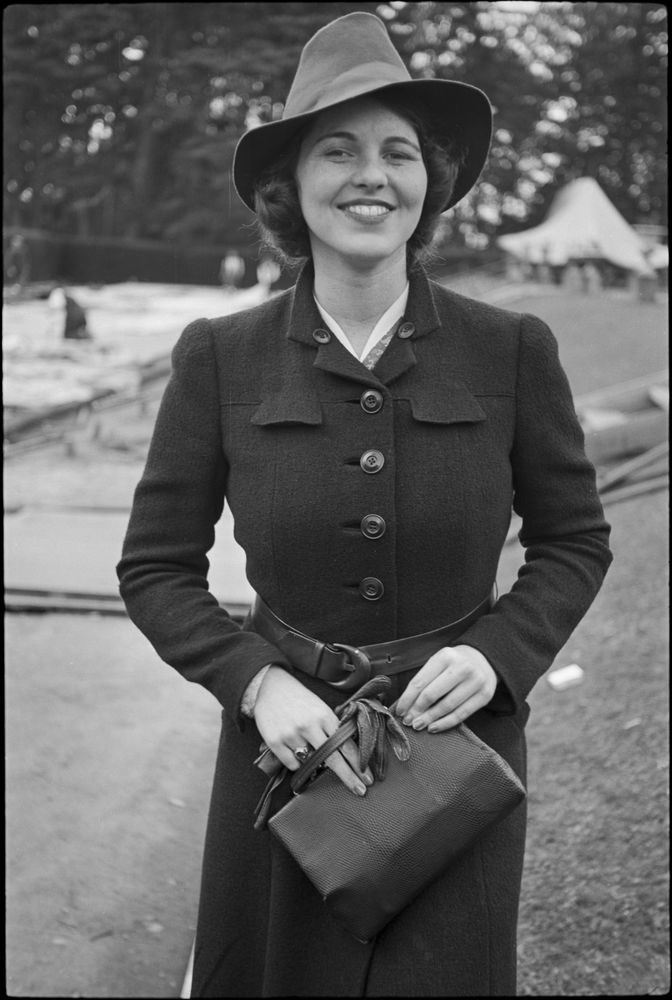

Although more expensive private asylums had incorporated moral treatment approaches by the mid-1800s, many poor American patients with mental disorders still languished in jail-like facilities (D’Antonio, n.d.). This state of affairs inspired a school teacher-turned-reformer named Dorothea Dix (figure 1.8) to push for change, specifically the establishment of what would be known as state hospitals. These early state hospitals were psychiatric facilities in the model of the asylum and were funded by the government to serve the public.

Dix had reportedly visited jails for religious outreach, leading her to become concerned about incarcerated people with mental illness and then about the treatment of this group generally. Recognizing the mistreatment of people with mental illness as a widespread problem in America, Dix traveled throughout the country during the 1850s and 1860s. She testified to state legislatures and Congress, urging lawmakers to move people with mental illness out of jails and jail-like institutions. She criticized the cruel treatment of people with mental illness, which included putting them in cages and using painful restraints (Parry, 2006).

Dix proposed that states create special, publicly funded hospitals to house this population. These new facilities imagined by Dix would be dedicated to treatment for those with mental illness, and she believed they would offer the opportunity for better treatment and even cures for many patients. Dix’s advocacy contributed directly to the creation of more than 30 state hospitals. By 1870, nearly every state had a public hospital built on the principles of moral treatment (D’Antonio, n.d.; Parry, 2006). Dix’s advocacy and results were impressive, especially considering that her activism preceded the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment, which allowed women to vote, by more than 50 years (Parry, 2006).

However, over time it became clear that state hospital facilities promised more than they were able to deliver. In many cases, state hospitals were an improvement over previous facilities, but they offered no actual cure to most of their inhabitants (Tracy, 2019). In fact, the hospitals were increasingly used to house additional populations—such as the elderly or people with various disabilities beyond mental illness—who needed state-funded care but were not moving toward “recovery.” The state hospitals, full of patients likely needing care for their entire lives, exceeded their capacities and their limited resources (D’Antonio, n.d.).

By the late 1800s, state hospitals were overwhelmed. They were overcrowded and increasingly filthy, and they offered very little in the way of actual treatment to their residents (Spielman et al., 2020; Farreras, 2023). The practice of institutionalization, the segregation and confinement of people with disabilities or mental illness in facilities rather than supporting their integration into communities, was firmly entrenched (Spielman et al., 2020). Ultimately, the new hospitals championed by Dix were simply the latest way to confine and remove the unwelcome population of people with mental disorders in American society.

Stories of the horrors at state hospitals abound. One example, the Willard Psychiatric Center, originally called the Willard Asylum for the Insane, first opened in upstate New York in 1869 and remained open for 130 years (Willard Psychiatric Center Collection, n.d.). At Willard, reported “treatments” included submerging patients in ice-cold baths even as wintertime temperatures in the facility were said to be cold enough to freeze a glass of water left on a table overnight (Spielman et al., 2020).

Willard was not alone in its miserable treatment of patients; rather, it was unfortunately typical of state institutions at the time. Reports on similar hospitals reveal that people were often treated cruelly—including enduring beatings and sexual abuse. Sometimes, experiments were performed on unknowing residents (Brown, 2021). Because every state built an institution for its mentally ill and disabled residents, nearly every state has a history of an abusive institution that existed for decades, at least, extending into recent history. Some of these histories remain more obscure than others, with residents often not able to express and publicize their experiences.

Oregon Institutions

Oregon had its own infamous institutions, including the Fairview Training Center. Over the course of its life, Fairview confined thousands of people, from young children to the elderly, with a range of disabilities that often included mental disorders. Fairview opened in 1908 as “an institution for the feebleminded, idiotic, and epileptic” with 39 “inmates.” It eventually became Oregon’s largest institution, housing 3,000 residents at its peak. Fairview residents were restrained, whipped, drugged, and locked into small cages. Disabled children often entered Fairview and remained confined there for their entire lives. Thousands of Fairview residents endured forced reproductive sterilizations that continued to occur through the 1970s (James, 2015). Watch the video in figure 1.9 to hear from Fairview residents who were victims of forced sterilization, a practice discussed further in the Spotlight in this section.

https://player.pbs.org/viralplayer/3050048007/

Oregon’s Fairview Training Center remained fully operational (and overcrowded) well into the 1980s, despite advocacy by the oppressed residents, sanctions for mismanagement and abuse of the people it housed, and even a U.S. Department of Justice investigation in 1985. Fairview finally began to downsize, but it stubbornly remained open until 2000. The institution housed 1,500 residents in 1986 and was down to 300 by 1996 (Drummond, 2000). For more information on another Oregon institution, see the Spotlight in this chapter on the Oregon State Hospital.

SPOTLIGHT: Carrie Buck and the Practice of Eugenics

Of the many abuses experienced by people with mental disorders, forced sterilization was one of most harmful and lasting violations against this vulnerable population. The story of Carrie Buck, which can be difficult to read, is an infamous example of this abuse.

The reproductive sterilization movement in the United States took off in the 1890s, aimed at removing certain “unfavorable” characteristics from the gene pool. Interference with and control of reproduction for these reasons is called eugenics. In eugenics, sterilization was used to perpetuate racism, as well as ableism and misogyny, so groups of immigrants, people of color, and the poor—mostly women—were ready targets. People who had been institutionalized due to mental disorders, such as developmental disorders or medical conditions like epilepsy, were deemed “feebleminded” and were easy victims of eugenics programs (Ko, 2016). Eugenics programs aimed at eliminating this disfavored group of people were reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court in the 1927 case of Buck v. Bell.

In the fall of 1923, Carrie Buck (figure 1.10) was a 17-year-old foster child living in the state of Virginia. When Carrie became pregnant (she was raped by another family member), it was decided that the best thing to do was to institutionalize Carrie for being an unwed teenage mother. Carrie’s condition was considered a sign that she was morally delinquent and “feebleminded.” Having been born to a “feebleminded” mother, Carrie’s baby was considered “feebleminded” upon her birth and was eventually adopted by Carrie’s former foster parents. Meanwhile, Carrie was sent to the Virginia State Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded in Lynchburg, where she was reunited with her mother, Emma Buck, who had also been institutionalized (Antonios & Raup, 2012).

Carrie Buck, just 18 years old, was then ordered to be sterilized under Virginia’s 1924 Eugenical Sterilization Act. The order was examined and approved by the Virginia courts and, eventually, by the Supreme Court in Buck v. Bell (1927). The Supreme Court endorsed the sterilization of Carrie Buck and others like her, comparing the procedure to a preventative health measure, like vaccination: “The principle that sustains compulsory vaccination is broad enough to cover cutting the Fallopian tubes.” (Buck v. Bell, 274 U.S. at 208).

While Virginia went on to sterilize at least 8,300 people, most other states, including Oregon, had similar programs. Oregon’s official Board of Eugenics was formed in 1923. It was later renamed the Board of Social Protection, and it remained intact until 1983. As part of its eugenics program, Oregon forcibly sterilized people with mental disorders at its Fairview Training Center, in addition to other targeted groups: people identified as criminals or homosexuals, youth in reform schools, and young girls considered to be promiscuous.

Although eugenics is officially disfavored today, the Buck v. Bell case was never expressly overturned, and the inhumane thinking behind the decision had a far-reaching impact. The Buck v. Bell decision served to empower the eugenics movement in America, leading to the sterilization of an estimated 65,000 Americans with mental disorders from the 1920s up through the 1970s (Ko, 2016). Horrifyingly, the American states’ eugenics programs are said to have inspired early Nazi sterilization programs intended to rid the German population of “feebleminded” people (Jewish Virtual Library, n.d.).

Racial Segregation in Institutions

Given that institutionalization of people with mental disorders took place during a time of widespread racial segregation in America, there were also state hospitals, or sometimes parts of hospitals—such as basements—dedicated to housing Black patients. Although the Civil Rights Act of 1866 required state hospitals to accept Black patients, many completely refused to do so, and where they were admitted, they were segregated from white patients (Swenson, 2017). Virginia’s Central Lunatic Asylum for the Colored Insane, later known as Central State Hospital, was filled in the late 1800s with Black patients housed in primitive and abusive conditions (figure 1.11). All of the women in the facility were guarded by men, based on the thinking that the women needed guards with enough strength to properly control them. Many of the Central State Hospital residents had been deemed mentally ill and fit for institutionalization based on nothing more than accusations by racist whites unhappy with the free status of formerly enslaved people. Some Black residents were declared insane based on their simple desire to be free (Brumfield, 2021). Indeed, during the period of slavery, Black people had routinely been found mentally ill simply for desiring or attempting to escape enslavement (Swenson, 2017).

Patients in early American psychiatric institutions rarely received humane care or treatment for mental illness or whatever disorder had led to their confinement, but this failure was especially pronounced for Black patients. These patients endured particularly dehumanizing treatment based on their race. In records from the Central State Hospital, detailed notes about patients were almost always summaries of their “usefulness”—that is, their ability to work. Formerly enslaved people both in and out of institutions were considered valuable only to the extent they could be part of a planned cheap labor force in the post-slavery era (Swenson, 2017).

Treatment of Mental Disorders in the 1900s

During the mid-1900s, treatments offered to patients in state hospitals had expanded beyond bloodletting, but these treatments remained in experimental stages. Mentally ill and disabled people in institutions suffered the burden of trial and error. Modern electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which involves passing small electric currents through a patient’s brain, is performed under anesthesia with safeguards in place. ECT creates changes in brain chemistry that have been highly effective in treating challenging conditions such as severe depression (Mayo Clinic, 2018). However, the original version of this treatment, known as electroshock therapy, induced seizures with large amounts of electricity, but without the advancements of modern medicine. The procedure was done without anesthesia or sensitivity to the patient, and it was terrifying and dangerous. A patient described electroshock therapy at the Missouri state hospital in 1957 as a terrible ordeal:

Patients were generally on [electroshock] treatment twice a week. . . . Begging, pleading, crying, and resisting, they were herded into the gymnasium and seated around the edge of the room.

Between them and the shock treatment table was a long row of screens. The table on the other side of the screen held as much terror for most of these patients as the electric chair in the penitentiaries did for criminals. . . . In order to save time, one or more patients were called behind the screen to sit down and take off their shoes while the patient who had just preceded them was still on the table going through the convulsions that shake the body after the electric shock has knocked them unconscious.

One attendant stands at the head of the table to put the rubber heel in their mouth so they won’t chew their tongue during the convulsive stage. On either side of the table stand three other attendants to hold them down . . . (Office of the Secretary of State, Missouri. (n.d.).

Early brain surgeries to treat mental disorders were, likewise, an ill-advised and often devastating approach. Modern brain surgeries are very promising in treating certain conditions, such as severe epilepsy, but the practices and goals in these early days were quite different. A surgery called a lobotomy, for example, where part of a person’s brain was removed with a goal of managing or curing mental illness, was performed on patients up until the 1950s in America (Tracy, 2019).

Rosemary Kennedy, the sister of eventual president John F. Kennedy, was subjected to a lobotomy as a young woman in 1941 (figure 1.12). Rosemary’s father, Joseph Kennedy, ordered the lobotomy when Rosemary was in her early 20s. As a result of the surgery, Rosemary was left seriously disabled (John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, n.d.). It has been speculated that Joseph Kennedy’s request was motivated by Rosemary’s disruptive behavior, which caused the family embarrassment and threatened the political careers of the Kennedy men (Gordon, 2015). Rosemary was influential largely because of the impact her experience had on her powerful and famous family, including her brother John, who became President in 1961, and her sister Eunice Kennedy Shriver, who worked to improve the lives of people with developmental disabilities and founded the Special Olympics in 1968. Rosemary herself was hidden from public view and was cared for in an institution away from even her family for most of her life.

Perhaps the most famous recipient of a lobotomy is a fictional one: Randle McMurphy, the hero of Ken Kesey’s 1962 anti-psychiatry novel, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. The novel, set in an Oregon psychiatric institution, tells the story of patients rebelling against oppressive and abusive treatment. In Kesey’s story, McMurphy fakes mental illness to avoid criminal responsibility; he ends up both inspiring his fellow hospital residents and suffering along with them. Kesey’s book came out as civil rights activists were questioning all aspects of establishment and authority in America—including state hospitals. The book and its 1975 film adaptation, which also depicted a horrifying view of ECT as more torture than treatment, were award-winning pieces of art, and they certainly left a broad group of Americans questioning the value and ethics of psychiatric hospitalization and treatment (Moffic, 2014).

Licenses and Attributions for Mental Disorders in Modern Times: The Rise of Institutional Treatment

Open Content, Original

“Mental Disorders in Modern Times” by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Open Content, Shared Previously

“SPOTLIGHT: Carrie Buck and the Practice of Eugenics” by Monica McKirdy and revised and expanded by Anne Nichol is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

The subsection “Creation of State Hospitals” within “Mental Disorders in Modern Times” is adapted from:

- “Mental Health Treatment: Past and Present” by R. M. Spielman, W. J. Jenkins, and M.D. Lovett, Psychology 2e, Openstax which is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

- “History of Mental Illness” by Ingrid G. Farreras, Noba Textbook Series, Psychology, which is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

Modifications by Anne Nichol, licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0, include substantially expanding and rewriting.

Figure 1.7. “Benjamin Rush’s Tranquilizing Chair” by National Library of Medicine is in the public domain.

Figure 1.8. “U.S. Library of Congress DIX, DOROTHEA LYNDE” by U.S. Library of Congress is in the public domain.

Figure 1.10. “Carrie and Emma Buck at the Virginia Colony for Epileptics and Feebleminded” by A.H. Estabrook before the Buck v. Bell trial in Virginia, is in the public domain.

Figure 1.11. Photograph of Black women in the Central State Hospital is in the public domain.

All Rights Reserved Content

Figure 1.9. Eugenics: In the Shadow of Fairview [clip of Season 15 Episode 1] by OPB is included under fair use.

Figure 1.12. Photograph of Rosemary Kennedy, photographer unknown, is part of the Kennedy Family Photograph Collection used at nps.gov and included under fair use.